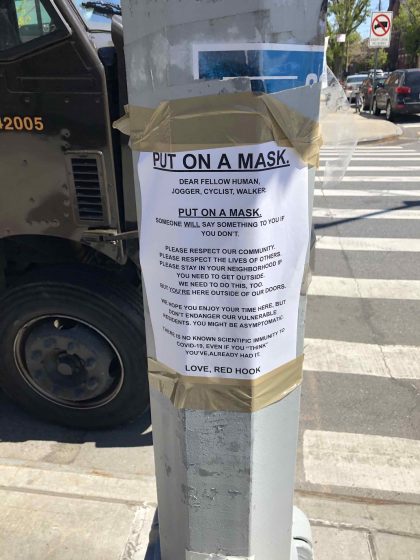

We started to settle into our “new normal”, with the pace of our journal entries significantly slowing down. Social distancing didn’t feel as novel any more, we weren’t noticing the shifts and changes as much. Or perhaps we were worn down with mental fatigue and journaling didn’t feel therapeutic, it felt frankly depressing. Even the daily, spontaneous 7pm cheer for frontline workers from city rooftops and apartment windows had faded over time in our corners of the city. At the same time, our worlds were also expanding — ever so slightly. As we went from a complete shutdown through the stages of reopening, we found new and creative ways to socialize: in parks, on rooftops, with outdoor dining in the streets across the city. All of this had to be navigated through our personal understandings and comfort with the risk involved in doing so. We were all trying to think like amateur epidemiologists.

Starting in June we began to conduct interviews with local civic environmental stewardship groups and public agency natural resource managers at city, state, and federal levels as part of our STEW-MAP research effort, to understand how they were adapting to and impacted by COVID-19. All of this trained our eye in new ways to attune to the ongoing changes around us — the radical and subtle shifts in how we are relating to our neighbors and the nearby nature around us. As such, this essay draws on both our personal observations of our neighborhoods as well as some of the emerging themes from interviews with dozens of civic stewards and public land managers. We found that civic groups and public agencies are stewarding nature so that it is providing some of our most basic needs during the pandemic — food, respite, and safety.

FOOD

As the pandemic unfolded and many lost their jobs, struggled to make ends meet, and needed to find a way to pay rent, food insecurity emerged as a growing problem. Recent data from Feeding America suggests that the pandemic could force an additional 17 million Americans into food insecurity, bringing totals from the current 37 million food insecure to a projected 54 million food insecure people nationwide. Mutual aid groups focused on purchasing and distributing groceries to neighbors in need, and the community fridge movement grew. While these grassroots efforts multiplied, many civic environmental stewardship groups asked themselves how they could flex and adapt their missions and programs in order to help.

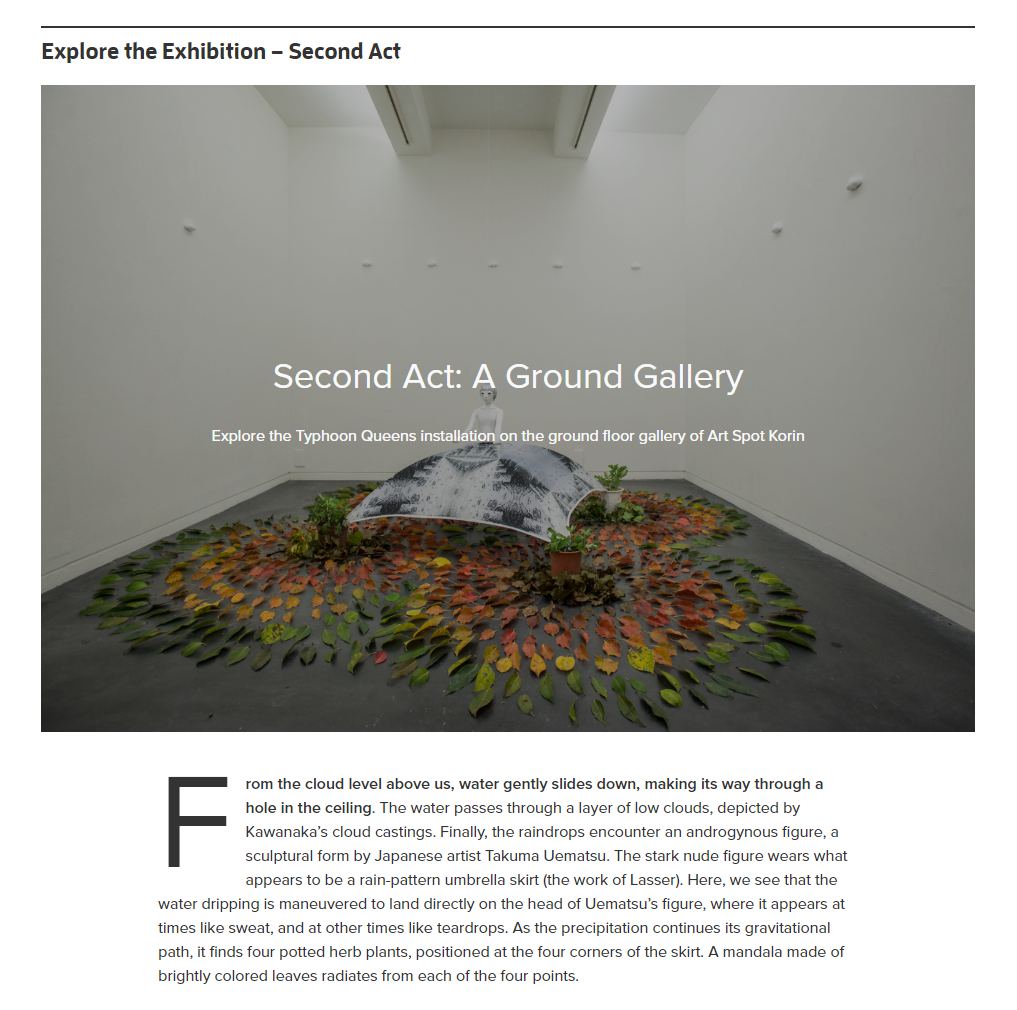

RIGHT: Food distribution project at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden Children’s Garden. Photo: Lindsay Campbell

Some of these stewardship groups already worked in urban agriculture and saw an opportunity to redistribute the produce they grew to community members that need it most. One group, an education program that installs and builds curricula around hydroponic rooftop farms in school buildings, was already working with community partners to distribute produce grown in the classrooms. They use their gardens to teach lessons about the food chain, including food access. COVID has further revealed food insecurity within school communities as well, and moving forward they hope to redistribute the produce to school families in need. Another stewardship group that manages an on-site demonstration garden for school groups recently started distributing their produce to community partners. Prior to COVID, the produce they grew would be sent home with students or employees, but staff realized that the 100lbs of produce they grow each week could have an even bigger impact. Now, they are donating at least 20lbs a week to five different local organizations to subsidize fresh produce.

Many community gardens across the city are well set up to grow and distribute produce, but not all of them have the resources to do so. One citywide organization decided to focus their efforts on a new community farm hub program that supports groups looking to get involved in food production. They have made introductions between civic groups that hadn’t previously partnered, distributed seed packets, and conducted online trainings to help kickstart community farming. A few participating gardens have even collaborated to start local farmer’s markets. Another urban farm partnered with existing organizations and emergent mutual aid networks to purchase and distribute free farm boxes to residents who were struggling as a result of the pandemic. In the early days of lockdown, they called neighbors to identify those who didn’t have enough food to get through the week. At the peak, they were giving out roughly 450 boxes weekly, with pick up locations in multiple spots in the neighborhood and a delivery system for seniors and those unable to pick up in person.

Groups with gardens and farms aren’t the only ones pivoting to address food insecurity. One social weaver who founded a stewardship group to address community needs after Hurricane Sandy used her contact list to start a meal distribution program in the neighborhood back in April. At first, she partnered with a food pantry to deliver ready-to-eat meals to neighbors in need, but they weren’t very popular because they didn’t always match the cultural tastes of her diverse community. Now, she is distributing boxes of groceries that allow community members to prepare their own meals. She described packing up her car multiple times a day and driving around asking people if they’d like some food. She shared a story of one particular instance when she saw a mother and child in need, did a U-turn thinking “just maybe they need something,” and the food she offered was gratefully accepted.

In addition to these and many other efforts by civic groups, the NYC Department of Education gave all NYC public schools students a $420 voucher for food as part of the federal Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer (P-EBT) program. The voucher could only be spent by the bearer and not donated. There was an effort by City Council member Brad Lander and others to encourage those with means to spend the voucher and donate the same amount used to food pantries.

These and many other efforts to address food insecurity have helped sustain many New Yorkers through an unbelievably challenging time. And yet, as people return to work and emergency relief slows, it is becoming evident that not all of these responses are sustainable in the long term. Many of the stewards and activists we spoke to shared visions and dreams of moving away from a charity model of distributing free food, and towards true food sovereignty. What would it look like for vulnerable communities to control their own food system?

TRASH

Throughout shelter-in-place orders and ongoing social distancing rules, parks remained open, accessible, and vital to community health and well-being. While playgrounds, courts, ballfields, and community gardens in NYC were temporarily closed to ensure public health, many of our interviewees steward larger parks that include forested natural areas that provided access for nature recreation and respite throughout the pandemic. Land managers at all levels — federal, state, and local — and civic stewards reflected on how parks, forests, and open spaces were experiencing record levels of use and influxes of visitors. Our interviewees — as well as public health experts, elected officials, and the media — asserted the renewed and vital importance of open green spaces for fresh air, exercise, socialization, and connection to nature during these incredibly difficult times.

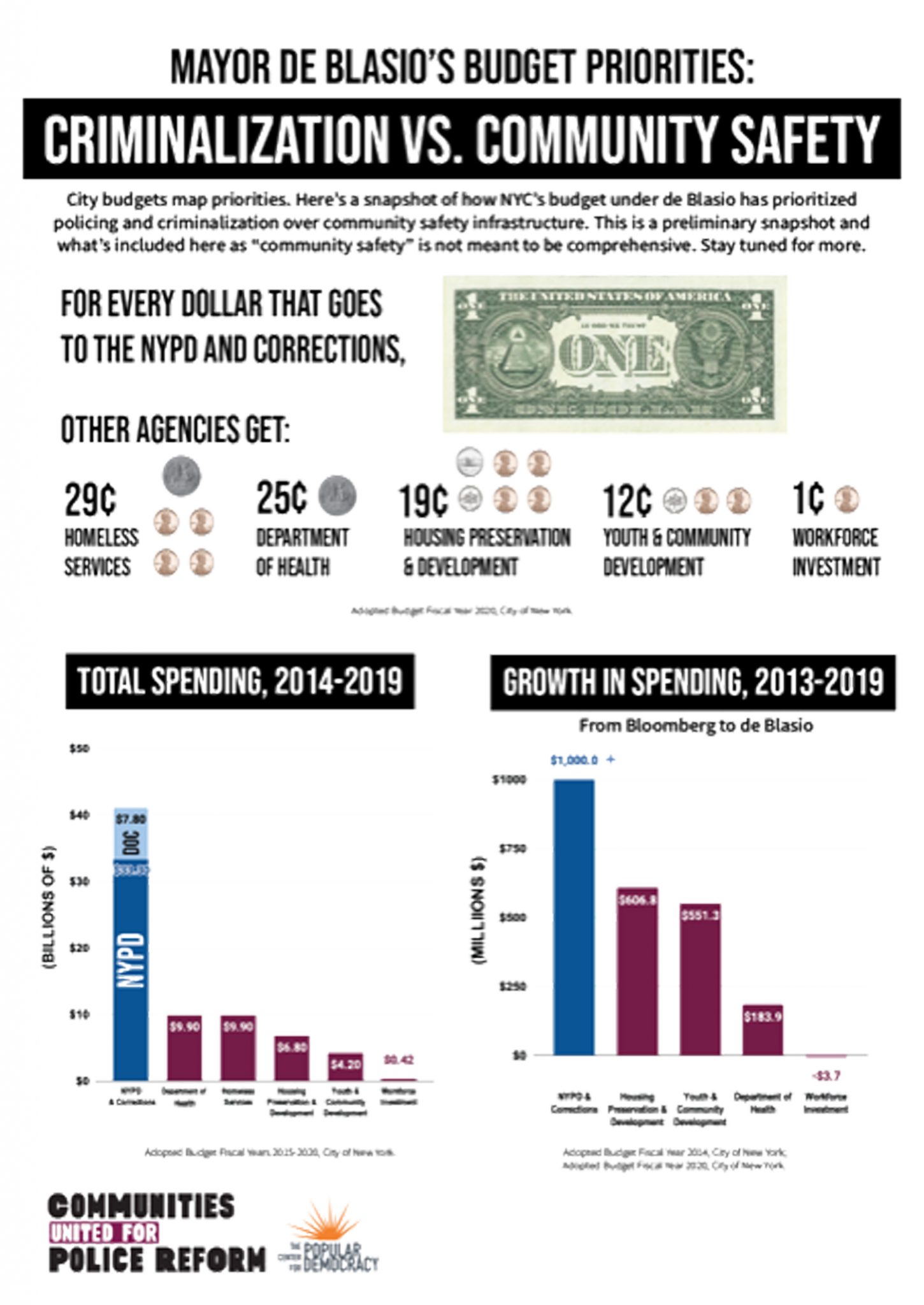

At the same time, with this increase in use, there has been an increase in trash left behind from these visits, including both overflowing garbage cans and litter on the ground. The trash issue is exacerbated by the fact that many parks are operating with cuts to budget and staff. According to New York Times reporting, NYC Parks has received an $84 million budget cut. Additionally, a report by New Yorkers for Parks found that the non-profit organizations that provide maintenance, operations and other services for city-owned land anticipate a 60% decrease in revenue for 2020, which will translate into a loss of 40,000 hours of park maintenance and 110,000 lost hours of horticultural care city-wide. Public land managers are highly aware of these visitor impacts — and are redoubling their efforts to stay apace with trash pickup and other crucial maintenance tasks. Many public land managers expressed disappointment that at the time when there is such an influx of new visitors, they are struggling to provide the level or service or high quality experience. New visitation has also resulted in a new influx of volunteers. Public land managers are working to focus this energy on litter-pickup rather than horticultural activities.

Public agencies are not alone in responding to this challenge; individuals and civic groups are also involved in clean-ups and trash prevention. Some excerpts from Lindsay’s journal track individual and community-organized cleanups around Brooklyn:

8 May 2020

I don’t usually like to go to the beach at Valentino Pier after a rainy day (because of all the trash on the beach), but my daughter was asking repeatedly to go. I saw my neighbor and his toddler with a full bag of trash and a trash picker. He had completely cleaned the beach of all its debris. He is the primary caretaker of his toddler, as he lost his job during COVID. On the walk back, I saw him across the street continuing to pick up trash — so not just the beach, but strewn gloves and masks from the sidewalk.

10 August 2020

On Saturday morning, my family and I went to Prospect Park for the first time since the lockdown and met up with friends and their dog for a distanced hello. I was really surprised by the amount of trash — not just cans overflowing, but cups and cans and things just loose on the ground under trees. It was 11am and the park was already quite full and we had to walk a ways to find a shady, safely distanced spot. Then, what should I see, but a parent and 2 kids with trash pickers and bags going around picking up trash. And they weren’t the last — I saw about 6-8 people doing the same thing throughout the park. Call it “COVID plogging,” but people are definitely helping to maintain the “loved to death park.”

A neighborhood Red Hook mom I know organized a trash pickup on Valentino Pier at the beach for this Monday, 10am. The beach seems like a special issue though, because most of the trash is tidal, not litter.

27 August 2020

A South Brooklyn mom is organizing folks to adopt their blocks to pick up trash — started a google map — and following a model she read about from the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Reminds me of the way that the rainbow scavenger hunt map started and went viral.

RIGHT: Volunteer participant at a Monday morning community cleanup with Prospect Park Alliance. Photo courtesy of Janeen Potts.

These community-led clean-up efforts are being encouraged and nurtured by public agencies (e.g. community cleanup tool lending from the Department of Sanitation) and elected officials (e.g. Bronx Borough President Reuben Diaz’s “Meaningful Mondays”). From our interviews, we found that civic stewardship groups are helping to address this gap by creating campaigns encouraging users to pick up their trash and some are even handing out trash bags as visitors enter parks. Park conservancies and other partners to the city are sounding the alarm about park budget cuts and making efforts to restore budget for these crucial services in future budget years. Park advocates have formed coalitions and are calling for city budget increases to maintain parks as well as writing opinion pieces calling for the creation of new parks in areas where they are most needed, to address disparities in park access that have been magnified under coronavirus.

STORMS

The impacts of the COVID-19 crisis intersect with pre-existing inequalities and vulnerabilities across our population. One horrifying, but incredibly plausible scenario that city officials had to prepare for was the possibility of pandemic, heat wave, and hurricane co-occurring.

As tropical storm Isaias barreled toward the city, residents — particularly those in coastal communities–found themselves bracing for impact. Fortunately, New Yorkers were spared from experiencing flooding because of its trajectory, timing, and alignment with the tides — if these had been different, coastal neighborhoods could have experienced the sort of storm surge that occurred during Sandy. However, the storm’s high winds had an incredible impact on the city’s urban forest — leading to over 3,300 downed trees and over 32,000 tree-related public service requests sent into 311, the city’s customer service line, in five days (data provided by NYC Parks as of 28 August 2020). This is the largest number of public service requests since storm event record keeping began in 1997 and more than a third of what is typically received in a year. These downed trees damaged property and created power outages, some of which stretched on for a week, during summer daytime heat in the 90s. Residents in New Jersey, Westchester County, and Connecticut experienced extensive power outages as well. New York City Parks responded by mobilizing its workforce to respond rapidly in real time to these resident calls, to ensure that streets and sidewalks were safely cleared.

We are reminded that in addition to the first responders who stabilize life and property after a disaster, those we call “green responders” work to restore communities and landscapes by caring for the natural world. These green responders include both public land managers and civic stewards, and disturbances can be acute (storm, tornado, hurricane) or more slow moving (food insecurity, economic disinvestment) — and their actions are a crucial part of long-term recovery and preparedness cycles.

The residents of the waterfront community of Red Hook, Brooklyn — particularly low income, often people of color living in NYCHA’s public housing–understand firsthand what it is to experience multiple vulnerabilities. In 2013, Hurricane Sandy devastated the neighborhood with flooding, power outages, and sustained damages to infrastructure and the built environment. After seven years, major retrofits to the NYCHA buildings and grounds are finally being made this summer to improve flood resilience. Yet, according to interviews with neighborhood activists, this construction is occurring at a large-scale across the entire campus all at once — cutting off residents from vitally needed local open spaces during the pandemic, removing over 450 mature trees, and leaving piles of construction debris and soil uncovered and exposed to air. These unintended side effects of much-needed capital improvements reflect the complex realities of and dire need for retrofitting our infrastructure and landscapes to be resilient to multiple disturbances, while working closely with and listening to local residents. On several instances, water mains had to be shut off to allow for construction, which simultaneously cut off access to fresh water for drinking and hand washing for residents. Local activists, nonprofits, and mutual aid groups stepped in to ensure that water was provided to residents — along with the already existing food distributions that were occurring. Going further, they organized advocacy efforts, including a public rally on 28 July, to target elected officials and the media to ensure that residents’ concerns were heard and addressed (see also #LetRedHookBreathe and #FullyFundRedHookHouses). Local leaders continue to educate the public, the media, and elected officials on the ways in which threats like climate change intersect with social justice and inequality to affect people’s lived experiences, particularly for public housing residents (e.g. see upcoming webinar).

We are cognizant that we are writing these reflections on storms and COVID-19 from the Eastern United States, while huge portions of the west coast are ablaze with unprecedented wildfires. How can we best protect, prepare, and adapt our communities–particularly the most vulnerable among us — to sustain in the context of extreme weather and climate change occurring alongside a public health crisis and massive social upheavals? How can caring for the land–as both a profession and as an avocation — play a part in making us more resilient?

POWER OF PUBLIC LANDS

Reflecting back on this summer, it has been a stark reminder of what food, shelter, and safety means to different groups of people. For some it is the continuance of good food while supporting one’s local restaurant and for others it is the basic need for food. Safety may mean public recreation free from debris and for others it may be access to clean water or safe streets. Shelter for so many this summer has also been about finding a respite in our public lands as a walk in the woods or neighborhood park can offer relief from this time of stress and uncertainty.

Of course, our public lands — wherever they may be — do more than offer temporary relief. As we enter these spaces, we are in the company of others — past, present, and future humans. In these spaces, we are, perhaps, reminded of a shared humanity and of natural forces that are great and alive, redemptive and destructive. As summer comes to a close, we prepare again for a season like none other. Many teachers will be in the classroom while their students are at home, on-line or struggling just to stay connected. Families and friends will find new ways to mark the fall and winter holidays and remembrances that often accompany the year’s end. And we know that public lands will continue to play an abiding role in our daily lives, as public space has always been a stage for the performance of everyday life. An excerpt from Erika’s journal:

1 September

I was reluctant to go to the park this evening with so much weighing on my mind. What would school be like this year for my kids? Will they fall behind? How will they stay safe but still be with their friends? Will they still feel part of a community? Eventually, I grabbed my mask, a blanket and a few snacks to share for an impromptu, socially-distanced picnic in Prospect Park. There I joined other mothers, fathers, and friends as we talked about our hopes and fears for the coming academic year. We shared stories of the summer that made us laugh. And we shared moments where one of us might have cried out if our kids hadn’t been within hearing distance. Our talk went on as the moon rose over the trees. A man on a bike approached our group. He stopped and shared a song with us. Soon we were encompassed by the music of Earth, Wind and Fire’s, No. 1 hit from the 1970s, September. Suddenly, we forgot our train of thought and leapt to our feet to dance under the moonlight. Wild, crazy dancing. For a moment, our children stared back at us in mild shock. Eventually, everyone joined the needed revelry on this first night of September.

Do you remember the 21st night of September?

Love was changing the minds of pretenders

While chasing the clouds awayOur hearts were ringing

In the key that our souls were singing

As we danced in the night

Remember how the stars stole the night awayHey hey hey, say do you remember?

Dancing in September

Never was a cloudy day— Excerpt from “September” by Earth, Wind and Fire

Lindsay Campbell, Michelle Johnson, Laura Landau, Sophie Plitt, and Erika Svendsen

New York

about the writer

Michelle Johnson

Michelle Johnson is a research ecologist with the USDA Forest Service at the NYC Urban Field Station.

about the writer

Laura Landau

Laura is currently pursuing a PhD in geography at Rutgers University. Her research focuses on the civic groups that care for the local environment, and on the potential for urban environmental stewardship to strengthen communities and make them more resilient to disaster and disturbance.

about the writer

Sophie Plitt

Sophie Plitt is National Partnership Manager the the Natural Areas Conservancy. Sophie works to engage national partners in a workshop to improve the management of urban forested natural areas.

about the writer

Erika Svendsen

Dr. Erika Svendsen is a social scientist with the U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station and is based in New York City. Erika studies environmental stewardship and issues related to hybrid governance, collective resilience and human well-being.

1 Comment

Join our conversation