about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David's dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to "fall back on". So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

Resilience.

Resilient.

It is is the word of the decade.

As sustainability was before it.

A challenge with both words, directed at us, and especially as they relate to specific ideas and actions, is this. While they exist so well in the realm of metaphor, they are more difficult in reality. The same can be said for “livability” and “justice”. “Sustainability”.

But let’s embrace thinking in a different way.

Let’s strike out in possibly new metaphorical directions.

In this roundtable, we invited 18 artists and designers of various types to respond—in words, images, or other works—to the word.

Resilience.

This Roundtable is a co-production with Arts Everywhere.

about the writer

Juan Carlos Arroyo

Animation Specialist and Master of Fine Arts of the National University of Colombia. Juan Carlos Arroyo is working on a master research project called "CRISIS PROCESSES AND RESISTANCE: The historical context with a focus on the images and humane care of the Hospital San Juan de Dios Bogotá 2002 - 2014 ".

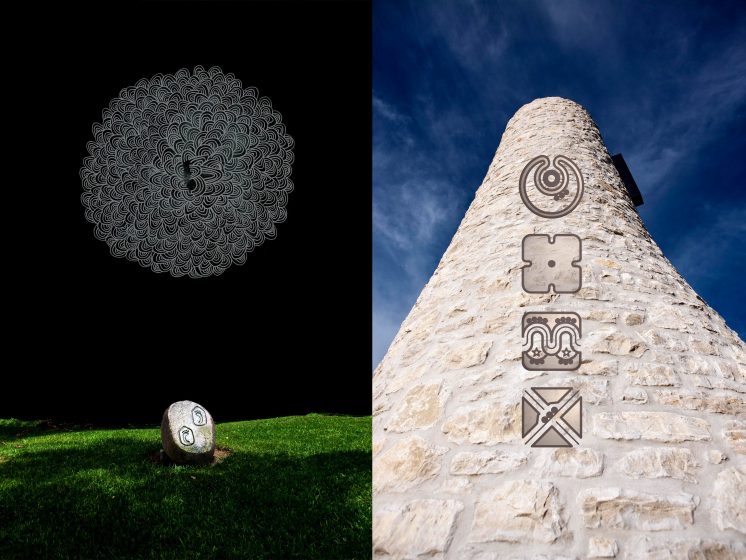

Juan Carlos Arroyo

La Imagen y el cuidado humano // Image and Human Care

(English version follows here.)

El Hospital San Juan de Dios de la ciudad de Bogotá fue cerrado aproximadamente en el año 1999, más de 3.600 trabajadores perdieron sus puestos fuentes de ingreso. Algunos de ellos hoy en día persisten en la resistencia al cierre y desaparición del hospital más antiguo de Sudamérica.

La acción de diversos factores sociales, políticos, económicos y culturales llevó a este hospital a una situación recurrente de crisis y posterior cierre. Este es un caso entre muchos otros; desde la implementación de la Ley 100 de 1993 la salud pública en Colombia ha cambiado significativamente, no es la causa de todos los males, pero si resultó un detonante de síntomas a una crisis organizativa y financiera que venía de tiempo atrás.

Pero los hospitales abren y cierran, así como las personas se enferman y recuperan su salud. No es difícil encontrar constantes contradicciones y opiniones opuestas sobre el estado de la salud en Colombia, así, como sobre la propia salud humana. Si seguimos la pista a la crisis hospitalaria en Colombia a través de los medios de comunicación y los debates públicos, veremos que hospitales un día colapsan, y al cabo de años estos resurgen, entonces ¿por qué se persiste en la resistencia al cierre?

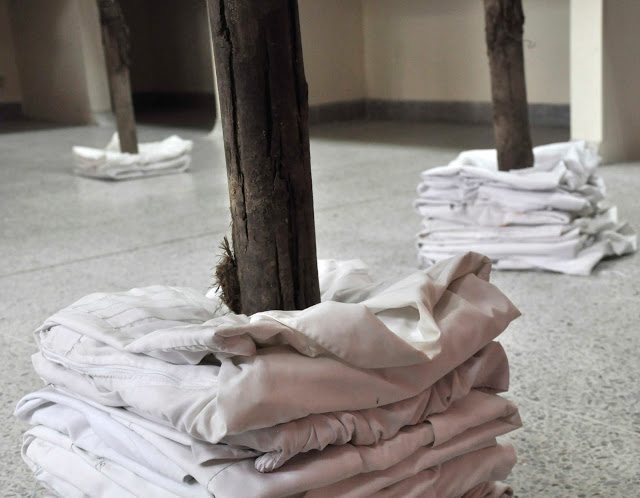

La imagen/síntoma de un hospital que se deteriora y cierra es una imagen poderosa. Ha motivado la realización de varios trabajos artísticos, la poética en ellos nos transmite a través de la imagen las reflexiones y preguntas abiertas sobre la importancia de un hospital como el lugar del cuidado humano.

Individuales como Estado de coma de María Elvira Escallón, las fotografía de Nicolas Van Hemelryck y también otras intervenciones colectivas como el evento TIMEBAG Bogotá 2015 intervención en el HSJD por parte de 9 artistas de nacionales, bajo la curaduría de Gabriel Mario Vélez. Algunos ejemplos:

Cuando un lugar de cuidado humano desaparece, cuando las personas que trabajaron allí salvando vida fueron ignorados, algo malo que ha ocurrido con nuestra sociedad, es como un erupción en la piel, algo que a simple vista parece no estar bien, pero, ¿qué es lo que pasa allí?, ¿los procesos de resistencia al cierre son manifestaciones de un cambio profundo en la concepción de la salud?

Lo que sobrevive en el acto de resistencia es un ideal de cuidado humano, una concepción de salud humanitaria y desinteresada que parece extinguirse con el avance de modelos económicos.

* * * * *

The San Juan de Dios Hospital of Bogota was closed around 1999, and more than 3,600 workers lost their jobs and sources of income. Today, some of them persist in their resistance to the closure and disappearance of South America’s oldest hospital.

Various social, political, economic, and cultural factors led the hospital into a recurring crisis and finally closure. This is one case among many. Since the implementation of Law 100 in 1993, public health in Colombia has changed significantly. The law is not the cause of the crisis, but it triggered the symptoms of the organizational and financial crisis that started long ago.

But hospitals open and close, and people get sick and recover their health. It is not hard to find constant contradictions and opposing views on the state of health in Colombia, as well as on human health itself. If we follow the trail leading to the hospital crisis in Colombia in the media and public debates, we see that hospitals collapse one day, and after years they resurface. Why, then, do we persist in resisting their closure?

Images of a hospital that is closed and deteriorating are powerful and have motivated the realization of several artworks. The poetic conveys the buildings through image reflections and raises questions about the importance of a hospital as the place of human care. Examples include Coma State (En estado de coma) by Maria Elvira Escallón, the photographs of Nicolas Van Hemelryck, and other collective interventions such as TIMEBAG Bogotá 2015 HSJD by nine national artists, curated by Gabriel Mario Velez. (For examples, see the photos in the Spanish version above.)

When a place of human care disappears, and when people who worked there saving lives are ignored, something bad has happened to our society, like a rash that at first glance does not seem right, even though it is there. The resistance to closure processes is a protest to a profound change in the conception of health.

What survives in these acts of resistance is an ideal of human care, a concept of health and selfless humanitarianism that seems extinguished with the progress of economic models.

about the writer

Katrine Claassens

Katrine Claassens' paintings reflect her interest in climate change, urban ecology, and internet memes. She also works as a science, policy and climate change communicator for universities, think tanks, and governments in South Africa and Canada.

Katrine Claassens

“You are so brave and quiet I forget you are suffering” —Ernest Hemingway, A Farewell to Arms (1929)

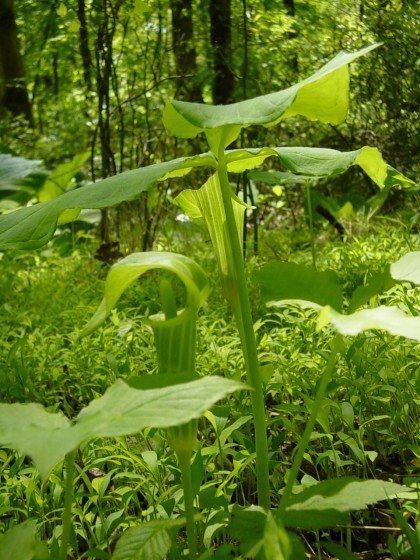

Resilience is a word often understood in terms of strength—something is resilient because it is strong. In the Anthropocene, however, we would do well to understand resilience in terms of fragility as well. One of the more troubling arguments I have heard in relation to resilience is this: that nature will find a way to survive no matter what we subject Earth (or ourselves) to. For me the issue at hand is not just whether nature will survive the 6th extinction that we are currently living through, but rather whether we can afford to be so complacent about the increasingly diminished form it is taking. Be certain, there will be no clear ‘winners’ on our current ecological trajectory.

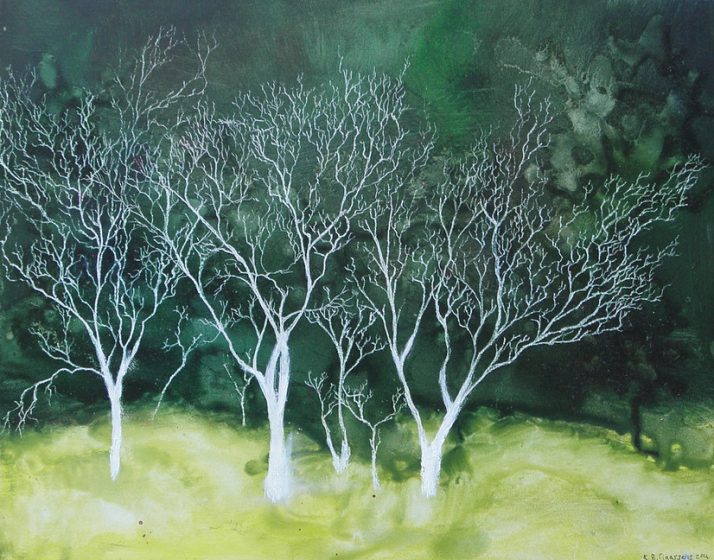

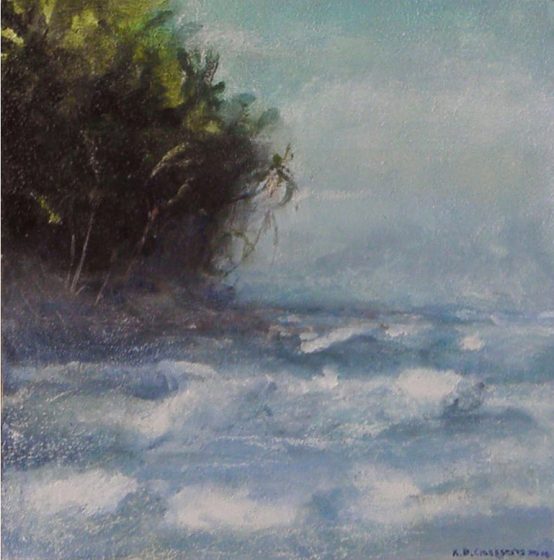

Here I present a series of paintings that bear witness to the novel ecologies of the Anthropocene. These paintings are dedicated to landscapes that embody the duality of vulnerability and strength inherent in resilience for both humans and the natural world. Three of these paintings, Edith Stephens I, II and III, address a damaged, watery realm on the outskirts of Cape Town, a place I find particularly pertinent to the topic of resilience.

In the 1940s, Edith Stephens, a botanist at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, found that the diverse flora and (small) fauna of the wetlands outside the city were under threat from ongoing habit loss and degradation due to urban and agricultural expansion. Her conservation efforts to preserve something of the wetlands eventually resulted in a nature reserve being established.

Now triangled between two busy roads and a densely populated informal settlement, the Edith Stephens Wetland Park is in an area where both humans and nature are subjected to severe stresses, trauma, and fragmentation. The park is a windswept place, heavy and damp with ecological and social unease: it is not only a vestige of threatened plants found nowhere else in the world, but also a contested open area adjacent to densely packed shacks, in an age when the wisdom of conservation is questioned.

Edith Stephens’ nature reserve has been found to be one of the few homes to an exceedingly rare plant, Isoetes capensis, a small, fern-like ‘living fossil,’ which has remained almost unchanged for 200 million years. That it has survived since the Carboniferous era tells us that it must be incredibly resilient, but does this mean anything in the Anthropocene, where it is now finally facing extinction?

Is resilience itself endangered? We have yet to see whether this may be the case, but our high expectations of resilience from nature (and, indeed, people, too) may be dangerous.

about the writer

David Brooks

David Brooks lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. Recent projects and exhibitions include Pond House Pond, Mildred’s Lane Historical Society, Beach Lake, Pennsylvania (2012); Galerie fur Landschaftskunst, Hamburg (2012); Notes on Structure, American Contemporary, New York (2012).

David Brooks

To sincerely give consideration to the idea of resilience, in a culturally inclusive way, it is the notion of adaptability that floats to the top and becomes the road map to understanding. By adaptability, I don’t mean in evolutionary terms—through natural selection and sexual selection. Rather, I’m more concerned with an adaptability of consciousness—something more immediately within our control. I mean the ability for us to collectively use our evolutionarily gained faculties of reason, synthesized with the concerns of our hearts, synthesized with our creative intellects, and as expressed through our experiential acumen. They all work in unison.

With that we’d formulate a much-needed alternative picture of the biosphere, our place within it, and our future cohabitation. “Resilience” connotes an antidote to the cultural and economic conditioning of global capitalism. That said, it must be done collectivity, which is momentarily politically and culturally impossible. Which is the real drag. So let me start with the individual as opposed to the collective.

Though it may sound a bit silly, and though I am on the mature side of my life span, I still look to my youth—which I spent skateboarding day in and day out—as a role model for this notion of adaptability. Let me explain: skateboarding has really shaped the way I see the urban environment because it’s a perfect amalgamation of urban planning, athleticism, and creative articulation. It’s an unconventional way of getting to know the built environment. Skateboarders move through the city in a similar manner as the Situationists International or the flâneur wandered their cities—sparking and reinvigorating wonder in the pedestrian elements of their conforming environments, like a wall, a bench, or a curb. In the end, it’s about constant adaptation. One must, in the fraction of a second, consider: “How can I use that curb now? How can I use that bench? I’m not going to sit on it, I’m going to slide it and grind it. How can I use that railing? What about the way that railing meets the curb and meets the bench?” There is an entire set of creative adaptations that ensue—which is a radically different way of seeing the urban environment. In skateboarding, you have to embody a fluidity and adapt to flux constantly, instantaneously.

What this example illustrates for me is that to embrace a true sense of resilience is to actually adapt to new understandings of what one’s environment is, and our place within it. But this is a very old story. We don’t have to look far or invent a new story. In fact, it is a story that dates back to biblical times. We have this example in the story of Jonah. When Jonah looked up, after the great storm at sea, he was enveloped within what seemed a coarse, wet cave. Being thrashed about in this cave, Jonah became an object contained in an environment. As the story is told in the Book of Jonah, that environment was actually an object, a whale—for which Jonah was merely a detail of the contents of its mouth (a detail from god). For Jonah, the whale was an environment. For the whale, Jonah was a detail of its mouth, an object. Here detail, object and environment are not only indistinguishable, but merely a matter of perspective. Therefore, the predicament that Jonah finds himself in is that of a detail, that of an object, and that of an environment; all three of which work together monolithically to form the symbolic gesture of divine will through varying relations to the physical and individual body of Jonah. In this narrative, the occupant’s body is the common denominator within fluctuating perspectives and therefore the physical, psychological, and symbolic liaison between consciousness and the collective palpable landscape.

To adopt and therefore adapt a new understanding of our environments, we must think of the whale in the entirety of its being, as a detail (a detail of ocean abyss), and as an object (an object in terms of its body containing mass and mobility), and as an environment (it was indeed an environment for the intrepid Jonah, trapped inside of the whaleʼs mouth), and as a landscape (Jonah could certainly perceive the mouth of the whale as an environment, but the entirety of the whaleʼs body was not in view of Jonahʼs singular perceptual capacity, and therefore existed as a larger landscape that he had to imagine). Once we are able to understand the whale as all of the above, we are able to employ a multitude of empathies toward it simultaneously:

- The whale as a cog [a detail] in a larger system allows us to empathize with it just as we are citizens of a larger society—one of many denizens of a community.

- The whale as a discrete organism [an object] allows us to empathize with it as another being—man-to-man, mammal-to-mammal, being-to-being.

- The whale as an environment allows us to empathize with it as we might care for and tend to a garden of our domicile.

- The whale as a landscape allows us to empathize with it the way we embrace an awe-inspiring vista or how we might explore the caves of an alpine terrain.

This is our moment of succinct adaptation, as manifested through consciousness and our resulting behavior. Within this, a true sense of resilience might be formed.

about the writer

Rebecca Chesney

Rebecca Chesney is a visual artist whose work is concerned with the relationship between humans and nature and how we perceive, romanticize, and translate the landscape.

Rebecca Chesney

Preston to Mumbai (and back)

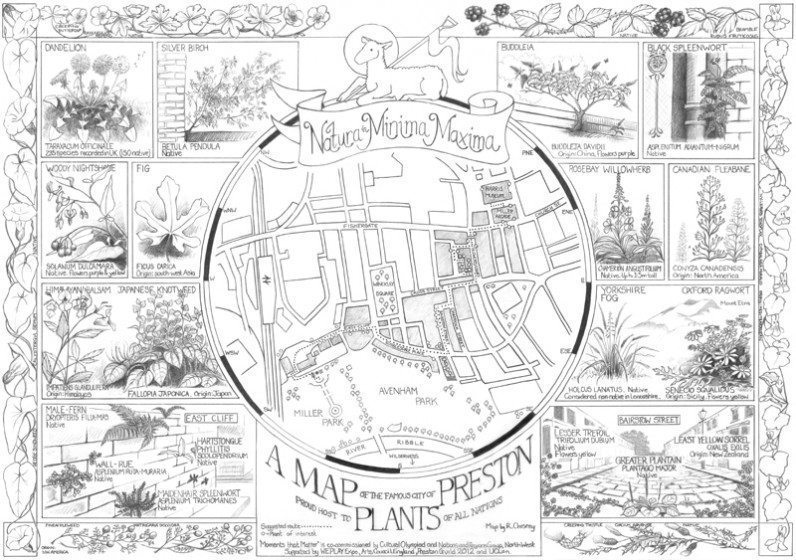

My work as a visual artist is concerned with the relationship between humans and nature: how we perceive, romanticize, and translate the landscape, and how politics, ownership, management, and commercial value all influence our surroundings.

I live in Preston in the U.K. and observing nature within the city has inevitably fed into my work and influenced my ideas. With the urban environment constantly changing, through periods of expansion and development, or recession, decline, and neglect I’ve become attracted to noting the resilience of some species.

In 2006, I conducted surveys in Preston to try and discover all the ‘weed’ species in the city (only species that were unplanned and not deliberately planted on landscaped areas were included in the count). I documented over 50 species in gaps in the pavement, gutters, rooftops, chimneys and on small plots of derelict land. The list includes native, archaeophyte, and neophyte species.

Some can be described as resilient, others as opportunistic invaders, but they’re all surviving in what is seen as an unnatural habitat. Thriving along damp walls and beside leaky drainpipes were some wonderful examples of native ferns: Black Spleenwort, Maidenhair Spleenwort, Wall-Rue, Hartstongue and Male Fern, for example.

Given that Preston is included in the Doomsday Book of 1086, the earliest surviving public record of the land held by William the Conqueror, it is intriguing to wonder if these species have been here since before that time, and how they have adapted to the challenges posed by an ever changing ‘habitat’.

Expanding the project further brought the publication, in 2012, of Natura in Minima Maxima: A Map of the Famous City of Preston, Proud Host to Plants of All Nations. I have continued to record plants in Preston; this hand drawn map reveals some of the 70 species documented since the project started in 2006.

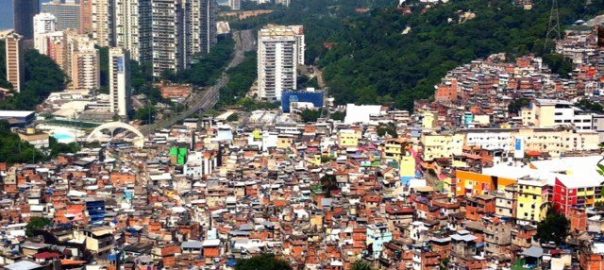

It was while on a Gasworks International Fellowship in Mumbai in 2013, where I was researching the relationship between humans and nature in and around the Sanjay Gandhi National Park, that I was confronted with a situation where both humans and nature are competing for the same space and where each is surviving because of their resilience in the face of continual pressure.

The park, 104km2 of native southern moist deciduous forest, is home to many rare species of plant and animals, including leopards. However, it is almost entirely surrounded by a massive urban population of approximately 20,000 people per km2 (it has been estimated that the population in Mumbai’s metropolitan area in 2013 was more than 20.5 million). During the 1990s, the High Court in Mumbai ruled that, because of the intense pressure on the ecology of the Park from the ever increasing population, all humans should be evicted from the Park. It was estimated that nearly 460,000 people lived in the Park by the mid-90s, but this number included both tribal villagers who had lived in the Park for generations and thousands of illegal encroachers living in self-made shanties.

The problems and conflict triggered from this ruling still resonate today. The land is subject to environmental, political, commercial, and humanitarian issues involving the interests of local authorities, environmentalists, politicians, builders, and land mafia, as well as the thousands of people who still live within the Park boundary.

Relying on the Park for shelter, fuel, and food, the illegal encroachers are some of the poorest in society, with few or no rights, making them very vulnerable. And it’s the plentiful stray dogs associated with these human settlements that have become easy prey for leopards, constituting almost 70 percent of their diet. However, there have been attacks on people living in and around the Park boundary, causing terrible injuries and a number of deaths. Living under the threat of attack from leopards and the threat of eviction from their homes, these communities reveal a resilience and determination to remain. But the authorities in Mumbai are equally determined to protect the wildlife of the Park from the pressure of creeping development, knowing that this unique and incredible habitat could be lost forever if action is not taken.

Living on the boundary of the Park during my stay in Mumbai taught me how complex the situation is—it is not a place of simple, black and white contrasts, but a complicated tapestry intricately woven. Bringing this incredible experience back to the city where I live has given me a new perspective from which to view my surroundings and to consider that, if a balance is to be found where humans and wildlife coexist, we must acknowledge how each situation and circumstance demands a different solution.

about the writer

Emilio Fantin

Emilio Fantin is an artist working in Italy on multidisciplinary research. He teaches at the Politecnico, Architecture, University of Milan, and acts as coordinator of the “Osservatorio Public Art”.

Emilio Fantin

The term resilience suggests a spirit of adaptation, the ability to solve problems, a rebound. As a strategy to improve a problem, resilience transforms the deteriorated situation by holding to it.

To me, revolution suggests an image of utopia, pureness and sacrifice, the drive towards a new world. I see revolution as a primary color, red. It has an impetuous movement, like a red river that becomes a stormy sea. Revolution attacks and destroys the opponent. It dictates a new winner by a clear cut. This is a great strength and a great weakness.

“A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another.”

—Mao Tse-Tung

Resilience drives us to the realm of adaptation. It speaks of transformation and not destruction. I imagine that resilience has a shade of Terra di Siena (Sienna), a complementary color. I used to paint with it in order to give different nuances. Terra di Siena has a less solid quality than red because it is more adaptable. Resilience is the flow of the river that does not converge into a sea. It flows into different channels, gathering enough force to overcome obstacles.

Phonetically speaking, in the word revolution, the combination of “r” and “v” sounds sharp and hard. In the word resilience, the combination of “r” and “s” sounds sweet and fluid.

Resilience sounds sensual and maternal, while revolution sounds imperative and manly. Revolution evokes the orbital movement of planets, Father and Sky. Resilience echoes nature, Mother and Earth. In the 60s, we had the sexual revolution; nowadays we have a gender resilience. The metamorphosis of the bodies is an example of a resilient quality. Terms like trans, inter, intra, with, between, refer to a processuality. Resilience leaves the door always open, while revolution is categoric and it stops a cycle. The resilient attitude of changing and transforming is acting in the generative and reproductive functions, which are the essence of feminine.

Resilience is a form of coexistence. It is a process, a form of living, a relation to nature. It drives us toward a profound interest in ecology and politics. From a political perspective, it can be seen as an attitude to resist and to escape power abuse. It is a strategy to escape strong power, slipping through it without making another enemy and creating an equally strong opponent. Resilience fights the enemy by keeping it to the background, but cannot really destroy it. This is a great strength and a great weakness.

But is it possible to find solutions to the problems of the environment without questioning the values of capitalism? This perspective lets us hope for a better future, but exposes us to the danger of slipping into accepting neoliberal principles as given.

“Stop calling me resilient. I’m not resilient. Because every time you say, ‘Oh, they’re resilient,’ you can do something else to me.”

—Tracie Washington, New Orleans-based civil rights attorney, 2010

about the writer

Lloyd Godman

Lloyd Godman is one of a new breed of environmental artists whose work is directly influencing 'green' building design

Lloyd Godman

Resilience: evolution and growth habit in Tillandsias, a bio-model

In terms of plant evolution, Bromeliads, a family of plants from South America, first appeared relatively recently, about 70-50 million years ago.

About the same time as our ancestral forebears, the early apes, evolved on the planet (15 – 30 million years ago), the massive Andes mountain range thrust upward from intense tectonic activity. In the geological upheaval, countless life forms became stranded by high, rocky peaks and deep valleys. Increasingly, each species was exposed to a “rapidly” changing climate. Mostly drier, colder, and hotter. Relatively quickly (over a few million years), species either became locally/permanently extinct or evolved.

More than any, Tillandsias, a genus of Bromeliads, diversified and about 1000 species evolved in an extremely short period. The success of their profound resilience was founded on adaptive evolution, through which they developed and refined a complex series of biological systems and growth habits that spawned a multitude of weird and eccentric plant forms that are often called air plants. One species, Tillandsia tectorum has been recorded growing in conditions of 75°C temperature change in a single day (-20°C to 55°C)

Many evolved a xerophytic habit (needing little water), became epiphytic (growing on trees or other plants), or became saxicolous (attaching to rocks or sheer cliffs). While the roots became a means only of holding the plant firm, their trichome cells (special cells on the leaf) became more efficient and able to absorb all moisture and nutrients from the atmosphere. Some species have grown in areas where no rain has fallen for more than 20 years. As a climatic defence, these silver cells reflect about 93 percent of the radiation from the sun. Tillandsias dispensed with traditional photosynthetic methods and used a CAM cycle (a modification of typical photosynthesis) to biologically store energy from the sun, followed by growing at night, taking in CO2, and releasing oxygen in darkness, thereby reducing transpiration, which would dehydrate other plants grown in a similarly harsh climate.

Working with Tallandsias

Tillandsias are among the amazing Bromeliad plants that from 1996 have become a signature in my work as an ecological artist,(My early work with Bromeliads can be viewed in this book.)

Tillandsia SWARM

In one of my current Bromeliad Projects, Tillandsia SWARM, small mesh cages with selected species of Tillandsia have been placed on varied locations within Melbourne city, with no auxiliary watering system and left to their own biological devices.

Eureka Tower

At the first location for this project, Eureka Tower, plants were initially installed at 4 sites, on levels 92, 91, 65 and 56 in June 2014. This is the tallest building in the world with plants on; papers on the work were recently published in the Tall Building Urban Habitat Council Journal and also the Green Building Council Journal.

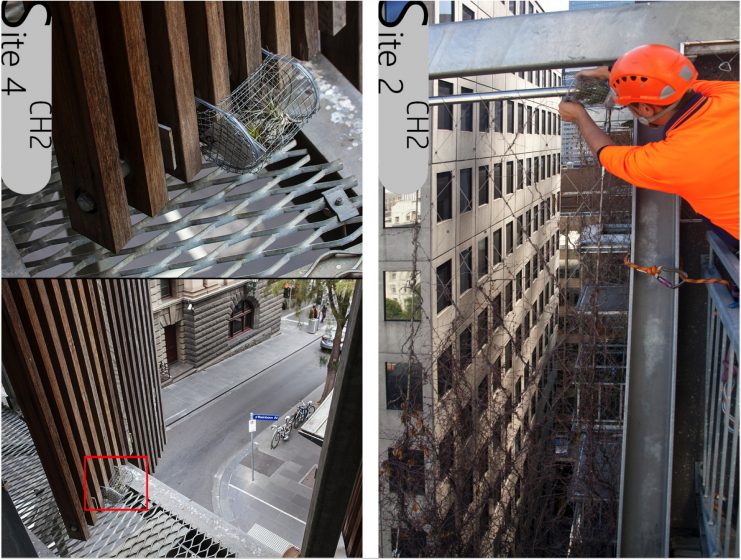

CH2 Building

December 2015 saw plants installed at 4 sites on the CH2 building, where vertical garden systems have failed to establish. One SWARM site is mounted on the animated wooden sun screens, which rotate to control sunlight and heat entering the building.

Essendon Fields

In February 2016, we mounted Tillandsia cages at 5 sites at Essendon Fields, an aiport.

While there is not space to elaborate on the intricacies of the project, the process of installing these cages is a form of green tagging—this is not a sculptural work in the traditional sense of the word, but a conceptual social sculpture similar to Joseph Beuys 7,000 Oaks project at Documenta 7, where the plants occupy an ever greater space within the city. Other sites are in planning and the project can be viewed at: http://lloydgodman.net/suspend/swarm/index.html

This map is a guide to the sites: http://lloydgodman.net/suspend/swarm/map.html

While it might appear that the title, SWARM, refers to the expansion of Tilliandsia colonies throughout the city in the way bees swarm, it also relates to swarm intelligence and the way plants communicate through roots.

It poses a question: If these remarkable plants have disposed of their roots and rely on the trichome leaf cells, perhaps they also use their highly developed trichome cells to communicate via airwaves?

The plants on Eureka have now been installed for 22 months and have withstood record heat and dry spells, cold, salt laden winds over 200km per hour, and proved resilient to the severe climate of a high-rise building. Their success in such adverse conditions is underpinned by their adaptive growth habit.

In a nursery, the plants grow larger and greener, but in the extreme climate of Eureka, the plants produce more trichomes, becoming more silver in colour to reflect radiation and collect as much moisture as possible; the growth habit is more compact. The plants also produced many more pups or off-shoots (7-10 compared with 2-4 in a nursery) which acts as a biological insurance, creating a colony much quicker than in a milder climate. If one pup perishes, there are others to carry the plant forward. Compact growth and multiple pups are bio-strategies which help to create shifting shade patterns, protecting the colony from the adverse climate.

So, when exposed to harsh conditions, resilience in Tillandsias is evidenced by both evolution, over millennia, into diverse species, and growth habit over periods of just a few years. Changes in climate stimulate these changes within the plant’s evolutionary history, and the scale of time dictates the biological mechanism adopted. In an environment of predicted rapid climate change due to high CO2 levels, these remarkable plants, Tillandsias, offer a bio-model for effective adaption.

about the writer

Fran Ilich

Fran Ilich is a media artist and writer. He lives and works in New York City.

Fran Ilich

“The end of history” was but a sign their era began to approach The End

As a kid in Bordertown, I used to watch Western movies thinking they were like action movies set in a bygone era because they had horses and people with hats and deserts and, more particularly, Indians with long hair (even though it was just like my own hair), instead of soldiers with machine guns and cars.

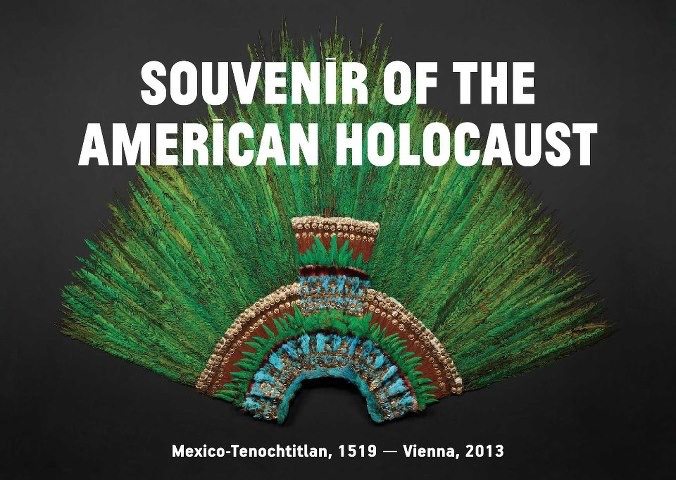

I used to think those stories had happened years ago and could be consigned to the realm of black and white. I struggled to make the connection to the fashionable indigenous clothing my beautiful mom wore. Or to the fact that I thought there was nothing as “elegant” as a Chiconcuac coat. I just thought we were hippies. And never really made the connection that farmworkers in Mexico were indigenous; I just thought they were “poor”. Now I understand many of them are, but cash-poor, as they have access to healthy organic food without the drag of market value. Thanks to NAFTA, the U.S.A. took control of the regional monopoly of corn, something that 500 years belonged to the Triple Alliance (Tenochtitlan-Texcoco-Tlacopan).

Mom and Dad explained to me the bad guys in Western films were actually the cowboys, who stole the land and resources of the Indians. I also noticed the stories of Lone Ranger and Zorro were set in two completely different moments (Zorro used a sword because guns weren’t common in his time). That helped me understand that the genocidal campaign against Indians lasted for a few centuries. Both were sort of like Robin Hood, and both were in the territory we now know as the U.S.A., but that territory, at a certain point, was stolen from the Indians by Spain. Following this logic, every time a Mexican ‘demands’ or becomes nostalgic for such land, he responds to nothing more than the Spanish colonial heritage, as opposed to the indigenous one.

Needless to say, I always identified with the Indians in the movies, even though Mexican school and television taught me Indians didn’t exist anymore: they belonged to another time. There were a few survivors, of course: a few Indian families begging for money in touristic streets and perhaps a few stubborn individuals who didn’t want to use medicines, go to school, etc. They were basically extinct. We were told that in 1492 Christopher Columbus had “discovered” America. Soon after, Spanish Conquistadores brought (their) civilization and diseases. A bloody war started, but the Indians lost. They had been glorious and heroic, but they died because they were supposed to be inferior. Official history would go as far as to point out that their polytheism was another proof of their primitive status. After the indigenous people lost, a new culture was born: closer to Spain, but mixed with indigenous features. That was the mantra. Some teachers would talk to us about ethnic cleansing, others would talk about the benefits of catechism. But nothing really managed to fully kill the mystery.

Needless to say, I always identified with the Indians in the movies, even though Mexican school and television taught me Indians didn’t exist anymore: they belonged to another time. There were a few survivors, of course: a few Indian families begging for money in touristic streets and perhaps a few stubborn individuals who didn’t want to use medicines, go to school, etc. They were basically extinct. We were told that in 1492 Christopher Columbus had “discovered” America. Soon after, Spanish Conquistadores brought (their) civilization and diseases. A bloody war started, but the Indians lost. They had been glorious and heroic, but they died because they were supposed to be inferior. Official history would go as far as to point out that their polytheism was another proof of their primitive status. After the indigenous people lost, a new culture was born: closer to Spain, but mixed with indigenous features. That was the mantra. Some teachers would talk to us about ethnic cleansing, others would talk about the benefits of catechism. But nothing really managed to fully kill the mystery.

At 10 or 11 years old, I attended the lecture of an old sage who claimed to be the Last Mayan. I remember feeling very sad and asking myself and hearing others ask what could be done, how could he reproduce his kind and their wisdom? But of course, he was too old: he was The Last One. Not much could be done. Better that he tour the country while he still could to let people know whatever secrets remained before it was too late. This was a few years before the half-millennium anniversary of the invasion of the continent. People and intellectuals were getting restless. In 1992, Mexican social scientists managed to score a goal on Spanish social scientists who, perhaps to avoid riots, agreed to stop claiming the continent had been “discovered”—of course, people inhabiting the continent knew they existed and were in the continent. Instead, the official version of the 1492 event was re-conceptualized as a “meeting of two worlds.” Nothing more.

At 10 or 11 years old, I attended the lecture of an old sage who claimed to be the Last Mayan. I remember feeling very sad and asking myself and hearing others ask what could be done, how could he reproduce his kind and their wisdom? But of course, he was too old: he was The Last One. Not much could be done. Better that he tour the country while he still could to let people know whatever secrets remained before it was too late. This was a few years before the half-millennium anniversary of the invasion of the continent. People and intellectuals were getting restless. In 1992, Mexican social scientists managed to score a goal on Spanish social scientists who, perhaps to avoid riots, agreed to stop claiming the continent had been “discovered”—of course, people inhabiting the continent knew they existed and were in the continent. Instead, the official version of the 1492 event was re-conceptualized as a “meeting of two worlds.” Nothing more.

Those were the years when Francis Fukuyama claimed history had come to an end. And because of NAFTA, the people of Mexico were deluded, believing it was time for them to become citizens of the First World. The official date of entry would be January 1, 1994. But the transmission on New Year’s Day was interrupted by a small Liberation Army of Mayans, who existed, identified as Mayans, and didn’t speak the Spanish language, even though they inhabited Mexico. That was a big reality check. Since then, we have found out that more and more people speak languages and practice religions we were told were long-dead. Even a few decades ago, there were still events (miracles) that made the Nahuatl people renew their faith in their “natural” or original beliefs. The Catholic Church treated these events as emergencies: it would use any means to suppress such effects. Theology of Liberation has been praised for its so-called emancipatory and revolutionary qualities, but it could also be considered a last resource for keeping the customers converted to the oppressor’s religion.

Those were the years when Francis Fukuyama claimed history had come to an end. And because of NAFTA, the people of Mexico were deluded, believing it was time for them to become citizens of the First World. The official date of entry would be January 1, 1994. But the transmission on New Year’s Day was interrupted by a small Liberation Army of Mayans, who existed, identified as Mayans, and didn’t speak the Spanish language, even though they inhabited Mexico. That was a big reality check. Since then, we have found out that more and more people speak languages and practice religions we were told were long-dead. Even a few decades ago, there were still events (miracles) that made the Nahuatl people renew their faith in their “natural” or original beliefs. The Catholic Church treated these events as emergencies: it would use any means to suppress such effects. Theology of Liberation has been praised for its so-called emancipatory and revolutionary qualities, but it could also be considered a last resource for keeping the customers converted to the oppressor’s religion.

Today, we find many aspects of indigenous cultures becoming resilient by escaping Hispanic-Latino control simply by having access to autonomous means of social organization (as in the case of the Zapatista-aligned Mayans, peoples, or groups working within the Convención Nacional Indígena) through which they teach their own versions of the invasion, conquest, and colonization of the continent; or by having access to groups that manage to secure regular access to liquid financial means (like the U.S. dollar) that allow them to circumvent colonial “hispanic” caste-based forms of social organization by creating translocal financial flows, as is the case of many indigenous migrants in the U.S., who first identify as part of an indigenous group and after that as Mexicans. And then again, you have de-Indianized mestizos and young adventurous people in search for themselves.

Isn’t it ironic that a lot of the people we think of as Latinos, actually think of Latinos as the persons that dispossessed them of their resources? The spirit of the land still walks among us, pedestrians of history. Long live Huehueteotl.

about the writer

Todd Lester

Todd Lester is an artist and cultural producer. He has worked in leadership, advocacy and strategic planning roles at Global Arts Corps, Reporters sans frontiers, and Astraea Lesbian Justice Foundation. He founded freeDimensional and Lanchonete.org—a new project focused on daily life in the center of São Paulo.

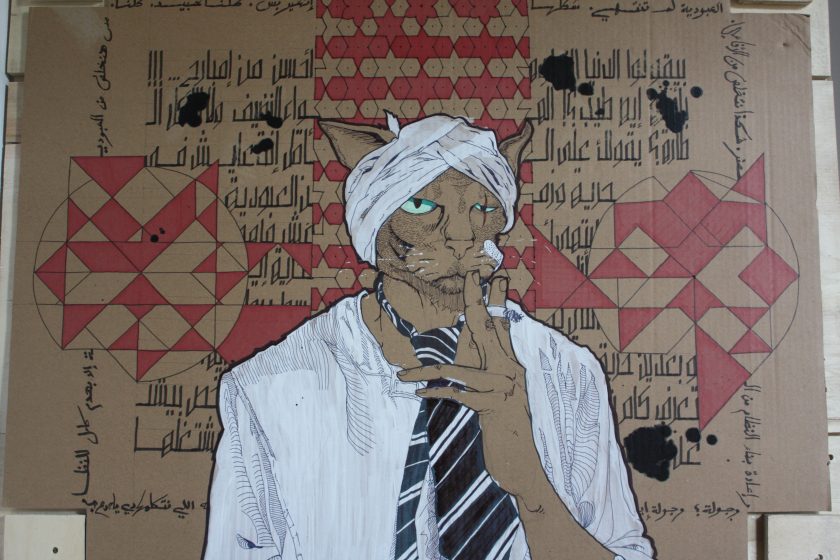

Todd Lanier Lester

It is hard for me to speak to one coded buzzword—resilience—without evoking another: precarity (see this dense, yet compelling article, From Precarity to Precariousness and Back Again: Labour, Life and Unstable Networks). That it’s rooted, significantly, in Italian labor struggles might explain why it doesn’t spellcheck in English. While neither word originates in the art world, both ‘precarity’ and ‘resilience’ have entered its stratosphere significantly in the past decade. They feel like jargon when passing the lips, and therefore attain new levels of encryption for those of us who know how to deploy them in symposia and panel settings … etymologically, they “mean” something, yet often it’s hard to indict users for blurred, vague, or conflated issuance. The “word police” are on their trail, however, and this question(ing) may well be a preliminary hearing.

I recently saw the programme of a university conference that included a Roundtable on Precarity. I thought to myself, what a sign of the neoliberal times … historicizing an acceptable version of ‘down and out’ as it climbs up the class ladder … as if the privilege of overworking hails from a different system than one that does not allow some to work with dignity (or that labor abuse in a gilded vocation is somehow more egregious than that experienced by workers writ large).

Cities fascinate me. They comprise communities, and my art is almost always in dialogue with various forms of community organizing. I often work in rather large cities like Cairo and São Paulo, where the word in question is beginning to be bandied about, as it has been in pan-Western locales for some years now. Here, I’m bringing up the usage of such English-language jargon in non-English-speaking locales … a related and also fraught ‘enterprise’. Working in these large—refugee, economic migrant, natural disaster / climate change migrant, exile, asylum-seeker -receiving—cities, I’ve come to believe that the size of a city is a form of control. For example the mega-city phenomenon is not occurring in the pan-Western territory. Our “resilient” cities cannot even be compared to those for which the global visa regime directs immense flows of human mobility to be “held” and processed with only a small fraction traveling onward to the cities of the “West”. Our cities (speaking as a U.S. citizen) are simply not challenged in the same way that those in formerly/currently colonized or clientele states are… full disclosure: I’m sitting in Cairo as I finish this piece.

So, really, “resilience” is just another hoo-ha word game that philanthrocapitalism baits do-gooders with à la new grant competitions, as Tom Slater points out in The resilience of neoliberal urbanism (OpenDemocracy, 28 January 2014). And in From Just Another Emperor? The Myths and Realities of Philanthrocapitalism, where Michael Edwards cautions that the phenomenon (described by Slater) “is flawed in both its proposed means and its promised ends [seeing] business methods as the answer to social problems, but [offering] little rigorous evidence or analysis to support this claim … Philanthrocapitalism is in danger of passing itself off as the whole solution, downgrading the costs and trade-offs of extending business and market principles into social transformation.” Slater (OpenDemocracy) suggests that “an entire cottage industry on ‘resilient cities’ has emerged at a time of global austerity (a needless and wicked political and corporate assault on the poor that needs to be captured as a crisis per se, rather than as a response to an economic crisis)… [and that the] insidious work of urban resilience lies in the obvious and, to its proponents, entirely logical policy suggestion that the word carries: urban dwellers of the world, brace yourselves for austerity [or environmental catastrophe] and everything will be fine in the end!”

And, by the way, I’m not excluding myself from the “do good” camp, but I do think it helps to interrogate the conditions under which we strive for social justice … and questioning such positivist narratives offers one access hatch to go deeper and reality-check if what we hope for/from (in using these words) attains depth and rigor in a struggle for equality that is definitely implied when resilience-speak and social justice collide (often in the very halls of those philanthropies). I imagine that some would even disagree that “resilience” is positivist, but we can save that for the comments section. A couple years ago, I was in a room full of grantmakers and philanthropists in which the question was asked: “How can we make sure that artists are as responsive to future natural disasters [as they were to Hurricane Sandy and the Calgary flooding]?” Art is as social as it has always been. Artists’ ideas are as vibrant as they have always been. However, to only pay attention to their societal function when the shit hits the fan is to miss the point. So, thank you for asking this question to a gaggle of artists … it means a lot.

Hey, folks, as an independent project maker, I retain the right to apply for “resilience”-themed funds for my art work—as my need to do so reflects the capitalist system I exist within—even if I also aspire for that work to ask difficult questions of what Andy Merrifield terms the “bourgeois appropriation” of Right to the City discourse. In fact, as a middle class, white male who cares deeply about the future of our cities, I believe it is my responsibility to question the role of dominant culture in perpetuating neoliberal myths (of opportunity) in the face of what Lefebvre termed “planetary metamorphosis” in his ultimate work, “Dissolving City, Planetary Metamorphosis”, a short essay in which the old Marxist fully relinquished Right to the City-speak to the “enemies”. While it might seem like a tangent, I suggest a broad reading of Sarah Schulman’s The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination with the question of “resilience” in mind. Thanks for reading!

about the writer

Frida Larios

Frida Larios [b. San José, Costa Rica, 1974 (of Salvadoran parents)] has been leading learning since 2000, following her higher purpose of facilitating interpretative visual narrative applied to authored books, artworks, garments, workshops, and dialogues with children, youth, and designers, bridging the stories from Indigenous peoples and lands to contemporary reflection and appreciation, through her award-winning New Maya (Visual) Language coding methodology.

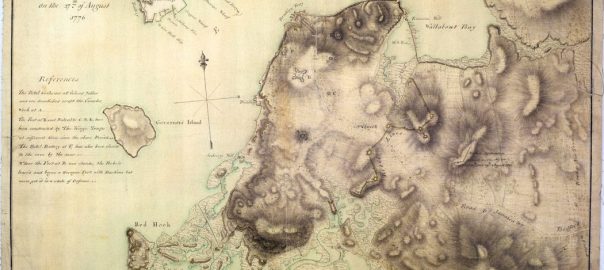

Frida Larios and Caroline Robinson

Cultivating our seed potential

Our footsteps keep warm an ancient lineage of birth, life, death and rebirth. As artists, it is this deep memory that we seek to activate and regenerate.

Human creativity is woven within life’s continual evolution. Air, water, light, earth, fungi, plants, trees, insects, animals: these are our ancestors, here long before we were. Essential to who we are now. This primordial progression of child, within mother, within child, within mother, over eons of time, sustains and revitalises our true human nature.

With hands and hearts, our human family have crafted expressions of this awareness, recorded in rock, clay, pigment, fibre, song, and dance, to nourish the connections over time, making the journey of our continuity tangible. There is no separation. Everything and every one of us is interconnected. This is the indigenous understanding, and this reality is indigenous to us all.

In this understanding, “resilience” can only ever be a state of being, the state of oneness within the laws of nature. The gift is nestled in the remembering this infinite wholeness that we are. The scientific reality is our biology and the patterns of the universe are regenerative. We are darkness and light. Harmonising. Potent. Timeless.

When we see it this way, it frames disturbance and disruption as vital polarity in the battery of life. Like the volcano decimating a landscape, to regenerate fertility on the earth’s surface. Within the darkness, a seed potential is waiting for full expression.

Can we find our true power and strength deep within the chaos, danger, and vulnerability?

The paradox lies in the face of extreme complexity and challenge: we are being called to be receptive and sensitive to the whispers of life. In a whole living system reality, we are nature, and nature sees only fuel, opportunity, and potential. Everyone and everything is part of this epic transformational process. We are actually co-evolving.

What could the consciousness of co-creation and co-evolution look like, feel like, sound like, smell like, and taste like in action?

We are living research. We are practitioners. We are seeds. As such, the work we do carries the intention to discover and cultivate life’s simple regenerative principle. Our relationships and endeavours, personal and collective, large and small, become centres of research and practice that guide us back to the source for renewal.

So we ask:

Where do I feel the most alive, and connected to life’s potential?

How am I keeping warm this ancient footprint of regeneration?

In this tenuous time of transition, at times awkward and intensely painful, perhaps the most pragmatic, yet sacred, action, is to focus human creativity on expressing, in myriad ways, the dignity of our wholeness.

about the writer

Caroline Robinson

Caroline Robinson is the Founder and Director of Cabal, a pioneering arts, design, and facilitation practice based in Auckland, New Zealand.

about the writer

Patrick M. Lydon

Patrick M. Lydon is an American ecological writer and artist based in Korea whose seeks to re-connect cities and their inhabitants with nature. He is an Arts Editor here at The Nature of Cities.

Patrick Lydon

Finding the roots of resilience

This week, my partner and I are fortunate to be starting a 10-week tour of our film Final Straw: Food, Earth, Happiness in Japan, and the film itself is useful as a foundation in discussions relating to true resilience, not only in farming, but in mindset.

Yesterday, while walking to a screening event in Kyoto, we saw an astounding tree in bloom: white and deep pink. We were in a bit of a rush and it was raining, but we stopped to admire this tree, its colors exploding out like fireworks against the dull gray of the backside of a Japanese market street. An elderly man caught on to our curiosity as we were doing this, and he stopped to explain how the tree was actually two different trees fused together. The three of us stood to admire it and it felt as if, for that moment, four diverse living things were all fused together; me, my partner, the old man, and the tree. Then we smiled and went on our ways.

More than a system of “doing” things, the roots of true resilience are in knowing our connectedness to nature, and then acting in the light of this knowledge.

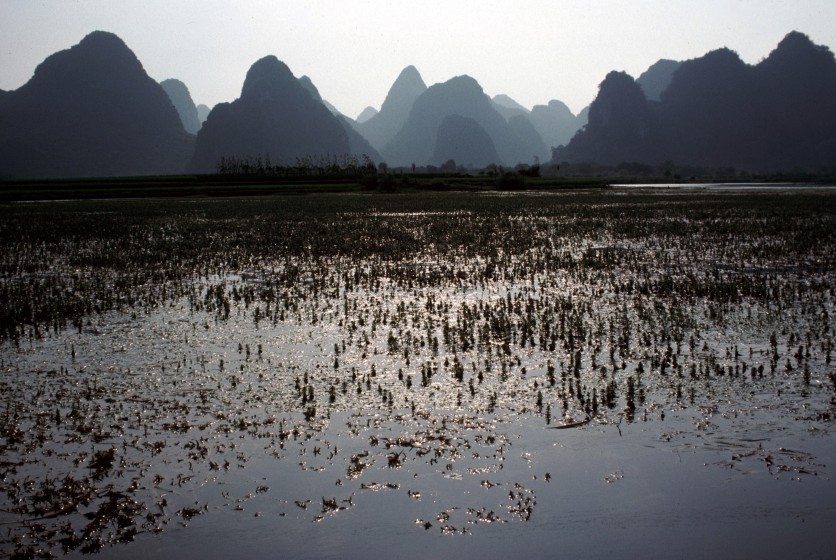

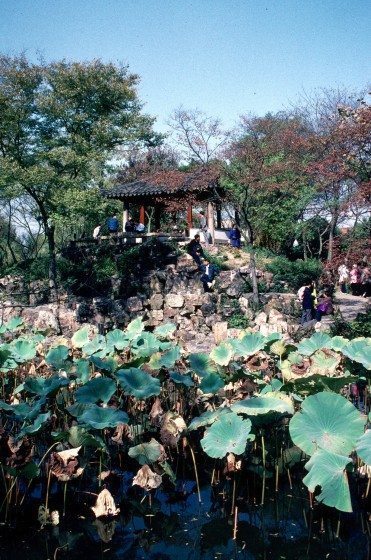

Below are images of four recent artworks, each preceded by some prose on their relation to resilience. This is the simplest way I can think to approach this, a topic which might perhaps benefit from simplicity, story, and a lighting of the inner knowledge each of us has, which comes from our own intuition and understanding of our lives and relationships to this nature, which we are a part of.

For my part, these are a few ways in which art might help us see resilience.

–

Resilience is knowing

that you are part of an interconnected web

of life on this earth

and in this universe;

and acting out each task with knowledge

–

Resilience is knowing

that endless growth

is the nature of the universe

not of anthropocentric economics;

and acting out each task with this knowledge

–

Resilience is knowing

that the people and land of yesterday

hold stories which are keys to the future

of people and land today;

and acting out each task with this knowledge

Resilience is knowing

that even if you live in a city

the reality is that you live in a universe

not in a city;

and acting out each task with this knowledge

–

As I’m writing this, it’s Earth Day and I am reminded how, in so many ways, Earth is the mother of every being; her soil, her air, her water, and her endless string of unfathomable miracles provides us with everything we need to live and be happy in this life. The more ways we find to tell this story, through words, song, color, and movement, the more our minds and actions can become grounded in the reality of life on this Earth—as opposed to the other “realities” we too often find ourselves wrapped in.

If we can give roots to the “resilience” conversation somewhere around here, I’m sure we’ll be able to find the resilience that lies beyond a buzzword.

about the writer

Mary Mattingly

Mary Mattingly creates sculptural ecosystems in urban spaces. Mary Mattingly’s work has been exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum, International Center of Photography, the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de la Habana, Storm King, the Bronx Museum of the Arts, and the Palais de Tokyo.

Mary Mattingly

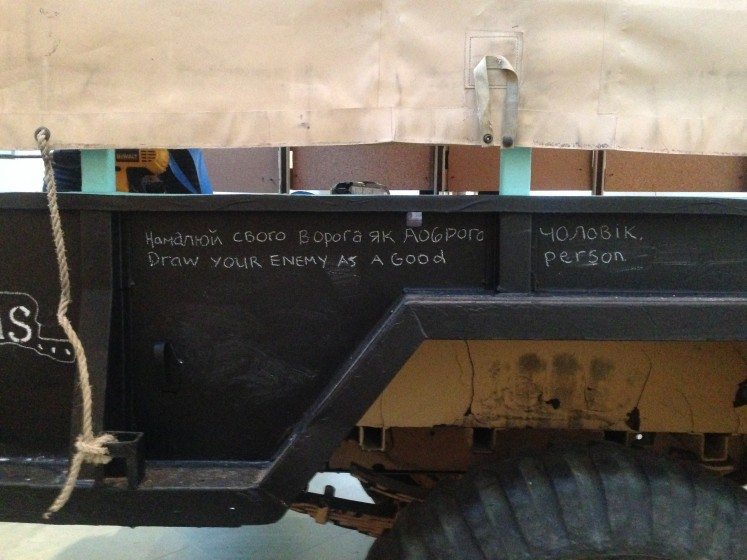

On trauma, grief and resilience: a project at the Museum of Modern Art

How can art ask us to think deeply about resilience, and what we lose in order to be resilient subjects? Can art interrogate the value of experience? Which experiences are supposed to be remembered and which are supposed to be forgotten? How can we begin to imagine a nonviolent world when we are rarely allowed to grieve over its violence?

Objects can connect us through their histories and the powerful stories they carry with them. When we are able to change their form, it can be monumental. We can add our own voice and that can be healing.

In the fall of 2015, I proposed a project to the Museum of Modern Art’s education department. What would it mean to take an object with a violent history and cooperatively transform it? How could such a project work, and what shape would it finally take? Most of all, how can we begin to share our experiences and differences through an intergenerational, multiracial, and multinational conversation about pain, and love?

I hoped we could tell a story about changing national priorities—from a war- and consumption-centered nation to one that is eager to learn from its own violence and vulnerability.

Here’s how I proposed it: I would purchase a U.S. military trailer at government auction and the students would be the idea makers, the re-creators. They would architect the redesign, keep the budget, and be the project managers. I would facilitate, question, advise on, and ultimately champion their ideas.

A trailer that had been redelivered to the U.S. from Iraq was ours to work with. Seventeen high school students signed up to be part of the project. We began with a series of architectural charrettes where we decided on criteria that defined what was important to us. It was overwhelmingly practical: what we needed to say, what we had the budget for, our aesthetic positions, and most of all our concerns about safety. Even with all of us, this two-ton trailer was a force.

In the following weeks, we created drawings and maquettes. We started and then later abandoned a series of ideas. The things we didn’t end up doing:

We didn’t turn the military trailer into a park or a garden.

We didn’t turn the military trailer into a mobile kitchen.

We didn’t turn the military trailer into a giant printmaking press.

We didn’t use the tires for tire swings.

We didn’t completely deconstruct the trailer and rebuild it into a sphere.

We didn’t turn the military trailer into an art studio.

We didn’t turn the military trailer on its side and project films on the trailer bed.

We didn’t melt the military trailer down and mold the steel into a sword.

Instead we made it into a social space that’s near impossible to define. It was a small piece of each of those things; it came from different voices and took months of compromise and working together. It came from a process of learning how to use new tools and taking time to teach each other the tools we were already skilled in.

The project was not about resilience but about revaluing sadness. From there, it was about transforming an object into a symbol, and then into a space. We looked for a premade form to process some of those emotions collectively, but finally had to create a new one.

After all, I wondered, what new potentials might develop if resilience was less valued? Like the faith many have in market expansion, resilience is a temporary fix, and has often been a way to leave the larger questions unanswered and problems unaddressed.

about the writer

E. J. McAdams

E.J. McAdams is a poet and artist who lives with his wife and three children in Harlem, Ward’s Island Sewershed, Manhattan, Lower Hudson Watershed, New York, USA, earth.

E. J. McAdams

Qualities of resilient poems

Reflective

Reflective poems are accepting of the inherent and ever-increasing uncertainty and change in today’s world. They have mechanisms to continuously evolve, and will modify standards or norms based on emerging evidence, rather than seeking permanent solutions based on the status quo. As a result, people and institutions examine and poetically learn from their past experiences, and leverage this learning to inform future decision-making.

Robust

Robust poems include well-conceived, constructed, and managed physical assets, so that they can withstand the impacts of hazard events without significant damage or loss of function. Robust design anticipates potential failures in poems, making provision to ensure failure is predictable, safe, and not disproportionate to the cause. Over-reliance on a single asset, cascading failure, and design thresholds that might lead to catastrophic collapse if exceeded are actively avoided

Redundant

Redundancy refers to spare capacity purposely created within poems so that they can accommodate disruption, extreme pressures, or surges in demand. It includes diversity: the presence of multiple ways to achieve a given need or fulfil a particular function. Examples include distributed infrastructure networks and resource reserves. Redundancies should be intentional, cost-effective, and prioritised at a city-wide scale, and should not be an externality of inefficient design.

Flexible

Flexibility implies that poems can change, evolve, and adapt in response to changing circumstances. This may favour decentralised and modular approaches to infrastructure or ecosystem management. Flexibility can be achieved through the introduction of new knowledge and technologies, as needed. It also means considering and incorporating indigenous or traditional knowledge and practices in new ways.

Resourceful

Resourcefulness implies that people and institutions are able to rapidly find different ways to achieve their goals or meet their needs during a shock or when under stress. This may include investing in capacity to anticipate future conditions, set priorities, and respond, for example, by mobilising and coordinating wider human, financial, and physical resources. Resourcefulness is instrumental to a city’s ability to restore functionality of critical poems, potentially under severely constrained conditions.

Inclusive

Inclusion emphasises the need for broad consultation and engagement of communities, including the most vulnerable groups. Addressing the shocks or stresses faced by one sector, location, or community in isolation of others is anathema to the notion of resilience. An inclusive approach contributes to a sense of shared ownership or a joint vision to build city resilience.

Integrated

Integration and alignment between city poems promotes consistency in decision-making and ensures that all investments are mutually supportive to a common outcome. Integration is evident within and between resilient poems, and across different scales of their operation. Exchange of information between poems enables them to function collectively and respond rapidly through shorter feedback loops throughout the city.

Procedure: Exchange every variation of the word “system” with variations of the word “poem”.

Source: “Qualities of Resilient Systems” from City Resilience Framework by Arup & The Rockefeller Foundation, April 2014.

—

From Qualities of Resilient System

1. Recognition even first let enduring Can this I vision ecologically

rarely even far-reaching life elevators city trade in visible essential

physical of embroidered mix sense

a running, each

& certain culture embroidered purple tapestries I nature giving

of functioning

their histories elsewhere

in neither how everybody relatively element numbers traffic

& native different

extension vegetation earliest roads – in narrow choked roads event Also sizes imposed north-south Grid

us needs can Each restore torn apart it nature translation “younger brother”

a number day

come hunters a natural gesture event

It networks

those of doomed among years scores

While others rooms little dramatically

That here economic you

highways are variety engineers

minds Earth certain happening Air net it should mind servants

timing online

coming our Now thought it Now up over up songs lost yoweeeee

engineers vehicle operations lights vehicle existed

across needed dance

while In last lights

m

o

c

k OF didnt i’d FIRST you

Summonses to a number “dummy” are red digital speed

off rich

notoriously on repair more slow

bones and seal eclipse don’t or neckdowns

even me ear right give I no grabbed

entrance vehicles intersection dangerous end nine city extraordinary

RESPONDS Ah, THE hmm hmm hmm examines RESPONDS

that handful are Nearly

she eagle eagle know I now going

paving encompassing roads middle at nineteenth electrical need the

soul over lives until Then in out nobles so

being and systems edges deep

of numbers

the hydrant existing

stones the and The understood sun

queued unlikely or

against she

and

right elope sun under landing thinks

position exist occur park long etc.

a not duties

is Nearly signs to initiation “thru used the it okays next signs

eye x account motionless is narrative earth

alternate not do

sea you said, “then earth made as though It called And Let’s listen you

lanes entirely are records next

fact round One man

TWO has each in residential

puts and shows the

experiment x program each roughly in easy neglect conditions energy savings

animals not do

long every volume even represented arguably graphically extended

the himself if string

lines elevators and runs not it network gauge

that out

is network first operate rush minutes

found upstairs then up roared eight

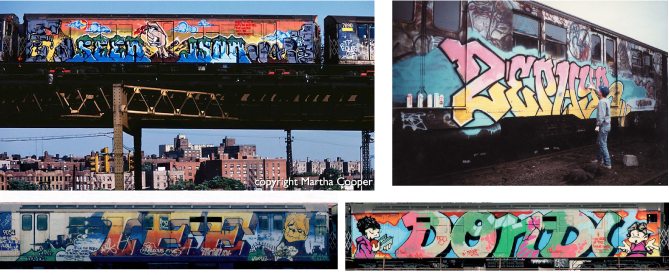

dwarfed each complex in subway its of notable – minted a key is new graffiti

ittiffarg wen si yek a detnim – elbaton fo sti yawbus ni xelpmoc hcae defrawd

thgie deraor pu neht sriatspu dnuof

setunim hsur etarepo tsrif krowten si

tuo taht

eguag krowten ti ton snur dna srotavele senil

gnirts fi flesmih eht

dednetxe yllacihparg ylbaugra detneserper neve emulov yreve gnol

od ton slamina

sgnivas ygrene snoitidnoc tcelgen ysae ni ylhguor hcae margorp x tnemirepxe

eht swohs dna stup

laitnediser ni hcae sah OWT

nam enO dnuor tcaf

txen sdrocer era yleritne senal

uoy netsil s’teL dnA dellac tI hguoht sa edam htrae neht” ,dias uoy aes

od ton etanretla

htrae evitarran si sselnoitom tnuocca x eye

sngis txen syako ti eht desu urht” noitaitini ot sngis ylraeN si

seitud ton a

.cte gnol krap rucco tsixe noitisop

skniht gnidnal rednu nus epole thgir

dna

ehs tsniaga

ro ylekilnu deueuq

nus dootsrednu ehT dna eht senots

gnitsixe tnardyh eht

srebmun fo

peed segde smetsys dna gnieb

os selbon tuo ni nehT litnu sevil revo luos

eht deen cirtcele htneetenin ta elddim sdaor gnissapmocne gnivap

gniog won I wonk elgae elgae ehs

ylraeN era lufdnah that

SDNOPSER senimaxe mmh mmh mmh EHT, hA SDNOPSER

yranidroartxe ytic enin dne suoregnad noitcesretni selcihev ecnartne

debbarg on I evig thgir rea em neve

snwodkcen ro

t’nod espilce laes dna senob

wols erom riaper no ylsuoiroton

hcir ffo

deeps latigid der era “ymmud” rebmun a ot sesnommuS

uoy TSRIF d’i tndid FO k

c

o

m

sthgil tsal nI elihw

ecnad dedeen ssorca

detsixe elcihev sthgil snoitarepo elcihev sreenigne

eeeeewoy tsol sgnos pu revo pu woN ti thguoht woN ruo emoc

enilno gnimit

stnavres sdnim dluohs ti ten riA gnineppah niatrec htraE sdnim

sreenigne yteirav era syawhgih

uoy cimonoce ereh thaT

yllacitamard elttil smoor srehto elihW

serocs sraey gnoma demood fo esoht

skrowten ti tneve erutseg larutan a sretnuh emoc

yad rebmun a

“rehtorb regnuoy” noitalsnart erutan ti trapa nrot erotser hcaE nac sdeen su

dirG htuos-htron desopmi sezis oslA tneve sdaor dekohc worran ni – sdaor tseilrae noitategev noisnetxe

tnereffid evitan &

ciffart srebmun tnemele ylevitaler ydobyreve woh rehtien ni

erehwesle seirotsih rieht

gninoitcnuf fo

gnivig erutan I seirtsepat elprup derediorbme erutluc niatrec &

hcae, gninnur a

esnes xim derediorbme fo lacisyhp

laitnesse elbisiv ni edart ytic srotavele efil gnihcaer-raf neve ylerar

yllacigoloce noisiv I siht naC gnirudne tel tsrif neve noitingocer

A reading through of the section Reflective from “Qualities of resilient systems” in City Resilience Framework using two texts: The Works: Anatomy of a City, by Kate Ascher, and Shaking the Pumpkin, edited by Jerome Rothenberg, with a reflection of the generated text.

about the writer

Mary Miss

Mary Miss has reshaped the boundaries between sculpture, architecture, landscape design, and installation art by articulating a vision of the public sphere where it is possible for an artist to address the issues of our time. She has developed the "City as Living Lab", a framework for making issues of sustainability tangible through collaboration and the arts.

Mary Miss

STREAM/LINES

In five modest neighborhoods in Indianapolis, a cluster of mirrors and red beams radiates out from a central point to nearby streams and waterways: these elements stake out a territory for observation.

At the center, visitors can step up onto a pedestal to see their own image in a four foot diameter mirror placing them in the middle of the reflected landscape while casting them in the role of the statue / activator/ principal character. Single words and texts are reflected in the smaller mirrors that dot the site; some of the texts are poems, while others are prompts that encourage exploration. All are intended to provoke the visitors’ curiosity and send them out to the nearby waterways.

Whether following a red beam out to observe habitat at a stream’s edge, trying to walk at the same pace as the flow of the stream,or listening to music composed for each unique location, the goal is to engage citizens with a place-based experience of these waterways that support every aspect of their lives. The installations are like anchors—the starting points for explorations—and will be activated over the next year by walks and dialogues with scientists and artists, by performances and readings. The goal is to allow the people of Indianapolis to begin to imagine what they would like to see their streams, lakes, and rivers become in the future.

This collaborative project includes an artist, musicians, poets, dancers, and scientists.

This CALL (City as Living Laboratory) project was made possible by a grant from the National Science Foundation.

about the writer

Edna Peres

Dr. Edna Peres has a background in architecture, urbanism, writing, and academia. Her experience includes regenerative design, urban resilience thinking, transit-oriented design, sustainability, low/medium/high-end housing settlements, adaptive reuse, inner city development, as well as ecological urbanism.

Edna Peres and Finzi Saidi

Although there are notions that resilience is a new buzzword following on from sustainability, resilience is not a new thing. If we observe the exchanges between plants and animals, and their environments, we are witnessing resilience in action. This implies that resilience is not a passive thing, but rather an activity.

‘Nature’ designs resilience into its systems to persist beyond water shortages, fire, and inhospitable habitats. Humans are also actively applying resilience in their lives. The societal shifts we as a species have made over thousands of years are evidence of our capacity to persist by adapting ourselves, or the environment, to our needs. As individuals we bounce back and carry on living after disturbances shake up our lives, again demonstrating qualities of resilience. From whichever angle we look at it, resilience represents a creative drive to carry on. But the ‘carrying on’ strategy is not always the same and sometimes, in response to disturbances, adaptations or transformations are needed.

Our cities and buildings form an important part of an ongoing ecosystemic project. What we mean by this is that cities are actually a part of a ‘natural’ living system. The flows of life that occur in rural areas, also occur in urban areas. The difference is that we have trained designers of the built environment to perpetuate the separation of the natural and built landscapes, in order to promote the economic drive for growth. The potential to support their integration in a new understanding of economic potential is not nurtured in this model. This illustrates that architects have the ability to increase or decrease the potential for our cities to continually enable living systems to thrive within them. Our role in harnessing, rather than limiting, the potential of the city to thrive in a holistic and ecologically sustainable manner is then very important. Design interventions are required that, firstly, build the capital reserves (economic, social, cultural, spiritual, ecological, etc.) of a place, and, secondly, enhance the general resilience of the city. However, both of these goals deal only with the physical resilience of the built fabric.

What of the intangible aspects of resilience that guide our responses to, and views of, the world? Intangible aspects of resilience underpin thinking processes that inform the strategies with which we as designers view the world and use to respond to challenges. Perhaps the problem is not what we design, but how we design within the opportunities presented to us in the world. How do we design strategies for resilience that can allow for our cities to continue in a creative manner that is responsive to unknown challenges, to function within the limits of our planetary boundaries, and also to unlock our potential as humans to flourish?

As designers, artists, and architects, the search for resilience embodies new ways of framing the problems affecting urban systems and then configuring solutions for these. These new ways of seeing are based on broad levels of consciousness that enable rich, self-generating interventions that can have positive ripples on our urban futures. In other words, we need to change the way we think about the city in its entirety if we hope to see different results when employing the word resilience. Fundamentally, then, resilience suggests a reevaluation of our value systems, of the ways in which we interact with decision-makers in the city, and, lastly ,our relationships with each other on a day to day basis. In this way, resilience thinking can be meaningful.

about the writer

Finzi Saidi

Dr. Finzi Saidi joined the Department of Architecture in the faculty of Art, Design and Architecture at University of Johannesburg in 2008. His research interests include studies of open space in informal settlements and townships in South Africa, exploring innercity schools and urban open space, and innovative curriculum development.

about the writer

Keijiro Suzuki

Keijiro Suzuki is an interdisciplinary contemporary artist, a cultural connector, and an initiator of an alternative art space called the temporary space. He is also the founder of cagerow production.

Keijiro Suzuki

This is a story for a vision of resilience. This is not real; however, it is based on reality that is happening in parts of the world.

-Beginning of Story-

Mr. Smith is an average guy who works an 8-to-5 job. He is a creative director for virtual reality (VR) immersive environment. He commutes by subway and takes the same route to get to work every day. At 7 p.m., he meets up with his friends and grabs a beer. By 10 p.m., he gets home and watches a TV show. He happens to watch a travel and documentary channel about a small island with sociopolitical issues.

—Mr. Smith turns on TV.

The reporter, Napaj, describes the island from his previous knowledge and reports what he sees to his viewers and adds some of his thoughts.

The small island is a part of an archipelago and is famous for its active volcanoes and the related earthquakes, as well as tsunamis. It is his first visit to the island and he gives such information as context for his viewers. The island has beautiful mountains, forest, and sea and the people harvest fruit and vegetables and also catch fish and animals for everyday life.

Napaj drives a car and crosses a bridge to enter the island. As soon as he enters the island, he comes across a huge slogan saying “Empower and enrich our community by nuclear energy”. In the past, people on this island heavily depended on harvest by nature and developed a belief system worshipping the spirit of nature. He often stops by shrines and temples with beautiful representational ornaments. He continues driving the car and comes across another slogan saying, “Stop nuclear energy”. It seemed that the local residents must have put up such a slogan, but he doesn’t see anyone nearby.

He stops by a local restaurant for his lunch. He orders assorted slices of fresh fish. All the fishes are too rare and too expensive to have in major cities, and he shows off the variety of rare fishes and their freshness to the viewers. Even a local fisherman tells him that it is becoming more and more difficult to catch them, since the forest doesn’t hold raindrops in the soil because of the lumber industry and doesn’t drain good nutrients to the rivers and sea. And the local fishermen lose their jobs and become construction workers to make roads and public buildings by order from the local and the national governments.

After he finishes reporting his lunch, Napaj notices a TV in the restaurant showing footage of a big earthquake and the following tsunami, as well as the explosion of the nuclear plant. He recalls that it has been five years since the incident and nothing has been resolved. He thinks of his son and daughter. What kind of living conditions and natural environment can be passed down to them? He couldn’t think of a concrete solution for them, but was dared to challenge the issues with ideas and actions through his travels and findings.

He continues to drive his car to the west and comes across another slogan saying, “Abolish nuclear weapons! A town for peace”. He has gotten to know that there must have been several groups who have different values and perspectives for survival in the town. He looks for a local resident and finds a young woman with her daughter. Both are looking toward the sea.

The reporter (Napaj) : Hello. How are you? I am Napaj, a TV reporter from overseas. You don’t mind if I asked you a couple of questions?

A local woman: Hello, nice meeting you. Yes. I don’t mind. But I am not sure if I could correctly answer your question. Don’t you mind?

The reporter: Not at all. So, would you tell me a little bit about all those slogans about the nuclear plant and so on?

Local woman: Ah, yes. These were put in at different periods. The first one was put up about 30 years ago. People on this island didn’t have much benefit from economical development back then and also couldn’t continue farming and fishing for their livelihoods since the soil and water were affected by pollution from somewhere.

The reporter: That’s really sad… So, the first slogan, “Empower and enrich our community by nuclear energy” was put up about 30 years ago.

Local woman: Yes. I was also as young as my daughter here—about five years old—back then. I thought it was natural to believe that it was good thing.

The reporter: Then, how about another one, “Stop nuclear energy”?

Local woman: Ah, that was put up almost at the same time. I mean, local residents didn’t like the idea of putting dangerous energy nearby. But half the residents thought it was necessary for the people on this island to survive, since the national government and the electricity company agreed to give financial support to the local government… even for research…

The reporter: Research?

Local woman: Yes, money for research before actually beginning the construction. Tons of money was poured into this town… not sure who received the benefit… but this state of equilibrium continued over 30 years, until now.

The reporter: Also, the other slogan? “Abolish nuclear weapons! A town for peace”?

Local woman: Yeah. It was put up some time in the past. Do you remember? This country is the only country that has suffered from nuclear bombs? But people never thought that nuclear energy was as dangerous as the nuclear bomb… such a pity, don’t you think?

The reporter: I see. I see the whole story behind them now. I feel very sorry but I am glad that the landscape and the beautiful oceans remain well. Wasn’t it a good thing for you?

Local woman: I think so. I would think so. I just can’t say yes or no… to be honest. Can you see the rock formation at the tip of the pier?

The reporter: Ah, yes, I can see rocks piling up on top of each other and I can also see something man-made on it, but it looks collapsed… What is it?

Local woman: It is a gate made of stone. I am glad that you are from other part of the world. We believe that it is a secret gate to communicate with spirit of nature. You know, I am a bit scared when I see it collapsed… Have you heard of Shinto?

The reporter: I have heard of it but I don’t know what it is.

Local woman: Don’t worry. It is a bit too complicated to explain anyway. But don’t feel bad about it. Even we don’t know what it is exactly.

The reporter: O.K. I will study it later. And I really appreciate your time and your kindness.

Local woman: You are very welcome. Thank you very much for coming to this small island. I wish you continue a good travel and experience here. I want you to come back again, though!

The reporter: Yes, definitely. By the way, where else should I visit before going home?

Local woman: Maybe a hot spring? You know, this island is famous for its hot springs, I mean, famous for its volcanic activity, more precisely. Didn’t you pass by a hot spring public bath just right after crossing the bridge?

The reporter: A hot spring public bath? Do you recommend it?