There are two main legacies that define urban inequality in South Africa: housing and transport. Apartheid was not only a racial ideology. It was also a spatial planning ideology.

There are two main legacies that define urban inequality in South Africa: housing and transport. Apartheid was not only a racial ideology. It was also a spatial planning ideology.

Johannesburg’s development into a wealthy, white core of business and residential activity, with peripheral black dormitory townships, was a result of specific legislation and government action accountable only to white citizens. Black people were confined to houses in townships that had little economic value. Black townships were synonymous with urban poverty. These houses were far away from business activity and jobs. As population movement controls eroded in the late 1980s, informal settlements began to concentrate next to formal townships. The story of Johannesburg, the financial center of South Africa, can help understand how the struggle to build these connections defines the extent to which Johannesburg can be considered “just.”

The notion of a just city in Africa will have to accommodate the extent to which the hopes of earlier generations of social scientists and policy-makers for rural-led development on the continent have now been rendered moot by economic patterns that are both global and local. In Johannesburg, one of the most industrialized cities on the African continent has become a magnet for rural South Africans, and international migrants from other African countries. The primary infrastructural challenge is not only about identifying technical shortcomings or mere numbers of delivery. It is about generating the voice from below to demand that infrastructure reach those who need it most, and to ensure the political will to manage contentious distributional decisions about land and public finances.

I want to show why this is so difficult, and how, in order to make the decisions that are “just,” we need to first make sense of the history that lies behind those decisions.

To consider the meaning of a “just city” is not a new endeavor. Cities have been sites of struggle for as long as humans have realized advantages to living and working close together. But the gains to urban agglomeration are founded on major infrastructural needs. A fundamental role for government institutions in cities has been to provide the basic services and infrastructure such as water, sewers, roads, and trash collection, which are required for the health and opportunity of the people who live in cities. Building the infrastructure of a just city requires a consideration of the political relationships that underpin what might otherwise seem like a simple question of technical engineering.

Behind infrastructure lies the basic consideration of a just city: politics. And the stakes are always high. To those with easy access to land, services, and infrastructure, both health and economic opportunity are much easier to come by than to those who must navigate life in the city without basic services and economic infrastructure.

Often, proposals to address the severe strain on services and infrastructure that characterize the rapid urbanization process in the Global South fall into three not entirely distinct categories. (1) The state should provide through big, top-down plans; (2) the market should provide through privately-funded infrastructure that addresses business needs; (3) communities of urban residents should provide through self-help mechanisms because of failures of both the state and the market.

Though I have observed and participated in such debates in cities throughout Africa over the last 5 years as an urban planning professional and researcher, I am disheartened at how little the debate seems to be moving towards generating practical processes for achieving meaningful scale of delivery of services and infrastructure. This is especially alarming when one considers the persistent growth of inequality and exclusion in cities, which are the primary hope for improving health and economic outcomes.

In this essay I propose a basic barometer of just city-making that can help move beyond old debates that have resulted in benefits for a few and a persistent struggle for the many in African cities. In short, the extent to which a city is just will depend on the extent to which a city has the institutional mechanisms to effectively connect the state with both the market and ordinary residents.

The ballot is only democracy in its crudest form. A city that moves towards more “just” outcomes anticipates both conflict and collaboration with representative groups of various segments and interests of society. These social groupings express themselves not merely during periodic elections. Without effective connections between the state and residents, cities will struggle to have the information and political will to address their infrastructural requirements in order to access health and opportunity. Likewise, without effective connections between the state and the market, cities will find it difficult to create the conditions for privately sourced investments that address public needs.

We are faced with what is, in practice, an often confusing cycle: just processes will depend on just outcomes, and just outcomes will depend on just processes. Primarily, this means linking opportunities for expression of political will beyond the ballot box to policies concerning the distribution of resources for which the public can both advocate and hold authorities accountable.

When South Africa made the transition to parliamentary democracy in 1994, municipal government structures across the country were in flux. After the first elections, a delayed process of urbanization took flight. On the one hand, new migrants from rural areas heralded an explosion of informal settlements near black townships and in the traditional central business district. On the other hand, new inflows of private investment heralded an explosion of new shopping malls and corporate offices that sprawled northwards. Taken together, these two processes strained the existing infrastructural capacities of the city.

While talk of infrastructure often foregrounds considerations of engineering and construction, the changes brought on by population growth and private development highlighted considerations that were not technical, but political. The challenge of the past two decades has been to link hard infrastructural investments to pathways to economic opportunity for the poor majority still excluded from so many of the benefits of the city. In Johannesburg, a municipal government designed to serve only white residents, was progressively merged with neighboring municipalities to integrate overwhelmingly poor black townships with much more affluent and white areas. In the early 1990s, a semi-formal body known as the Metropolitan Chamber represented a possibility of constructing a post-Apartheid city that would highlight principles of equity. Some community groups, key NGOs, business leaders, and officials from all local municipalities in the Johannesburg region, all sat together to develop a participatory vision of possible spatial transformation of the city. While some community-based activists have complained to me that this institution was not wholly inclusive of all parties in the city, it did produce a plan that represented a significant integration of a city planned to exclude, especially through public transport and more inclusionary location of public housing.

By 2000, the city was formally amalgamated into a metropolitan municipality, which unified the tax bases of poor and rich areas. In interviews that I have conducted with private developers who work in different areas of the city, the overwhelming majority report next to no interaction with city authorities on planning matters prior to the amalgamation of five separate municipal authorities into the metro municipality in 2000. Likewise, city officials note that no spatial development framework existed for the city until 2003, and that spatial planning was more or less a dirty word up to that point, because spatial planning was the essence of Apartheid planning. A fiscal crisis in the city in 1997-98 led to a corporate reorganization of the city that ring fenced departmental budgets, which created a number of municipal-owned entities for electricity, trash, and roads. While this solved a short-term financial crunch, it meant that operational management of the city was increasingly fragmented.

Most significant is that grassroots organization has diminished in the past 20 years. Community-based activism was strong in Johannesburg in late 1980s and early 1990s, helping to bring down Apartheid through rent boycotts, strikes, and protests against illegitimate “local authorities” in black township areas. The civics movement, as the community-based activist groups were known, had joined hands with the trade union federation COSATU to form the United Democratic Front (UDF), the most significant part of the internal struggle to bring down Apartheid. When leaders of the ANC returned from exile, they resolved to dissolve the UDF. Civic movements and organizations, which had once comprised a large part of the UDF, struggled to survive as the new, democratically-elected government, led by the African National Congress, pledged to deliver what was essentially a technical fix: housing and services for all. It was difficult to organize without an obvious common enemy, especially when so much has been promised.

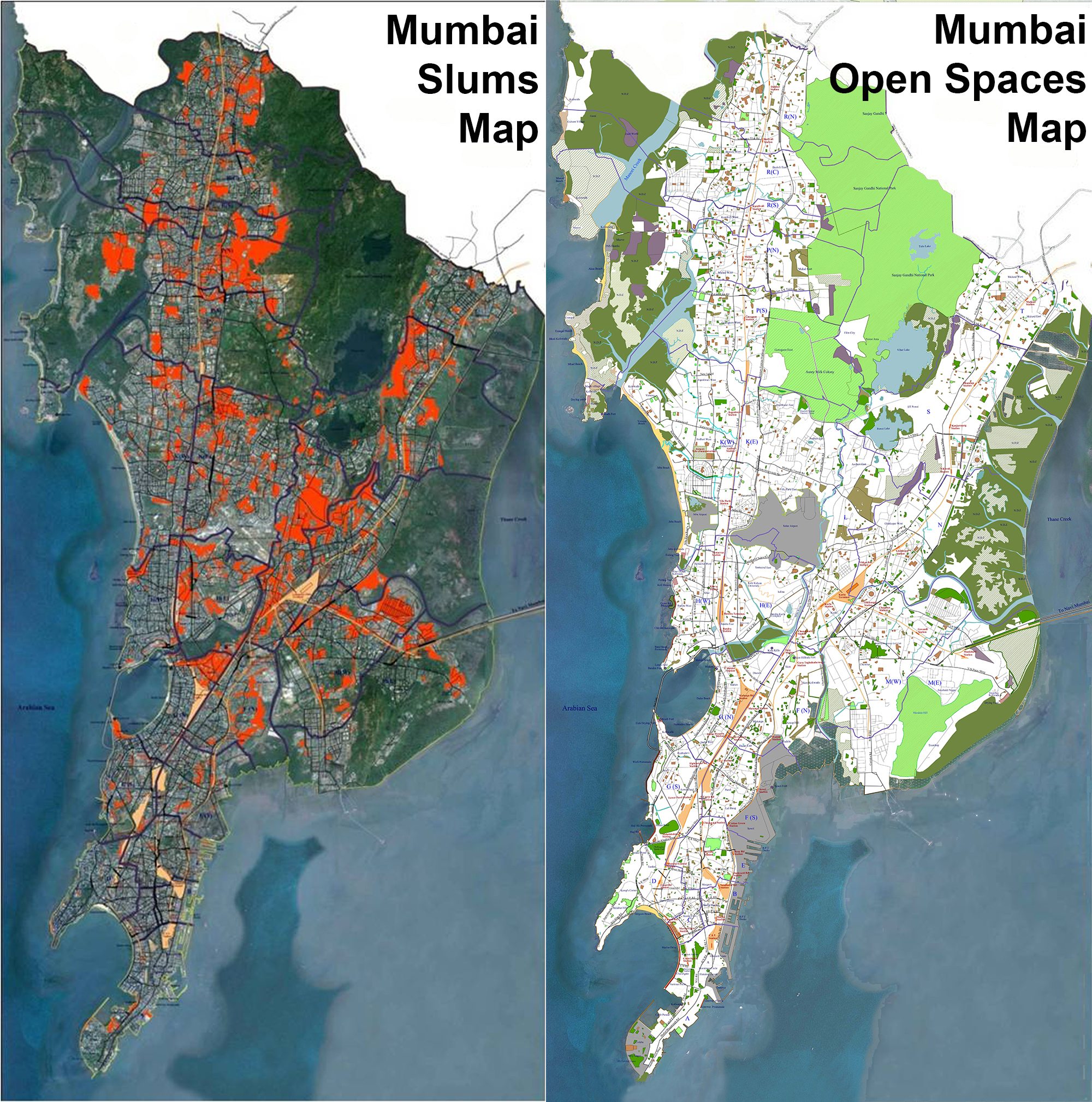

Yet, despite great success in terms of the technical scale of delivery, so much of post-Apartheid opportunity in Johannesburg remains linked to where one lives. The South African government has built over 2 million houses across the country in the past 21 years. But the scale of need in cities, especially in the fast growing urban centers like Johannesburg, has grown faster. There are an estimated 180 informal settlements in Johannesburg today. Moreover, the public housing investments that have been made, are primarily located far away from economic opportunity. Building large amounts of housing on cheap land makes it easier to achieve scale in delivery, but compounds the spatial legacies of Apartheid. Despite major public investments in basic infrastructure in township areas in Johannesburg, especially in the southern parts of the city like Soweto, only some retail development, and no major corporate development, has followed.

Absent effective state intervention or well-directed public investment in infrastructure, developers have told me that they sought cheap land, producing spatial change in the city that is uncoordinated and encourages single use. The sprawl northwards has stretched the bulk infrastructure of the city, which depresses the possible effects of significant public investment. The city has been unable to build or encourage more inclusionary precincts based on principles of mixed-use, high-density, and mixed housing.

The state, developers, and community organizations have progressively moved apart at the same time that only strong political will could have reduced the spatial gap that defines post-Apartheid inequality. Across the city, opportunity literally evades the poor by virtue of their distance from jobs.

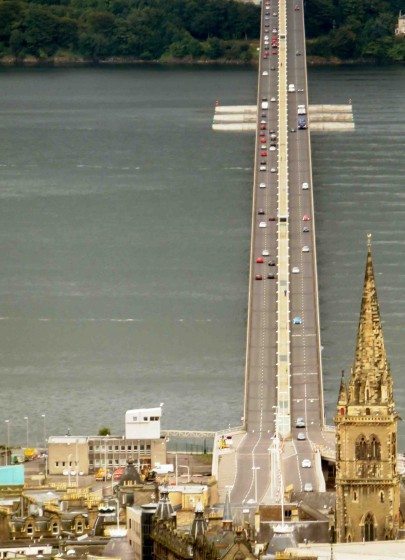

The current city government has plans for public transport-led development to stitch together the divided city. The mayor, Parks Tau, calls this plan the “Corridors of Freedom,” in which projects like a bus rapid transit system will make it cheaper and quicker for poor workers in township areas to reach their places of employment. The city plans to use its own land holdings and is buying up land around the corridors linking townships to business nodes. But it will be difficult for the city to reshape the property market along these corridors using only its existing land holdings. Tools to incentivize development, such as tax increment financing, and cross-subsidization of market-rate development for more affordable development are still embryonic. The uncertain political will to direct land and public finances toward a more equitable development trajectory remains at the heart of the urban infrastructure story of Johannesburg. It is difficult for civil society groups to coalesce around a citywide vision for inclusion in the city because of a historical institutional trajectory that has fragmented planning responsibilities and progressively shut down opportunities for public deliberation.

Johannesburg’s future prospects hinge on the same issues that define other rapidly urbanizing cities and city-regions on the continent. Indeed, the infrastructural deficits are even greater in most other major African metropolises than those in Johannesburg. Every city has its own particular stories and trajectories. Yet, there is a general thread that emerges from the experience in Johannesburg—especially for other rapidly urbanizing contexts—across Africa. These are contexts in which the demands for new infrastructure to accommodate new urban residents dovetail with severe inequalities due to historical legacies. In this sense, the challenge of urban development in African cities is to create the institutional spaces for deliberation and democracy that can enable civil society to articulate a vision of citywide change. This voice and this vision will be the basis of capable institutions of urban governance to actually deliver this change.

African urban futures are not wholly path-dependent. But technical fixes alone will not solve the highly consequential challenges of what is emerging as Africa’s first urban century. A half a century ago, people in many countries on the continent struggled for the end to colonial rule. Now there is a new basis of struggle for opportunity: urban space and infrastructure.

The gap between the slum and the gated villa is characteristic of African urban development today. This makes the deficit of “democratic infrastructure” a fundamental issue. Inclusion, equity, and justice, in Africa, will be defined by how social demands for infrastructure and spatial integration in the city are both articulated and realized.

Benjamin Bradlow

Boston

The Just City Essays is a joint project of The J. Max Bond Center, Next City and The Nature of Cities. © 2015 All rights are reserved.

I have lived in an array of fascinating cities, and visited a host of others. I have loved many (New York, Hong Kong, Harare and Berlin); been miserable in a few (London and Pretoria); oddly disappointed by some (San Francisco, Dublin and Sydney) overwhelmed by others (Shanghai and Cairo); and frankly terrified by at least two (Port Moresby and Lagos).

I have lived in an array of fascinating cities, and visited a host of others. I have loved many (New York, Hong Kong, Harare and Berlin); been miserable in a few (London and Pretoria); oddly disappointed by some (San Francisco, Dublin and Sydney) overwhelmed by others (Shanghai and Cairo); and frankly terrified by at least two (Port Moresby and Lagos).

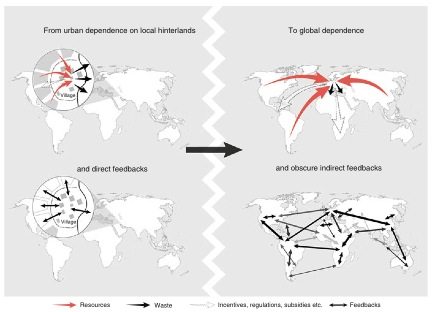

Since humans settled about 10,000 years ago, we have significantly altered and explored the landscape to create the civilization we now have. The landscape has been a source of material and non-material resources, feeding us in all senses. Ecologically rich landscapes associated with technologies were essential for all societies to emerge. The shape of landscapes along our history, have reflected how we produce our habitat and the goods that sustain us, our economies, and the way we live and relate to each other.

Since humans settled about 10,000 years ago, we have significantly altered and explored the landscape to create the civilization we now have. The landscape has been a source of material and non-material resources, feeding us in all senses. Ecologically rich landscapes associated with technologies were essential for all societies to emerge. The shape of landscapes along our history, have reflected how we produce our habitat and the goods that sustain us, our economies, and the way we live and relate to each other.

Try as you might, you’re no urbanite

Try as you might, you’re no urbanite

The birth of Paleo Cities

The birth of Paleo Cities

Resilience is the word of the decade, as sustainability was in previous decades. No doubt, our view of the kind and quality of cities we as societies want to build will continue to evolve and inspire new descriptive goals. Surely we have not lost our desire for sustainable cities, with ecological footprints we can afford, even though our focus has been on resilience, after what seems like a relentless drum beat of natural disasters around the world. The search for terms begs the question: what are the cities we want to create in the future? What is their nature? What are the cities in which we want to live? Certainly these cities are sustainable, since we want our cities to balance consumption and resources so that they can last into the future. Certainly they are resilient, so our cities are still in existence after the next 100-year storm, now due every few years. And yet…as we build this vision we know that cities must also be livable. Indeed, we must view livability as a third indispensible leg supporting the cities of our dreams: resilient + sustainable + livable.

Resilience is the word of the decade, as sustainability was in previous decades. No doubt, our view of the kind and quality of cities we as societies want to build will continue to evolve and inspire new descriptive goals. Surely we have not lost our desire for sustainable cities, with ecological footprints we can afford, even though our focus has been on resilience, after what seems like a relentless drum beat of natural disasters around the world. The search for terms begs the question: what are the cities we want to create in the future? What is their nature? What are the cities in which we want to live? Certainly these cities are sustainable, since we want our cities to balance consumption and resources so that they can last into the future. Certainly they are resilient, so our cities are still in existence after the next 100-year storm, now due every few years. And yet…as we build this vision we know that cities must also be livable. Indeed, we must view livability as a third indispensible leg supporting the cities of our dreams: resilient + sustainable + livable.

And so they are difficult to take in, both for their beauty and their complexity. How can you describe and assess them? Convey them to one who hasn’t seen? You finally stumble, awestruck, into saying that they are “beautiful,” or “majestic,” or just “amazing.” But all of us—as scientists, decision-makers, participating citizens—typically have to comprehend, describe and quantify such entities and then communicate the results in ways that aren’t hopelessly obscure—that are somehow specific and not just metaphorical. That is, we need to communicate a very complicated thing in a simple, essential and, above all, useful way.

And so they are difficult to take in, both for their beauty and their complexity. How can you describe and assess them? Convey them to one who hasn’t seen? You finally stumble, awestruck, into saying that they are “beautiful,” or “majestic,” or just “amazing.” But all of us—as scientists, decision-makers, participating citizens—typically have to comprehend, describe and quantify such entities and then communicate the results in ways that aren’t hopelessly obscure—that are somehow specific and not just metaphorical. That is, we need to communicate a very complicated thing in a simple, essential and, above all, useful way.

“We all know the sound of two hands clapping. But what is the sound of one hand clapping?” says a famous Zen Koan. At first consideration, it seems impossible to conjecture about the “just city” without having already in mind what is an “unjust city,” and vice versa. But my opinion is that this is wrong: It is possible to define what a “just city” is per se. To give flesh and substance to this essay I will focus on Paris and sustainability. First, because they are my fields of expertise, but also because sustainability and justice are two alleged priorities cited lavishly by the planners and elected officials to promote their urban policies. Their doxa considers that these two priorities are perfectly synergistic, but they are not. Planning for one may produce redlines in the other: sustainable policies often increase social injustice, as shown by Elizabeth Burton in a large sample of UK cities, or by Neil Smith when he denounces the veil thrown over profoundly unfair environmental dynamics that involve the departure of socially vulnerable people out of newly gentrified ecological neighborhoods. In fact sustainability and justice are like two rival brothers, and combining them in urban policies is certainly challenging.

“We all know the sound of two hands clapping. But what is the sound of one hand clapping?” says a famous Zen Koan. At first consideration, it seems impossible to conjecture about the “just city” without having already in mind what is an “unjust city,” and vice versa. But my opinion is that this is wrong: It is possible to define what a “just city” is per se. To give flesh and substance to this essay I will focus on Paris and sustainability. First, because they are my fields of expertise, but also because sustainability and justice are two alleged priorities cited lavishly by the planners and elected officials to promote their urban policies. Their doxa considers that these two priorities are perfectly synergistic, but they are not. Planning for one may produce redlines in the other: sustainable policies often increase social injustice, as shown by Elizabeth Burton in a large sample of UK cities, or by Neil Smith when he denounces the veil thrown over profoundly unfair environmental dynamics that involve the departure of socially vulnerable people out of newly gentrified ecological neighborhoods. In fact sustainability and justice are like two rival brothers, and combining them in urban policies is certainly challenging.

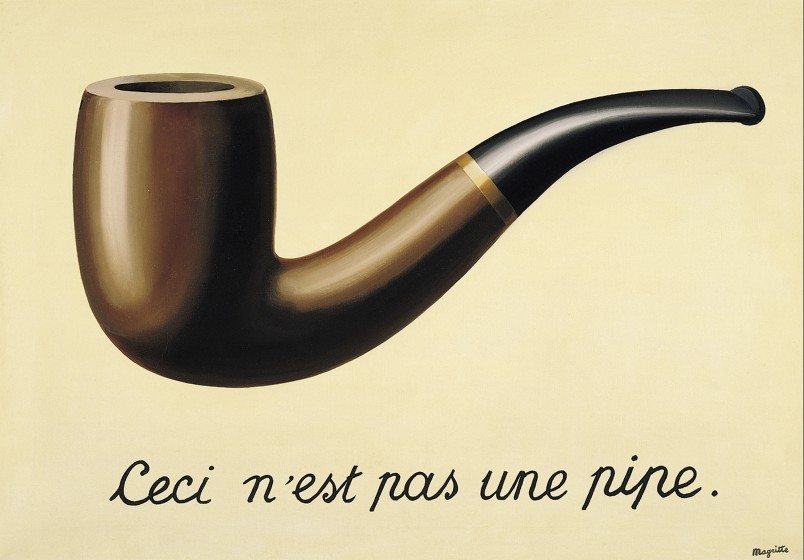

This means that fostering a just city is not about repairing previous mistakes to help people reduced to the status of “victims.” It is not about undoing what seems unjust. It never works. The expressions of injustice are exactly what they look like: expressions, representations, and symptoms that something has been going wrong. They are like the pipe in the famous painting of Magritte, called “The Treachery of Images.” It shows a pipe, and written under it are the words “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (This is not a pipe). This statement means that the painting itself is not a real pipe. You can’t smoke it. You can’t touch it. Similarly, the expressions of injustice are the result of complex dynamics. We cannot make things better only by opposing the expressions of injustice in the city. It would be like treating a disease only by addressing only the symptoms, or trying to smoke the pipe of Magritte.

This means that fostering a just city is not about repairing previous mistakes to help people reduced to the status of “victims.” It is not about undoing what seems unjust. It never works. The expressions of injustice are exactly what they look like: expressions, representations, and symptoms that something has been going wrong. They are like the pipe in the famous painting of Magritte, called “The Treachery of Images.” It shows a pipe, and written under it are the words “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (This is not a pipe). This statement means that the painting itself is not a real pipe. You can’t smoke it. You can’t touch it. Similarly, the expressions of injustice are the result of complex dynamics. We cannot make things better only by opposing the expressions of injustice in the city. It would be like treating a disease only by addressing only the symptoms, or trying to smoke the pipe of Magritte.

Once upon a time the city was called the “marvelous” one: Rio de Janeiro, cidade maravilhosa. Rio was the birthplace of samba, chorinho and bossa nova; internationally famous for supposedly being a city of fun and carnival 365 days a year, it has been the capital city of Brazilian proverbial optimism. Austrian novelist, playwright and biographer Stefan Zweig regarded it as the symbol and epitome of the whole of Brazil in his book Brazil, Land of the Future, published in 1941. Sure, it was as an idealization, some would say an ideological invention. After all, there were dictatorships (between 1937 and 1945 and again between 1964 and 1985) and their cortege of atrocities; there were huge socio-economic disparities; and so on. But the idea of a “marvelous city” seemed at least plausible. No ideology survives if there is not at least a grain of truth in it.

Once upon a time the city was called the “marvelous” one: Rio de Janeiro, cidade maravilhosa. Rio was the birthplace of samba, chorinho and bossa nova; internationally famous for supposedly being a city of fun and carnival 365 days a year, it has been the capital city of Brazilian proverbial optimism. Austrian novelist, playwright and biographer Stefan Zweig regarded it as the symbol and epitome of the whole of Brazil in his book Brazil, Land of the Future, published in 1941. Sure, it was as an idealization, some would say an ideological invention. After all, there were dictatorships (between 1937 and 1945 and again between 1964 and 1985) and their cortege of atrocities; there were huge socio-economic disparities; and so on. But the idea of a “marvelous city” seemed at least plausible. No ideology survives if there is not at least a grain of truth in it.

Through the lens of this meeting, it was evident once again, that Latin American cities share great similarities in their cultural heritage, development history, planning tradition, and social structure, offering big opportunities to share successful experiences for a sustainable future. Following this spirit during the symposium, the Latin-America chapter of SURE was launched in order to exchange information and expertise in the coming future. At this point, we are delighted to invite TNOC’s readers and writers interested in joining SURE to become members of the society, with a special invitation to those from Latin America. Our understanding of urban ecosystems is already emerging, but with little explanation of how these ecosystems function. A collaborative exchange will bring a better understanding, allowing cities to build a harmonious society with Nature.

Through the lens of this meeting, it was evident once again, that Latin American cities share great similarities in their cultural heritage, development history, planning tradition, and social structure, offering big opportunities to share successful experiences for a sustainable future. Following this spirit during the symposium, the Latin-America chapter of SURE was launched in order to exchange information and expertise in the coming future. At this point, we are delighted to invite TNOC’s readers and writers interested in joining SURE to become members of the society, with a special invitation to those from Latin America. Our understanding of urban ecosystems is already emerging, but with little explanation of how these ecosystems function. A collaborative exchange will bring a better understanding, allowing cities to build a harmonious society with Nature.

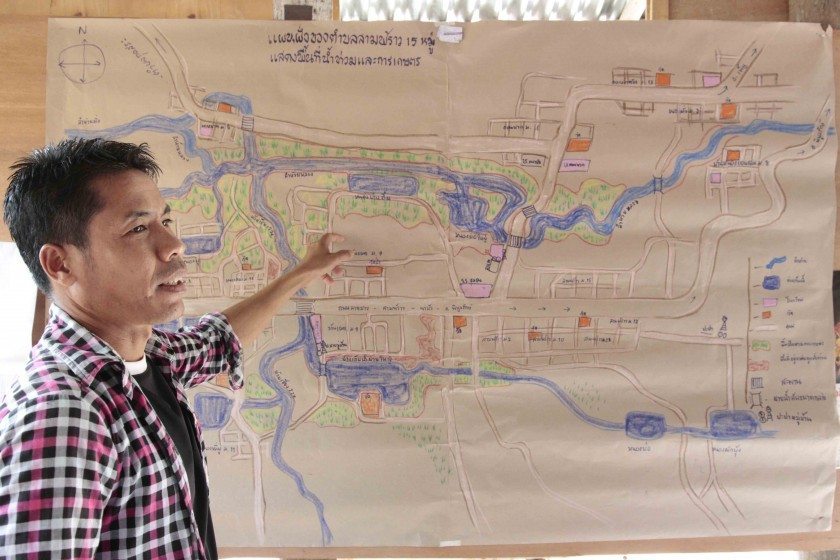

I believe that Urban Planning & Design (UP&D) should be considered a ‘Right’ and brought to public dialogue. The democratization of UP&D would be a significant step towards the achievement of just and equal cities. Exercising this right would be an effective means for bringing about much-needed socio-environmental change.

I believe that Urban Planning & Design (UP&D) should be considered a ‘Right’ and brought to public dialogue. The democratization of UP&D would be a significant step towards the achievement of just and equal cities. Exercising this right would be an effective means for bringing about much-needed socio-environmental change.

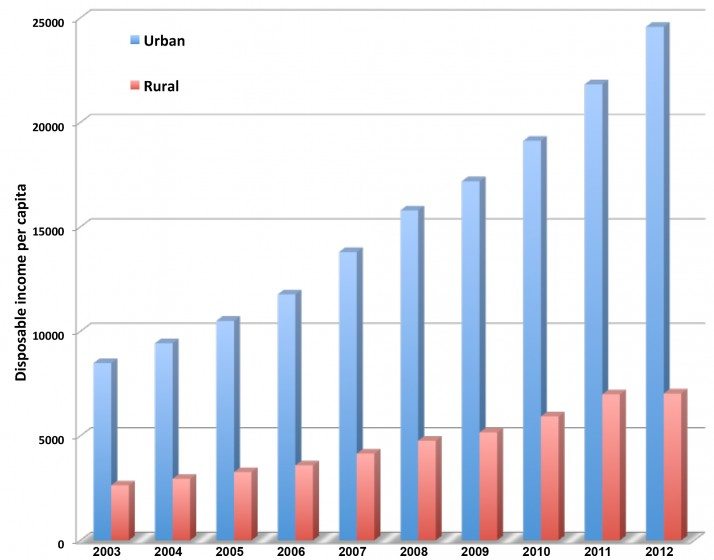

One of the root causes of inequity is urban and rural differentiation

One of the root causes of inequity is urban and rural differentiation

![In It Together[Image 02][Lokko]](https://www.thenatureofcities.com/TNOC/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/In-It-TogetherImage-02Lokko1-387x560.jpg) If I said earlier that no city piques the imagination quite like the African city, then I should also add that no city destabilises the idea of the ‘collective’ quite like Johannesburg. It is at once a city of anti-collectives and hyper-collectives; endless satellites of tightly-knit, tightly-policed enclaves that sit uneasily together, bound by a network of freeways, roads, taxi-routes and railway lines. For the most part, the enclaves remain intact, policed along class- rather than race-lines, although there are three or four pockets of genuinely mixed occupation (and here I invoke race not class) that have sprung up in the past decade. Within these enclaves, an exaggerated sense of community persists; an ‘us vs. them’ attitude where the terms are interchangeable—one man’s ‘us’ is another’s ‘them’, and so on. As a Jo’burger, the temptation to wallow in the city’s dystopian self-image is all too tempting. Disconnected, segregated, dysfunctional, dangerous . . . these are readily accessible, perniciously familiar tropes. Yet, thumbing through Sennett, it’s comforting (if that’s the right word) to recognise another truth: it was ever thus.

If I said earlier that no city piques the imagination quite like the African city, then I should also add that no city destabilises the idea of the ‘collective’ quite like Johannesburg. It is at once a city of anti-collectives and hyper-collectives; endless satellites of tightly-knit, tightly-policed enclaves that sit uneasily together, bound by a network of freeways, roads, taxi-routes and railway lines. For the most part, the enclaves remain intact, policed along class- rather than race-lines, although there are three or four pockets of genuinely mixed occupation (and here I invoke race not class) that have sprung up in the past decade. Within these enclaves, an exaggerated sense of community persists; an ‘us vs. them’ attitude where the terms are interchangeable—one man’s ‘us’ is another’s ‘them’, and so on. As a Jo’burger, the temptation to wallow in the city’s dystopian self-image is all too tempting. Disconnected, segregated, dysfunctional, dangerous . . . these are readily accessible, perniciously familiar tropes. Yet, thumbing through Sennett, it’s comforting (if that’s the right word) to recognise another truth: it was ever thus.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation