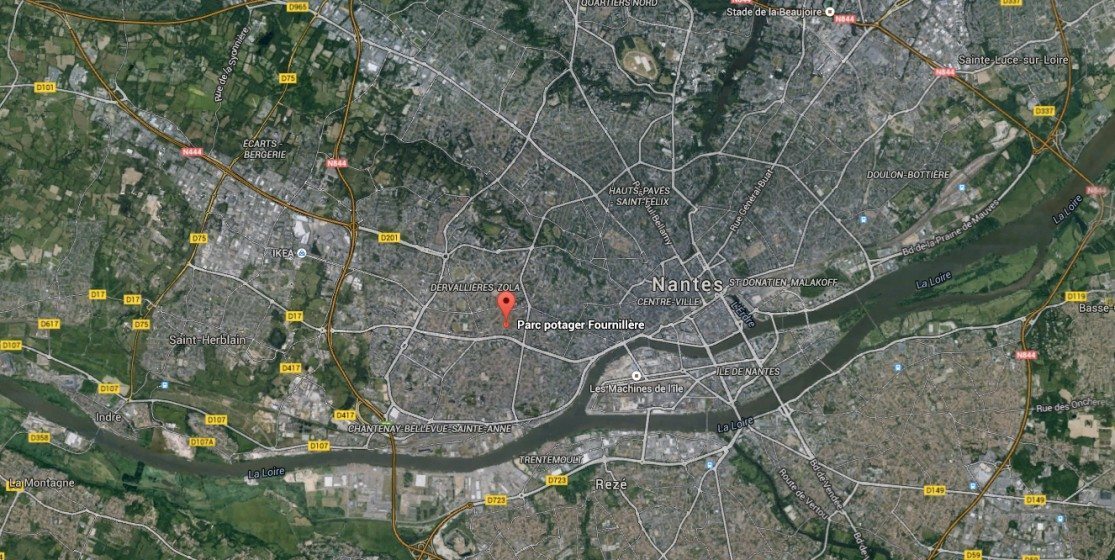

Earlier this year I had the good fortune to be invited to speak at a remarkable ‘Global Conference’ in Chantilly, France. The title of the session I was to contribute to was translated into English as ‘An urbanism built on a priority for fauna and flora’. This, it seems, was a slight mistranslation of ‘Un urbanisme construit sur une préséance du vivant’ but it suggested an emphasis in design and planning that struck me as being just what is needed if we are to have any hope of rolling back the massive damage that urbanisation has inflicted on the biosphere over the last few hundred years.

It fitted well with my contention of the last ten years or so, documented sketchily in my ‘Ecopolis’ book and mentioned in my first TNOC blog that the creation of ecological cities requires the development of Design Guidelines for Non-Human Species. In that blog my example was to suggest that an urban fractal or neighbourhood should be able to provide sufficient viable habitat that it can support at least one key indicator species of fauna and a majority of the species of birds indigenous to the place.

This blog further explores why we need these kinds of design guidelines, and at the bottom, makes some specific suggestions.

Cities are quintessentially human constructions, so it’s hardly surprising that reasons given for having ‘more nature in cities’ are almost invariably anthropocentric (think ‘nature-deficit disorder’ or biophilia). These reasons are typically to do with improving the quality of life for people, or even just their real estate values, but the bottom line for promoting urban nature is more profound; it is about human survival—without healthy natural environments our species cannot survive and cities make or break the natural environment. If cities fail to embrace nature in a demonstrably positive and sustaining way there can be little hope for the environment outside the city walls. Our reasons for valuing nature in cities needs to move beyond the ‘selfie’ view that puts a bit of greenery in the frame of urban portraiture and beyond the very reasonable proposition that integrating nature in our cities is good for livability, resilience, sustainability and human life generally. We need to simply accept that nature has needs of its own, and those needs may or may not be of benefit to human strands in the web of life.

This partly parallels ways of seeing the world found in a number of cultural forms, like Buddhism and Animism; it is close to the Daoist tradition in its acceptance of the natural world as ‘a self-generating, complex arrangement of elements that are continuously changing and interacting’ in which humans are a crucial component but one that should ‘follow the flow of nature’s rhythms’. It is specifically not about an enchanted view of nature and it is not about the worship of nature, not least because we are ultimately part of nature and any degree of self-reverence is dangerous.

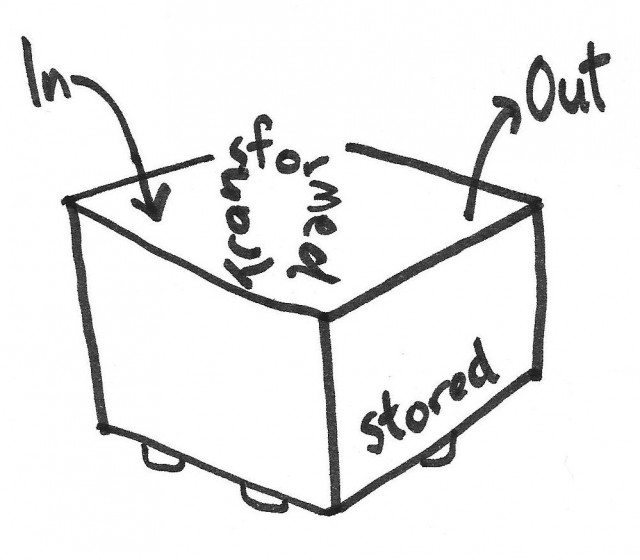

No, it’s simply accepting that for natural systems to function certain requirements have to be met and understanding that conditions and pre-conditions for the successful operation of biological processes are set by the nature of the systems and not by the predilections of the human animal. Where human activities affect those systems there are identifiable areas of contact and interaction where we need clear indications as to how to allow or support natural system (ecosystem) function.

Responsive it may be, but Nature does not negotiate

Nature is fractal. Each part of it is a microcosm of the larger whole. An urbanism that gave priority to the needs of nature and the requirements of non-human species would itself need to be fractal and support and nurture the essential functions of natural systems. To some degree it would need to be codified, just as we codify the expectations we have of our artificial human habitat, and that means establishing appropriate design guidelines, rules and regulations. If this agenda is to be taken seriously (and why shouldn’t it?), every city and town on Earth will need to develop such guidelines—to be acted upon as a result of both sensible persuasion (through the political process) and as a response to non-negotiable demands (of ecological necessity). Nature may be astonishingly responsive and receptive, but it does not negotiate.

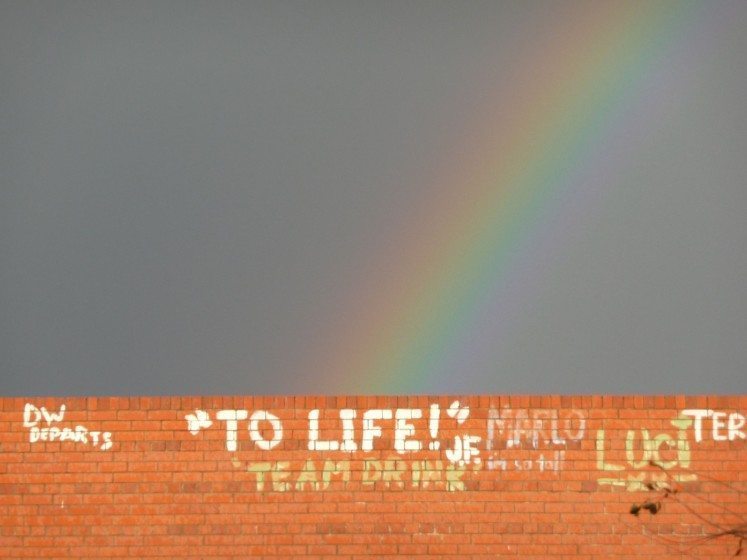

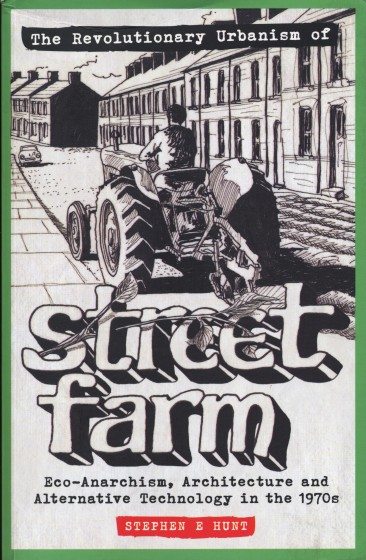

The rewards for human society of maintaining natural systems, apart from giving it additional capacity for long-term survival, includes the promise of a bold new urbanism, the aesthetics of which transcend the architectural fashions of the day and possess the gorgeous fractal messiness of nature—that messiness which confuses eyes and sensibilities trained by years of seeing orthogonal space and threatens minds crated up in cubicles, fed from cartons and boxed in by built environments. A radical urbanism, perhaps like that imagined by Street Farm over four decades ago as ‘alive rather than inert’, in which ‘a profusion of sprouting, breathing, photosynthesising, living things surround and entwine human dwellings’ (p.102 Stephen E Hunt in ‘The Revolutionary Urbanism of Street Farm’, Tangent Books, 2014).

The rewards for human society of maintaining natural systems, apart from giving it additional capacity for long-term survival, includes the promise of a bold new urbanism, the aesthetics of which transcend the architectural fashions of the day and possess the gorgeous fractal messiness of nature—that messiness which confuses eyes and sensibilities trained by years of seeing orthogonal space and threatens minds crated up in cubicles, fed from cartons and boxed in by built environments. A radical urbanism, perhaps like that imagined by Street Farm over four decades ago as ‘alive rather than inert’, in which ‘a profusion of sprouting, breathing, photosynthesising, living things surround and entwine human dwellings’ (p.102 Stephen E Hunt in ‘The Revolutionary Urbanism of Street Farm’, Tangent Books, 2014).

Notwithstanding the variants of ‘the ecocity idea’ that jostle for attention in the modern designer’s conceptual mind-scape, it is a fundamental tenet of ecological urbanism that urban areas and their associated infrastructure must shrink and relinquish their hold on the landscape to reverse habitat loss and fragmentation. An urbanism that prioritised fauna and flora would give over far less of the planet’s surface to cities and their paraphernalia. It would minimize the extent of roads and all the other concrete, tarmac and steel spaghetti of dead infrastructure in favour of space for the myriad creatures and vegetation that weave the living tapestry of the planet. An intensely ecological urbanism would distill the human presence into socially, culturally and politically rich, dynamic and diverse cities and towns; it would increase the constraints on how human society housed itself, but enrich and expand the world in which that society might thrive.

Birds, flowers, dirt and fire

There are a number of guidelines in place in cities around the world and numerous efforts to embrace nature in the planning and design of built environments, some of which are mentioned below. But my proposition is that such guidelines should be a requirement for every town, city and region.

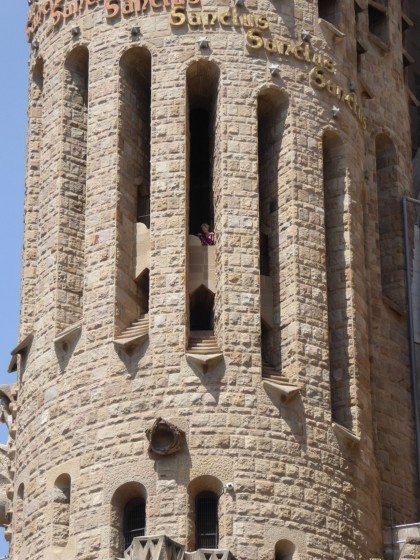

According to Andre Mader in his TNOC blog Peregrine Falcons have taken up residence in the Sagrada Familia. They love tall buildings and are the poster children of urban wilding, understandably so, but the successful reintroduction of fauna and flora into the urban environment will result in a lot of activity being out of the sight and awareness of most citizens and away from vidcams and tourist hotspots. Because of how we view and use media, if a city were to make itself falcon-friendly, for instance, and it worked, the chances are high that just one falcon pair taking up residence would be celebrated ad nauseam and the exercise would be celebrated as a success even if no other birds became city-dwellers. There needs to be a clear vision of what aspiring to be a city for nature really means. It has to move way beyond the tokenism of popular media and into an understanding that real life takes place whether or not it has a Facebook page.

Guidelines and regulation can be vital in protecting other species. Wind power is shaping up as a major source of energy and ecocities cannot reasonably be imagined or planned without it. The transition to an ecological society requires a move to renewable energy, but also requires that there be safeguards for natural systems in the process. Although far fewer birds are killed by wind turbines than are killed by flying into windows, the numbers can be minimised by not siting turbines in migration corridors. Accordingly, the American Bird Conservancy, which supports wind energy, has petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to protect migratory birds from the negative impacts of wind energy, asking for regulations to safeguard wildlife and reward responsible wind energy development. Such initiatives need to be a typical part of regional planning.

Vancouver provides a good example of what design guidelines for non-human species might look like in its Bird Friendly Design Guidelines Explanatory Note. The American Bird Conservancy publishes an excellent guide to bird-friendly design. Gaining even a passing familiarity with this document makes it hard to see how any architect or urban planner could condone the large expanses of glass on building façades that are known to kill between 100 million and one billion birds a year in the US alone. According to The Expanded Environment these guidelines have been adopted, edited and rewritten by several municipalities around the US and Canada, one presumes Vancouver is one of them. The facts and figures and known solutions are well established, yet glass boxes continue to be built. If we are serious about evolving our environments to be other-species friendly we must raise our game—and architects have to avoid deadly aesthetic fripperies like mirrored glass.

VicRoads, the transport agency of the state of Victoria in Australia, shows what design guidelines might look like when applied to road building with its Fauna Sensitive Road Design Guidelines (go to <https://www.vicroads.vic.gov.au> and search for ‘fauna sensitive road design guidelines’, which will automatically download).

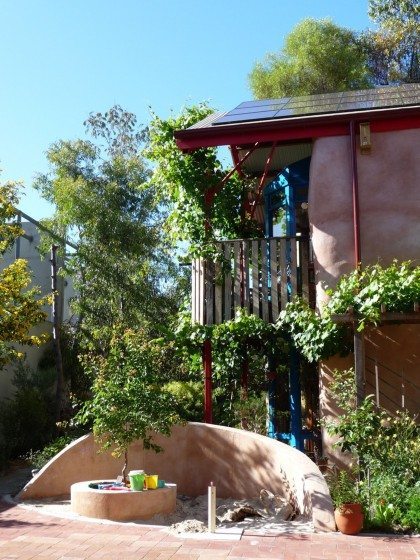

We might expect green walls and green roofs to feature prominently in a fauna-and-flora-friendly city, but if the design guidelines for non-human species were thorough, then the green roofs would have to be intensive, containing viable soil able to support micro-organisms and sequester carbon.

Wild flower meadows have been introduced in cities around the world and there are examples of ‘pieces of nature’ being encouraged as a direct intervention in existing urban fabrics. This requires an understanding of the appropriate conditions for these interventions. For example, to encourage wild flowers on the grasslands of Hampstead Heath, the City of London had to invert or remove existing soils made nutrient-rich by past agricultural practices.

A flower meadow has been created in the city of Melbourne. It’s not comprised of native vegetation but is, nevertheless, intended to increase biodiversity and represents a lower fire risk than native vegetation. Not all vegetation is created equal. In many parts of Australia people are encouraged to remove vegetation around houses in bushfire-prone areas although mown lawns are acceptable because they can help to reduce fire intensity. Planning for ‘wild’ green ‘open space’ may appear problematic in a landscape prone to wildfires, but if the totality of the urban/wild space system is an artificial construct in any case, it should be designed to incorporate fire management.

Aliens, domestication and buildings that create habitat

It can be difficult to pursue nativism in cities, but if Fred Pearce is right, it doesn’t matter too much whether the ecosystem that is brought into the urban system is ‘pure’ as long as it works. Allowing the inclusion of alien, i.e., non-indigenous, species in the mix makes the job of putting nature at the core of the city easier—though no less controversial to those who doubt the wisdom of embracing the wild as part of urban planning and design.

Creating built form that accommodates nature is not new; dovecotes, after all, have been around for centuries, although their purpose was not to provide bird habitat for its own sake, but to domesticate a source of food and fertiliser. The primary reason to accommodate fauna and flora in otherwise human environments has been to domesticate a species because it is useful for companionship, food, other products (e.g. dung) and services (e.g. guard duty).

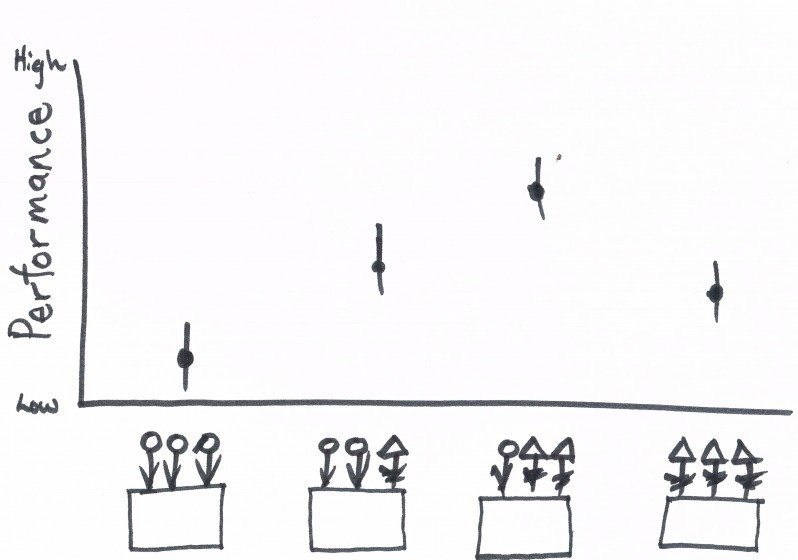

Some building rating tools, such as the Australian ‘Green Star’ building rating system give, credit for increases in potential habitat. The credit is a small part of the total green building assessment but is significant for its inclusion. This rating system is an extant example of tools that measure aspects of the built environment which relate directly to the welfare of non-human species. As such, it may inform the development of appropriate design guidelines.

A brief trawl of the Internet indicates that most design education has yet to respond significantly to the challenges nature is confronted with in sharing the world with people. One small exception is a two week design program in Norway titled ‘Designing for non-human clients’ that asked “How would you create a design if your client was a native wetland plant species? What are its wants, needs and desires, and how does it connect to the humans which utilize its services?”.

Thinking like an earthworm: communicating species’ requirements and restoring creeks and meadows

Designers may thus think in terms of briefs being provided by non-human clients and legislators may think in terms of consulting with representatives of non-human species. This idea goes back decades. John Seed’s influential 1988 book ‘Thinking Like a Mountain: Towards a Council of All Beings’ put forward the concept for representatives of non-human beings to be given an opportunity to put their views in a general council. This idea has been adopted by a number of groups over the years and, inspired by the concept, I trialled a version of it as an urban design workshop for children as part of the Whyalla EcoCity Development design program in South Australia, 1996. It was conceived of as a way to raise awareness of the needs of non-human species and to engage the community with its urban ecosystem through the design program of an ecocity project. Children adopted personas as various species—fauna and flora—ranging from earthworms to kangaroos and through the ‘Council’ voiced their concerns for their character’s environment. It was a way of discovering parameters for non-human species that could guide the design of an ecocity.

There are some wonderful examples of redeveloping bits of the city around the idea of ‘releasing nature’—such as creek restoration and the revival of meadowlands in city parks, but my proposition is simple. Rather than be content with a scatter-gun approach to reintroducing nature to our cities we should be seeking systematic ways of embedding the requirements for nature to flourish in, around and between every development in every city and town on the planet. Rather than being integrated as part of occasional special events, urban nature should be routinely integral to every planning process because nature requires it, not because of marketplace demands.

Pulling petals off a daisy and illiterate biomimicry

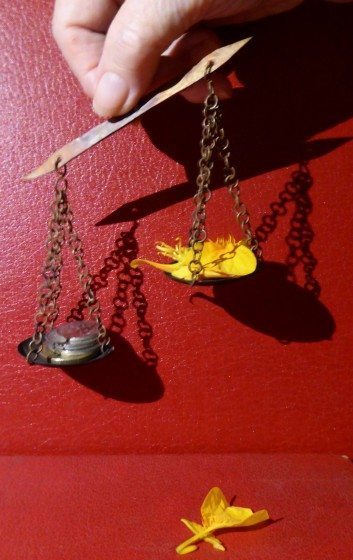

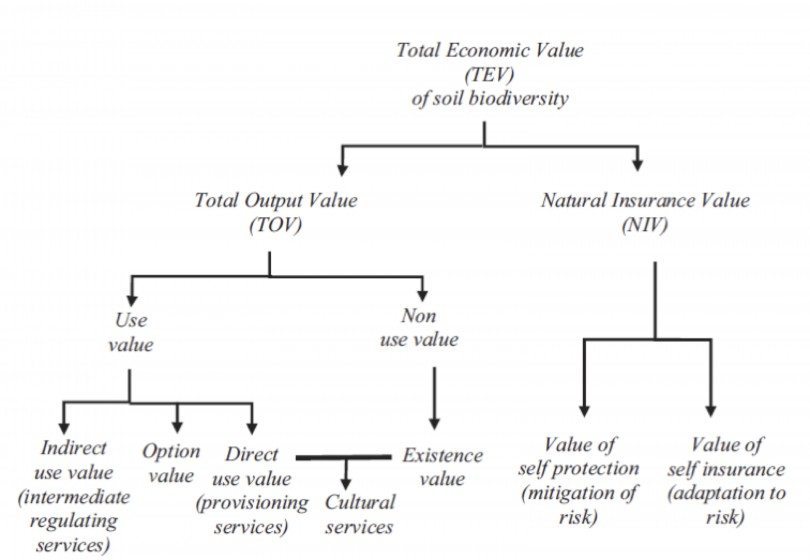

The commodification of nature is dangerous and devalues its real worth, as I argued in my TNOC blog of March 2013. Natural systems have to be recognised, formally and spontaneously, as having intrinsic value that trumps all other measures of their worth such as their capacity to provide ecosystem services, not because such services are not valuable in a real sense, but because the valuations being made are the result of pseudo-rationalist reductionism and amount to laying out the stem and petals of a daisy on an economist’s desk and claiming to have measured the worth of a flower.

Economic analyses of ecosystem services are inherently inadequate because they are unable to predict, and therefore measure and value, synergistic benefits that arise from those services. In the same way that reticulated sewage had impacts beyond healthier streets that could only be guessed at prior to its provision as a service, the synergistic benefits of natural systems are often unpredictable and not accounted for. Ecosystem services are valued in relation to a perception of their financial worth which depends on identifying the ‘service’ that’s provided. As a corollary, if a service isn’t, or can’t be identified, it will not, or cannot, be valued. This is the path to blind spots and selectivity based on partial knowledge. This pits butterflies against oak trees, slugs against daisies, worms against wolves. It presumes that nature can be assessed on a spreadsheet like a business, with profit and loss and monetary value overriding all other notions of value. There are those who say this is just a tool, a mechanism, a device for giving natural systems some value in a world that views all values in monetary terms, but that view is culture-bound to a particular world-view (consumer capitalist). It is one-eyed and reductionist—it is pulling petals off a daisy and then calling the pile of flower parts ‘more or less a daisy’.

There are two reasons for acknowledging the intrinsic value of natural systems: 1. because of its holistic beauty, 2. because no matter how hard we try we will never fully comprehend all the elements and their interactions in a natural system and can never be entirely sure that we do understand how it ‘works’.

In an era of accelerated climate change and ecological collapse it can be argued that many, if not all, natural systems are now so compromised and distorted by human intervention that their original intrinsic value and wholeness no longer hold—but that would be going down the slippery slope of pointless nihilism. As our tracks across the planet take us through ever more degraded landscapes, not only has nature dropped into the rear-view mirror, it is often behind the last bend in the road, invisible. If it ever does come into sight our children barely know how to describe it, as the language to describe nature is itself being lost in a world where authoritative publications such as the Oxford Junior Dictionary have decreed that words like ‘buttercup’ be usurped by ‘broadband’. The ability to see the world and understand what is being seen has to be practised and practiced. How can we develop biomimicry in a world where people don’t know the words to describe what they’re hoping to mimic?

Guidelines for not building

Effective design guidelines for non-human species may result in things not being built, or in them being demolished. As an example, recent research has established that 70 percent of remaining forest is within 1 km of the forest’s edge and subject to the degrading effects of fragmentation. Forest edges need to be retired. Considerably. If re-wilding advocates like George Monbiot are correct in their approach to wilderness restoration we will need to re-introduce species to regions that lost them hundreds, or even thousands of years ago. Some of these re-introductions may be by stand-in species when the original species has been made extinct—like the elephants that roamed Northern Europe and the British Isles.

For natural systems to operate optimally they generally need minimal human intervention. Restoring ecological health to the wilderness may require that it is maintained as wilderness, i.e. a place that is off-limits to most humans and their activities. Design guidelines for non-human species are likely to specify no-go zones. In order to thrive on this planet we need to occupy much less of it. The advent of virtual reality and the growth of vicarious experience through simulation may be increasing human alienation from the environment and from one another, but the upside may be that the perceived need to physically go into real wilderness will diminish, with positive consequences for real wilderness and the survival of a livable planet. Urban design guidelines for non-human species would almost certainly demand compact urban forms that released as much of the landscape as possible for non-human use.

Ecocity pioneer Paolo Soleri proposed cities of extreme density and zero sprawl, set in a more-or-less ‘undeveloped’ wild landscape. He may yet turn out to be prescient in this regard, along with the science fiction writers who described future cities like the dome enclaves in the movie version of Logan’s Run where the world outside the city walls had returned to wilderness and very few humans ever had cause to enter it. The domed city of Logan’s run was supposedly ecologically self-contained, an idea that has been visited a number of times in fiction. For example, in ‘This Other Eden’, inspired by Biosphere 2, Ben Elton takes the domed biosphere concept to one of its potential logically absurd conclusions as bespoke personal ecosystems where, as in Logan’s Run, the domes contain a closed ecosystem for humans to insulate them from a collapsing global ecosystem.

Buckminster Fuller was the pioneer of the modern domed city concept as something genuinely feasible when, in 1960, he proposed the first use of a dome to cover an entire city, or at least most of it, in his proposal for placing Manhattan under cover. Stretching from 62nd Street to 22nd, 1.6 km high and nearly 3 km across, his idea was that the dome would regulate the weather, reduce air pollution and make most of the existing air-conditioning systems in the city’s buildings redundant. Meanwhile, with similar ideas in mind Dubai is planning to build an entire city under a glass dome.

The idea of constructing sanctuaries that contain and protect biomes in microcosm, securing their survival against global environmental degradation, is almost noble. It is the concept of the zoo or giant greenhouse being able to act as a kind of insurance policy by providing a repository of species and natural environments under threat. The Eden Project in Cornwall, England, is a powerful and beautiful expression of this idea. The Eden Project also provides a vivid example of regenerative and transformative development, in which a built environment development has facilitated the restorative use of nature without pretending to restore exactly what was on the (heavily degraded) site in the past.

We know, however, that containing nature in order to protect it is very unlikely to work. Evidence from experiments such as Biosphere 2 suggests that containing nature successfully in entirely closed systems may be beyond our abilities, at least for the forseeable future. The project has demonstrated in detail how hard it is to bottle ecosystems and provides, if nothing else, a salutary lesson in how difficult it will be to establish habitats in space or on other planets. Putting aside the problems of livability and equity, containing humans is relatively easy (think prisons, walled cities…). The logical solution to retaining the integrity of the natural world into the future is not to try and package pieces of that world to protect them from larger environmental stresses, but to quarantine the human activities that are generating those stresses. Rather than incarcerate fragments of biosphere perhaps we should incarcerate the perpetrators of global damage within the walls of their primary engines of destruction, the city. This wouldn’t require domes so much as walls and policeable borders. It would be doable… except that urban systems are entirely interknit with the global biosphere, and without livability and equity in our cities we can kiss goodbye to any real hope of sustainability.

Conclusion

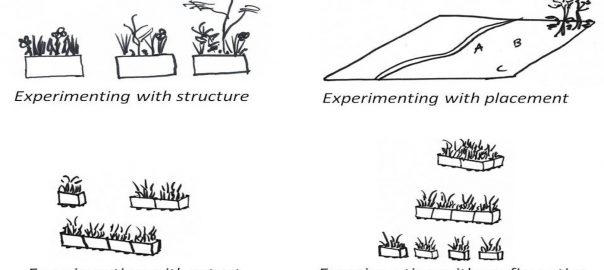

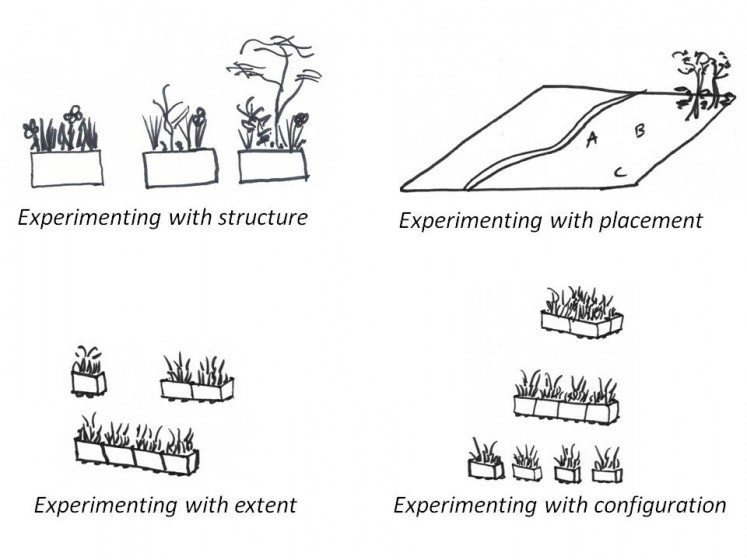

Guidelines can work at any scale, from city-wide to backyard, front garden, or apartment balcony, but may be most readily conceived and applied at the precinct or neighbourhood level where their influence on the larger urban system can, perhaps, be most effective—as a fractal of the system’s larger potential. Every city, every town and human settlement, should have a set of urban design guidelines for non-human species. The development and application of these guidelines would form the core of a new adventure in urbanism that has transformative potential and the capacity to lay the groundwork for a truly ecological civilisation—in which taking care of non-human species will, in turn, enhance the capabilities and conditions of the human animal.

Paul Downton

Adelaide

| SOME PRELIMINARY DESIGN GUIDELINES FOR URBAN NON-HUMANS | |

| PRINCIPLES (in no particular order) |

EXAMPLES (where identified) |

| The provision of healthy conditions for urban nature must be integral to every planning process | |

| Built environment development should create and maintain an infrastructure of green corridors within and between discrete projects and neighbourhoods | The Halifax EcoCity Project |

| Building rating tools and planning assessments should give credits for increases in potential habitat for non-human species | Green Building Council of Australia ‘Green Star’ ‘Land use and ecology’ credits |

| Built form, particularly at the level of individual buildings, precincts or neighbourhoods, should be designed specifically to accommodate nature and natural processes | Bridges designed for bats in Holland and Texas |

| All areas of vegetation be they parks, green walls or green roofs, should use substrates and soils that support the proliferation of healthy, ecologically healthy micro-organisms and sequester carbon | |

| All road building must follow fauna-sensitive design guidelines | VicRoads, Australia |

| Nothing should be built that damages the health of natural ecosystems | |

| Nothing should be built that damages the health of artificial ecosystems which support desirable urban non-human populations | |

| Consideration should be given to demolishing, removing or adjusting elements of the built environment that compromise the health of natural ecosystems | Creek restoration projects |

| Consideration should be given to demolishing, removing or adjusting elements of the built environment that compromise the health of artificial ecosystems which support desirable urban non-human populations | Creek restoration projects |

| Human spatial occupation of terrestrial, maritime and fresh water environments should be minimised to a level compatible with the achievement of a ‘one planet’ ecological footprint | Sonoma Mountain Village, California |

| A guiding principle of all urban development must be to minimise, and eventually eliminate, urban sprawl | |

| No-go zones should be instituted to limit human intrusion into natural ecosystems such as wilderness or near-wilderness areas | Wilderness Act (not quite ‘no-go’, but a start), USA 1964 |

| Restoration and creation of environments for urban non-humans should proceed in parallel and integrated with the building of human environments | Berlin – 44% of the city’s surface area is made up of woods, farmland, water, allotment gardens, parks and sports gardens |

| Wilderness restoration should be considered to re-introduce species to regions from which they have been lost in the recent or distant past. Some of these re-introductions may be by stand-in species when the original species has been made extinct | Efforts being made to reintroduce wolves, bears and lynxes to the UK |

| Compact urban forms should be favoured that accommodate humans but protect as much of the landscape as possible for non-human use | Green belts and urban growth boundaries |

| Existing urban non-human species should be identified and, where appropriate, sustained and protected | Cities around the world owe a lot to wildlife that is not always indigenous |

| Urban planning programs should consult widely and include a Council of All Beings, or similar, to raise awareness of the needs of urban non-humans and to engage the community with its urban ecosystem through the planning process | Whyalla EcoCity Development, South Australia 1996 |

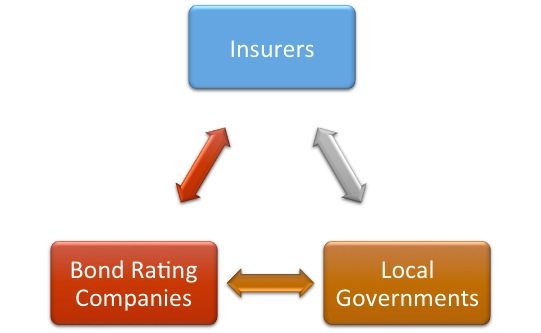

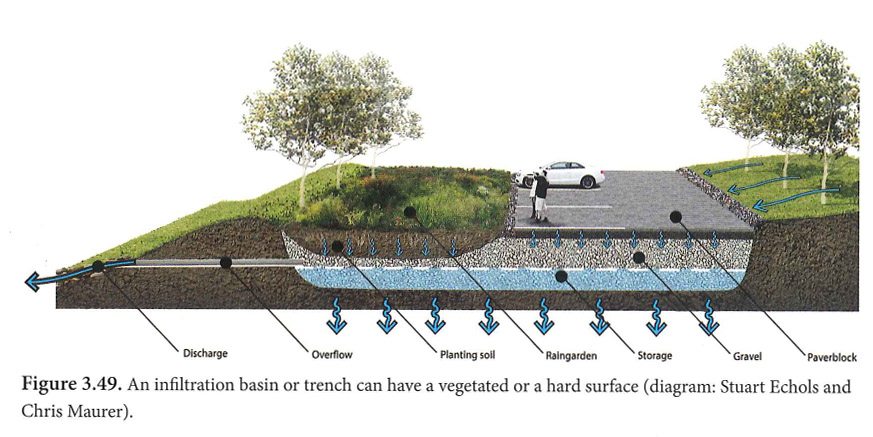

Nature-based solutions and urban ecosystems (through the services they can provide) mitigate some of these risks. So, it is logical to ask: if nature-based infrastructure — such as wetland buffers, storm water catching bioswales, etc. — are effective mitigations for ocean surges and storms, what is their insurance value?

Nature-based solutions and urban ecosystems (through the services they can provide) mitigate some of these risks. So, it is logical to ask: if nature-based infrastructure — such as wetland buffers, storm water catching bioswales, etc. — are effective mitigations for ocean surges and storms, what is their insurance value?

Stanford professor and Coursera co-founder Andrew Ng’s statement that “

Stanford professor and Coursera co-founder Andrew Ng’s statement that “

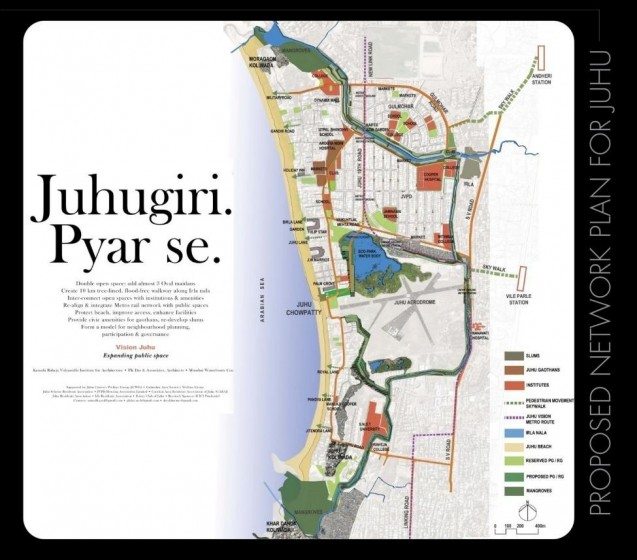

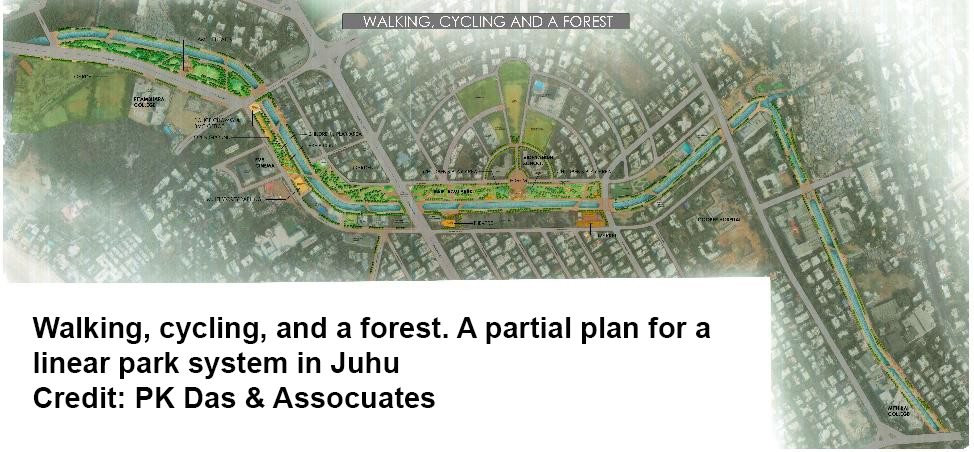

Through this plan we hope to generate dialogue between people, governments, and professionals and dialogue within movements working for social, cultural, and environmental change. It is a plan that redefines land use and development, placing people and community life at the centre of planning—not real estate and construction potential. A plan that redefines the ‘notion’ of open space to go beyond gardens and recreational grounds to include the vast, diverse natural assets of the city, including rivers, creeks, lakes, ponds, mangroves, wetlands, beaches, and the incredible seafronts. A plan that aims to create non-barricaded, non-exclusive, non-elitist spaces that provide access to all our citizens for leisure, relaxation, art, and cultural life. A plan that ensures open spaces are not only available, but are geographically and culturally integral to neighbourhoods and participatory community life.

Through this plan we hope to generate dialogue between people, governments, and professionals and dialogue within movements working for social, cultural, and environmental change. It is a plan that redefines land use and development, placing people and community life at the centre of planning—not real estate and construction potential. A plan that redefines the ‘notion’ of open space to go beyond gardens and recreational grounds to include the vast, diverse natural assets of the city, including rivers, creeks, lakes, ponds, mangroves, wetlands, beaches, and the incredible seafronts. A plan that aims to create non-barricaded, non-exclusive, non-elitist spaces that provide access to all our citizens for leisure, relaxation, art, and cultural life. A plan that ensures open spaces are not only available, but are geographically and culturally integral to neighbourhoods and participatory community life.

2 Comments

Join our conversation