Regularly, we feature a Global Roundtable in which a group of people respond to a specific question in The Nature of Cities.

Yunus Arikan is the Head of Global Policy and Advocacy at ICLEI, actively involved in leading ICLEI´s work at the United Nations, with intergovernmental agencies and at Multilevel Environmental Agreements.

Yunus Arikan

I was one of those who left Rio+20 disappointed with the rather vague language around Sustainable Development Goals. After following the debates over two years, it has become very clear that addressing “the elephant in the room” — to reach a global political consensus on the scope of universality of SDGs to be applicable to all levels (global, regional, national subnational, local), to all dimensions (social, economic, environmental, as well as peace and security) and to all generations (of today and tomorrow, which urges for planetary boundaries to be taken into account) — still needs a lot of trust and confidence building.

The good news is that there is a growing consensus that a stand-alone goal on sustainable cities and human settlements, or sustainable urbanization or an UrbanSDG, is needed for the challenge of universality of SDGs through its three key assets: reality, harmony, diversity.

Reality of an UrbanSDG refers to the fact that we are living in a new 21st Century Urban World. For the first time in the history of human civilization more than 1 out of the 2 people globally will be living in cities or urban agglomerations globally. It is inevitable that the success of any approach to global sustainability will rely how it is perceived by the urban population. Any service, product or management model needs to be transformed and evolved based on the economic relations, social and cultural dynamics and environmental impacts of the way they are produced and consumed in these urban settlements.

Harmony of an UrbanSDG refers to the fact that cities or urban agglomerations are complex living organisms. In the 1990s and 2000s, Local Agenda 21 enabled localization of the concept of sustainability worldwide. But in order to achieve a global transformation of sustainable communities, we need inclusive, well planned-managed, innovative and holistic “urban solutions”, rather than isolated, piecemeal, ad-hoc and temporary “sector-specific projects”. Harmonious solutions need to be cross-cutting. It does not make any sense to have smart buildings without public spaces, electric cars without renewable energies, economic growth without incorporating cultural values, waste management without locally grown food, public health without urban biodiversity, or implementation of impressive plans without an effective engagement and ownership of local communities that will be the main beneficiaries.

Diversity of an UrbanSDG refers to the fact that all nations, at the end, consist of a broad variety of cities and human settlements. Be it a small rural town in Africa, or a specific district in Europe, or a complex metropolitan area in America, or a diverse city-region in Asia, situated at coastal zones or mountain regions, in the heritages of the past or to-be-built settlements for the generations tomorrow, sustainable development has to address the sustainability of their populations within the local context. Global solutions can be tailored to accommodate the needs of each and every community.

Finally, it has to be noted that the success of the UrbanSDG depends on the way it is planned or governed within multiple spheres of government and their citizens. The world has moved forward tremendously since the context of “local authorities” was first introduced in Chapter 28 of Agenda 21 in 1992. Building upon the experience of over two decades of participatory processes of the Local Agenda 21 in thousands of communities worldwide, supported with their recognition and engagement in the agenda setting, policy development and implementation of the national, regional and global processes as “governmental stakeholders” and the urgency of direct, ambitious and collective action, enable local and subnational governments to be recalled as among the primary partners of the national governments, intergovernmental agencies and civil society.

Professor Genie Birch is the Lawrence C. Nussdorf Chair of Urban Research and Education, former Chair of the Board of Trustees for the Municipal Art Society of New York, and co-chair, UN-HABITAT's World Urban Campaign.

Genie Birch

Why is the United States government dragging its feet about whether to support a stand alone goal for cities and human settlements within the United Nations’ upcoming Framework for a Post 2015 Agenda when time is running out?

A bit of background will help you understand why I am asking this blunt question. A member-state driven effort, the final Framework will have 8-12 goals and associated targets that build on and replace the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) when they expire in 2015. The United Nations has appointed an Open Working Group (OWG), a 70 member/30 seat (vote), to develop the Framework. (The United States shares a seat with Canada and Israel.) This July, the OWG will present the Framework to the Secretary General for forwarding to the General Assembly in September. But the General Assembly will not vote on it until September 2015.

Despite this time lag, the hard decisions will be made in the next few weeks. This week, the OWG co-chairs promised to issue the Framework’s zero-draft around May 27. They also said that the current list of proposed goals still standing is too long. Over the past year, the OWG winnowed original list of 39 to the 16 still under consideration. Among the 16 is a proposal for a stand alone goal to “build inclusive, safe, sustainable cities and human settlements” with targets that cover urban planning, resilience preparedness, and the integration of housing, transportation and open space.

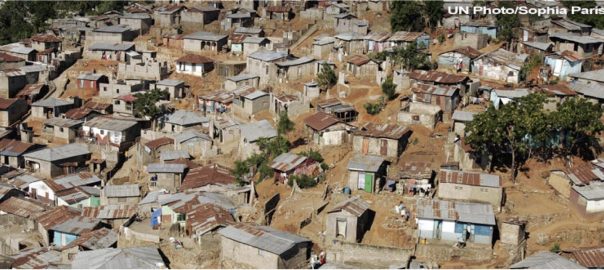

Remember, the predecessor framework, the MDGs, were the first-ever global consensus on development priorities. Experimental when first formulated at the turn of the 21st century, the MDGs were pioneering but not perfect. They largely ignored cities except for a nod to urban issues in a target for “achieving significant improvement in the lives of 100,000 million slum dwellers” as measured by the number of people living in slums. But this target, hastily constructed and added as an afterthought to Goal 7 — “To ensure environmental Sustainability” — was not only quickly met (and in fact, exceeded) but also proved essentially meaningless. By 2008, the world had more slum dwellers (1 billion) than in 2000 (760 billion).

Nonetheless, by its very existence among the list of targets, the slum metric stimulated a number of important efforts and offered key lessons for the upcoming Framework. First, it resulted in the creation of a definition of a slum dwelling as none existed before the MDGs. In 2003, UN-Habitat transformed this commonly used term into a measurable concept. (A slum dwelling lacks five qualities: access to improved water, access to improved sanitation facilities, sufficient-living area, not overcrowded, durable, structurally sound construction, and security of tenure. UN-Habitat further developed minimum standards for each quality.) Second, it stimulated a raft of innovative slum-upgrading techniques now practiced worldwide. Third, it showed today’s SDG framers that when it comes to sustainability in cities and human settlements paying attention to housing alone (even if the number is right) is insufficient. Needed is an integrated approach (participatory urban and regional planning) for providing a range of public goods (e.g. transportation, public space and housing) ensuring the efficient use of land to protect food supplies and ecosystem services and preparing for natural disasters. And these are the key elements of the proposed stand alone goal on cities and human settlements.

So this is why I posed the question at the beginning of this essay:

Why is the U.S. dragging its Feet on the Sustainable Cities and Human Settlements SDG?

Does our government lack recognition that the U.S. is 82% urban, the world is 51% urban and rapidly moving to 75% urban in the strongest megatrend of the 21st century? Does it still think we are living the Jeffersonian dream of an agriculture-driven economy? Does it really believe that a stand alone goal on cities and human settlements will really divide urban and rural interests irreparably as our US representative to the United Nations claimed last week? Does it really think that mainstreaming urban issues into other goals will substitute for the unique, spatial considerations and integrating functions that a city/human settlements goal will offer as our US representative asserted last week? The current U S position evokes three big questions among reasonable and thoughtful folks.

First, can’t our representatives read? The goal encompasses all human settlements. Rural people live in settlements that experience similar concerns as cities around housing, public goods/infrastructure and unmanaged growth but at a different scale than cities.

Second, does the U.S. government actually lack understanding of the inextricably linked fates of cities, peri-urban areas, suburbs, country villages, and farms in the 21st century? Cities are entirely dependent on the food-supplying and ecosystem services provided by non-urban areas. Rural places need access to city markets and services. Well-planned cities and regions will provide the foundation for achieving the expected sectoral goals on water, health, gender and food security.

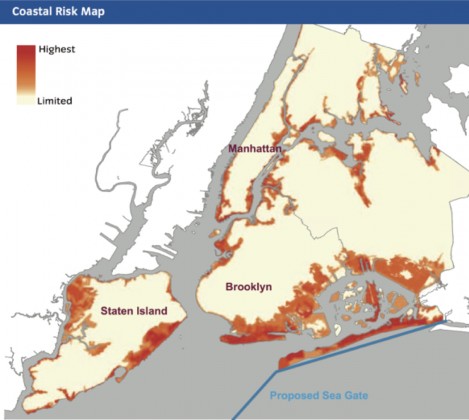

Third, does the U.S. government really think that the world can move the needle on sustainable development without paying attention to cities, currently the source of 80% of the world’s GDP (and, in the U.S., 70% of patents, the indicator of innovation) AND 80% of global greenhouse gas emissions? Does it really lack an appreciation of the fact that worldwide population growth rates are much lower than land conversion rates — this is a fancy way of saying aren’t our leaders aware of sprawl or unmanaged urban growth and how it damages the rural areas by gobbling up fertile farmland, fragmenting forests, wetlands and other important ecological assets along the way? Do they really think that the world can continue to allow people to settle in places vulnerable to natural disasters? (This last query stems from an observation that surely our representatives suffered with the rest of New Yorkers when Super Storm Sandy crippled the city in Fall 2012 — maybe they weren’t in residence then, but certainly they must read newspapers, watch newscasts or follow social media on these matters? And maybe they even welcomed HUD Secretary Shaun Donovan to New York as he oversaw the Rebuilding by Design project and dispensed billions in recovery funds.)

You may think that the U.S. stance is bordering on the unbelievable. And let me assure you, that while our representatives are publicly saying that they are open to either a stand alone goal or mainstreaming targets, they are positioning the mainstream option. I witnessed this performance last Wednesday when I attended the 11th meeting of the OWG in New York City. In her testimony on the cities/human settlements goal, our representative detailed the mainstreaming option while ignoring the stand alone. Earlier on, when testifying on the proposed infrastructure goal, she maneuvered to remove references to “rural” calling for its replacement by “vulnerable.” While no one can possibly object to helping the vulnerable, this U S sleight-of-hand-word-substitution tactic may be setting up a justification for the elimination of the cities and human settlements goal by saying its elements are covered in other rewritten goals. Watch out…

I think its time for us to encourage the U.S. government to pull up their collective socks and run fast to supporting a stand alone goal on sustainable cities and human settlements.

Benjamin Bradlow is a PhD student in the Department of Sociology at Brown University. His research investigates the role of urban politics and institutions in processes of democratization and redistribution in Brazil and South Africa.

Benjamin Bradlow

The development of the SDGs, and the prospect of an urban goal, are significant for all of us who work to make cities more inclusive. But much work is to be done, especially to ensure that an urban goal recognizes the deep divides of power, finance, and knowledge that characterize the decisions that drive urban development. SDI is one of a number of organizations that is demanding that the urban poor — the current losers but highest potential winners of such a debate — be located as central actors in the goals that governments and formal agencies adopt as the next development agenda. If we lose this opportunity, we will perpetuate a cycle of “development” that excludes so many and hides these failures behind empty rhetoric and cynical statistical tricks.

For the urban poor federations in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, that comprise our network, development goals are about improving the lives of real people. As such, a goal on cities must be fundamentally oriented around the people who stand to gain — or lose — the most from the success or failure of such a goal. This means focusing on the poor and especially the large informal housing and livelihood sectors that characterize our rapidly growing cities.

A target for universal provision of well-located land, shelter, and basic services should be a minimum of an urban goal. Unfortunately, the Millenium Development Goals included a goal on slums that was very unclear and very unambitious. An urban goal should encompass a specific focus on inclusion and the rights of the poor in cities through universal access to these amenities (land, services, shelter).

One of the biggest advantages of having an urban goal is that it focuses policy-makers on a specific space and a scale of administration in which to make change. In particular, this means a much greater focus on both formal local government and the constellation of actors that drive local governance. These are inextricably linked, and it is folly to think otherwise. Strong local government requires a strong and organized civil society to drive both innovation and accountability in our cities.

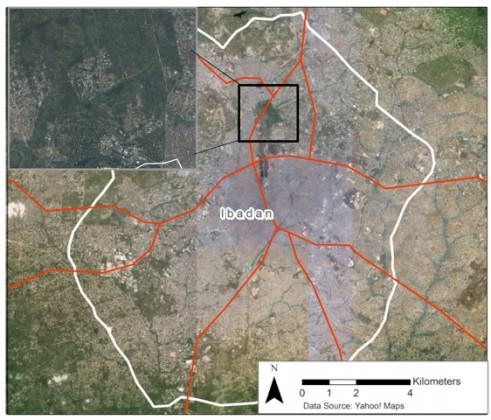

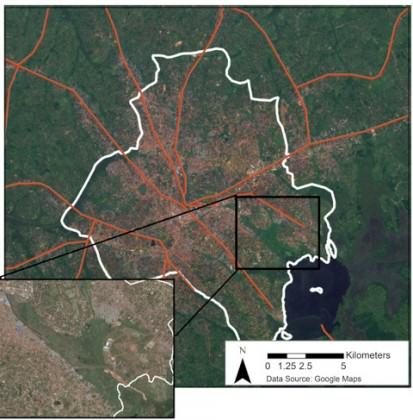

A fundamental competency of strong local government is to have universal data on all slums in their cities. Without this data, local governments pursue urban development projects and policies that are unrealistic and skewed towards wealthier, formal areas of the city. An urban goal should include provision for data collection on slums, underpinned by a commitment to data on 100% of all occupied land of the city (informal or formal). Such a goal should therefore stipulate the necessity for official inclusion, legitimation, and support for community-collected data on the nature and scale of poverty and informality in cities, especially by municipal authorities.

SDI’s experience is that data on informal settlements is most accurate and most comprehensive when it is collected by people who live in informal settlements utilizing people-centred, standardized survey and mapping tools. We have collected such data on almost 7,000 slums across the world, and currently SDI federations are collecting data in seven primary cities in Africa with 100% coverage of slums in those cities. These data are housed in a database that will go live later this year to manage such data on slums collected by SDI federations and many other groups and agencies.

We cannot ignore this debate because it will define our work for years to come. Now is the time to do what previous development agendas have conspicuously avoided doing: putting the voices and tools of the informal majority of our cities at the center how we work. This is the real promise of an urban goal in the SDGs.

Communitas Co-founder & Coordinator. Sustainable Development practitioner promoting socio-environmental justice & intergenerational solidarity for equitable communities

Maruxa Cardama

Communitas is the coalition for sustainable cities & regions in the SDGs, working as a task force of subnational and local practitioners to provide input to the SDGs process. Its core partners — Tellus Institute, ICLEI Local Governments for Sustainability, nrg4SD Network of Regional Governments for Sustainable Development and UN-Habitat — work in close collaboration with a multi-stakeholder advisory committee, with the support of the Ford Foundation and the Charles Léopold Mayer Foundation. Communitas’ vision is to capitalize on the interlinkages between sustainable human development, the eradication of poverty and inequality, and democratization that must and can be leveraged with sustainable urbanization processes.

The prevailing social, environmental and economic challenges that impact the quality of life in cities are multiple and interconnected. For Communitas, poverty, equality, human rights respect, governance and democratisation, and planetary boundaries conform the overarching framework within which to address critical concerns related to current urbanisation models around: sprawl and conversion of land; land tenure; balanced territorial development for the rural urban nexus; participatory planning; access to housing and public services; safety and social cohesion; community infrastructure; resilience and climate change adaptation; natural resources management and connectivity. All these critical concerns are calling loudly for a truly integrated approach to cities and human settlements by means, on the one hand, of a stand alone SDG; plus an adequate toolkit for implementation, on the other hand. Critical tools within the kit will be, for instance: policy strategies elaborated with an integrated and systemic approach; mechanisms for participatory decision-making; synergetic governance arrangements between different levels of government; adequate national budgets, as well as financing schemes directly accessible by subnational and local authorities; transparent multi-stakeholder partnerships; capacity building initiatives for local practitioners; disaggregated data, and grass roots data collection systems.

Communitas advocates for an SDG on Sustainable Cities and Human Settlements that aims for all new and existing cities and human settlements of all sizes to be inclusive, safe, prosperous and sustainable places where all members and their communities can thrive. Therefore, the Goal is neither to increase rates of urbanisation nor the quantity of new cities built.

In the context of the ongoing and increasingly political process for the negotiation of the SDGs, the Communitas Secretariat has recently released its second draft proposals for such an SDG. The proposal below must be read in conjunction with ongoing discussions at the UN intergovernmental Open Working Group on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs OWG); as well as with the Focus Areas Working Document released by the co-chairs of the Open Working Group on 17 April 2014. Communitas’ proposals will be refined as the political process changes gears in the coming weeks. However, by no means do nor will the proposed urban targets seek to exhaustively cover all aspects of a new paradigm for urban policy in the 21st century.

By 2030:

Target 1. Eliminate slum conditions everywhere and ensure universal access to affordable, equitable, and sustainable land, housing and basic services for all rural and urban dwellers.

Target 2. Increase capacity for participatory integrated urban planning and management to reduce urban sprawl, improve the efficiency in the management of naturalresources, and promote balanced territorial development for both rural and urban development.

Target 3. Ensure universal access to inclusive, safe and green public space for enhanced social cohesion, security of citizens and cultural & natural heritage protection and promotion.

Target 4. Strengthen resilience to climate change, man-made and natural disasters to reduce the loss of lives, assets, housing and infrastructure.

Target 5. Provide universal access to affordable, equitable, safe and sustainable urban and peri-urban transport for connected and healthy communities.

There are notable interlinkages with other so-called ‘Focus Areas’ of the UN Working Document released last 17 April. Strong considerations on poverty, prosperity and inequalities; health; economic growth and infrastructure; gender; climate; natural resources, ecosystems and biodiversity; respect of human rights; and governance and participatory democracy; are all incorporated in the proposals for a stand alone SDG outlined above. Water, health and energy improvements are both targets and outputs of sustainable cities and human settlements, which are fully addressed under separate ‘Focus Areas’ of the official UN Working Document.

More detail on the latest proposals by Communitas is available from

communitascoalition.org | [email protected] | @SDGcommunitas

Thomas Elmqvist is a professor in Natural Resource Management at Stockholm University and Theme Leader at the Stockholm Resilience Center. His research is on ecosystem services, land use change, natural disturbances and components of resilience including the role of social institutions.

Thomas Elmqvist

Since urbanization has the ability to transform the social and economic fabric of nations, and cities are responsible for the bulk of production and consumption worldwide, urban issues have to be at the heart of the Sustainable Development Goal Process. What would then an urban SDG look like? This has been intensively discussed at the UN Open Working Group meetings this spring and is a delicate and complex issue.

Many argue that an urban goal should centre around the sustainability of urbanization rather than sustainability of cities per se, and focus on the process rather than specific geographical locations. If we only address the city as a geographical bounded entity, we may end up with a set of targets and indicators addressing many important issues such as energy, waste, mobility, urban poverty, but we run the risk of completely missing how cities are influencing the biosphere and the potential local governments may have in developing effective resource management strategies. A focus on urbanization instead of cities, would have the advantage that crucial urban-rural interactions need to be considered and the long-distance effects of urbanization on resource extraction, energy, waste, etc. also would be included.

Such a goal may be formulated in rather general terms, e.g. by 2030 all local governments should have implemented policies for sustainable urbanization. However, to be effective such as goal must then be associated with a number of specific targets and indicators representing the operational mechanisms. For example, it would be possible to formulate targets and indicators that address to what extent local governments are putting policies and incentives in place (such as procurement measures) to ensure better stewardship of the all the distant ecosystems on which they depend. Furthermore, associated targets and indicators could be developed that capture the ratio between consumption and production of ecosystem services in the larger metropolitan landscape. Such targets and indicators would capture to what extent a city just may continue to be a large sink of consumption of ecosystem services or to what extent investments are made that reduce per capita consumption and investments done to increase production of ecosystem services.

To make this possible, scientists with urban and data expertise must actively support the technical discussions on selecting the SDG targets and indicators. If poorly defined and managed, targets and indicators will almost certainly have unintended consequences and negative outcomes that will be difficult to reverse.

In this context, silence from the urban scientific community may be the most dangerous path of all.

Mr Julian Goh has extensive experience in both the public and private sector in the area of urban planning and development. He is currently a Director at the Centre for Liveable Cities (CLC), which is part of Ministry of National Development Singapore.

Julian Goh

Cities today are home to over 50% of the world’s population, account for over 70% of greenhouse gas emissions, and yet generate 70% of the world’s wealth. And this growth will accelerate. We cannot hope to have a sustainable world without sustainable cities. The current set of SDG will kick in from 2015 to 2030. We need to focus on cities right now. Or we would have missed the boat.

A standalone Urban SDG will allow us to focus. With the right leadership, cities can mobilize and act much more quickly, compared to the national governments. We have seen how cities like New York, Copenhagen, Suzhou an Surabaya have moved much faster, adopted more ambitious sustainability goals, compared to their national governments. At the city level, we can focus, channel resources, execute, scale up and achieve results.

So what would an Urban SDG look like? We believe that it should try to encourage cities to achieve three inter-related outcomes:

1. A high quality of life which means a safe, healthy living environment with proper housing for everyone;

2. A competitive economy that can attract investments and provide jobs; and

3. A sustainable environment with clean air, water and land.

An Urban SDG can set development targets and performance indicators towards these three outcomes. In drawing up these targets, the Urban SDG would have to be mindful of the diverse contexts and circumstances of cities worldwide and therefore should be sensitive to their different abilities to respond to these targets.

Setting goals are useful. But it is even more critical for the Urban SDG to articulate how cities can achieve these goals. And to do this, we can take reference from some of the cities that have successfully transformed themselves. Let’s take 4 cities from 4 continents: New York, Bilbao, Medellín and Singapore. Each of these cities is different from the other in terms of history, political structure, geography, people, character and urban challenges. Despite these obvious differences and uniquely complex challenges can we find commonalities in their urban transformation experiences? The short answer is yes.

In a working paper titled “The CLC Liveability Framework in Global Practice” by the Centre for Liveable Cities (CLC), Singapore we have captured some of these commonalities. Three of the notable ones are:

1. These cities have a vision of what they would like to achieve

2. There is a comprehensive plan on how to achieve them and

3. There is institutional support to carry out these plans

Take Singapore for instance. Singapore started out as a fledging city of the 1960s plagued by much of the common developing city challenges such as high unemployment, urban slums, congested roads, lack of sanitation, pollution, etc. However, in a matter of 40-50 years Singapore transformed into a thriving global city. How did Singapore do it? The visionary leadership of the time drew up long-term cross sectoral development plans and supportive pragmatic policies which they effectively and efficiently executed with support of sound institutions. Bilbao is another example of a city that has taken the lead to address an adverse alteration of structural conditions. The 1980s saw major changes to the city’s economy resulting in wide spread unemployment, disenchantment and unrest. The city as a whole reacted and its acclaimed recovery transformed risk into opportunity and has put it on the international map. Such commonalities can also be found in the turnaround experience of New York and Medellín.

The world needs an Urban SDG. The Urban SDG needs to have goals, but even more importantly, it should shed light on the path to get to these goals. Cities play the central role for the world to achieve sustainable development. And the time to act is now.

Shuaib Lwasa is an Associate Professor in the Department of Geography at Makerere University. Shuaib has over 15 years of experience in university teaching and research working on interdisciplinary projects related to urban sustainability.

Shuaib Lwasa

Cities and human settlements are dominating the world in terms of consumption, resource use, innovation and creativity despite occupying only about 4% of the land surface globally. With over half the global population living in cities, this trend is likely to increase with current structure and path dependencies in Africa, which is urbanizing faster. Although many cities are demonstrating improved efficiency in resource use and began to work on efficient infrastructure systems, new cities will most likely follow the historical paths. This will have negative impacts of degrading environments, limiting economic opportunities, accentuating inefficiencies and affecting wellbeing. In view of current and possible future trends of urban development, a SDG focused on cites should be comprehensive enough to address the challenge of resource efficiency in cities and human settlements overall. Such a SDG goal would have to incorporate as focus areas minimization of resource use intensity, transformation of lifestyles, spatial reconfiguration and creation of economic opportunities.

A cities and human settlements SDG should have the following elements.

Urban lifestyles define the identities of individuals in cities and human settlements and have been associated with unsustainable resource consumption. Some of these lifestyles revolve around land use and transport systems. Sustainable urban systems will have to integrate land use activities with transportation with an aim of reducing trips and energy use. Likewise city-regional systems that would enhance utilization of local resources and minimize the ecological footprint where applicable would be necessary for sustainable cities and human settlements with a target of closing the loop.

Focus Areas under this element include: mixed densities in urban development, integrated planning or retrofitting urban activities with transportation, local economic development opportunities.

Resource minimization in cities and human settlements relate strongly with lifestyles and the spatial configuration of cities. Three linkages of resource flows to and from cities are described as: (a) Resources flow between cities and their hinterlands. Such flows can be in immediate hinterlands or rural environments; (b) Resources flow between cities and cities that are largely characterized by finished products or inputs into other production processes; and (c) the flow of resources between cities and other rural environments that are distant from the consuming cities. Often such flows can pass through other cities as conduits to the final destination. Minimization of intensive resource use in cities would have to directly develop strategies that reduce flows through substitution with locally available resources. Without putting a complete stop on current flows, creating incentives for use of city-regional resources in a sustainable manner is important.

Focus Areas for this may include: mining resources from shrinking cities, old cities or derelict areas, efficiency of in-city resource flows, waste-energy nexus, innovation in utilizing local resources including ecosystem services.

A SDG on cities and human settlements would be useful if upfront the design would create opportunities for all categories of urban dwellers. Current infrastructure systems, service systems in cities and human settlements are based on economics of profit maximization, which in turn limits opportunities for the urban poor. In many cities of developing regions, the urban poor are the majority and face the brunt of inequalities due to social, economic, environmental and political factors. Yet there are numerous micro-scale interventions (for example waster-to-energy, resource-based jobs, innovation in ICT) which have demonstrated possibilities for creating opportunities that can contribute towards improved wellbeing. A SDG on cities and human settlements requires harnessing the opportunities.

Focus Areas include: harnessing opportunities related to scalable resource efficiency, decentralized services and infrastructure, local employment and expanded markets, strategies that deal with urban poverty through livelihood opportunities.

Dr. Anjali Mahendra is an urban planner & transport policy expert working at interface of research & practice on issues dealing with cities, transport, climate change & economic development

Anjali Mahendra

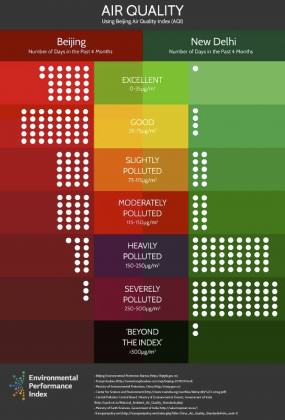

Here’s a statistic I like to use — combined, cities around the world occupy only 2% of land yet account for about 70% each of global GDP, energy consumption, and greenhouse gas emissions. This clearly shows how economic growth and resource consumption are inextricably linked and both are geographically concentrated in cities. With over half of the world’s population now being urban, cities are grappling with the heavy demand for urban services such as transport, energy, water and sanitation, housing, and solid waste management. In addition, the negative impacts of heavy resource consumption are manifested in poor air quality, dwindling water resources, deteriorating land and ecosystem resources, and public health impacts in cities, as well as climate and economic risks.

90% of the growth in urbanization comes from developing countries. These countries also face the maximum brunt of the above negative impacts because of a web of issues related to limited financing, limited government capacity, lack of data, lack of integrated urban planning, and governance issues, including high levels of corruption. These challenges are reflected in inadequate and unequal access to basic urban services in cities, particularly for the urban poor.

An urban SDG is an opportunity to mobilize all urban stakeholders — public, private, and civil society included — towards solving these issues. It would explicitly include targets for safeguarding basic rights to clean air, water, and housing for all urban dwellers, while preserving scarce resources like land and energy. It would include targets for the availability of safe drinking water and basic sanitation for all urban households, access to affordable housing, reduction of fossil fuel based energy consumption, reduction of urban air pollution, limits on the conversion of agricultural and ecologically sensitive land resources for urban development, and increased resilience of cities to the impacts of climate change.

Transport systems have become a major cause of traffic deaths, urban air pollution, lost economic productivity due to congestion, women’s safety issues, and decline in quality of life in many cities around the world. Therefore, targets for urban transport systems that reduce these externalities, improve conditions for vulnerable groups like pedestrians and cyclists, and increase safe, reliable mobility and access for everyone, must be part of an urban SDG.

Since transport improvements cannot be achieved without simultaneous consideration of land development, the urban SDG must also include targets to manage the rate of urban sprawl, conserve ecosystems in the face of increasing urban development, limit highly energy intensive forms of development, and use green technologies for improving and facilitating energy efficiency.

To achieve the above “physical” or infrastructure targets, several supporting targets related to governance must become part of the urban SDG. These include transparency of city level data, greater coordination across all levels of government with authority over urban jurisdictions, greater coordination across all urban sector agencies, accountability against performance measures (regarding how well cities are achieving the sustainability goals of environmental protection, economic development, and social equity), participation of all relevant stakeholder groups, and improvement in local governments’ technical and fiscal capacity.

These are some ideas on what an urban SDG should include. For more information, readers can look up an Issue Brief I wrote for the Communitas Coalition with some suggestions for targets to achieve universal access to urban services as part of an urban SDG.

Mary W. Rowe is an urbanist and civic entrepreneur. She currently lives in Toronto, Canada, the traditional territories of the Anishinabewaki, Huron-Wendat and Haudenosauneega Confederacy, and works with government, business and civil society organizations to strengthen the economic, social, cultural and environmental resilience of the city and its neighborhoods.

Mary Rowe

I am sure my fellow contributors will expertly advance all the reasonable, learned arguments for why we need one of the sustainable development goals the UN will embrace next year to be focused on cities and human settlements. Because the world is rapidly urbanizing so it’s where most people will ultimately live; because economies are driven by cities as is economic and social innovation; because the war on climate change will be won or lost in cities. These are all worthy points and I trust my colleagues have made them persuasively.

My reason is blunter. And it’s problematic. We need a sustainable development goal focused explicitly on cities, because national governments, without one, will continue their outdated, tired bias of setting national policies that ignore the particularity of cities and attempt to apply homogenous policies that incorporate rural, less dense and dense areas all together. National governments don’t think about cities. They think about national security, natural resources, economic imbalances, wealth redistribution. And they think about large systems like transportation, housing, and agriculture. We need a goal that specifies the challenges that cities around the world are facing, so that federal governments will be forced to look to the local conditions of the cities in their nations. Otherwise, urban needs just get piled into national objectives, buried there beneath provisions to equalize and treat fairly every community. But cities actually need to be treated differently, and urbanists (such as my colleagues here) will argue how.

In addition to needing a specific goal that ensures urban challenges are prioritized, we also need one to make clear that cities contain the solutions to their own challenges, and the role of federal and state/provincial governments is to enable that ingenuity, not proscribe uniform approaches. Again this poses challenges for federal governments that are attracted to one-size-fits-all grand gestures that ostensibly provide national consistency and dole out largesse ‘fairly’, but are so often unable to be customized to suit the specific particulars of each city. Further, cities are full of innovators, working at every level: neighborhoods, businesses, community leadership, local agencies and government. They are closest to their own community’s needs. Locals are the ones who know best what needs to happen to their housing stock, their parks, their schools, their shorelines. But federal governments, who generally control the lion’s share of fiscal resources, are loath to cede control, and tend to release resources often with provisos that constrain local innovation. An urban SDG has the potential to be sufficiently challenging that national governments will be compelled to delegate both responsibility and resources to cities to accomplish the targets and goals.

Constitutional and legal impediments in countries around the world have made empowering cities difficult, but cities that do enjoy higher degrees of autonomy (e.g. Singapore, Hong Kong) have demonstrated positive results. And in places where the hierarchy remains, there are repeated examples where city governments have found their own ‘work arounds’ — through pilots, unique partnerships with communities or the private sector — in areas of where their federal governments have jurisdiction. The truth is no matter where you live, the challenges to make cities more livable as they grow and more resilient as they evolve can’t wait for elaborate jurisdictional haggling. We just need to get on with it. Federal governments can continue to provide leadership, guarantee citizenship and set national living standards to which its members (states and cities) must comply. But we need leadership approaches that support granular innovation — housing or mobility solutions won’t be the same here in New York as they will be in Medellin or Mumbai. But we need the imprimatur of global leadership to press national governments to then empower local ones to harness the ingenuity of their on-the-ground partners and build sustainable cities. And an explicitly urban SDG will also make clearer the interdependence of cities and the hinterlands that surround them: they are inextricably linked, but needing differentiated policies and programs. Strong cities mean strong rural communities.

The problem may be that we’re expecting too much from nation states. We’re asking them to call out and explicitly support a political unit that they may perceive poses a threat to their own authority. (If and when the electoral boundaries are better aligned to reflect population distribution this may become moot: federal chambers will actually reflect where the majority of people are choosing to live …). But let’s strike an accurate balance: the world urbanizing is a good thing. It brings with it higher standards of living, better health outcomes, lower carbon emissions, and the creation of humanities great technological and cultural achievements. And healthy cities spell a better future for rural, pastoral landscapes to be preserved and not diminished, but valued and protected. Hopefully, an SDG focused on cities and human settlements will help the world recognize the reality of how the world’s people are choosing to live, and we can globally embrace a new narrative of sustainability, that is urban.

Andrew Rudd is the Urban Environment Officer for UN-Habitat’s Urban Planning & Design Branch in New York, where he leads substantive advocacy for the urban dimension of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (including the SDGs).

Andrew Rudd

I am writing from one of Fiji’s 332 islands where an urban SDG might seem like the furthest thing from my mind. Here my husband and I have found the perfect trifecta of being comfortable (including Wifi to email this piece) in a beautiful place with virtually no one else around. Our thatched overwater bure slips almost unnoticed between a coral-fringed beach and dense tropical forest and barely touches the earth on its pinpoint pilotis. At the same time, all of our fresh water comes from a hidden desalination plant, our uninterrupted electricity from a generator and our relatively mosquito-free evenings from regular fumigation. And we have brought with us the footprint of our (and countless other guests’) long-haul international flights. We hardly see one another. Yet, per person, our resource consumption and impact on the landscape are actually quite high.

I am trying not to feel too guilty about it, having just endured a brutal, vacationless New York winter in our one-bedroom apartment and on public transit. Sometimes we need a little luxury. Still, there is something fundamentally selfish about being simultaneously a part of everything and apart from it all. The more this becomes a way of life — e.g., as embodied in the classic American suburb, now being replicated the world over — the more we run up against planetary boundaries. If there is any hope for a sustainable future it lies in sharing the world’s resources better. But sharing is neither easy nor automatic. It is more than an abstract principle — it is about the very material reality of sharing space and resources.

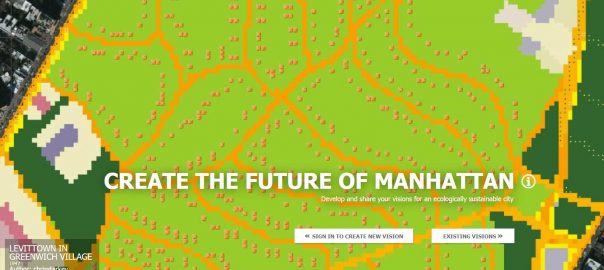

We need an urban SDG because cities are still the world’s preeminent sites for sharing. An urban SDG must therefore aim for the (re)configuration of all human settlements — megacities, metropolitan regions, intermediate cities, market town and rural villages, whether existing or still to be built — to enable and encourage more efficient and equitable sharing. As cities are poised to double in size over the duration of the SDGs — 2015-2030 — setting the stage now for how they grow is critical. An urban SDG must address that which other, more sectoral SDGs cannot. And it must focus on more than just infrastructure, which is fundamentally amoral about sharing.

Specifically, an urban SDG should promote sharing in three ways:

First, cities are consuming too much land at their peripheries. In so doing they are also forfeiting their traditional agglomeration advantages. Instead, they need to share space better with the communities and rural areas around them. An urban SDG should provide the aspiration for more compact cities that reduce sprawl and achieve balanced territorial development, and back this up by incentivizing national urban policies.

Second, within cities too much public and green space is disappearing and spontaneous development still proliferates. In short, too much land has been given over to private use. Those without means are forced to the margins, which are frequently unserviced and segregated by default. The public realm suffers. An urban SDG should set a minimum standard for urban planning and design that includes securing public space and protecting rights of way. As cities achieve this they will be more integrated, with safe public space and common infrastructure.

Third, many cities are dealing with massive infrastructural backlogs at the same time as they face increasing vulnerability to natural hazards. Cities are innovative and action-oriented, but they cannot face these enormous challenges alone. Costs and risks have to be better shared. An urban SDG needs to lever national and international support for big projects such as public transit systems and climate change adaptation measures that will improve connectivity and strengthen resilience.

It’s all about (re)configuring our cities for sharing. Otherwise we face a wasteful and boring world, if indeed we face a world at all.

Karen Seto is Professor of Geography and Urbanization at Yale. She is an expert on urbanization in China and India, forecasting urban growth, and climate change mitigation.

Karen Seto

The new era of urbanization involves a wide array of trends that can be described as either the biggest, fastest, or the first in history: the size and number of cities; the rate at which populations and ecosystems are urbanizing; the geographic shift from high-income to low and middle-income countries of large urban areas; the increased specialization of urban function; and the growing dominance of urban areas in national and global economic systems. The confluence of these characteristics presents both opportunities and challenges to the sustainability of Earth’s life support systems. Rather than arguing for any particular urban SDG, I propose that the United Nations consider at least three criteria in the discussions of an urban SDG.

First, urban SDGs should address the challenges and opportunities of urbanization that are beyond the scope of a single city or country. Such an SDG would need to address issues that would be achievable only if there were a global partnership.

Second, urban SDGs need to explicitly consider the aggregate impacts of urbanization on the supply and integrity of Earth’s life support systems. The focus here is on the aggregate impacts of urbanization on the global environment, and not just thinking about local environmental impacts.

Third, urban SDGs must be strongly linked with socio-economic development. Sustainable urbanization requires integrating economic development and human well-being explicitly, and includes elements such as human health and local livelihoods.

Lorena Zárate is co-coordinator of the Global Platform for the Right to the City and former president of the Habitat International Coaltion.

Lorena Zárate

Sustainable cities and human settlements — Building inclusive, equitable, democratic, safe and sustainable cities and human settlements

a) By 2020 guarantee universal access to adequate, well located, affordable and sustainable housing, security of tenure and essential services (potable water and sanitation, energy, telecommunications, waste recollection and management) for all, eliminating slum-like conditions everywhere and protecting and guaranteeing housing and land rights for all (including self-produced housing and neighborhoods, occupiers, renters, individual and collective owners, traditional and cooperative forms, etc.).

b) By 2015 end — without excuses — all forced evictions and displacements and guarantee proper consultation, compensation measures and remedies for affected people and communities, as established in the international human rights standard-setting instruments.

c) By 2020 guarantee the definition and application of negative social impact assessments at the community level and with inhabitants´ participation, especially in the case of megaprojects and “development”-related public and private investments.

d) By 2020 guarantee that at least 50% of the available public and private resources for housing and neighborhood improvement policies are dedicated to supporting community-driven processes of the social production of housing and habitat.

e) By 2020 guarantee universal access to safe, accessible and sustainable essential community public facilities and social services (schools; hospitals; markets; cultural, recreational and sport facilities; public spaces, and public transportation).

f) By 2020 considerably improve participatory, democratic and meaningful decision-making processes at the city and national level, guaranteeing proper representation of marginalized groups and those communities living under vulnerable conditions.

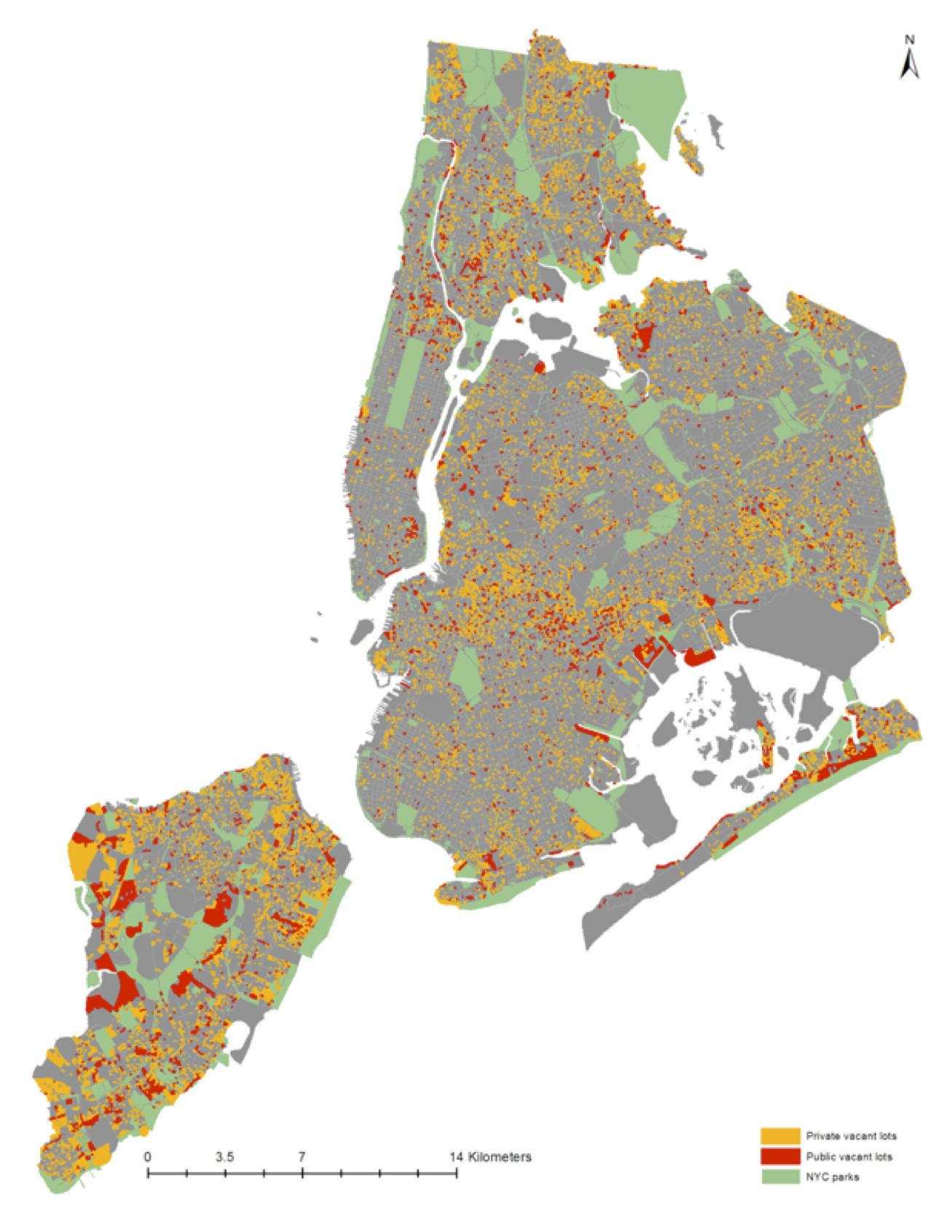

g) By 2020 guarantee the full implementation of the social function of land and property, designing public policies that inhibit land speculation and land grabbing (including parking lots!) and promote equitable and sustainable use of available land and the reuse of vacant buildings, in favor of social housing and community projects for homeless people and populations living in inadequate and poor-housing conditions.

h) By 2020 guarantee a productive habitat for all, with job and income-generation opportunities at the community level by promoting, protecting and supporting the social economy, with links to housing and neighborhood improvement policies.

i) By 2020 guarantee the democratic, responsible and sustainable use and management of the commons, including natural and energy resources, and avoiding exploitative relationships between urban and rural areas.

j) By 2020 guarantee the full protection and democratic, responsible and sustainable use and management of cultural (material and non-material) and natural heritage, as public and collective goods for present and future generations.

According to available studies, around 60% of the housing in Mexico has been built by the people. Similar percentages can be found in several countries of the Global South. The dualistic conceptualization of formal-informal does not captures the richness and diversity of these processes, and usually translates into limited governmental interventions and very often in its criminalization. We prefer to understand them as “social production of habitat”, a self-managed effort from communities and families to realize their right to housing and their right to the city. References: Among others, please refer to some of the following publications: Enrique Ortiz F. y Ma. Lorena Zárate (eds.), Vivitos y coleando. 40 años trabajando por el hábitat popular en América Latina, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana y HIC-AL, México, 2002; Enrique Ortiz Flores y Ma. Lorena Zárate (eds.), De la marginación a la ciudadanía: 38 casos de producción y gestión social del hábitat, Fundación Forum Universal de las Culturas, HIC y HIC-AL, Barcelona, 2005; y Rino Torres, La producción social de vivienda en México. Su importancia nacional y su impacto en la economía de los hogares pobres, HIC-AL, México, 2006.

According to available studies, around 60% of the housing in Mexico has been built by the people. Similar percentages can be found in several countries of the Global South. The dualistic conceptualization of formal-informal does not capture the richness and diversity of these processes, and usually translates into limited governmental interventions and very often in its criminalization. We prefer to understand them as “social production of habitat”, a self-managed effort from communities and families to realize their right to housing and their right to the city.

References: Among others, please refer to some of the following publications: Enrique Ortiz F. y Ma. Lorena Zárate (eds.), Vivitos y coleando. 40 años trabajando por el hábitat popular en América Latina, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana y HIC-AL, México, 2002; Enrique Ortiz Flores y Ma. Lorena Zárate (eds.), De la marginación a la ciudadanía: 38 casos de producción y gestión social del hábitat, Fundación Forum Universal de las Culturas, HIC y HIC-AL, Barcelona, 2005; y Rino Torres, La producción social de vivienda en México. Su importancia nacional y su impacto en la economía de los hogares pobres, HIC-AL, México, 2006.

Especially during the past decade, social housing policies have been in place in different regions of the world, thanks to a combination of financial resources from worker’s savings, public and private sector. The emergence of thousands of units overnight, usually located at more-than-one hour commute from the city centre, is conceived more like “plantations of houses” than as new towns or cities, with almost no planning for educational, health or commercial uses and with a very limited approach to public space. References: José Castillo, “After the Explosion”, in The Endless City, Phaidon Press Ltd., Londres, 2007, pp. 183-184.

Especially during the past decade, social housing policies have been in place in different regions of the world, thanks to a combination of financial resources from worker’s savings, public and private sector. The emergence of thousands of units overnight, usually located at more-than-one hour commute from the city centre, is conceived more like “plantations of houses” than as new towns or cities, with almost no planning for educational, health or commercial uses and with a very limited approach to public space.

References: José Castillo, “After the Explosion”, in The Endless City, Phaidon Press Ltd., Londres, 2007, pp. 183-184.

Policies affecting land and space are a key tool to reproduce or change the huge inequities affecting our societies. What real opportunities are we giving to the young people, vast majority of the population in many of our countries, if 85% of the new jobs are created in the so called “informal” economy? At the same time, not having a place to live, an address is also a denial of other economic, social, cultural and political rights (education, health, work, right to vote and participate, among many others). What kind of citizens and democracy are we producing in these apartheid cities? References: UN-Habitat. State of the World’s Cities 2010-2011, Bridging the Urban Divide, Earthscan, London, 2008. Electronic version available at http://www.unhabitat.org/pmss/listItemDetails.aspx?publicationID=2917.

Policies affecting land and space are a key tool to reproduce or change the huge inequities affecting our societies. What real opportunities are we giving to the young people, vast majority of the population in many of our countries, if 85% of the new jobs are created in the so called “informal” economy? At the same time, not having a place to live, an address is also a denial of other economic, social, cultural and political rights (education, health, work, right to vote and participate, among many others). What kind of citizens and democracy are we producing in these apartheid cities?

References: UN-Habitat. State of the World’s Cities 2010-2011, Bridging the Urban Divide, Earthscan, London, 2008. Electronic version available at http://www.unhabitat.org/pmss/listItemDetails.aspx?publicationID=2917.

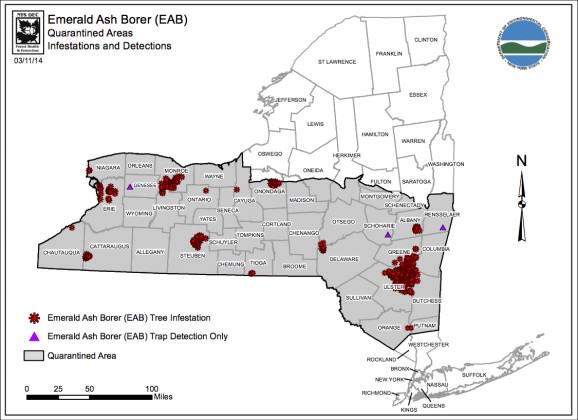

New York City (NYC) is an epicenter for invasive species in the U.S. and functions as a major pathway for invasive species to the rest of the continent. One of the challenges we have in managing urban ecosystems is dealing with the wide variety of exotics, including their ecological interactions and feedbacks. Natural resource managers in the NYC region have to worry about Asian longhorn beetle, Emerald ash borer, Hemlock wooly adelgid, and many other insects pests, in additional to a wide range of aquatic (zebra mussels, water chestnut) and terrestrial (kudzu vines) exotic invasives. Chestnut blight wiped out American chestnut populations — more than 9 million acres of American chestnut forest from Mississippi to Maine. Ash trees, which are common in towns and cities, as well as in backyards of homeowners, are likely to experience the same fate from the Emerald ash borer (EAB). This beetle has killed 50 million ash trees in Michigan alone since 2002 and it is closing in on New York City. Unlike chestnut blight, EAB will probably end up killing off 20 different species of ash trees. As Ash trees start dying, removing the dead trees before they fall and cause property and other damage will be financially costly for municipalities and homeowners. The USDA Forest Service has estimated the emerald ash borer will cost communities in a 25-state area as much as $10.7 billion by 2020. In New York City, forested areas include 900 million ash trees, approximately 10% of the total NYC urban forest.

New York City (NYC) is an epicenter for invasive species in the U.S. and functions as a major pathway for invasive species to the rest of the continent. One of the challenges we have in managing urban ecosystems is dealing with the wide variety of exotics, including their ecological interactions and feedbacks. Natural resource managers in the NYC region have to worry about Asian longhorn beetle, Emerald ash borer, Hemlock wooly adelgid, and many other insects pests, in additional to a wide range of aquatic (zebra mussels, water chestnut) and terrestrial (kudzu vines) exotic invasives. Chestnut blight wiped out American chestnut populations — more than 9 million acres of American chestnut forest from Mississippi to Maine. Ash trees, which are common in towns and cities, as well as in backyards of homeowners, are likely to experience the same fate from the Emerald ash borer (EAB). This beetle has killed 50 million ash trees in Michigan alone since 2002 and it is closing in on New York City. Unlike chestnut blight, EAB will probably end up killing off 20 different species of ash trees. As Ash trees start dying, removing the dead trees before they fall and cause property and other damage will be financially costly for municipalities and homeowners. The USDA Forest Service has estimated the emerald ash borer will cost communities in a 25-state area as much as $10.7 billion by 2020. In New York City, forested areas include 900 million ash trees, approximately 10% of the total NYC urban forest.

It took a few days of clothesline- and bird-watching to solve the mystery of the pellets in his pockets. Among the various wild creatures who shared Will’s yard was a Scrub Jay, a consummate city slicker of the not-so-wild American West. This bird, like so many of its Corvid cousins in cities all over the world, is a generalist and opportunist with a not too picky appetite for the veritable smorgasbord served up by us, both purposefully through bird feeders and wastefully when we throw out food and organic garbage. Dog and cat food make for delightful morsels for these omnivores, and it didn’t take long for my friend to notice that his Scrub Jay neighbor regularly pilfered the pellets out of his dog’s bowl on the porch.

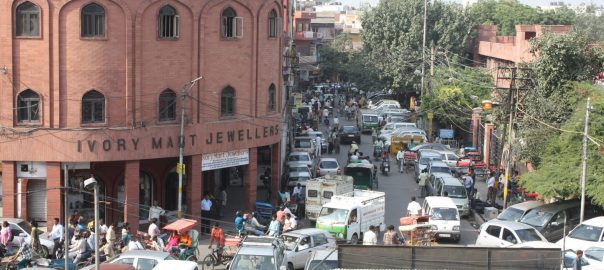

It took a few days of clothesline- and bird-watching to solve the mystery of the pellets in his pockets. Among the various wild creatures who shared Will’s yard was a Scrub Jay, a consummate city slicker of the not-so-wild American West. This bird, like so many of its Corvid cousins in cities all over the world, is a generalist and opportunist with a not too picky appetite for the veritable smorgasbord served up by us, both purposefully through bird feeders and wastefully when we throw out food and organic garbage. Dog and cat food make for delightful morsels for these omnivores, and it didn’t take long for my friend to notice that his Scrub Jay neighbor regularly pilfered the pellets out of his dog’s bowl on the porch. So what is the ecological rhythm of life in the city, for species that share our urban spaces with us? Dr. Ajith Kumar, one of my professors at the Wildlife Institute of India, while teaching us the methods of documenting and measuring primate behavior in the wild, made the observation that the daily time-budget and diet of monkeys—Bonnet Macaques—in Chennai (and other South Indian cities) consist of hanging around people’s kitchens and eating idli (steamed rice-and-lentil cakes) for breakfast. Just like the human inhabitants of those cities. Nearby, House Crows watch people keenly and dart into kitchens through open windows in sudden snack attacks that startle the human inhabitants but seldom draw more than a frustrated yell or an expertly dodged broom thrown in retaliation. Like their Scrub Jay cousins in California, and other corvids around the world, these Chennai residents have figured out when and where to obtain food reliably in the urban maze.

So what is the ecological rhythm of life in the city, for species that share our urban spaces with us? Dr. Ajith Kumar, one of my professors at the Wildlife Institute of India, while teaching us the methods of documenting and measuring primate behavior in the wild, made the observation that the daily time-budget and diet of monkeys—Bonnet Macaques—in Chennai (and other South Indian cities) consist of hanging around people’s kitchens and eating idli (steamed rice-and-lentil cakes) for breakfast. Just like the human inhabitants of those cities. Nearby, House Crows watch people keenly and dart into kitchens through open windows in sudden snack attacks that startle the human inhabitants but seldom draw more than a frustrated yell or an expertly dodged broom thrown in retaliation. Like their Scrub Jay cousins in California, and other corvids around the world, these Chennai residents have figured out when and where to obtain food reliably in the urban maze. House Sparrows in many a quaint European city start their mornings—and likely spend the rest of the day too—hanging around the outdoor tables of streetside cafes, waiting for crumbs of croissant or baguette (maybe bagel for their cousins who’ve settled across the Atlantic) dropped accidentally or on purpose by the patrons. Meanwhile in Tempe. Arizona, in the xeriscaped backyard of Dr. Dave Pearson, an entomologist at Arizona State University, large flocks of birds show up every dawn like clockwork. These mixed flocks include non-native city slickers like the House Sparrow and Inca Dove alongside Sonoran Desert natives like Abert’s Towhee, House Finch, White-Winged Dove, Cactus Wren, and Curve-billed Thrasher. And they all wait patiently (but not for long) every morning for Dave to bring out bags of birdseed to replenish the feeding stations at designated spots throughout his yard.

House Sparrows in many a quaint European city start their mornings—and likely spend the rest of the day too—hanging around the outdoor tables of streetside cafes, waiting for crumbs of croissant or baguette (maybe bagel for their cousins who’ve settled across the Atlantic) dropped accidentally or on purpose by the patrons. Meanwhile in Tempe. Arizona, in the xeriscaped backyard of Dr. Dave Pearson, an entomologist at Arizona State University, large flocks of birds show up every dawn like clockwork. These mixed flocks include non-native city slickers like the House Sparrow and Inca Dove alongside Sonoran Desert natives like Abert’s Towhee, House Finch, White-Winged Dove, Cactus Wren, and Curve-billed Thrasher. And they all wait patiently (but not for long) every morning for Dave to bring out bags of birdseed to replenish the feeding stations at designated spots throughout his yard. Examine the city from an ecological perspective, as an ecosystem built for humans, and a few features about the rhythm of city life stand out. We built cities to escape the vagaries of nature, its seasonal cycles and annual and decadal fluctuations which make life challenging. In the city, we shelter from extremes of climatic cycles, insulating ourselves in increasingly climate-controlled indoor environments. Outdoors, cities even create their own local climate bubbles, heat islands which mitigate the northern winters and herald a globally warmed up future. We have now altered the flow of food and water across the planet, funneling much of the products of plant/animal/human labor into cities that blanket the lands as busy hubs in an ever tightening web of highways and railways. Our network of cities in this globalized world is thus the culmination of our millenia-long quest to free ourselves from the contraints of nature’s cycles. So we can now eat mangos and cherries in the middle of a northern winter, and never seem to be too far away from an all-you-can-eat buffet of foods fast and slow. In harvesting so much of the Earth’s primary productivity for ourselves, we have succeeded in raising and flattening out the fluctuations in natural cycles of nutrient flows. Where our ancestors (and some increasingly small indigenous communities even now) flowed across the landscape keeping a close eye on the flushing of leaves, blooming of flowers, ripening of fruits, and the local or long-distance migrations of fish and bird and mammal, worrying about where the next meal was coming from, we now mostly worry about when the bakery around the corner opens in the morning so we can get in line before the fresh bagels are sold out. The ebbs and flows in our food supplies have been replaced by a more steady stream, and the rhythm of food availability now pulses to a new urban beat, set more by the convenience of our social arrangements rather than the rotations of the planet or its cycling around the sun.

Examine the city from an ecological perspective, as an ecosystem built for humans, and a few features about the rhythm of city life stand out. We built cities to escape the vagaries of nature, its seasonal cycles and annual and decadal fluctuations which make life challenging. In the city, we shelter from extremes of climatic cycles, insulating ourselves in increasingly climate-controlled indoor environments. Outdoors, cities even create their own local climate bubbles, heat islands which mitigate the northern winters and herald a globally warmed up future. We have now altered the flow of food and water across the planet, funneling much of the products of plant/animal/human labor into cities that blanket the lands as busy hubs in an ever tightening web of highways and railways. Our network of cities in this globalized world is thus the culmination of our millenia-long quest to free ourselves from the contraints of nature’s cycles. So we can now eat mangos and cherries in the middle of a northern winter, and never seem to be too far away from an all-you-can-eat buffet of foods fast and slow. In harvesting so much of the Earth’s primary productivity for ourselves, we have succeeded in raising and flattening out the fluctuations in natural cycles of nutrient flows. Where our ancestors (and some increasingly small indigenous communities even now) flowed across the landscape keeping a close eye on the flushing of leaves, blooming of flowers, ripening of fruits, and the local or long-distance migrations of fish and bird and mammal, worrying about where the next meal was coming from, we now mostly worry about when the bakery around the corner opens in the morning so we can get in line before the fresh bagels are sold out. The ebbs and flows in our food supplies have been replaced by a more steady stream, and the rhythm of food availability now pulses to a new urban beat, set more by the convenience of our social arrangements rather than the rotations of the planet or its cycling around the sun.

In addition to the interest and enthusiasm of my students, and a personal desire to re-initiate some activism in myself, the exercise takes its inspiration from, and was informed by, two emerging threads in recent landscape, urban ecology and restoration ecology literatures. The first relates to the application of landscape ecology principles in a constructive, futuristic, manner to the urban context and the second to the notion of using ‘charismatic’ species to engage society, emerging in the restoration ecology literature. A third, more personal consideration, relates to the notion of activism, and in how we position ourselves as participants in a relatively young democracy in South Africa (and one that was significantly informed by activism) in response to current causes.

In addition to the interest and enthusiasm of my students, and a personal desire to re-initiate some activism in myself, the exercise takes its inspiration from, and was informed by, two emerging threads in recent landscape, urban ecology and restoration ecology literatures. The first relates to the application of landscape ecology principles in a constructive, futuristic, manner to the urban context and the second to the notion of using ‘charismatic’ species to engage society, emerging in the restoration ecology literature. A third, more personal consideration, relates to the notion of activism, and in how we position ourselves as participants in a relatively young democracy in South Africa (and one that was significantly informed by activism) in response to current causes.

Our seed bomb making event was fortuitously followed by a day of rain and on Sunday morning we targeted vacant lots and road verges. We made sure our sites had limited alien grass cover to reduce overwhelming competitive dynamics and were well positioned for maximum public benefit. Then we bombed these sites hard. We tossed over-arm, we threw under-arm, we chucked them hard at the ground to watch them break apart, we competed to see who could throw the highest, and we jumped on some, and placed some gently in divots in the ground. We had so much fun! The act of hurling a seed bomb was warming to the heart. To throw something is such a physical act and really did galvanize the activist in me giving me all the gorgeous feelings of righteous action.

Our seed bomb making event was fortuitously followed by a day of rain and on Sunday morning we targeted vacant lots and road verges. We made sure our sites had limited alien grass cover to reduce overwhelming competitive dynamics and were well positioned for maximum public benefit. Then we bombed these sites hard. We tossed over-arm, we threw under-arm, we chucked them hard at the ground to watch them break apart, we competed to see who could throw the highest, and we jumped on some, and placed some gently in divots in the ground. We had so much fun! The act of hurling a seed bomb was warming to the heart. To throw something is such a physical act and really did galvanize the activist in me giving me all the gorgeous feelings of righteous action.

The

The  Old habits are hard to change. The Palo Verde makes it difficult to access one of the converted garages if the designated owner of the garage wished to park in it regularly. That building owner — whose garage is now more difficult to access — now would like to park a car in the garage for the six months of the year during which they are absent. Because the tree blocks easy access it has been cast as potentially causing “adverse possession” by that owner. Fellow building owners have offered to switch garages or to pay for off site garaging. The car can be parked, but it requires skill and maneuvering to do so. Moreover, the driveway is now lined by small boulders and is a gardening space, the back area is covered with pavers that are not well embedded in the soil, so moving a car across these areas is not easy and would damage the people centric and oriented new infrastructure. The owner who would like to park the car has suggested either moving the Palo Verde (now 30 feet tall), or planting another at the edge of the property and when it has grown, cutting this one down. Or failing compromise (that is, the acceptance of one of these options), cutting the tree down by fiat.

Old habits are hard to change. The Palo Verde makes it difficult to access one of the converted garages if the designated owner of the garage wished to park in it regularly. That building owner — whose garage is now more difficult to access — now would like to park a car in the garage for the six months of the year during which they are absent. Because the tree blocks easy access it has been cast as potentially causing “adverse possession” by that owner. Fellow building owners have offered to switch garages or to pay for off site garaging. The car can be parked, but it requires skill and maneuvering to do so. Moreover, the driveway is now lined by small boulders and is a gardening space, the back area is covered with pavers that are not well embedded in the soil, so moving a car across these areas is not easy and would damage the people centric and oriented new infrastructure. The owner who would like to park the car has suggested either moving the Palo Verde (now 30 feet tall), or planting another at the edge of the property and when it has grown, cutting this one down. Or failing compromise (that is, the acceptance of one of these options), cutting the tree down by fiat. Similar reactivity to nature replacing car space is found in the note from the neighbor about our plants in the front planting strip. The 8 foot tall

Similar reactivity to nature replacing car space is found in the note from the neighbor about our plants in the front planting strip. The 8 foot tall  These incidents make me aware of profound difficulties in changing neighborhoods to less car dependency and the car rights mentalities, as well as instituting plant pallates that are out of the ordinary. Our neighbor was clearly advocating we recreate the planting strip lawn to be more in harmony with the rest of the street. Our building neighbor is more divided about things. Acknowledging the beauty of the tree and the pleasantness of the back area, the owner is attempting to finesse a situation that probably cannot be. We can have the tree and plants, or remake a car infrastructure, but not both. This is hard to admit.

These incidents make me aware of profound difficulties in changing neighborhoods to less car dependency and the car rights mentalities, as well as instituting plant pallates that are out of the ordinary. Our neighbor was clearly advocating we recreate the planting strip lawn to be more in harmony with the rest of the street. Our building neighbor is more divided about things. Acknowledging the beauty of the tree and the pleasantness of the back area, the owner is attempting to finesse a situation that probably cannot be. We can have the tree and plants, or remake a car infrastructure, but not both. This is hard to admit. While my examples may seem petty, they are emblematic of the attitudinal issues, reinforced by 20th century codes and conventions and infrastructure, that make current cities hard to change. We have coevolved hard and soft infrastructures that reinforce one another to harden pathways that then reinforce each other. Soft infrastructures include the rules — street widths, sidewalk widths, planting regulations, parking provisions and regulations. Hard infrastructures are the product of those soft infrastructures, but then reinforce them because they become normalized and an architecture of dependence gets erected upon them. These include the conflation of car access with property values. The challenges of the 21st century will include unraveling the knot of this reinforcing interaction between hard and soft infrastructures in our urban areas. To make friendly spaces for nature, the most obvious open space is that devoted to cars. Car infrastructure — parking lots, parking garages, parking garages, parking spaces, streets — create multiple negative externalities. These include polluted run off, lack of permeable filtration areas, heat islands, unwalkable urban spaces, not to mention facilitating cars that produce air pollution and GHGs; the list is long. To reduce energy use in urban areas, we must also begin to use readily available nature’s services like direct sunlight to dry clothes!

While my examples may seem petty, they are emblematic of the attitudinal issues, reinforced by 20th century codes and conventions and infrastructure, that make current cities hard to change. We have coevolved hard and soft infrastructures that reinforce one another to harden pathways that then reinforce each other. Soft infrastructures include the rules — street widths, sidewalk widths, planting regulations, parking provisions and regulations. Hard infrastructures are the product of those soft infrastructures, but then reinforce them because they become normalized and an architecture of dependence gets erected upon them. These include the conflation of car access with property values. The challenges of the 21st century will include unraveling the knot of this reinforcing interaction between hard and soft infrastructures in our urban areas. To make friendly spaces for nature, the most obvious open space is that devoted to cars. Car infrastructure — parking lots, parking garages, parking garages, parking spaces, streets — create multiple negative externalities. These include polluted run off, lack of permeable filtration areas, heat islands, unwalkable urban spaces, not to mention facilitating cars that produce air pollution and GHGs; the list is long. To reduce energy use in urban areas, we must also begin to use readily available nature’s services like direct sunlight to dry clothes!

1 Comment

Join our conversation