0

There’s an old saying about defecating and eating and not doing both in the same place. It is usually applied to interpersonal relations but serves just as well for industrial ones. And it is particularly relevant to mining. Certainly we don’t want to mine directly upstream of water intake sites, blast into rock near dense human settlements or leave scarred sites unrehabilitated. But as the scramble for increasingly scarce resources intensifies and the price of energy escalates, our axiom becomes increasingly untenable. Material flows are intensifying as their travel distances are shortening. With resource extraction, separation and containment are becoming less and less viable.

Offsetting the damage that mining does in one area by compensating with another less-disturbed site — which suggests that a landscape is composed of interchangeable pixels — is making it even harder. As the world effectively shrinks we may well have to eat, draw water and live where our waste ends up. Indeed in many ways we urbanites already are. Why shouldn’t this be a good thing? Cities have long been accruing refined products and are poised to deliver higher recycling yields than they currently are. We need to rewrite the equation so that cities — rather than being the distant instigators and, increasingly, victims of mining — are at the center of the metabolic loop.

1 Minerals

In the last local election in New York State, in November 2013, the question of whether to allow mining in an upstate forest preserve was put to the voters, including those in downstate — and potentially downstream — New York City. This made me happy. Even if some 400 km away, having a say in what happened in the far north was poetic justice since the distant State government had long held sway over local issues within New York City borders. (In fact some contend that the State government has long been ‘mining’ the City by spending less than 10% of the City’s tax revenue on City-related concerns.) It was also the first time I remember being able to directly vote on an environmental issue.

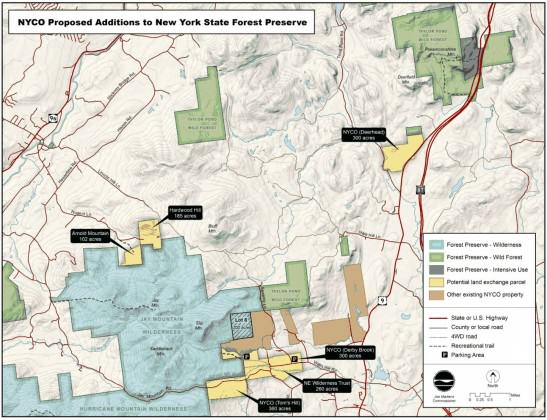

One of six on the ballot, Proposal Five was to amend a portion of the State Constitution to allow mineral extraction on roughly 1 km2 of land within Adirondack Park. Adopted in 1894, that portion of the State Constitution protected the 25,000 km2 Adirondack Park as off limits for sale or lease. Second to the higher-profile Mayoral election, all six Proposals were hidden on the back of the ballot like the throwaway songs on the ‘B side’ of a vinyl record. (20 per cent of voters didn’t even bother to flip it over. In New York City, 40 per cent of voters ended up abstaining on the referenda.) Still, I was sure New York’s voters would reject it.

Though it was the only Proposition on which New York City disagreed with the rest of the state, the measure narrowly passed with 53% of votes in favor of constitutional amendment. I was tempted — as I often am — to cast bad design as the villain. (The election in the State of Florida in 2000 illustrates the spectacular fiasco that poorly designed ballots can create.) But the culprit in this election was probably far more banal: simple ignorance. As a result NYCO Minerals, a private corporation, will extract wollastonite — a fairly anodyne mineral conventionally used in ceramics, plastics and asbestos replacement — from within a protected area.

Some ‘yes’ voters’ consciences may have been assuaged by the Proposal’s offset arrangement whereby an equivalent amount of land outside the current preserve would be substituted for the piece surrendered within. But New York State may be setting a more ominous precedent. This will be the first ever land swap within Adirondack Park — the largest park in the contiguous US, roughly the size of Albania or Rwanda — for private commercial profit. If NYCO Minerals were to go out of business the extracted land might not be returned to the public trust. In an age of global resource grabs and trade-offs with sometimes catastrophic consequences, the Adirondack mining expansion is relatively small scale. Still, it provides a fascinating lens through which to view the rural-urban continuum and it touches on the wider issues of tradeoffs between economy and environment, geopolitics and offsets.

Edward McClelland writes that ‘[a]n industrial city follows the same life cycle as a prizefighter or a prostitute. Its native beauty, the freshness of its earth and water, the youth and strength of its people, are used up and discarded’. Whereas downstate New York City remains a global financial capital, upstate New York State — like most of the Rust Belt that extends west across the Great Lakes — has never fully recovered from the loss of its manufacturing base. It is easy to understand why the region would seek to attract new jobs. On the other hand, if one doesn’t have a personal (and direct) stake in the economic gains, it is also easy to criticize prioritizing short-term economic gains for more dubious long-term environmental health. As it turns out, the new NYCO mine is expected to support just 100 jobs. In Essex County, where the mining site is located, 65% of voters supported Proposal Five (37% of some 26,000 eligible voters voted in Essex County), where conservatives outnumber liberals 2 to 1. That support — and general turnout — declined with distance to a low of 29% in remote New York City (24% of some 4.6 million eligible voters voted in New York City, where liberals outnumber conservatives 6 to 1).

While not one of the sexier rare earth minerals famed for their cool performance under high-heat conditions, wollastonite is nonreactive and bright. Second only to China in global production, the US extracts all of its wollastonite from two existing mines in the New York Adirondacks. The mines never sleep, operating 24/7 until the day they are tapped out and closed. One is reaching the end of its life and the land swap now allows NYCO to replace it with another. Increasingly wollastonite is being used as a performance-enhancing additive in concrete, which is now the second-most used resource in the world behind water itself. For the world’s most rapidly urbanizing areas access to concrete is essential. The wollastonite from the new mine may well end up deposited in the new skyscrapers of expanding cities around the world. Perhaps even in New York City itself, which anticipates a net gain of more than half a million residents by 2030.

In 2012 NYCO’s parent company was acquired by a minerals conglomerate in Athens that controls more than 100 mines in 20 countries, representing a diversification of supply and dispersal of risk. Environmental offsets such as the one represented by this land swap suggest that we can neutralize the sins we make in one area by compensating for them in another. Applied spatially, offsets treat land as an undifferentiated field of pixels, any of which could be swapped for another. But of course the effects of land and habitat degradation cannot be easily contained. And the false equivalency of ‘here for there’ distracts from the wider issues of land fragmentation and watershed degradation. Yet, in the ‘iTunes’ mentality of the early 21st century, New York State’s voters seemed content to see this story as two micro-targeted areas of interest in ignorance of the interrelated whole surrounding them.

2 Water

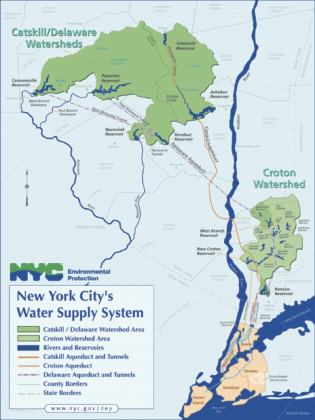

As it turns out, New York City is not actually part of the same watershed as the NYCO mines. Though the Hudson River also originates in the Adirondacks, the new Adirondack mining site is drained by a watershed that ultimately flows northward to the St Lawrence River, just downstream of Montreal. New York City’s vaunted tap water comes from another watershed, the Delaware-Catskill, which ultimately empties out further south near Philadelphia. Still, the themes of economy vs. environment and pixilated offsets have been playing themselves out over the wider politics of the US.

It has been said that upstate New York was the victim of its own ingenuity. In response to demands of the New York City printing industry, a Buffalo engineer more or less invented air conditioning in 1902. Air conditioning spread rapidly across the hotter, drier southern US, making the naturally mild climate and plentiful water supply of the northern Great Lakes region less of an advantage. Over the next decades, then, a great many factories left the north for the weaker labor and environmental regulations of the south. The fastest growth in the US still persists in the Sun Belt states. However, long forgotten upstate New York and the rest of the Rust Belt may have the last laugh if recent, record draughts in the Sun Belt prove more than a passing exception. California is now experiencing the worst drought in 500 years. Traditional extraction-friendly states like Texas and Oklahoma are seeing no better. The Executive Director of the Associate of California Water Agencies said that ‘[his] industry’s job is to try to make sure that these kind of things never happen. And they are happening.’

In West Virginia mining-related water troubles have been plaguing some 300,000 residents around the city of Charleston since early January when 20,000 litres of 4-methylcyclohexane methanol (MCHM) seeped out of storage tanks of Freedom Industries into the Elk River, just upstream of the water intake for the region. Exposure to MCHM in the local tap water has caused headaches, nausea skin irritation and difficulty breathing. Though the chemical has long been used in the processing of coal mined from the surrounding mountains, its human and environmental effects have never been thoroughly tested. In response to criticisms that the State was not doing enough to provide water and mitigate public health risk, the Governor simply said ‘[i]t’s your decision […] if you do not feel comfortable, don’t use it.’

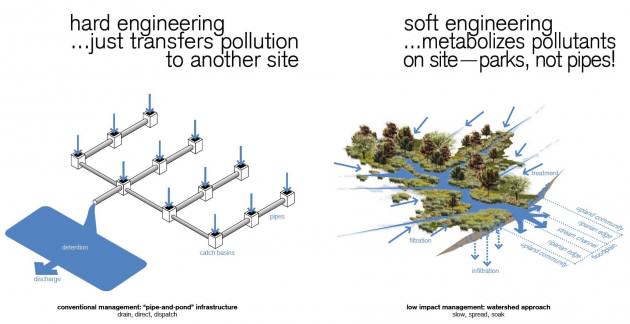

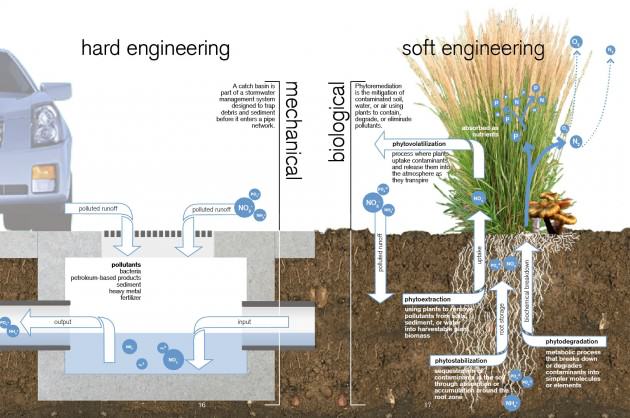

Faced with multiple lawsuits over the Elk River spill, Freedom Industries filed for bankruptcy. There were other, less successful attempts to pick up and move on. While the tap water prohibition was still in effect the local water company allegedly attempted to provide untainted water in trucks on a point-by-point basis. The problem was the source of that water: the same Elk River, two km downstream from the chemical spill site. Either they did not understand or hoped no one else would notice that, where water is concerned, a polluted site cannot so easily be substituted for a non-polluted one. An increasingly dispersed scramble for diminishing supply is driving some increasingly desperate attempts to access resources where deposits are costly to access and rife with side effects. Extraction at this scale and intensity is seriously calling into question whether containment and offsets can actually work.

3 Oil and gas

Mining and water supply in New York State remain fairly well regulated, but what does potentially threaten New Yorkers’ water supply is the specter of hydraulic fracturing, commonly known as ‘fracking’. Use of the procedure is accelerating as much of the world’s low-hanging fruit, in terms of energy, disappears. Injecting high-pressure chemicals, water and sand into deep rock strata can liberate otherwise difficult-to-access places. But it is also premised on the gauzy hope that the desired substances — and only the desired ones — will be released. In fact, side effects not infrequently include ground water contamination of ground water, fresh water depletion — especially in the drought-afflicted areas of the Great Plains — air pollution and the migration of gases and hydraulic fracturing chemicals to the surface.

Proponents contend that it is safe when properly executed. Yet there remains so much that is uncontrollable and, frankly, unknown. And when potential profits exceed the litigation costs of possible environmental disaster, we are digging ourselves into a hole that is both spatially and metaphorically deeper than we have bargained for. Fracking represents a kind of three-dimensional pixellization in which chemicals are injected underground, often across vast areas and beneath settlements under the shaky assumption that its effects — whether contamination, tectonic shift or others — will not percolate beyond the target area. Nevertheless, widespread complaints in four US states (Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas and West Virginia) suggest its effects are far from contained. In one viral example, a North Dakota man who lives in a fracking zone has posted an online video of him lighting his tap water on fire.

Until now, fracking has been banned in New York State. However, the ban is currently under review and many civil society organizations worry that intense industry lobbying may pressure Governor Cuomo. A new energy plan recently issued by the State does not include fracking as part of its long-term strategy, though it remains agnostic on the issue as a whole. But the Governor’s wider decision has yet to be announced, perhaps before November 2014. There is concern about the potential effect on the Delaware-Catskill watershed: if the state’s fracking ban were lifted, would New York City forfeit its waiver of the national water filtration requirement?

Until now, fracking has been banned in New York State. However, the ban is currently under review and many civil society organizations worry that intense industry lobbying may pressure Governor Cuomo. A new energy plan recently issued by the State does not include fracking as part of its long-term strategy, though it remains agnostic on the issue as a whole. But the Governor’s wider decision has yet to be announced, perhaps before November 2014. There is concern about the potential effect on the Delaware-Catskill watershed: if the state’s fracking ban were lifted, would New York City forfeit its waiver of the national water filtration requirement?

Two weeks ago we saw the environmental impact assessment for the Keystone XL pipeline that would increase the capacity to transport oil from Canadian fields to the US Gulf Coast for shipping. Like the NYCO minerals mine, the lifespan of the existing pipeline is near its end and expanded fracking is raising transport demand. But while a revised route has Keystone XL circumventing the fragile Nebraska Sand Hills, 400 km of it would still cross the highly superficial 450,000 km2 Ogallala Aquifer that supplies water to more than 2 million people. The report takes the shockingly cynical position that since climate-damaging fracking would essentially be taking place anyhow, the pipeline might as well be built. As we double down on our unsustainability, Godfrey Reggio’s film Koyaanisqatsi comes immediately to mind. But what is troubling about this movie is that it is so beautiful we almost forget to be alarmed by its wider message. Clearly it is ‘Life Out of Balance’, but the spectacle and sheer kinetic energy of so much production and consumption is dazzling. I wonder whether we are complacent or just bedazzled by it all. Or both?

1* Garbage

Interestingly, local environmental advocacy groups were somewhat divided on the merits (or evils) of the NYCO land swap. National environmental groups such as the Sierra Club joined Protect the Adirondacks in opposing it because of the precedent established by swapping land for private profit. On the other hand, Adirondack Council and Adirondack Mountain Club believe the 100 jobs and 7 km2 of forest land in exchange make it worthwhile. NYCO Minerals, which will operate the new wollastonite mine in the Adirondacks, has a record of restoring former mining scars to a modicum to habitat recovery. But, as past attempts have shown, a multi-storey hole in the ground is a drastic change and recovering mixed-growth, biodiverse habitat takes many human generations; far beyond the extremely narrow window of opportunity we have to tackle climate change and biodiversity loss. But we are running out of time and land, and the metabolic circle is tightening.

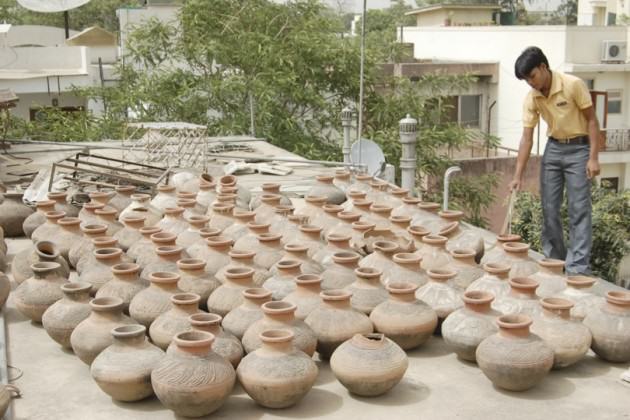

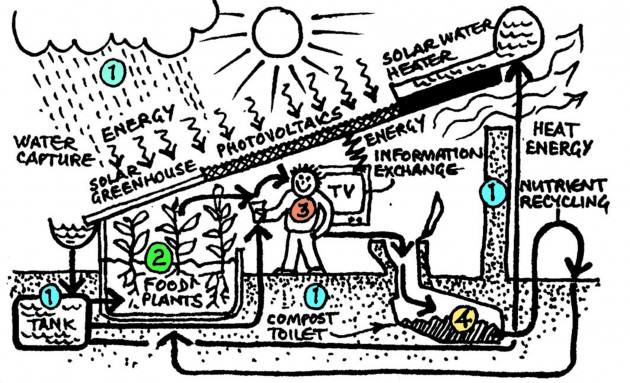

Consumption in population-heavy areas often instigates the rural mining that comes back to haunt those same areas in the form of contaminated water and food supply. Urban areas are usually seen as both the perpetrators and victims of unsustainable extraction. But they could be heroes, if their consumption literally fueled itself. Turning waste into inputs allows us close the loop on material flows. Whereas mineral ores have accrued over many millennia, cities often accrue valuable deposits over mere decades. The substances extracted and refined elsewhere are ‘redeposited’ into the buildings, landfills, sewers and other infrastructural systems of the city. In The Economy of Cities Jane Jacobs wrote about the city as a ‘waste-yielding mine’. By transforming that which is challenging and dangerous (and in any case difficult to contain), such as sulfur dioxide and fly ash, into a valuable asset.

Much earlier, and clearly inverting our earlier axiom, Paris achieved an elegantly circular metabolism of its food system whereby ‘night soil’ (i.e. human solid waste) was collected and redistributed as fertilizer to peri-urban farms. Since then, urban mining has reemerged in ways both intentional and informal. In many Rust Belt cities of the North American Great Lakes region, abandoned building stock that remains is frequently vulnerable to theft. Rather than going for typical consumer end products, renegade urban ‘miners’ strip the copper pipes and wiring from the buildings’ plumbing and electrical systems. Clearly this does not qualify as a ‘best practice’, but it signifies the increasing value seen in urban material deposits.

McClelland writes ‘[a]fter a car maker or a steel mill wears out a factory, extracts all the tax breaks a treasury will bear, and accumulates more obligations to its workers than the stockholders will bear, it flees town like a deadbeat husband, leaving a worn-out, exploited patch of land no one else will touch.’ Nevertheless, China has begun to invest in whole portions of cities in the US Rust Belt. For example, Toledo’s recently-obsolete, bargain-priced built infrastructure — and its easy fresh water supply — is a valuable asset to high-growth, limited-resource China. One high-growth economy is taking advantage, like a hermit crab, of the unoccupied urban shell of another. On some level this may be speculation on temporarily undervalued urban space. But it also effectively represents an innovative form of mining of post-industrial urban detritus.

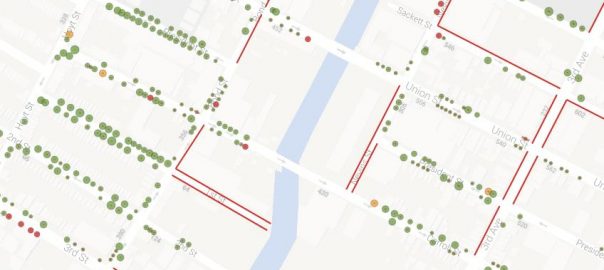

Other more formal ways have been widely touted for their ability to transform problems into solutions. A number of cities including New York have begun generating power from methane emitted by landfills. A few such as Singapore have taken to purifying and transforming waste water into drinking water. Other cities are looking to generate power from the waste water that they collect and consolidate, 30% of the energy embedded in which can be readily reused. Most common, in any case, is the recycling of e-waste for more common and rare earth metals. The informal settlement of Dharavi, in Mumbai, continues to exemplify that cities are mines as profitable as conventional ones in rural areas, and they favor a more granular approach suited to SMEs. The continued obstacles of toxicity and child labor are formidable, but with better environmental and worker safety standards they can also provide work that is more decent.

The elephant in the room, or course, is energy consumption. Continued development is predicated — as it always has been — on a continuous supply cheap energy. But existing sources of minerals, water, oil and gas can only be extracted at an increasingly untenable financial and environmental cost. Cities can at least help with relative decoupling of growth from energy consumption and reduce energy demands in transport and building sectors (which are already responsible for approximately two-thirds of energy consumption globally). Shared infrastructure that reduces per capita demand. Material flows analyses are being undertaken by MIT and others. These analyses aim to account for all inputs, transformations and sinks generated through the city-regions’ production, distribution and consumption systems.

In the city, however, we are not necessarily faced with the binary of environment or jobs. Here we can have both if unwanted outputs become desirable inputs by exploiting cities’ highly concentrating infrastructural systems. ‘[City] mines will differ from any now to be found because they will become richer the more and the longer they are exploited. The law of diminishing returns applies to other mining operations: the richest veins, having been worked out, are gone forever. But in cities, the same materials will be retrieved over and over again. New veins, formerly overlooked, will be continually opened. And just as our present wastes contain ingredients formerly lacking, so will the economies of the future yield up ingredients we do not now have’ (Jacobs). Eldorado may not be a distant, legendary city of dazzling gold, but rather– as Calvino painted — our very own city built of cast-off things, whose riches are hidden underfoot. We may as well be bedazzled by it all. But there’s no need for cynicism.

Andrew Rudd

New York

Some weak points that need to be developed

Some weak points that need to be developed

Jerusalem is characterized topographically by the watershed that draws a clear divide between the eastern side, a desertscape of great beauty with many historic features, including the magnificent Kidron/Wadi El Nar Basin, running down to the Dead Sea, and the western side, with the green rolling Jerusalem Hills, abundant water sources and fertile valleys. The physical contrast between these two microclimates is dramatic, and very much an integral part of Jerusalem’s magic and majesty.

Jerusalem is characterized topographically by the watershed that draws a clear divide between the eastern side, a desertscape of great beauty with many historic features, including the magnificent Kidron/Wadi El Nar Basin, running down to the Dead Sea, and the western side, with the green rolling Jerusalem Hills, abundant water sources and fertile valleys. The physical contrast between these two microclimates is dramatic, and very much an integral part of Jerusalem’s magic and majesty.

In the 1990’s an attempt was made to convert the sixty acres of the park into a residential neighborhood with a business center, then considered worthy urban objectives. The land had previously been allocated to two collective farms that had been asked to grow fruit for Jerusalem under siege during Israel’s War of Independence. The orchards were planted already in the 1940’s and provided a source of fresh fruit for residents during the six-month siege in 1948. During those difficult months, Jerusalemites had a meager water supply thanks to the rainwater cisterns that have been part of life in Jerusalem for thousands of years.

In the 1990’s an attempt was made to convert the sixty acres of the park into a residential neighborhood with a business center, then considered worthy urban objectives. The land had previously been allocated to two collective farms that had been asked to grow fruit for Jerusalem under siege during Israel’s War of Independence. The orchards were planted already in the 1940’s and provided a source of fresh fruit for residents during the six-month siege in 1948. During those difficult months, Jerusalemites had a meager water supply thanks to the rainwater cisterns that have been part of life in Jerusalem for thousands of years.

The Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel fought the battle for the Gazelle Valley in the planning committees and the courts, eventually winning the case by proving that percentage-wise, this space needed to be left open to enable intensive development in the surrounding neighborhoods. Without realizing, we were making the case for preservation of urban nature, and indeed for the multiple eco-system services it provides. Those that argued in favor of intensive residential development in the valley claimed that the pro urban nature camp was hypocritical, since by not developing the Gazelle Valley we would push urbanization further into suburbs on the west side of Jerusalem, where the really important natural resources are. So we were accused of conducting a NIMBY fight to prevent building in our back yards.

The Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel fought the battle for the Gazelle Valley in the planning committees and the courts, eventually winning the case by proving that percentage-wise, this space needed to be left open to enable intensive development in the surrounding neighborhoods. Without realizing, we were making the case for preservation of urban nature, and indeed for the multiple eco-system services it provides. Those that argued in favor of intensive residential development in the valley claimed that the pro urban nature camp was hypocritical, since by not developing the Gazelle Valley we would push urbanization further into suburbs on the west side of Jerusalem, where the really important natural resources are. So we were accused of conducting a NIMBY fight to prevent building in our back yards.

When it came to planning the park in preparation for the actual development, an additional element of great significance for Jerusalem was brought into the picture.

When it came to planning the park in preparation for the actual development, an additional element of great significance for Jerusalem was brought into the picture. As I submit this entry to the TNOC blog, the fence around the valley, which will provide protection for the gazelles from the heavy traffic all round, and from marauding wild dogs, is nearing completion, and so is the rainwater collection system I have described. The many ancient agricultural terraces around the valley will be restored, and a bike path will run round the entire park, as well as along the axis of lakes and streams. A Visitors’ Center will provide educational material and information for tourists. There will be no lighting in the park after 22:00, and the park will be closed to the public at night, with no entry fee during opening hours.

As I submit this entry to the TNOC blog, the fence around the valley, which will provide protection for the gazelles from the heavy traffic all round, and from marauding wild dogs, is nearing completion, and so is the rainwater collection system I have described. The many ancient agricultural terraces around the valley will be restored, and a bike path will run round the entire park, as well as along the axis of lakes and streams. A Visitors’ Center will provide educational material and information for tourists. There will be no lighting in the park after 22:00, and the park will be closed to the public at night, with no entry fee during opening hours.

What Does Urban Nature-Related Graffiti Tell Us? A Photo Essay from the City of Cape Town

What Does Urban Nature-Related Graffiti Tell Us? A Photo Essay from the City of Cape Town Wicked Problems, Social-ecological Systems, and the Utility of Systems Thinking

Wicked Problems, Social-ecological Systems, and the Utility of Systems Thinking A Worldview of Urban Nature that includes “Runaway” Cities

A Worldview of Urban Nature that includes “Runaway” Cities Open Mumbai: Re-envisioning the City and Its Open Spaces

Open Mumbai: Re-envisioning the City and Its Open Spaces A Comic Book Sparks Kids Toward Environmental Justice

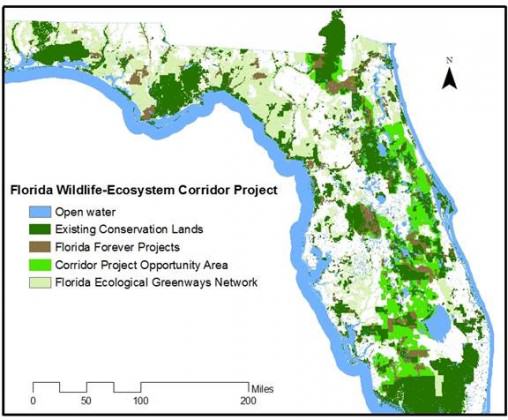

A Comic Book Sparks Kids Toward Environmental Justice Cities as Refugia for Threatened Species

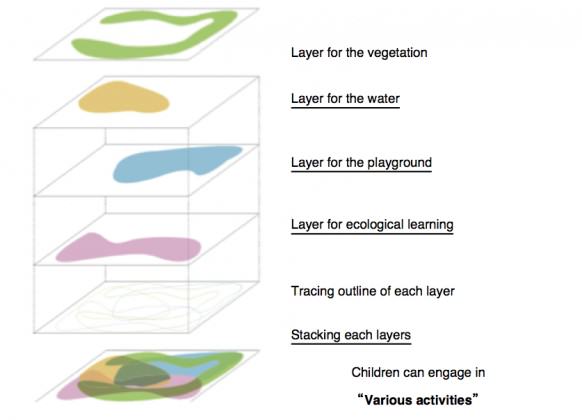

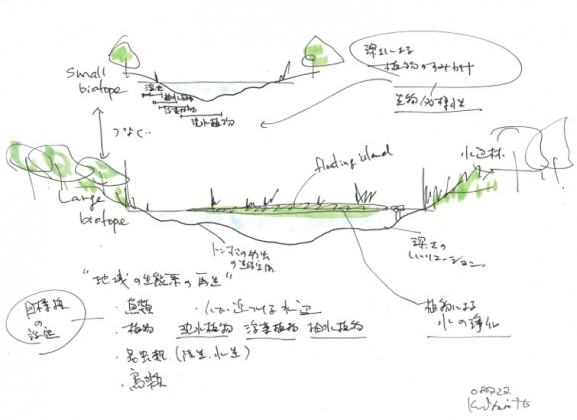

Cities as Refugia for Threatened Species “Growing Place” in Japan—Creating Ecological Spaces at Schools that Educate and Engage Everyone

“Growing Place” in Japan—Creating Ecological Spaces at Schools that Educate and Engage Everyone Architecture and Urban Ecosystems: From Segregation to Integration

Architecture and Urban Ecosystems: From Segregation to Integration Urbanophilia and the End of Misanthropy: Cities Are Nature

Urbanophilia and the End of Misanthropy: Cities Are Nature Re-imagining Nairobi National Park: Counter-Intuitive Tradeoffs to Strengthen this Urban Protected Area

Re-imagining Nairobi National Park: Counter-Intuitive Tradeoffs to Strengthen this Urban Protected Area Up the Creek, With a Paddle: Urban Stream Restoration and Daylighting

Up the Creek, With a Paddle: Urban Stream Restoration and Daylighting It Is Time to Really “Green” the Marvelous City

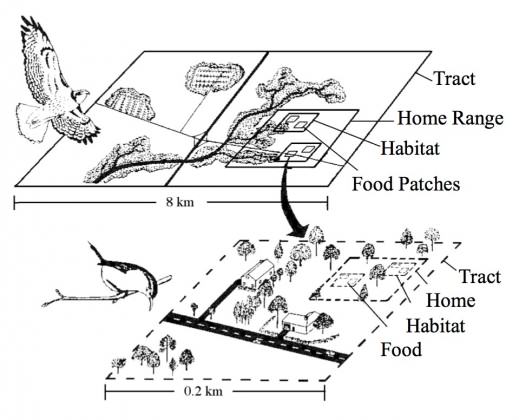

It Is Time to Really “Green” the Marvelous City Lessons from a One-eyed Eagle

Lessons from a One-eyed Eagle

Thus, the importance of cities living in harmony with nature has been emphasised. The ancient Indian science

Thus, the importance of cities living in harmony with nature has been emphasised. The ancient Indian science

Somehow it seems fitting that a one-eyed eagle calls this place home. By all rights, the island should have been paved over long ago. Despite the odds, it somehow survived, decade after decade as the landscape around it developed. The odds are against it now too. The big money and conventional wisdom say development is inevitable — we need to prepare for the future. But sometimes the conventional wisdom is wrong; sometimes we need to think beyond the experts or perhaps seek out different sources of wisdom. Sometimes the path forward is written not in technical reports, but on the side of a canoe and in the stories of our fellow travelers, the stories that usually don’t make it into technical reports.

Somehow it seems fitting that a one-eyed eagle calls this place home. By all rights, the island should have been paved over long ago. Despite the odds, it somehow survived, decade after decade as the landscape around it developed. The odds are against it now too. The big money and conventional wisdom say development is inevitable — we need to prepare for the future. But sometimes the conventional wisdom is wrong; sometimes we need to think beyond the experts or perhaps seek out different sources of wisdom. Sometimes the path forward is written not in technical reports, but on the side of a canoe and in the stories of our fellow travelers, the stories that usually don’t make it into technical reports.

The following two examples depict boats tossing in stormy seas, a strong narrative of shared, collective history in Cape Town, which was originally known as the Cape of Storms. Even today ships run aground on the shores of the City every winter and this is an aspect of nature we all share and respect.

The following two examples depict boats tossing in stormy seas, a strong narrative of shared, collective history in Cape Town, which was originally known as the Cape of Storms. Even today ships run aground on the shores of the City every winter and this is an aspect of nature we all share and respect.

Pictures of African wildlife, not present in Cape Town for hundreds of years, litter the city, calling on the larger urban populations to take up these distant conservation causes.

Pictures of African wildlife, not present in Cape Town for hundreds of years, litter the city, calling on the larger urban populations to take up these distant conservation causes.

The following graffiti is regularly updated, keeping abreast of the shocking rhino death tolls due to poaching for the illegal horn trade in conservation areas far flung from Cape Town.

The following graffiti is regularly updated, keeping abreast of the shocking rhino death tolls due to poaching for the illegal horn trade in conservation areas far flung from Cape Town.

In addition to the main city presentations on Thursday and Friday, there were a number of side events, earth walks, and workshops for participants and the general public. These includes walking tours of the Dell Stream Day-lighting project on the UVA Grounds and the Meadow Creek Stream Restoration Project (in the City of Charlottesville,

In addition to the main city presentations on Thursday and Friday, there were a number of side events, earth walks, and workshops for participants and the general public. These includes walking tours of the Dell Stream Day-lighting project on the UVA Grounds and the Meadow Creek Stream Restoration Project (in the City of Charlottesville,  One of my favorite events had to do with ants. We were joined for most of the launch by an entomology post-doc from North Carolina State University, Amy Savage. On Friday, during the bulk of our presentations from partner cities, Amy was busy setting out ant bait (including such things as Snickers bars, tuna, and pecan Sandies), attempting to see just how many species of ants she might find in and around the UVA School of Architecture. She was quite successful and discovered 13 different species in short order, in close proximity to where we were meeting. Education about this ant diversity, the habitat we were sharing that day, became something we attempted to weave into the more formal meeting and power point presentations. With Amy’s help at several points during the day we interrupted the Launch presentations with a report on what species had been found. We also produced a series of five ant collecting cards, with images of ant genus on one side and information about biophilic cities on the other side.

One of my favorite events had to do with ants. We were joined for most of the launch by an entomology post-doc from North Carolina State University, Amy Savage. On Friday, during the bulk of our presentations from partner cities, Amy was busy setting out ant bait (including such things as Snickers bars, tuna, and pecan Sandies), attempting to see just how many species of ants she might find in and around the UVA School of Architecture. She was quite successful and discovered 13 different species in short order, in close proximity to where we were meeting. Education about this ant diversity, the habitat we were sharing that day, became something we attempted to weave into the more formal meeting and power point presentations. With Amy’s help at several points during the day we interrupted the Launch presentations with a report on what species had been found. We also produced a series of five ant collecting cards, with images of ant genus on one side and information about biophilic cities on the other side. The incorporation of ants provided a visceral demonstration on the ways in which nature, much of it small and difficult to see, is all around us in cities. There is immense wonder and fascination value in ants, of course, yet urbanites are not well educated in looking for, identifying or even visualizing their existence all around us. Amy works with a wonderful initiative called the School of Ants that seeks to engage citizens in the collection and identification of ants throughout the country. They have produced a highly valuable urban

The incorporation of ants provided a visceral demonstration on the ways in which nature, much of it small and difficult to see, is all around us in cities. There is immense wonder and fascination value in ants, of course, yet urbanites are not well educated in looking for, identifying or even visualizing their existence all around us. Amy works with a wonderful initiative called the School of Ants that seeks to engage citizens in the collection and identification of ants throughout the country. They have produced a highly valuable urban  On Saturday afternoon, Amy took the ant station, including her microscope, to the Charlottesville Downtown Mall, engaging children and families walking by about the ants around them—something we called the Urban Ant Safari! In her interactions with people on the downtown mall Amy asked people to write down memories and recollections they had about ants in their past. She later compiled and shared these with us, and some were quite moving. An older woman wrote a note about her days as a child in England during WWII. She wrote, ‘When I was an evacuated little girl of 5 in WWII Britain, I used to watch ants. I dreamed of having a see through container, so that I [could] watch them work.’

On Saturday afternoon, Amy took the ant station, including her microscope, to the Charlottesville Downtown Mall, engaging children and families walking by about the ants around them—something we called the Urban Ant Safari! In her interactions with people on the downtown mall Amy asked people to write down memories and recollections they had about ants in their past. She later compiled and shared these with us, and some were quite moving. An older woman wrote a note about her days as a child in England during WWII. She wrote, ‘When I was an evacuated little girl of 5 in WWII Britain, I used to watch ants. I dreamed of having a see through container, so that I [could] watch them work.’

On Saturday morning a smaller group, mostly partner city representatives, came together to participate in a workshop to discuss and invent the new global Biophilic Cities Network. For several hours we discussed and debated key questions about what the Network could or should look like, what functions it will serve, what value it will have, and how and in what ways it might meet needs not served by other networks that exist.

On Saturday morning a smaller group, mostly partner city representatives, came together to participate in a workshop to discuss and invent the new global Biophilic Cities Network. For several hours we discussed and debated key questions about what the Network could or should look like, what functions it will serve, what value it will have, and how and in what ways it might meet needs not served by other networks that exist.

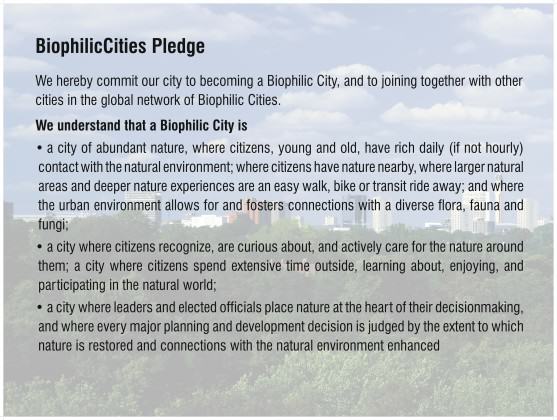

One of the most useful parts of our discussion had to do with what value of such a global network and how it would serve to strengthen the position of those in and outside city government working in support of nature. Some participants emphasized the importance of different local departments breaking out of their silos and that the network might help to do this. Others noted that the pledge card seemed to envision participants and signatories as primarily local council or local governments, but that left out universities, NGOs and many others with a stake in the network but working outside the city government.

One of the most useful parts of our discussion had to do with what value of such a global network and how it would serve to strengthen the position of those in and outside city government working in support of nature. Some participants emphasized the importance of different local departments breaking out of their silos and that the network might help to do this. Others noted that the pledge card seemed to envision participants and signatories as primarily local council or local governments, but that left out universities, NGOs and many others with a stake in the network but working outside the city government.

1 Comment

Join our conversation