Pippin Anderson

We know biodiversity in cities is a good thing. For example we have research that shows a diversity of plants provides a similar variety of livelihood options to the urban poor, some sequester carbon with a close-to-source efficiency, and others retain soil. Multiple options allow for more choice for gardens for functional and aesthetic ends. Biodiversity provides a diversity of services. We also know that people in cities govern the globe and are responsible for a sustainable future, one hinged on the preservation of global biodiversity, so it is critical that people in cities value biodiversity. Here is what we don’t know so well. We don’t know the exact workings of many of the functions or services provided by biodiversity in cities. We know some, but in truth we are just scratching the surface. We also don’t know how to really give biodiversity traction with the people who live in cities, especially in the face of significant development pressures. So, these are the two areas where I would spend my limited budget: on research towards really understanding the workings of biodiversity in cities, and then in exposing more urban citizens, in particular the young, to urban biodiversity. If the budget was really limited I would go for the second as my single action. We are sentimental creatures and hold dear what we were exposed to as children. If all we achieve on our limited budget is a growing urban population coveting biodiversity the money for the rest will follow.

Peter Werner

My message is to bring citizens more in touch with urban nature and urban biodiversity using components and methods — including values, incentives, demonstrations, etc. — that match urban lifestyle. And, urban nature provides a lot of opportunities for such components. If you present nature in cities in a way that people only links it with a rural lifestyle, with sanctity, with closed borders, and so on, then you have no chance in urban areas because urban life is the opposite of that. Here is a list of words with which the citizens of a city can be connected with urban nature and urban biodiversity: perception, awareness, appreciation, literacy, curiosity, enjoyment, excitement, surprise, astonishment, emotion, spontaneity, freedom, encouragement, integration, inclusion, involvement, participation…Wording is critical in the dissemination of messages. Notice the words I am not using in this context After the wording, activities have to follow, and here too, activities are needed which represent the sense of urban life. The new media do that best. The challenge is to include urban nature in social networks, video portals, and games (serious games) and to produce urban events and performances about urban nature, not at the edge but in the center of a city, where more people can experience them. If urbanites discover and include urban nature as part of their life, then you save public money, because biodiversity in the urban matrix will be ensured and the governance can concentrate its activities on special nature conservation projects in which rare and endangered species will be protected.

about the writer

Andre Mader

Andre is a conservation biologist specializing in subnational implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity, seconded to the Secretariat for a third year by ICLEI. FULL BIO

Andre Mader

Cities are new competitors for the finite pots of global biodiversity funding. Funding is still undoubtedly lacking elsewhere, but biodiversity in cities deserves special attention due to its extraordinary “investment” potential to influence every aspect of biodiversity conservation at every scale by affecting, en masse, people’s (voters’) attitudes. I therefore believe that the biggest bang for biodiversity buck is through the opportunity, in cities, to reach multitudes of people with a subtle but concentrated conservation message. Nothing can do this in a more reliable way than the good old zoo (and/or, in many cases, the aquarium or botanical garden). These institutions can be accessed by unprecedented numbers of people, who have flocked to them for centuries knowing that they can expect an entertainment-intensive experience. There are also “bad old zoos”, and it is critical that entertainment is subtly embellished with messages so that the experience is also an education-intensive one. Of course zoos offer the additional function of ex-situ conservation and possible reintroduction. Not insignificantly, due to their proven popularity, they are also among the few conservation options that can be net money makers and it is therefore not hard to get the private sector involved. Zoos are therefore worth the considerable cost of their establishment and even more worthwhile investing in when all that’s required is to enhance existing ones with improved interpretative facilities and improved accessibility by all sectors of the citizenry. Local governments, which commonly own or manage these institutions, would do well to consider these options, and many already do to great effect.

about the writer

Bram Gunther

Bram Gunther, former Chief of Forestry, Horticulture, and Natural Resources for NYC Parks, is Co-founder of the Natural Areas Conservancy and sits on their board. A Fellow at The Nature of Cities, and a business partner at Plan it Wild, he just finished a novel about life in the age of climate change in NYC 2050.

Bram Gunther

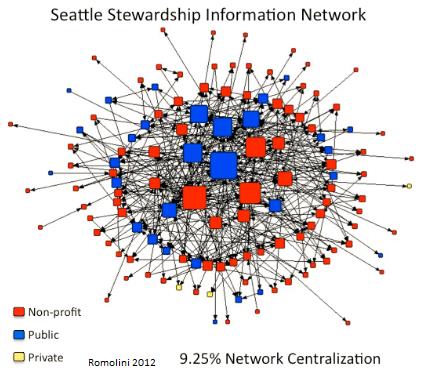

In New York City, the single most important biodiversity program recently has been the creation of the Natural Areas Conservancy (NAC), a non-profit that works in partnership with the New York City Parks Department (Parks). Parks’ Natural Resource Group is the oldest urban conservation unit in the nation, started in 1984. The management of natural areas has become critical as the City faces climate change and seeks to increase public health. The City, however, will always have limits on conservation funding. In its organization and business model, the NAC capitalizes on present-day concepts of collaborative governance and the flexibility and effectiveness of public-private partnerships to enhance and expand current conservation work. The fundamental principle of the NAC is to increase the quality of the information flow between land management and design, researchers, and decision-makers. To this effect, the NAC is funding the first ever citywide ecological and social site assessments of Parks’ natural areas, data that will be used to guide and prioritize our conservation endeavors. NAC is expanding programmatic work by funding a hydrological engineer, additional foresters, and the expansion of our Native Plant Center to grow marshland and beach plants which will be used to make our coastlines more resilient. The NAC represents a significant change in urban natural resource management, from a focus on isolated plots to a single unified ecosystem and administrative whole. The NAC is emblematic of how urban ecological management will be done in the future: public/private partnerships.

about the writer

Ana Faggi

Ana Faggi graduated in agricultural engineering, and has a Ph.D. in Forest Science, she is currently Dean of the Engineer Faculty (Flores University, Argentina). Her main research interests are in Urban Ecology and Ecological Restoration.

Ana Faggi

Recently Buenos Aires has begun a significant transformation in order to revert the lack of green spaces and the reduction of its natural capital. The City Council worked a territorial model towards 2060 for a healthy and livable urban fabric with strategies to strengthen and recover the relation between Nature and the City. These includes the creation of new parks, squares and green corridors and the improvement of existing green areas including the rehabilitation of a 370 hectares big urban reserve located down town. In scarcity times of remnant areas with potential to become parks, as well as money that can be applied to the creation of new spaces, the local administration should make possible that vacant private lots could be at least temporarily used as new green community spaces. These could be designed, built and managed by NGOs, schools, universities, groups of pensioners, etc., devoted to urban agriculture or environmental education until the owner decides the lot construction. When this happens the builder should mitigate at the place the loss of nature with green terraces or walls. Buenos Aires’ strategy is to connect new and existing public green space through a structure of green corridors is adequate, because it regenerates permeable urban surface and increase biodiversity. Nevertheless, the attention should be placed not only on trees, but on shrubs, herbs and vines to preserve the Pampas ecoregion characterized by herbaceous components. This could apply to covered part of the sidewalks in order to increase groundcover today nonexistent in the city.

about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director.

David Maddox

I was in a meeting a few months ago and someone put up a picture of a bioswale and said: “What’s this? It’s not a park. It doesn’t function like one!” Well, the bioswale is functioning exactly as designed: to collect stormwater. It does other things too, such as be a pretty patch of green and support biodiversity. But my colleague, who is a design professional, wasn’t aware of this. Many of us agree that nature in cities is good for cities and people. Biodiversity and nature provide formal ecosystem services and less tangible biophilic services. The professionals — mostly — know this. We have made the case less well with urban dwellers more broadly, who are rightly concerned about jobs, safety, transportation, livability, walkability and so on, maybe in that order. Many, even most, think of nature as irrelevant to their everyday lives. Others think of nature as “somewhere else”. To me, the single most important need isn’t in science, but in communication. We need to better make the connection between people and urban nature. Such awareness would trickle sideways to other residents, upwards to policy-makers, and akimbo to design professionals. How do we do it? We need to collaborate more with artists, exhibit designers, and media minds to make real use of demonstration projects, art installations, and pop-up messaging. How about a pop-up demonstration ecosystem in a city square? Paris’ City Hall did one recently. Washington, D.C. storm drains have painted signs that tell you that the site is part of the Chesapeake Bay drainage. How about a sculpture of a fish swimming through a building, as in Portland? How about an explanatory sign on the bioswale? Most fundamentally we need not to just “educate”, but engage, to find ways to reach beyond the groups we usually talk to and expand the dialog to include people who might not see things the same way. To do this we’ll have to find new ways to communicate, and find new collaborators outside our disciplines, and maybe outside our comfort zones.

about the writer

John Kostyack

John Kostyack is VP for Wildlife Conservation at the National Wildlife Federation. His focus is restoring ecosystems to help reduce harmful climate change impacts. FULL BIO

John Kostyack

Resiliency is the Hallmark of Local Leadership, Wildlife conservationists should celebrate leaders, such as those in Curitiba, Brazil, who have achieved conservation results under the banner of sustainability. Champions of sustainability measure their success by the triple bottom line of environmental, economic and social progress- an approach to conservation more likely to produce fair and politically-viable outcomes that one focused solely on biodiversity. That said, sustainability no longer quite captures what is most needed in today’s urban environments. Today, the most important idea for advancing conservation in the city is resilience. Resilience – making people, communities and systems better prepared to withstand catastrophic events- incorporates all of the concepts of sustainability while highlighting the need to confront the looming threat of climate change. In the past decade, we have seen disasters such as Superstorm Sandy and Hurricane Katrina send shock waves through U.S. cities. Yet many refuse to acknowledge that these extreme weather events are part of the “new normal” of rapid climate change. This denial of climate change reality puts both people and wildlife at great risk. Adopting resiliency as the new hallmark of local leadership would help reverse this dynamic. Leaders would be expected to know the most effective strategies for coping with intensified heat, drought, floods and storms. They would need to know how to rebuild oyster reefs, wetlands and other natural features to protect communities from harmful climate change impacts while supporting healthy fish and wildlife populations. Greater attention to resiliency and climate-related risks would also lead urbanites to become stronger advocates for forward-thinking climate policy. On their agenda would be two ideas essential to the future of their cities: a tax or similar market-based limit on the carbon pollution driving climate change and, under the principle of “polluter pays for its damage,” a requirement that at least some of these tax revenues be used to help cities cope with inevitable climate-related disasters.

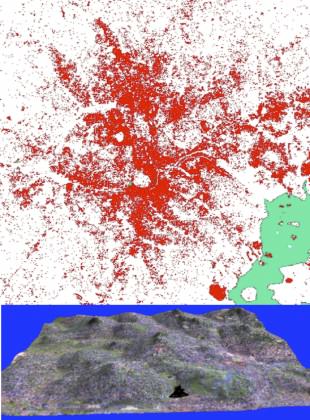

Urban nature and biodiversity

Urban nature and biodiversity

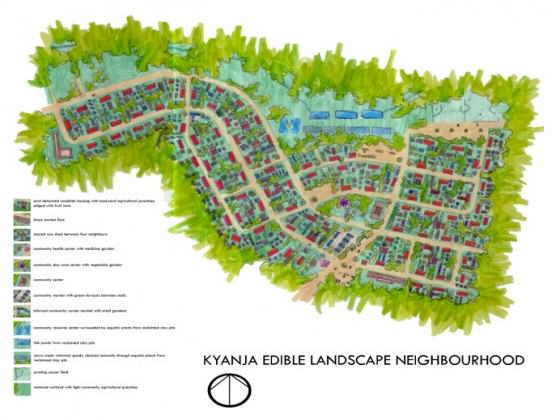

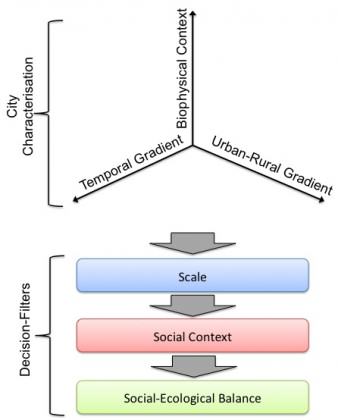

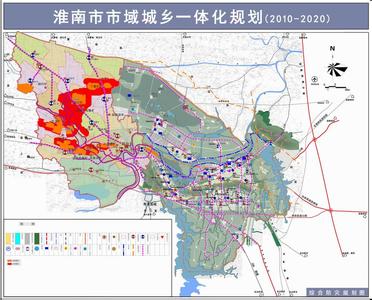

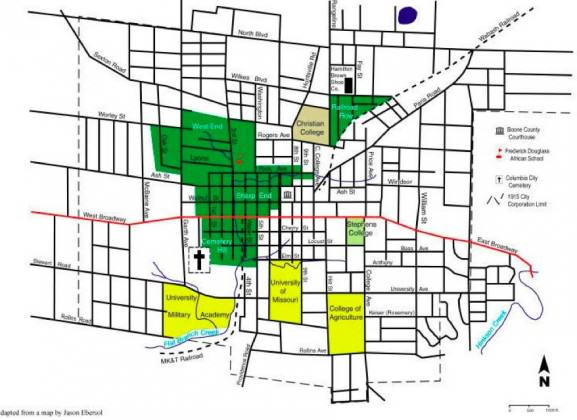

Urban-Rural integrated planning

Urban-Rural integrated planning

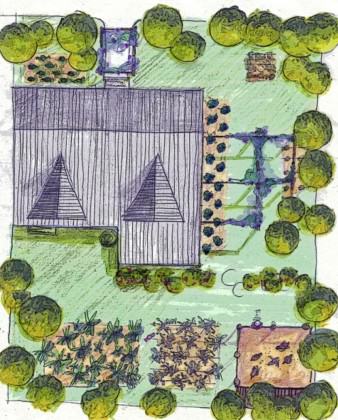

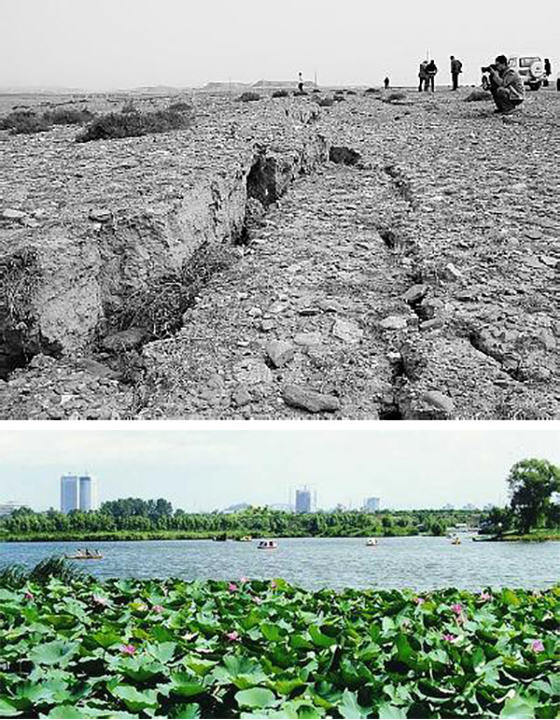

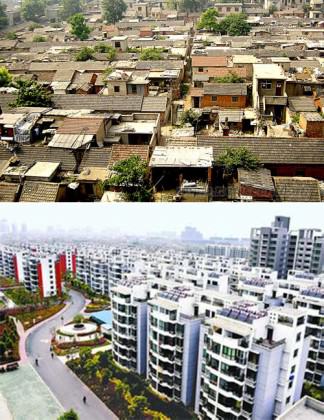

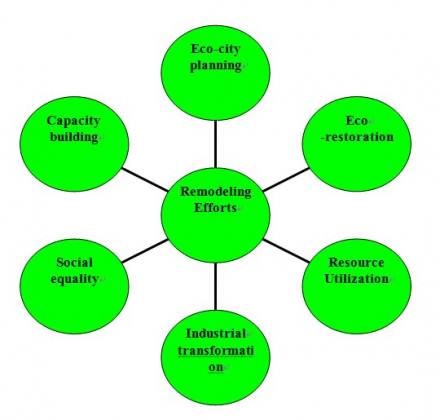

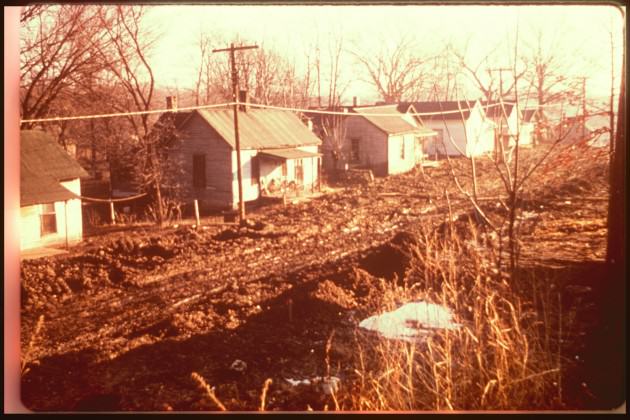

Slum reconstruction

Slum reconstruction

At

At

Where can you get more information?

Where can you get more information?

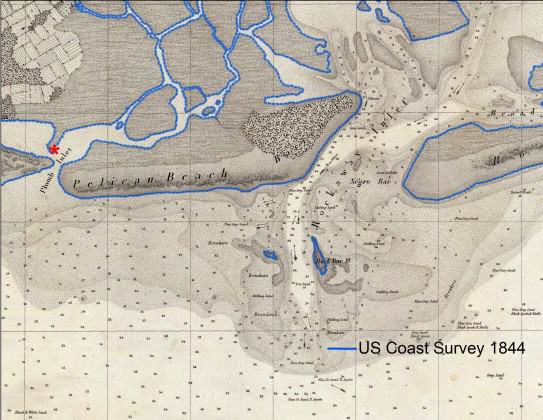

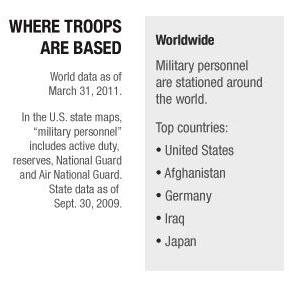

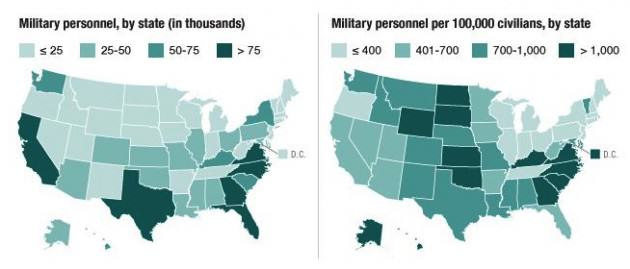

As of a couple of years ago, there were 2,266,883 people serving in the U.S. military, many of whom serve on bases in the U.S. or abroad. The majority of Active Duty members (86.5%) are stationed in the United States and U.S. territories. The next largest percentages of Active Duty members are stationed in East Asia (7.1%) and Europe (5.8%). The largest base in the US is

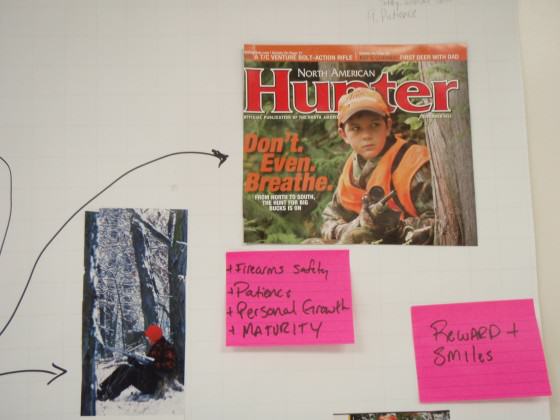

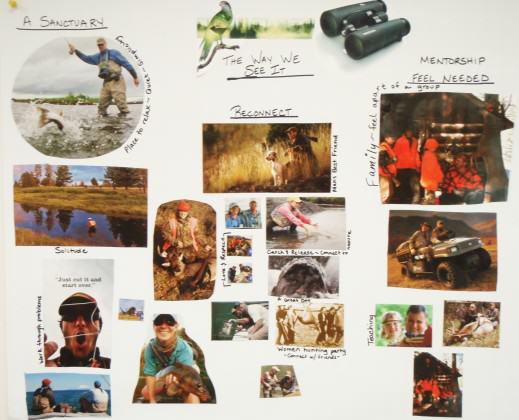

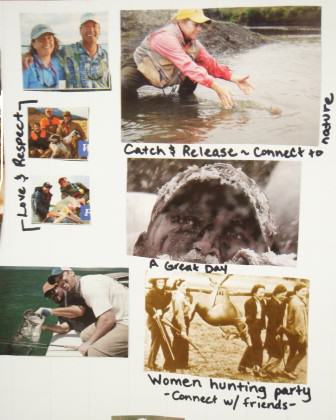

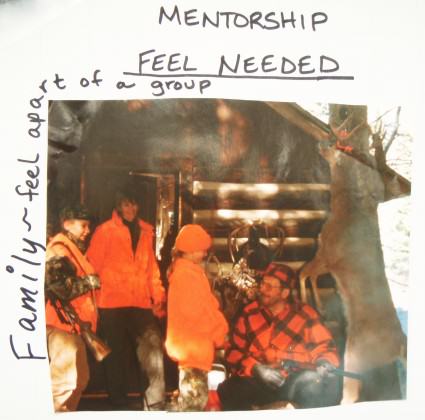

As of a couple of years ago, there were 2,266,883 people serving in the U.S. military, many of whom serve on bases in the U.S. or abroad. The majority of Active Duty members (86.5%) are stationed in the United States and U.S. territories. The next largest percentages of Active Duty members are stationed in East Asia (7.1%) and Europe (5.8%). The largest base in the US is  The benefits of human-nature interaction as a form of therapy are well documented. However, the value of human-nature interaction for returning combat veterans and their families and communities has been less studied. While administrators in the U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs struggle to design programs to help returning combatants reintegrate into communities, programs started by veterans themselves have emerged in New York State and across the U.S. Notably, many of these programs have a focus on the healing power of interacting with nature through outdoor recreation, including hunting and fishing, and through other restoration and greening activities. Examples include

The benefits of human-nature interaction as a form of therapy are well documented. However, the value of human-nature interaction for returning combat veterans and their families and communities has been less studied. While administrators in the U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs struggle to design programs to help returning combatants reintegrate into communities, programs started by veterans themselves have emerged in New York State and across the U.S. Notably, many of these programs have a focus on the healing power of interacting with nature through outdoor recreation, including hunting and fishing, and through other restoration and greening activities. Examples include

So what have we learned and where do we go from here?

So what have we learned and where do we go from here?

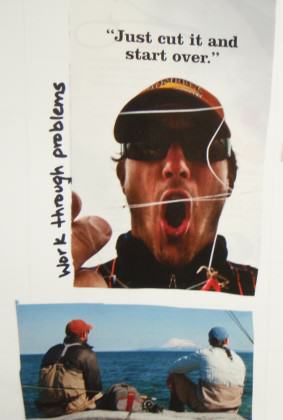

Soldiers returning from long and protracted wars, especially with life altering injuries, often report feelings of inadequacy and of being devalued, and of feeling that their particular skill sets and competencies are not applicable in civilian life. On the other hand, returning veterans that engage in outdoor recreation and restoration activities report significant relief from these and other feelings, sometimes for short periods of time and more often for longer periods. In these reports are suggestions that reveal an intensification and specific manifestation of

Soldiers returning from long and protracted wars, especially with life altering injuries, often report feelings of inadequacy and of being devalued, and of feeling that their particular skill sets and competencies are not applicable in civilian life. On the other hand, returning veterans that engage in outdoor recreation and restoration activities report significant relief from these and other feelings, sometimes for short periods of time and more often for longer periods. In these reports are suggestions that reveal an intensification and specific manifestation of

20 Comments

Join our conversation