My second contribution to the Nature of Cities blog was scheduled to fall around that awkward moment at the start of the New Year when productivity is at its lowest ebb. Instead of sitting down to the task at my own snow-bound desk in upstate New York, I find myself seated on a plastic chair in a poured concrete garage smack-dab in the middle of rural Portugal. The sun is shining through an open door, the flies are buzzing around a stack of old wine bottles in the corner, and a rooster just announced his presence in the yard out back. I’m on vacation, you see, visiting family and spending time in a part of Portugal that has, in many ways, opted out of the networked society that so completely defines my life back in the U.S. There are four channels on my aunt’s television set. No stray WiFi signals show up on my computer. News still travels efficiently by word of mouth, and neighbors pass the time gossiping at the front gate with anyone who passes by.

Being that I’m on vacation, this blog post is less of a watertight exposition on a single topic than a meander through some loosely connected ideas about cities and nature. There’s little around me right now to inspire any reflection on cities, yet there are seemingly endless opportunities to contemplate nature. For miles around, this ancient coastal plain is checkered with allotment farms, pine forests, and opportunistic stands of eucalyptus trees. Much of the rural, self-sufficient lifestyle rhapsodized about in cities back home in the U.S. is unassumingly lived out here, with little conscious thought given to things like environmental sustainability, locally-sourced food, or cultivating a “sense of place.” People grow their own cabbages and onions, potatoes and garlic, and it’s hardly cause for adulation.

Yet this is Western Europe, after all. Rural though the setting may be, the fact remains that these lands have been trampled upon, cultivated, exhausted, fertilized, subdivided, colonized, and conquered millennia. Aside from the wildlife sequestered in a few national parks, little of what the eye beholds here is likely to be “native” in the strictest sense of the word. It’s all been shaped, to one degree or another, by human hands with the purpose of serving human needs and fulfilling human dreams. It may look like nature, but the landscape was irrefutably drawn by social and cultural forces.

This problem of defining and delimiting nature – especially when it comes to nature and cities – has bubbled up in more than one contribution to this blog since its inauguration. My first post last July dealt with the idea of cities as cyborgs, collections of artificial and natural materials and processes inextricably fused together to form urban settings. In August, Brian McGrath introduced the idea of a “nature-culture continuum,” urging us to go beyond simply finding examples of nature in cities (trees, green spaces, animals, etc.) when we speak about the nature of cities. More recently, Stephanie Pincetl helped us see the city’s built infrastructure, crafted from stone and steel, as an important part of any conversation about green infrastructure and sustainable urban living. Put another way, Pincetl encourages us to recognize and value the inanimate dimensions of urban nature, though we tend to focus on biological systems in these discussions. For the remainder of this week’s post, I want to consider this emphasis on biological systems in our discourse on the nature of cities.

In his introduction to Uncommon Ground, a pioneering collection of essays published in the mid-1990’s, environmental historian William Cronon made an exhaustively strong case for critically deconstructing the seemingly fixed concept of nature. Cronon and his colleagues argued that the idea of nature couldn’t be taken for granted, its definition assumed to be universal or everlasting. Nature, it turned out, is a slippery concept. Though Cronon’s task was deconstruction, his aim was, in the end, the creation of a more stable conceptual footing for the modern environmental movement. I’ll let him speak for himself:

“… our essays may be perceived by some as hostile to environmentalism, part of a general backlash against the movement. And yet nothing could be further from the truth. Indeed, it is precisely because we sympathize so strongly with the environmental agenda – with the task of rethinking and reconstructing human relationships with the natural world to make them more just and accountable – that we believe these questions must be confronted. To ignore them is to proceed on intellectual foundations that may ultimately prove unsustainable.”

Most of the essays that comprise Uncommon Ground ask us to think twice whenever we turn to nature for solutions to human problems. It’s not that nature doesn’t offer valuable lessons. Yet our ideas of nature are inevitably cultivated from our cultural assumptions and prejudices. When we look at nature, we can’t help but see it through a distorting cultural lens. For humans, nature is something like a story to be told (and re-told) rather than objective reality that can be exhaustively understood on its own terms. When we look to nature for inspiration in tackling urban problems, we need to carefully consider how much of that inspiration actually comes from a tacit set of human values and beliefs. Nature, it would seem, is what we make of it. What, then, do we make of cities designed in nature’s image?

The idea that nature offers untapped solutions for urban problems is not entirely new. At least a century ago, the Garden City movement called for cities that more closely resembled the countryside, with lower population densities and more acreage given over to green space. The same planning ideas would live on, albeit distortedly, in the form of Modernist “towers in the park” – an urban design strategy familiar to anyone who’s spent time in a North American housing project or a French banlieue.

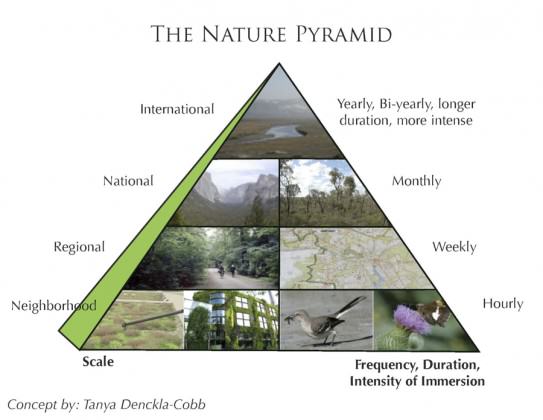

In recent years, the concept of biophilia has inspired some efforts to make cities more livable and sustainable. I n his blog post earlier this year, Tim Beatley described biophilia as the notion “that we are hard-wired from evolution to need and want contact with nature.” There are two concepts at play in Beatly’s description. First, there’s the core notion of biophilia, an experience of love or attraction to living biological systems. Then there’s the biophilia hypothesis, first put forward by the celebrated biologist E.O. Wilson in 1984. The hypothesis posits that human beings, having spent much of their evolutionary development as a species in nature, are inherently drawn to natural settings. Designing a city with biophilia in mind means making space for nature, however one defines it.

On the face of it, this would seem to be a common-sense approach to solving some of the environmental ailments found in contemporary cities. Yet creeping in the background is all that stuff from William Cronon (and others) about the slipperiness of the concept of nature – especially when it comes to determining what is and isn’t “natural” in cities. Is nature just “the green things” that we find in cities? The parks and trees and rivers and shrubs and everything else that wouldn’t be out of place in a rural setting like the one I find myself in right now? Or are even the most developed cities already natural places, regardless of how artificial they seem? Eric Sanderson made a fine case for moving past this dichotomy in his post earlier in the year, helping us “conceive of cities in their entirety as ecological places.” Yet if cities are already quite natural on their own, where does that leave the biophilia hypothesis as a prescription for environmentally sustainable and livable cities?

I want to offer three short – and, admittedly, incomplete – observations that I hope will spark further conversation around these themes. I’ll keep my points brief, mainly because I’m not resolutely devoted to them and I’m curious to hear what others have to say in response to each general idea.

Biomimicry beyond biophilia?

Biomimicry is the idea that natural processes may hold within them the blueprints for engineering sustainable human technologies. Examples abound, from sewage purified in ersatz “living machine” wetlands to synthetic fibers spun in factories with as little impact as a spider weaving its web. Biomimicry promises a future where the materials of an industrial civilization leave no more of a lasting trace on the earth than the objects in a neolithic hunter-gatherer’s toolkit. Janine Benyus’ Biomimicry and William McDonough’s Cradle to Cradle are both must-read primers for anyone interested in learning more.

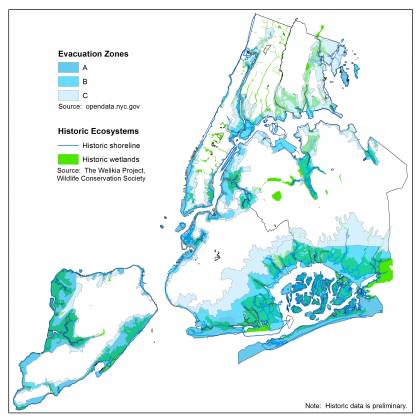

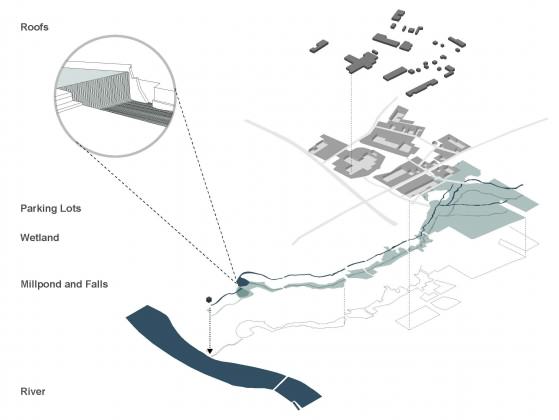

All cities rely on technology. Their infrastructures are a complex tangle of human life-support systems, and like any cluster of technologies, they may be made more sustainable through biomimcry. We might think of “green infrastructure” as low-hanging fruit; a kind of first pass, low-tech approach to biomimcry for urban technology. Instead of re-engineering a sewage treatment plant to function like a wetland, just create a wetland. In the process, you’ve created a place for humans to experience a biological system within the city. Green infrastructures are where the concepts of biomimicry and biophilia overlap.

However, there remain countless technologies and industrial materials that don’t readily lend themselves to a green infrastructure alternative, all of them integral to the daily function of contemporary cities. Moreover, in dense mega-cities, green infrastructure may not be able to carry the burden of tens of millions of people, and you’d be hard pressed to plunk down a wetland in the middle of Manhattan. In these instances, it seems to me, biomimicry trumps biophilia. Build a sewage treatment plant, and design it to function as much like a wetland as possible, drawing on whatever science tells us about how wetlands work. The two ideas aren’t mutually exclusive, but there’s a continuum of feasibility that needs to be appreciated.

Sociobiology – biophilia’s conceptual underpinning – is a contested idea

The biophilia hypothesis grew out of sociobiology, a field of research predicated on the idea that human behavior and culture are products of the biological evolution of the species. Like biophilia, the field owes its development to E.O. Wilson, who set down the parameters of sociobiology in the mid-1970’s. Sociobiology held out the promise of synthesizing the natural and social sciences for a comprehensive approach to understanding humankind. However, the field was not without its detractors. No less an authority than evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould would, along with others, criticize sociobiology as a narrowly “deterministic view of human society and human action.”

There isn’t enough space on this blog to rehash the many debates that followed Wilson’s publication and Gould’s critique. My point here is simply to emphasize that sociobiology, which gives the biophilia hypothesis its underlying logic, is not a universally accepted approach to understanding humankind. In fact, the debate continues to this day, with significant arguments against sociobiology coming from scholars across the social sciences. Yet in many of our efforts to draw on the biophilia hypothesis to create greener cities, we treat the concept as an established fact. I won’t take a stand one way or another right now, but I do think we need to let the debate into our discourse on the nature of cities in order to make our work more resilient, rigorous, and, ultimately, more relevant.

Is biophilia bigger than “Nature”?

If we hold the biophilia hypothesis to be true, then what are the qualities of biological systems and “natural” settings that make them so attractive to humans? How do we evaluate an urban setting to determine whether or not it adequately answers to the biophilia hypothesis? How does the human eye – and the human heart – tell nature from its own creations? Does a hardscrabble community garden make the cut? A lonely street tree? What if it’s an Ailanthus, that much-reviled invasive plant that thrives so comfortably in cities? We’re back to that issue of defining nature, in all its slipperiness, in order to better understand biophilia in cities.

As a result, I struggle with how nature is defined when the biophilia hypothesis is applied to urban planning and design. I have a hard time lumping a single tree, a community garden, a wetland, a window box, a green roof, a flock of birds, an urban park, or any number of other phenomena all into the same category. And, despite contradicting myself, I also wonder we’ve taken too narrow a view of the things that trigger a biophilic response in cities. If a garden can elicit a feeling a biophilia, why can’t any other object of beauty crafted by human hands? If we celebrate the presence of nature in cities because it provides unique opportunities for surprise, wonder, and reflection, what other aspects of urban living fulfill those needs? I personally feel the same magnetic pull from a technicolor graffiti mural as I do from a well-designed park or a lovingly maintained garden. All three grab the eye with the visual equivalent of a complex polyrhythm. All three are vibrant expressions of life, human and non-human alike.

What might we discover if we keep pushing the boundaries of biophilia, including more and more things that don’t normally show up on a list of “natural” phenomena? How would our notion of the biophilia hypothesis change? What would urban design and landscape architecture have to add to the conversation, given their focus on creating vibrant and interesting public spaces within cities?

This blog post started with me reflecting on my rural surroundings in central Portugal. By the time I got to putting down this last sentence, I had relocated south to Lisbon to spend the rest of my vacation with friends in the capital city. As my train pulled into the riverside terminal last night, I couldn’t help feeling relieved to find myself back in an urban setting. I was bored in the countryside, uneasy and out of place. Beautiful though it may be, uninterrupted nature is not for everyone. Maybe neon lights and street art and sidewalk benches packed with people from all walks of life have a place in our understanding of biophilia, too.

Philip Silva

Ithaca, NY USA

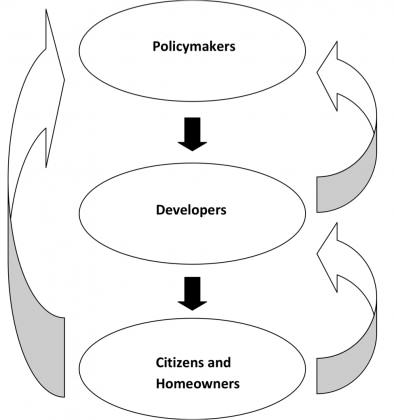

While a biodiversity practitioner’s effect is limited to some extent by their position, a politician is constrained more by their need to address a number of often-conflicting issues, and to satisfy their constituency. This also has quite a lot to do with personality but it’s more about awareness and subsequent willingness. If politicians have the will to support biodiversity, biodiversity practitioners are likely to be given considerable freedom in their work and, just as importantly, more likely to be able to access municipal funding. On the other hand if a politician has taken a stance in opposition to biodiversity, for example if they consider it to do nothing but impede development, then very little will be achieved by even a well-staffed and well-integrated biodiversity unit. Even the neutral politician can be restrictive because, when biodiversity comes up against other priorities, the likelihood is that this decision-maker will know and care more about a new road or housing development than about a concept with which they are less familiar.

While a biodiversity practitioner’s effect is limited to some extent by their position, a politician is constrained more by their need to address a number of often-conflicting issues, and to satisfy their constituency. This also has quite a lot to do with personality but it’s more about awareness and subsequent willingness. If politicians have the will to support biodiversity, biodiversity practitioners are likely to be given considerable freedom in their work and, just as importantly, more likely to be able to access municipal funding. On the other hand if a politician has taken a stance in opposition to biodiversity, for example if they consider it to do nothing but impede development, then very little will be achieved by even a well-staffed and well-integrated biodiversity unit. Even the neutral politician can be restrictive because, when biodiversity comes up against other priorities, the likelihood is that this decision-maker will know and care more about a new road or housing development than about a concept with which they are less familiar. The problem with both personalities and politicians is impermanence. While both represent very worthwhile mechanisms for maintaining a focus on biodiversity considerations, they do unfortunately come and go. This is especially true for the latter and necessitates a constant process of relationship-building which can be especially tricky when a new administration abhors the old, and may even get rid of officials associated with it. As an additional and supporting measure policy is, therefore, critical. It, too, can be changed over time depending on the administration but can provide an additional safeguard. Even if a new administration is bent on changing or removing it, the due process required may at least buy some time to win them over.

The problem with both personalities and politicians is impermanence. While both represent very worthwhile mechanisms for maintaining a focus on biodiversity considerations, they do unfortunately come and go. This is especially true for the latter and necessitates a constant process of relationship-building which can be especially tricky when a new administration abhors the old, and may even get rid of officials associated with it. As an additional and supporting measure policy is, therefore, critical. It, too, can be changed over time depending on the administration but can provide an additional safeguard. Even if a new administration is bent on changing or removing it, the due process required may at least buy some time to win them over.

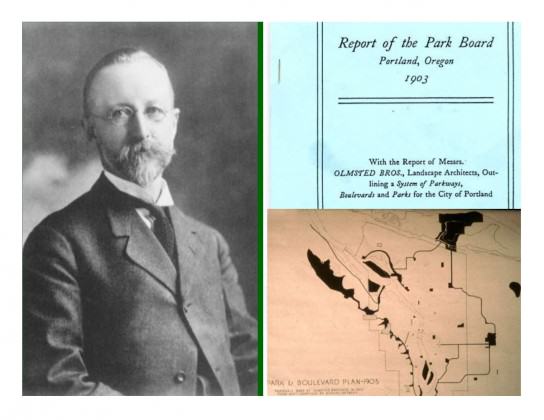

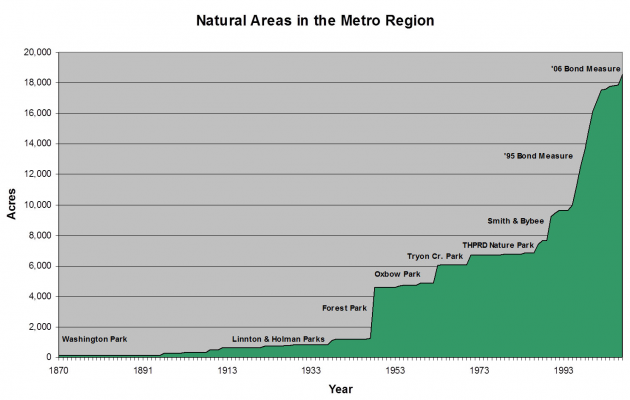

Three years later Metro adopted the

Three years later Metro adopted the

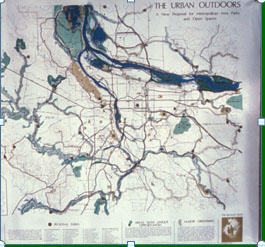

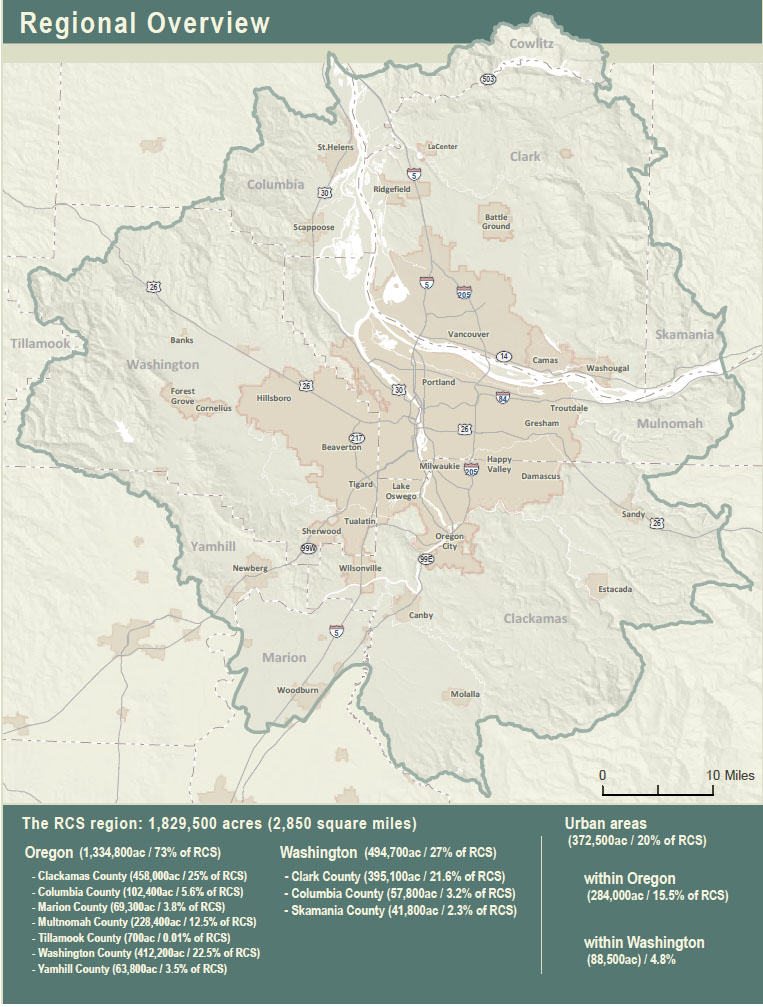

In 2010 The Intertwine Alliance launched the

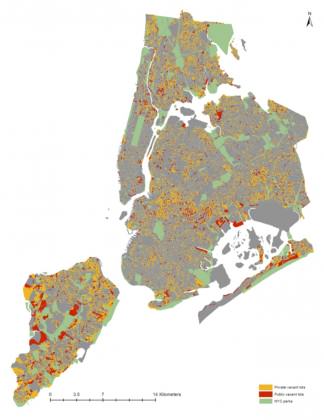

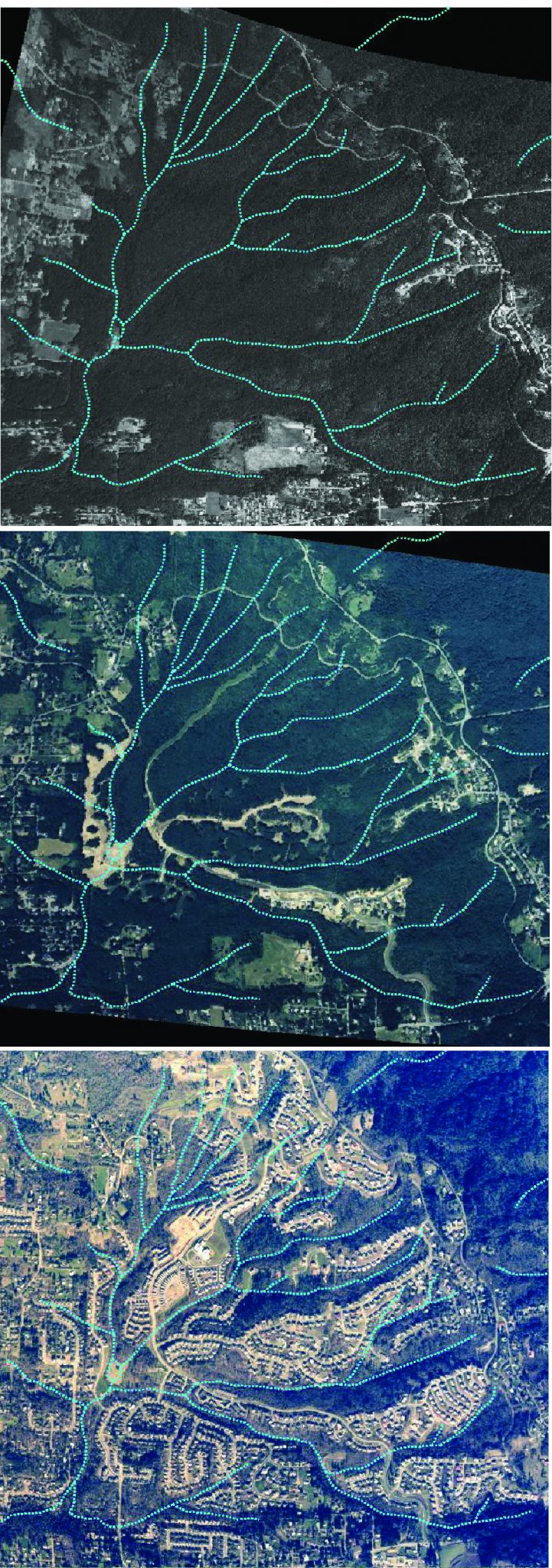

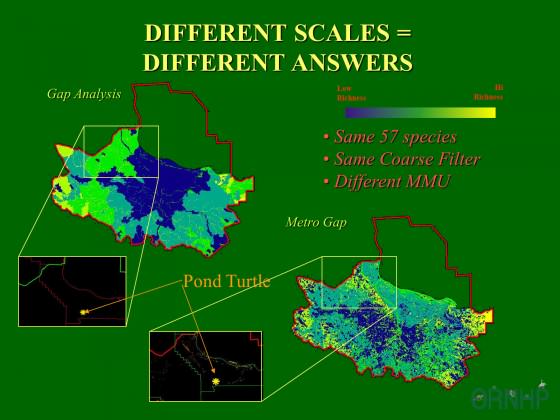

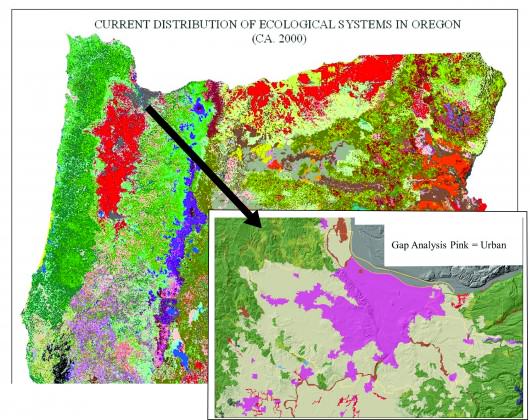

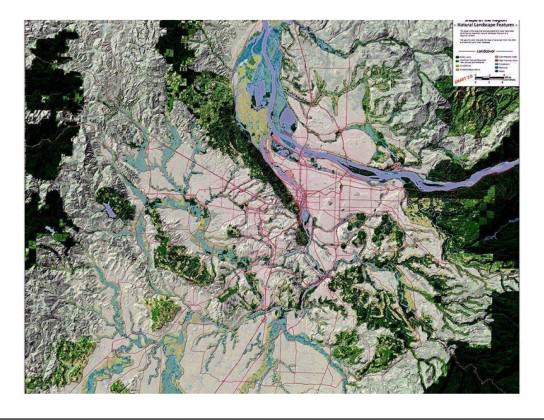

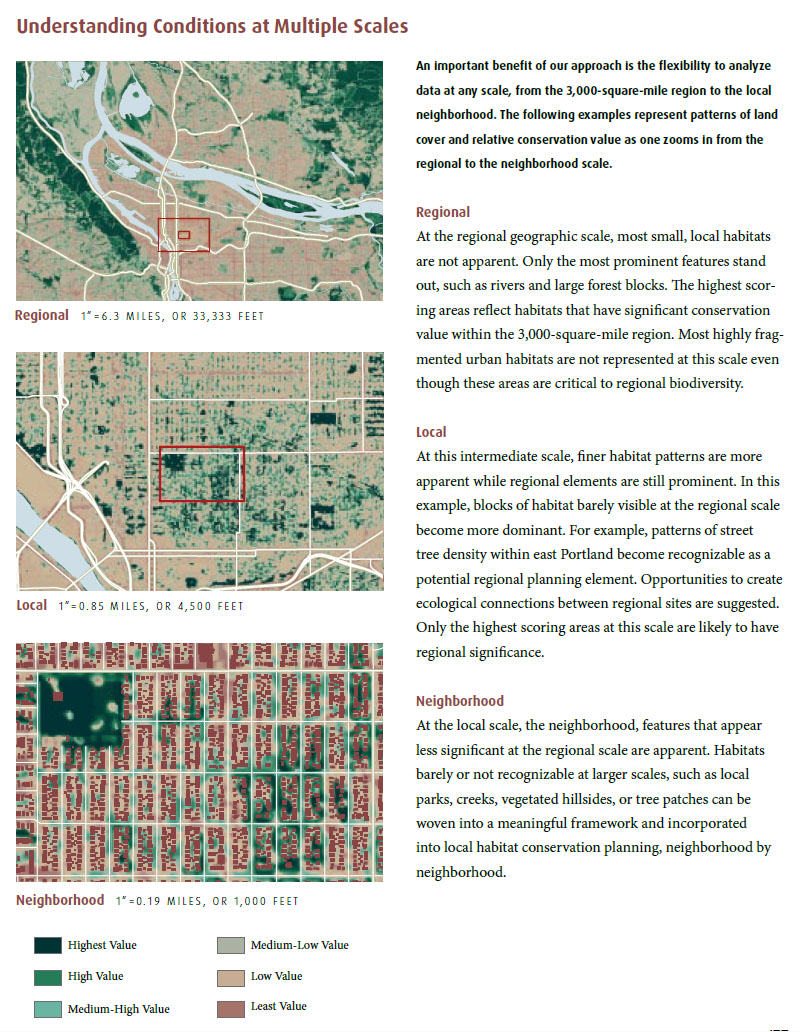

In 2010 The Intertwine Alliance launched the  In any mapping effort the issue of database size is a critical factor. In our region, while we have imagery at the one-half meter resolution most regional mapping efforts have been at 30-meters or larger resolution, which is fine if all your are interested in is characterizing an ecoregion. If, however, you are interested in both the ecoregion and urban core higher resolution is required.

In any mapping effort the issue of database size is a critical factor. In our region, while we have imagery at the one-half meter resolution most regional mapping efforts have been at 30-meters or larger resolution, which is fine if all your are interested in is characterizing an ecoregion. If, however, you are interested in both the ecoregion and urban core higher resolution is required.

I am utterly convinced the way forward is dependent on creating working models of “green” developments, from whole subdivisions to individual yards, in each county and neighborhood across the country. Do not underestimate the power of a local example. Nothing speaks more to increasing the uptake of alternative designs and management practices than examples that people can see and discuss. I have found building that first, local green subdivision helps to showcase green development practices and provide a catalyst for future developers to adopt new practices. To help promote biodiversity conservation in subdivision development, I recently have written a book titled,

I am utterly convinced the way forward is dependent on creating working models of “green” developments, from whole subdivisions to individual yards, in each county and neighborhood across the country. Do not underestimate the power of a local example. Nothing speaks more to increasing the uptake of alternative designs and management practices than examples that people can see and discuss. I have found building that first, local green subdivision helps to showcase green development practices and provide a catalyst for future developers to adopt new practices. To help promote biodiversity conservation in subdivision development, I recently have written a book titled,

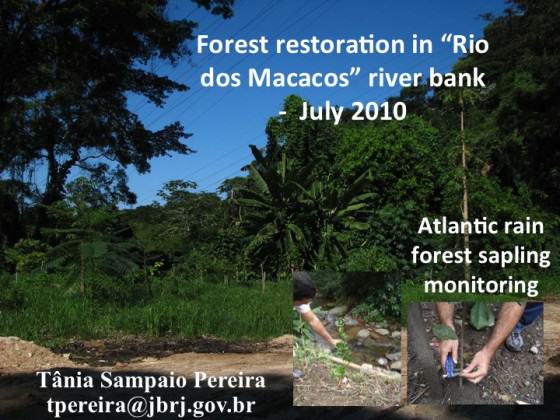

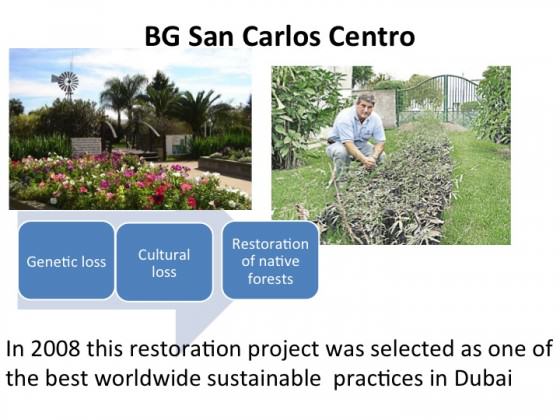

A similar project for the restoration of dry forest was implemented by the

A similar project for the restoration of dry forest was implemented by the  The BG of the

The BG of the  Many BGs are involved in programs concerning street trees. While in

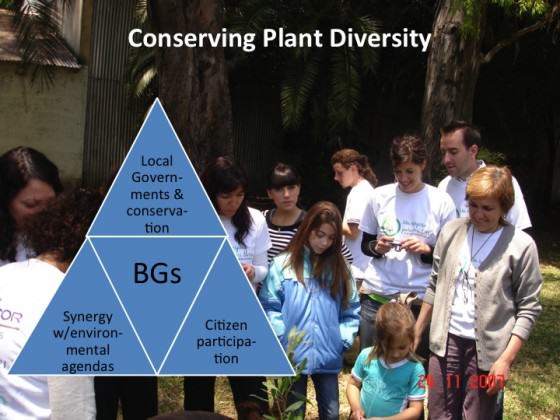

Many BGs are involved in programs concerning street trees. While in  The examples described above show that Latin American and the Caribbean BGs are working on an integrated model of multiple dimensions and generate an urban landmark able to create synergies between the exurban and urban environment. Among the dimensions that BGs address should be mentioned the promotion of culture, including environmental rehabilitation of urban and architectural heritage of their buildings, the conservation and management of biodiversity, the generation and transfer of environmental knowledge and policies for social and economic development as inevitable companions of all dimensions. In so doing they have adopted a partnership approach at both the local and national level between actors of different natures, which explains the possibility of taking action with relatively small budgets.

The examples described above show that Latin American and the Caribbean BGs are working on an integrated model of multiple dimensions and generate an urban landmark able to create synergies between the exurban and urban environment. Among the dimensions that BGs address should be mentioned the promotion of culture, including environmental rehabilitation of urban and architectural heritage of their buildings, the conservation and management of biodiversity, the generation and transfer of environmental knowledge and policies for social and economic development as inevitable companions of all dimensions. In so doing they have adopted a partnership approach at both the local and national level between actors of different natures, which explains the possibility of taking action with relatively small budgets.

3 Comments

Join our conversation