ESSAYS | POINTS OF VIEW

-

Art That Moves Cities: How Creativity Revives Place and Spirit

I stood on a hillside in the Comuna 13 neighborhood of Medellín, Colombia, where color burst from walls and rhythm pulsed through alleys. Once infamous for violence, this…

-

Teaching Environmental Politics During the Trump Presidency

When I was offered a full-time, tenure-track position in environmental politics just out of graduate school, I was elated. My research on disaster response, environmental stewardship, and community…

-

How We Miss Half of Wildlife: On the secret world in front of your doorstep

The following is an extended excerpt from Living Night by Sophia Kimmig. For years, I went about my life without noticing it, the dark world. I never gave…

TNOC’S MISSION

Cities and communities that are better for nature and all people, through transdisciplinary dialogue and collaboration.

We combine art, science, and practice in innovative and publicly available engagements for knowledge-driven, imaginative, and just green city making.

search tnoc

ROUNDTABLES | GLOBAL DISCUSSIONS

MORE VIEWS | FROM THE ARCHIVE

SUPPORT BETTER CITIES,

JOIN OUR NETWORK OF DONORS…

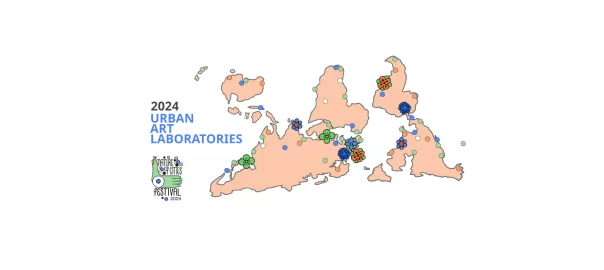

PROJECTS | ART, SCIENCE & ACTION, TOGETHER

NBS COMICS: NATURE TO SAVE THE WORLD

26 Visions for Urban Equity, Inclusion and Opportunity

Now a global project with over ONE MILLION readers, we invite comic creators from all over the world to combine science and storytelling with nature-based solutions (NBS).

JOIN THOUSANDS OF READERS

AROUND THE WORLD…

MORE TNOC PROJECTS | ART, SCIENCE & SOCIAL JUSTICE

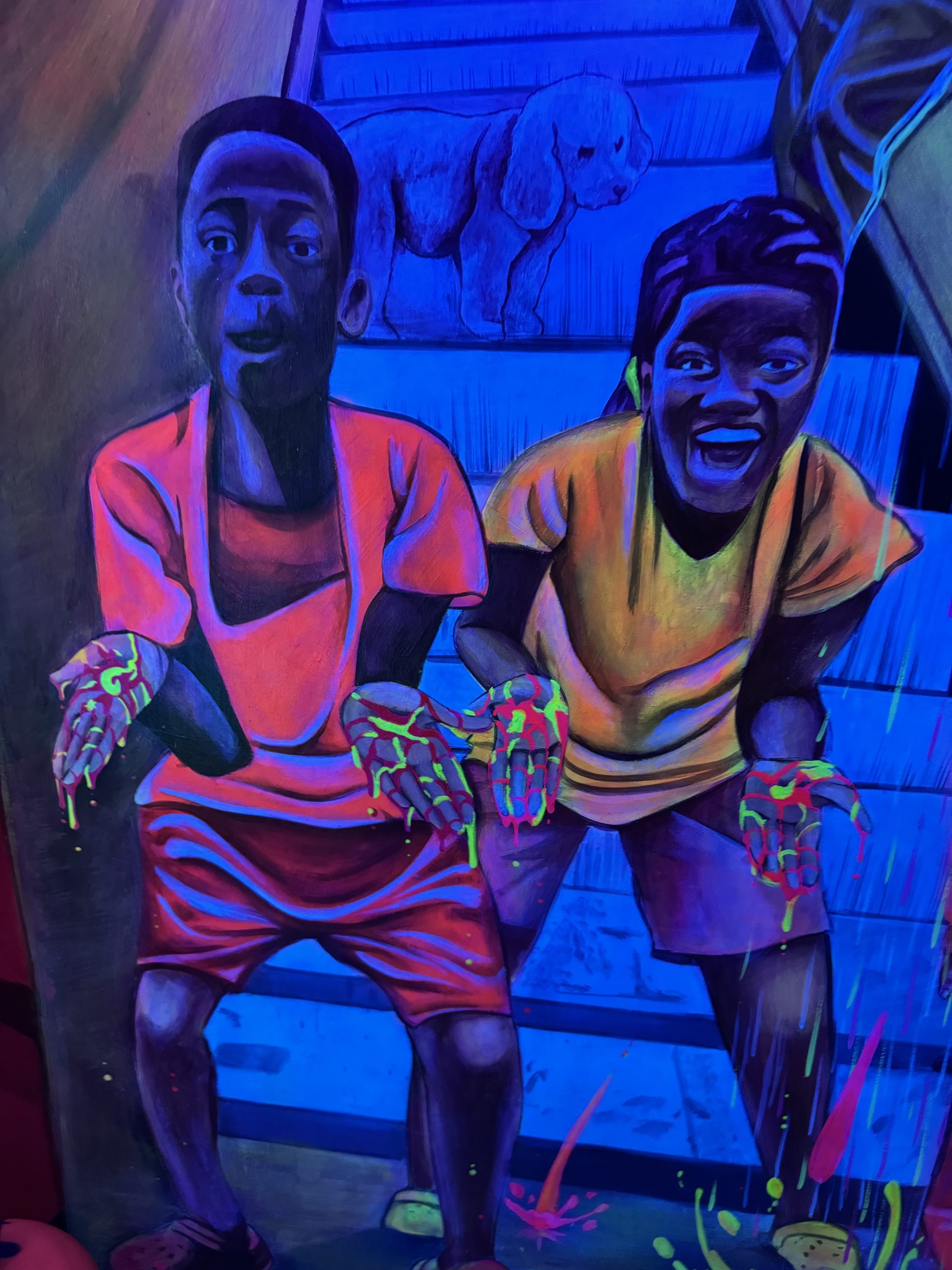

THE NATURE OF GRAFFITI

This is the nature of graffiti. It facilitates speech. It speaks to us. It stakes claims and makes statements. It tells stories.

The Nature of Cities hosts a public gallery about the graffiti and street art that motivates us in public places.

the roots of cool

As the world warms up, how are you thinking about the role that trees and shade can play in making your city or region livable?

Read and listen to the stories in this global collaboration between The Nature of cities & Descanso Gardens.