My main reason for visiting Paris was to attend The Nature of Cities Summit, an international conference very thoughtfully organized and curated by The Nature of Cities, which could not have been held in a more appropriate place—especially in light of very recent and dramatic evidence of the impacts of climate change and global warming. The realities of climate change have drawn attention to the need to tear down the traditional boundaries between the built and natural environment. Now, the importance of integrating the two into a coherent—if sometimes visually confusing—urban fabric is clear: to deploy nature and natural infrastructure as adaptive tools to address challenges solely the product of human invention.

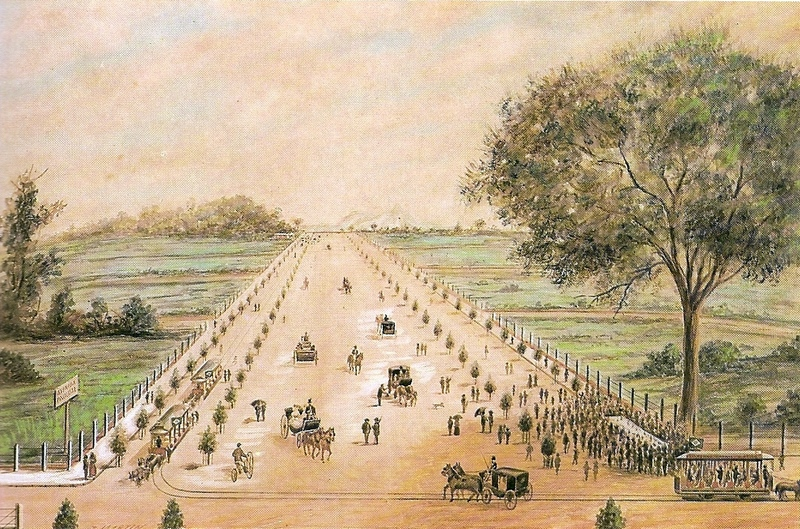

Over the past decade, Paris has led the way in urban greening, creating and renovating new and existing infrastructure to establish itself as a “ville verte”, in addition to its more common moniker as the City of Light. None of this is surprising—Paris’ Mayor, Anne Hidalgo, recently served as Chair of C40 Cities, and of course the critical international climate accord, the Paris Climate Agreement, was signed by 195 countries in the city for which it is named. The city has entered in to collaborative research and policy initiatives with international organizations focused on climate change and urbanism, including C40 Cities and Bloomberg Associates. The strides they have made in taking a city known more for its architectural cohesiveness and street layout than for a preponderance of parks and green spaces in the center city (its two largest parks, the Bois de Vincennes and the Bois de Boulogne, are at the very outer edges of the city) deserve global attention, and provide a template for other cities to follow. Indeed, their example is all the more important in these days of historic heat waves that last longer and hit temperatures never before recorded—Paris and most of Western Europe recently experienced their hottest temperature in recorded history—almost 109°F (42.6°C) in Paris in late July, 2019.

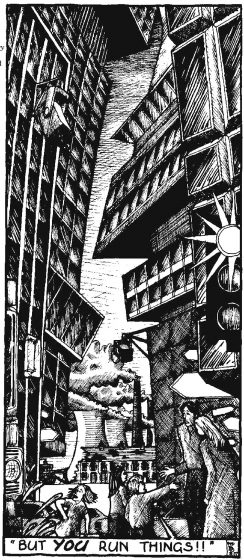

Excessive heat is the deadliest and most ubiquitous of the impacts of climate change, and Paris is one of the global cities leading the efforts and innovations to counter urban heat, and leading the deployment of comprehensive resilience plans devised and implemented to maintain the city’s livability—and basic human survival of extreme weather incidents. High-density, asphalt-laden neighborhoods create “ilots de chaleur urbain”—urban heat islands—that amplify temperatures and keep storm water runoff above ground, worsening flooding. During a prolonged 2003 heat wave, more than 15,000 people died in France—and 40,000 across Europe—from heat-related causes, and, with only preliminary results in, at least 5 deaths were directly related to the recent Paris heat wave. These are some of the challenges created by existing infrastructure—such as black asphalt streets that absorb heat and large expanses of impermeable, tree-less surfaces—that can exacerbate the impacts of climate change. Some cities, such as Paris, are finding ways to rethink, and in some cases, totally reinvent the fabric of their environments to make a strong effort at adaptation.

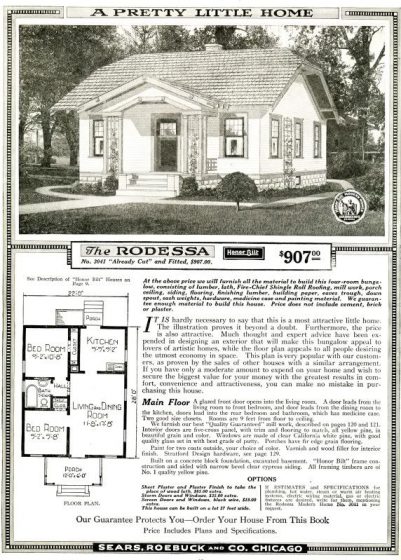

Paris is not alone—other cities have taken aggressive action to green their streets and open spaces. Boston has a quality park within a 10-minute walk of all of its residents, and the current administration under Mayor Marty Walsh continues to prepare its city to prepare for the cascading impacts of climate change effects, while making itself more livable. Washington DC, ranked #1 on The Trust for Public Land’s ParkScore index, grew its investment in its park system significantly, formally adopting the 100% promise to reach 100% park access by 2050. The city already has 98% of its citizens living within a ½ mile of a park, parks that have a varied and extensive array of amenities, and that are well maintained, with parks spending at $270.40 per resident. New York is another leader in green infrastructure, and it is the city that provided the example from which Paris has built, and taken one step further. It is New York’s green schoolyards program, a joint creation of the mayoral administration of Michael Bloomberg and The Trust for Public Land, which Paris has taken as direct inspiration for its own ambitious effort to greatly augment the benefits of schoolyards, which it calls the Oasis Schoolyards Project (Openness, Adaptation, Sensitization, Innovation and Social ties).

The Oasis Project is a key part of Paris’ resilience plan, though under Mayor Hidalgo’s leadership it is just one of a multitude of other efforts aimed at readying the city for both the short-term and long-term climate change impacts. The city’s official plan, adopted in 2017, “Stratégie de Résilience”, locates the challenge at hand in a tradition of change unique to urban environments, while recognizing its immensity. Under this plan and others, the main objectives of the city of Paris include ensuring no resident lives more than seven minutes from a green space by 2020.

Deputy Mayor Pénélope Komitès, a key leader in implementing the plan, and the official overseeing parks in Paris, sat down with me and spoke in-depth about some of its other components, which includes building two new parks that are energy self-sufficient and 30 hectares (74 acres) of new parks and gardens across the city. Some of these parks will be open 24 hours during the summer. This is particularly important, especially in the context of data showing that summer nights are warming faster than days, preventing the human body from naturally regulating its temperature during the nighttime hours.

The goal of the Oasis Schoolyards Project is simple: radically remake the asphalt lots that currently serve as school playgrounds into green, community assets. The City worked with Bloomberg Associates to help prioritize which of the 700 schoolyards to begin transforming into Urban Oases. Bloomberg Associates helped analyze five years’ worth of satellite thermal imagery to create the most detailed map of Paris’ hottest neighborhoods. That data was combined with other environmental and social data to create a digital mapping tool to help identify and prioritize schoolyards for the Urban Oases program.

By the beginning of the 2019 school year, Paris hopes to have thirty schoolyards transformed, and by 2040, they want every school to have an oasis. More than 173 acres (70 hectares) of the city surface are occupied by these schoolyards, underscoring the potential for this program to have positive impacts on the health of not only its young, but all of its citizens, since the oases become open to the public outside of school hours. This is especially important for vulnerable populations, such as the elderly, who are at greatest risk during periods of high heat. Studies show that parks can cool their immediate area by between 7 to 12 degrees Fahrenheit (3.9-6.7 degrees Celsius), and that this cooling radius can extend past the borders of the green space and reduce the temperature of the surrounding neighborhood. Providing nearby parks to cool off in is not a luxury, but a life-saving step cities can take to protect their more heat-vulnerable residents. The oases are designed to have permeable surfaces—a far cry from the current asphalt that absorbs heat and repels water—and more vegetation, in addition to shaded areas, and water features that will both provide entertainment and critical cooling on the hottest of days.

As with all ambitious efforts, the process is as important as the product. The students and adults of each community are included in the planning process as part of a co-design methodology, giving ownership of those spaces to those that know and use them the most, while educating them and spreading awareness on matters of sustainability and environmental mindfulness, which are quickly becoming essential components of the toolkit with which we equip our young to cope with this radically changing climate.

Carine Bernede, Director of Green Spaces and the Environment for the City of Paris, and the leader of the Oasis Schoolyards Project, also briefed me on a number of smaller scale initiatives aimed at greening the city. These smaller projects, such as the city’s “rues végétales,” what we call in the US “green streets,” are quickly implemented, intuitive, and achieve impact without major impact on public funds. Implemented at scale across the city, the rues végétales have the potential to clean polluted air, absorb storm water, and bring nature into the heart of the city. Some of these are city-managed improvements that turn blank sidewalks into green corridors that capture storm water runoff and add shade trees to cool the street, others are citizen-sparked greening of tree pits or odd corners of sidewalks.

Paris is also deploying urban agriculture to further green the city, mostly on roofs and parking lots. Usually done in partnership with museums, social organizations, schools, libraries, and other institutions, some projects are community-led and maintained, with special permits given to residents to have their own neighborhood “farms.” In an effort to spread the practice’s adoption, the city is streamlining the bureaucratic channels required for approval of permits. Individuals are able to fill out an application online to initiate and manage their own greening projects and get approval in a few days. There are, of course, some rules, including no pesticides being used, but in general, the process is easy and meant to encourage residents to be co-stewards of their environment. If the sites are deemed to be lacking in maintenance, however, the permits can be revoked.

In addition to these smaller-scale initiatives, the city has undertaken and in some cases completed the redevelopment of 8 major “places” to reduce the amount of space occupied by cars, and make them more pedestrian-friendly. Included among the list of redesigned squares are some notable landmarks, such as Place de La Bastille, Place de Nation, and Place du Pantheon. In other spaces, such as adjacent to the Pantheon, the city simply removed traffic lanes and parking areas and replaced them with a “pop-up” sitting area made of repurposed blocks of stone and large wooden benches. Equally audacious has been Paris’ bold moves to remove major traffic arteries from the banks of the River Seine, replacing them with green spaces and paths for cycling, running, strolling, and contemplation. Another ambitious plan is the transformation of about half of the abandoned, mostly below-grade, 30-kilometer (18-mile) freight train line that runs in a circle around Paris, known as “La Petite Ceinture” (“The Little Belt”). Similar to the Paris’s own pioneering adaptive re-use of its elevated freight line as a park, known as La Coulée Verte or the Promenade Plantée, and to other transformations it inspired in the US such as the High Line in New York City, Atlanta’s Beltline, Chicago’s 606, and the planned QueensWay in NYC, this project is adaptively re-using portions of the rail line as a very informal, very wild walking and cycling space, with only modest interventions to get people up and down to the tracks.

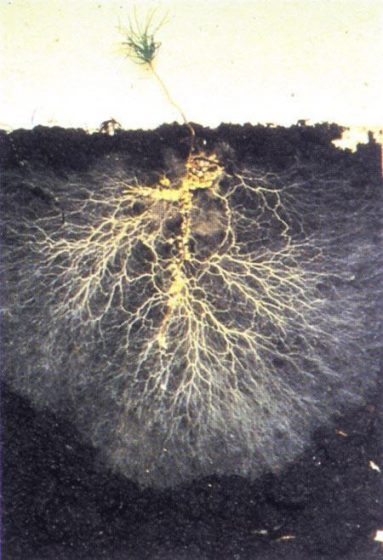

More recently, Paris has announced a plan to plant small forests in open spaces, such as the plazas at the Hôtel de Ville (City hall) and along the Seine. Despite the city’s emphasis on greenery, Paris actually has few trees in comparison to metropolises like New York—500,000 to New York’s 6 million. To augment the urban forest, Paris will add at least 20,000 trees by 2020, many of them in these small woodlands beginning to take root in the city’s open spaces.

Through these many ambitious and innovative efforts, small and large, Paris is working to adapt to the worsening impacts of climate change. By greening the existing infrastructure of the city, and creating new parks and other open spaces, the city is strengthening its capabilities to withstand rising temperatures and more frequent and intense floods, and maintaining its livability even as the planet begins to threaten the healthfulness of urban existence. The recent onset of historic heat waves present major tests to the city of Paris, and these tests will only continue to grow more challenging, which is why it is all the more important Paris pursues and exceeds the goals the city has set for itself—and serves as a model for the rest of the world.

Adrian Benepe

New York

…with additional writing and research by Thomas Newman, National Programs Coordinator, TPL

1 Comment

Join our conversation