Jane Jacobs’ final chapter of Death and Life of Great American Cities, titled “The Kind of Problem a City Is”, remains its most misunderstood. The principal ideas of the book have become the mainstream of urban know-how and helped the triumphant turnarounds in the fortunes of American cities, most notably for New York City. But the last idea in the book—that the scientific foundation that is the basis of the planning profession is founded in error—has not had the same impact. The debate over the scientific basis of urban planning was set aside.

To explain why, I could refer to Thomas Kuhn’s theory of paradigm shifts, which states that a discredited paradigm, even though no one believes its conclusions any longer, cannot disappear until a new, more effective paradigm appears. But Jane Jacobs already had a proposed paradigm for a science of cities. She described it as a problem of “organised complexity”, much like biology, contrasted with problems of “disorganised complexity” that are tractable with linear statistical modeling, and problems of simplicity, or constant relationships between variables (Jacobs p. 429).

A likely explanation for the remaining mystery is that the tools of organized complexity science had not become mature enough to be relatable to urban planners, while statistical science was a hundred years old.

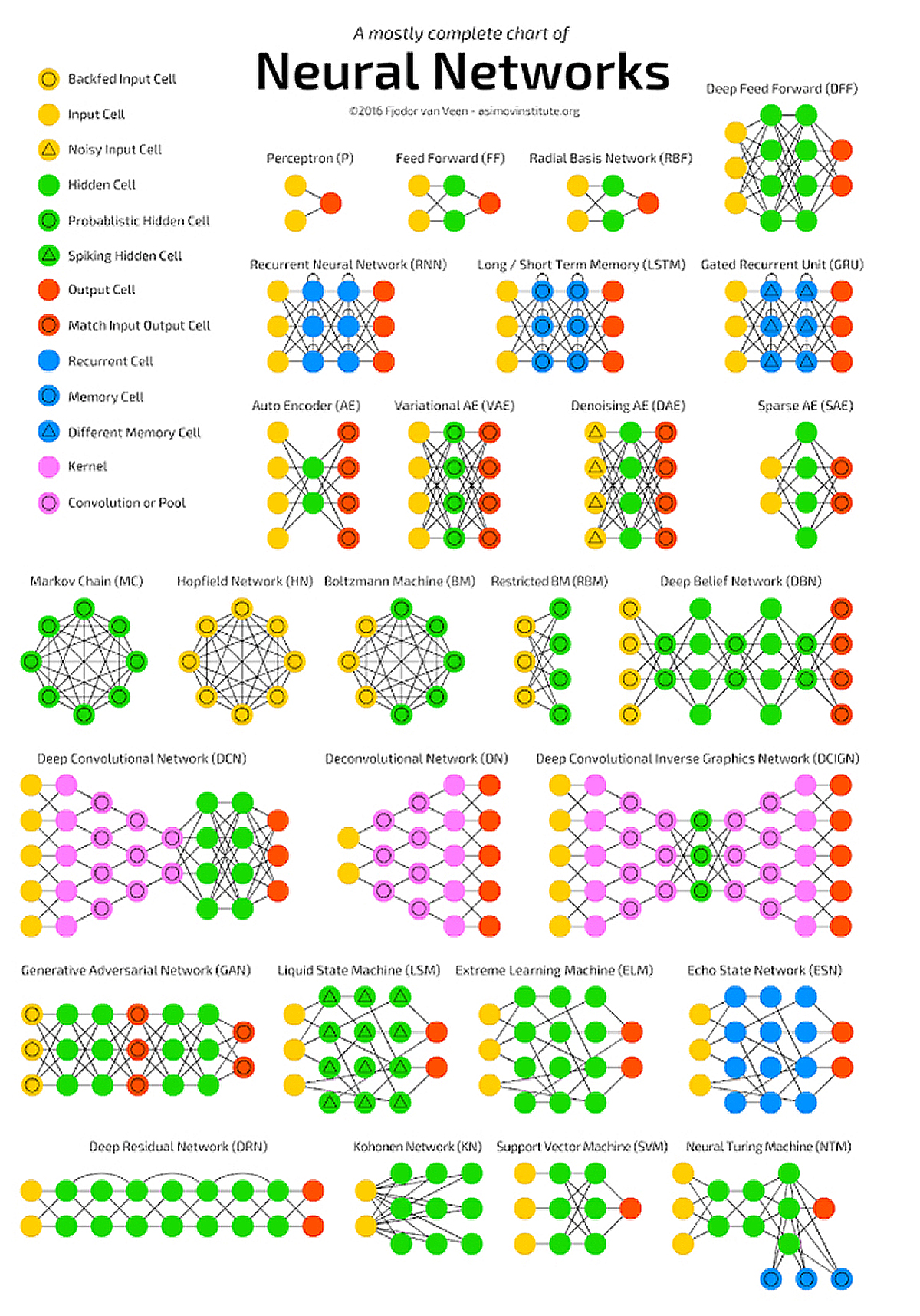

We struggled for decades to express problems of organized complexity in formal mathematics, but recent breakthroughs in computer science have provided models that successfully replicate the behavior of biological neural systems. The artificial neural network is now a workhorse technology for some of the world’s biggest enterprises and should be considered an inspiration from which a science of cities can be built. Before we can explain how let’s first provide an illustration of artificial neural networks and how they are constructed from systems that solve for disorganized complexity and simplicity.

Problems of simplicity

These are the classic two, or three, variable problems that began the scientific revolution. Since Newton was hit on the head by an apple, we have known, among other problems, how to measure precisely how much work needs to go into a device to lift a specific weight, as long as we can measure the weight. That is a linear law between two variables. Another classic expression of a problem of simplicity is e=mc2—once we know the mass of an object, we can derive its potential energy by plugging it into the equation.

What distinguishes problems of simplicity from those more complex are their use of constants—we know precisely how the gravity of Earth affects motion, at the rate 9.807 m/s², and that doesn’t fluctuate over time, though it’s different on the Moon.

Problems of disorganized complexity

These are problems that appear to present random relationships, but that can be tackled statistically and described as an average relationship. For example, when conducting studies on the efficacy of new medicine, the measurements of the results are not precise enough that a single observation can confirm or refute its efficacy. We need to measure a whole population against a control group, and different statistical measures are used to establish whether or not the medicine worked. The most widespread technique for tackling the solution to such problems is called a linear regression. It has successful applications in both science and business.

A linear regression starts from a table of known data points, such as the prices of multiple apartments on the market combined with their area, and whether or not they are in a particular neighborhood. Is it possible to devise a “law” that predicts whether or not an apartment will be in this particular neighborhood if we know only its price and area? Using linear regression, we can estimate the relationship, on average, between these variables, by plugging in different multipliers for the input variables and finding the two multipliers that are the least-wrong over the whole table of known values, meaning they produce the real answer as closely as possible as often as possible. (Different algorithms and techniques exist to produce this kind of result.)

Linear regression, and other such statistical estimation techniques, are the foundations of modern 20th-century science, and are used throughout scientific experiments to verify whether or not results are statistically significant. They are not as reliable as simple linear models, which will never present a significant statistical error in predicting the position of a planet, as one example. Thus, using these techniques implies a tolerance for error and confidence in the value of an average.

Nonetheless, this is what modernist planners thought gave them authority. They knew the numbers and could determine precisely, if not exactly, how much sunlight the average human needed. They believed that if they gathered enough data points, they could solve all the averages in the system, and their policies would be beyond debate, a matter of scientific fact alone.

Of course, people build and live in cities for more than average reasons. There are no average households and businesses, just average measurements. This idea is what Jane Jacobs spent most of her words attacking in her chapter on complexity. Around that same time, the US Air Force conducted a statistical study that proved that there was no average pilot in their service after many pilots crashed because the cockpit, having been designed to average dimensions, obstructed them. The problem was resolved by developing an adjustable seat for the fighter jet, but the ideology of the average has been slow to fade away.

Problems of organized complexity

How can we arrive at a statistical model that accounts for all relevant details, without averaging them over? After Jane Jacobs published her book, computer scientists began exploring a system that they believed functioned much like neurons from a biological organism: the neural network.

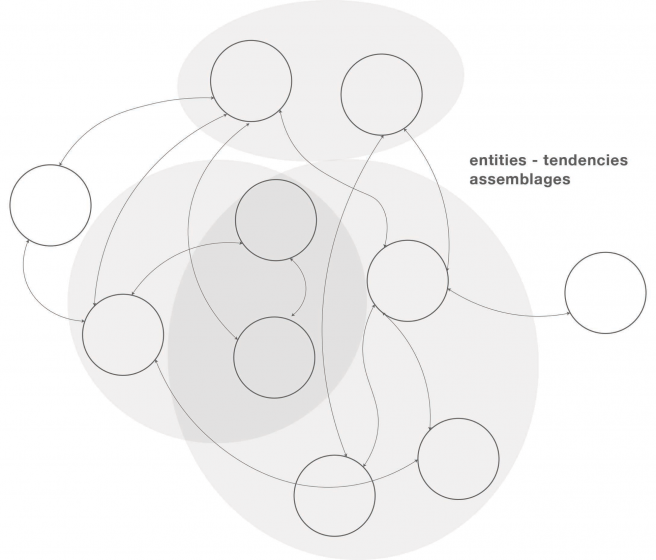

To understand neural networks, it is surprisingly easier to start from linear regression than it is to start from the biology of neurons. Recall that a linear regression model relates multiple input variables to a single output variable through error-minimizing coefficients, which we can picture as inputs (circles) combining to form an output (a circle) through multipliers (lines).

One of the characteristic flaws of linear regressions is their namesake linearity. They only work if the input always affects the output in the same proportion. In the neighborhood apartment example before, if the apartments in our neighborhood are either large and expensive or small and cheap, with no middle ground, a linear regression will not be able to draw any conclusions. What we need instead is a model that can keep track of details. In the complex world, some details matter sometimes but are irrelevant other times. The easy way to model these conditions is to connect many linear regressions using a middle “layer” of activations.

An activation is an intermediate prediction—instead of predicting whether an input corresponds to an apartment in our neighborhood, we predict how strongly this input activates another set of predictions. Only when a particular combination of inputs is “strong” does the middle layer provide its part of the output. Thus, when an apartment is small and cheap, an intermediate neuron activates, if it is large and expensive, a different intermediate neuron activates, and the linear sum of those two neurons tells us whether or not a specific apartment is in our neighborhood.

Neural networks had limited success for decades after their invention, being applied mainly by the postal services to read the handwritten addresses on letters, until scientists began assembling them with very large numbers of activation layers, in so-called “deep learning” models. They could do this because computational power and speed increased dramatically and they now can afford to run exponentially increasing iterations. The result is an explosion of applications in advanced pattern detection, from identifying fraudulent financial transactions, to filtering spam email, to suggesting movies you might enjoy watching right now, or identifying which of your friends appears in a picture someone took at your birthday party.

The success of deep learning on large data sets had two interesting outcomes. First, there is no longer any clean mathematical description of the solution to such a network. The state-of-the-art algorithm to train them is called stochastic gradient descent, which is a fancy way of saying that the coefficients are iterated by a random amount of error correction until they fall into place (or like shaking a box until it stops rattling).

The second outcome is that it becomes practically impossible to understand how the model makes its predictions. We can look at them and be amazed or amused only.

The focus on building up predictions using combinations of small details can produce results that seem to us absurd. For instance, here are many pictures of dogs and muffins that are highly similar. The world’s most complex neural networks struggle to tell them apart.

This shows that an enormous gap remains between machine intelligence and human intelligence. We know so much about context that it is obvious to us when a chihuahua differs from a muffin, but the machine knows only pixels and how they combine into activation patterns.

The interesting fact, however, is how efficient this machine is at combining its ability to identify muffins with its ability to identify dogs. Its first layers activate almost identically for both kinds of pictures because at that level of detail they are nearly the same. This means that the more layers of complexity a neural network is built from, the more it is able to retrain to answer wildly different, or never yet encountered questions, so long as the basic patterns of those questions match patterns that were encountered before.

The kind of system a city is

How does this help us understand cities and problems of organized complexity in general? I am not suggesting that cities are neural networks, but that they both belong to the category of complex adaptive systems, and show similarities in behavior. The non-linearity of neural networks provides a useful illustration of how details can matter in complex systems, but also of the importance of iteration for adaptation. Many problems can share details yet resemble nothing at the large scale, such as the problems of identifying muffins or dogs in pictures. It turns out that a system trained in one area can quickly adapt to the other. It also turns out that we can’t really plan for these outcomes.

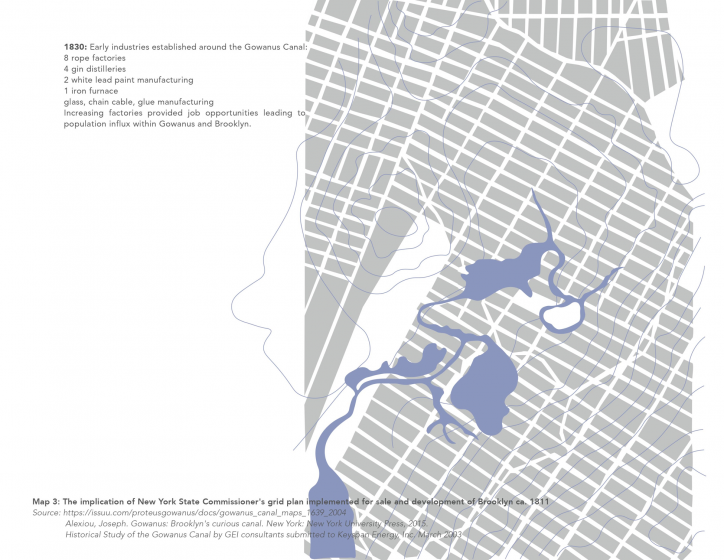

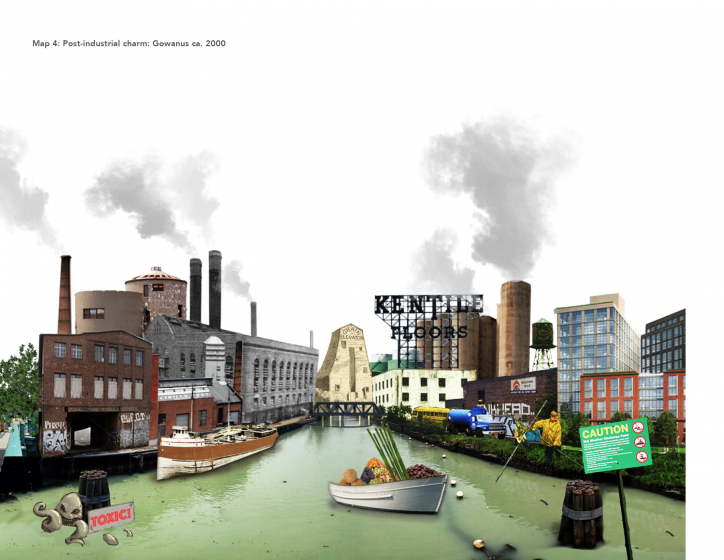

As an example of how this works for cities, the decades following the publication of Death and Life of Great American Cities saw the end of a particular kind of harbor-industrial economy, notably along the harbor of New York. The city was left with warehouse after empty warehouse, an emblem of the decline of cities until some adventurous citizens began repurposing them as workshops and condominiums. The industrial city, while preserving some of its details, completely shed its industrial function and soared back to life as a new form of urban living.

It turns out that the city is not a machine for living or a machine for production, but it is a learning machine, exactly like an artificial neural network learns. A few cycles after the activations for industry stopped, the system found a new path to iterate on while preserving the bulk of its structure.

There is another field where the distinction between linear models and complex models matters greatly: agriculture. Linear agriculture was championed by the United States government in the 20th century for its simplicity and the abundance it produced. All a farmer needed to know was that combining specific land, machinery, fertilizers and pesticides (the inputs) could greatly increase the yield of a crop (the output). The agronomist Norman Borlaug was even given a Nobel prize for inventing a particular combination of inputs that led to wheat being practically free to purchase for the average family. Linear agriculture was driven to its absurd extremes in the Soviet Union, where large state-owned farms could specialise in such narrow crops as beet seeds, under the theory that ever larger and more specialized farms would produce even better yields.

Organic farmers rebelled against this model because they considered it unsustainable, meaning it could not be retrained to adapt to changing conditions. Organic farming’s product is not a commodity crop but the vitality of the soil itself and its ability to produce again, the equivalent of training the middle layers of the neural network or improving the streets of a city to invite buildings of an unspecified type. Organic farmers thus produce what is best to improve the soil, and their main challenge is finding markets for those products, instead of optimizing for existing commodity markets by refining the inputs.

The urgency of thinking of cities in terms of complex or organic models has now moved from industrial cities, which have completely transformed and reinvented themselves and in essence are learning how to learn or become organic, to the suburban sprawl cities that are now finishing their first lifecycle and have never had to endure loss of purpose. Becoming a complex system is learning how to change, and when the next unexpected cycle occurs those cities that have already been through major change start with a strong advantage over those that have always followed the same path.

The current panic over a retail “apocalypse”, the collapse in demand for simple suburban stores while the online retailers whose headquarters are anchored in cities soar in value, shows just how far we have come in the transformation of the industrial city. The end of suburban retail should be seen as both a crisis and an opportunity. What new purpose can be devised for the shuttered buildings and parking lots? They typically occupy the most central areas (in fractal terms) of many automobile-oriented cities and should be apt to fulfill any number of purposes. The one thing standing in the way of their re-adaptation are laws stating that their sole purpose is retail, now and forever. Such laws could be repealed overnight. Can these areas produce learning and iteration instead?

After the retail apocalypse is the office park apocalypse and the housing subdivision apocalypse, as they both reach the end of their initial lifecycle. The lessons learned by the retail zones will be crucial to the adaptation of the other two, and may even prevent an apocalyptic outcome by encouraging local inhabitants to welcome change in their environment. Urban planners increasingly must rely on complexity science to inform the decisions that these communities will make, since those decisions make no sense under any other scientific paradigm.

Mathieu Héile

Montréal

Leveraging the

Leveraging the

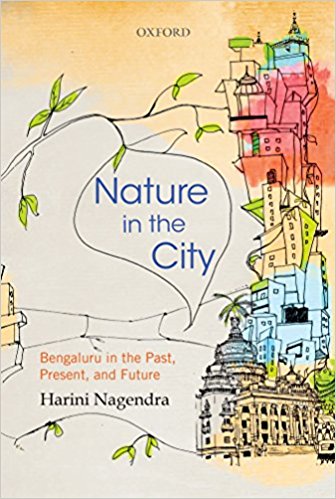

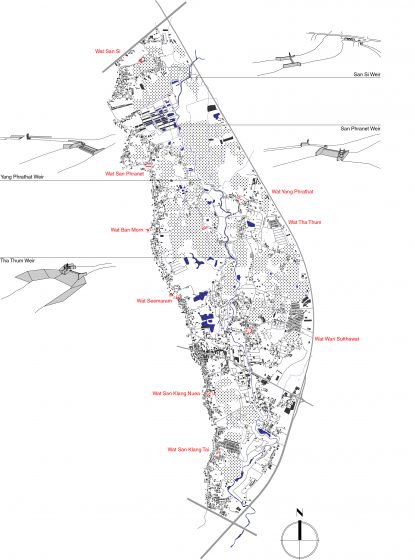

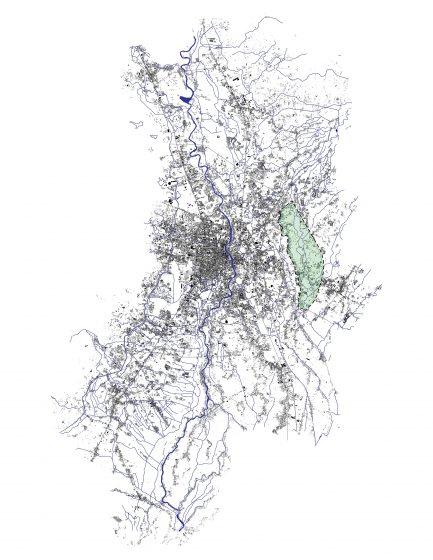

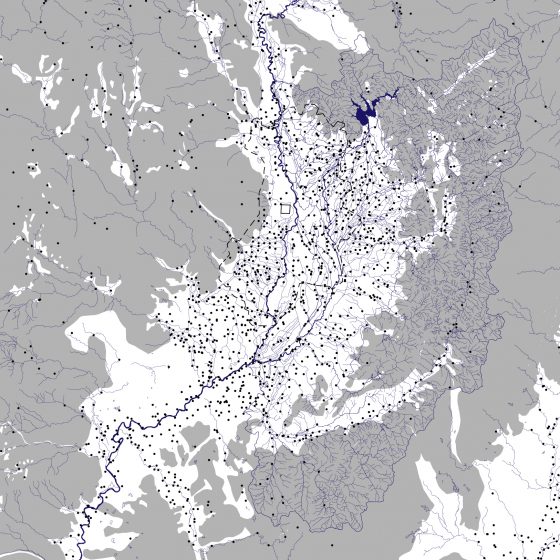

The book tells the story of the emergence of the city, laying out the biophysical and natural history of the original site of Bengaluru, from the early establishment of villages and initial settlement, the growth and development of the complex system of lakes, the subsequent British rule and the import of a particular type of nature and the social division of the city, and ultimately to independence and a contemporary Bengaluru which faces global and local environmental challenges. The book never deviates from its intention to share an understanding of nature in the city as a constant that Nagendra describes as both, “enduring in essence and substance”, yet is also, “… constantly transforming its form and function” (p. 7). Against this backdrop, Nagendra picks up on a broad array of urban ecology topics and presents a series of neatly packaged chapters that read like essays and range in scale and focus from the goings on in private yards to the public spaces of streets and lakes. Urban ecology requires a multi-disciplinary agility and Nagendra is undaunted by the task as she moves easily between landscape considerations around significant shifts in vegetation cover through time, to places of worship, and down to the social anthropology of life under individual trees. She states as her intent to “depict to the reader how nature has played a changing role during the evolution of the South Indian City” (p. 5) and she certainly achieves this.

The book tells the story of the emergence of the city, laying out the biophysical and natural history of the original site of Bengaluru, from the early establishment of villages and initial settlement, the growth and development of the complex system of lakes, the subsequent British rule and the import of a particular type of nature and the social division of the city, and ultimately to independence and a contemporary Bengaluru which faces global and local environmental challenges. The book never deviates from its intention to share an understanding of nature in the city as a constant that Nagendra describes as both, “enduring in essence and substance”, yet is also, “… constantly transforming its form and function” (p. 7). Against this backdrop, Nagendra picks up on a broad array of urban ecology topics and presents a series of neatly packaged chapters that read like essays and range in scale and focus from the goings on in private yards to the public spaces of streets and lakes. Urban ecology requires a multi-disciplinary agility and Nagendra is undaunted by the task as she moves easily between landscape considerations around significant shifts in vegetation cover through time, to places of worship, and down to the social anthropology of life under individual trees. She states as her intent to “depict to the reader how nature has played a changing role during the evolution of the South Indian City” (p. 5) and she certainly achieves this.

1 Comment

Join our conversation