Like a lot of people, my new year’s resolution last year was to stop spending so much time on Facebook and other social media. And like probably a lot of people, I completely failed. So this year, I made a different resolution. This year I resolved to spend more time on social media.

To clarify, I resolved to keep using social media but to make active efforts to post things and be more engaged. I realized I had become a social media lurker, spending hours scrolling through Facebook or Twitter feeds, but hardly ever posting anything myself. My notification areas were empty. Social media and all our modern tech is supposed to connect us, but for all the time spent online, I was making very few actual connections to other people.

Studies from the past few years indicate that this is a trend. Although people are superficially more connected than ever before, many of us still feel more lonely. In fact, there were a number of stories a few years ago about an “epidemic” of loneliness among teenagers in the UK, where the government recently appointed a “minister of loneliness”. So I’m trying to post something I find interesting on Facebook every day, and use its platform as a way to actually communicate with other people.

I am writing about this for TNOC as a way to make my resolution part of the public record, increasing my chances of keeping it, and also because it is relevant to the nature of cities as an analogy for what I see happening related to connectivity in fields like biodiversity conservation, sustainable development, and others that we read about here. I have been writing on TNOC for a few years about biocultural diversity, particularly discussing biocultural connectivity, and these topics seem particularly relevant to what is happening today. In short, some of the very institutions that have been created to enhance connectivity—both interpersonal and environmental—are having exactly the opposite effect.

First, a little background including some recent developments. In Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) processes, we are approaching the end of the timeframe for the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020, which coincides with the UN Decade on Biodiversity. The Aichi Biodiversity Targets are the heart of the Strategic Plan, consisting of 20 targets of varying scope and specificity, supposedly to be achieved during the Decade (although, as we will see below, some of them are conceived as aspirational targets and cannot reasonably be expected to be achieved within one or even several decades). The timeframe for these targets is therefore coming to a head as Parties to the CBD consider what progress has been made, which targets are and are not likely to be met, the process of how the targets were produced, and what lessons can be learned for what comes after 2020. Mention has already been made in CBD negotiations of a “post-2020 global biodiversity framework”, and it is expected that a new set of targets will be adopted at the CBD’s fifteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties (CBD COP 15) in China in 2020.

Within the context of the Aichi Targets, connectivity is most explicitly mentioned in relation to Target 11, which says “By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water areas and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscape and seascape”. This is usually thought of as the target on protected areas, but—in a reflection of the difficult negotiation process that produced the Strategic Plan—a lot of different ideas got tossed into the word salad that is this target, so it could also be about concepts like “equitably managed”, “integrated”, and “well connected”. But generally speaking, connectivity shows up in CBD contexts essentially as a function of protected areas management.

Pitfalls of quantifiable targets

Target 11 is unusual among the Aichi Targets because it is one of the few that includes measurable numbers for parties to aim for, by specifying 17 percent for terrestrial and inland water areas and 10 percent of costal and marine areas to be somehow protected. Other targets are vague about requirements to be met, for example, Target 7: “By 2020, areas under agriculture, aquaculture and forestry are managed sustainably, ensuring conservation of biodiversity”. What is meant by “areas” in this context? All agricultural land, or just some of it? This—similar to Target 1: “By 2020, at the latest, people are aware of the values of biodiversity and the steps they can take to conserve and use it sustainably” among others—is an example of an aspirational target, unlikely to be met within the UN Decade on Biodiversity.

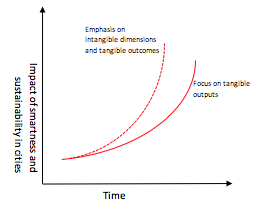

The pitfall here is that because Target 11 includes quantitative goals, countries can positively evaluate their progress in achieving it, by counting hectares of protected areas or kilometers of protected coastlines. But in doing so, uncountable concepts like integration and connectivity get lost. After all, it is a relatively simple matter to count protected areas, but not to quantify whether they are ecologically representative, well-connected and integrated into the wider landscape. This is one reason why a major survey like the Global Biodiversity Outlook 4 indicates that despite protected area coverage growing globally and likely to meet the target, the status of biodiversity continues to decline.

There are, therefore, two lessons that we should hope CBD negotiating parties will take from the experience of Aichi Target 11 as they look toward creating the next set of targets for the post-2020 global biodiversity framework. One is putting too many elements into one target results in a lack of focus and confusion about the actual goal of the target. The other is that targets must be consistent in identifying quantifiable goals or not. Otherwise, parties will find it easier to focus on quantifiable targets, to the detriment of all of the other targets and important concepts like connectivity.

In case you needed another acronym to remember, meet “OECMs”

An ongoing effort to address some of the concepts included in Target 11 is work by IUCN and partners developing “guidelines for recognising and reporting other effective area-based conservation measures” (OECMs). OECMs were included in Target 11 in an attempt to address some of the very problems identified here by making sure that it is not simply a matter of creating official protected areas, but also recognizing that many different types of land-uses can benefit biodiversity, from indigenous-controlled lands to Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS) recognized by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) or “socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes” promoted in the Satoyama Initiative.

Unfortunately, the lessons suggested above seem not to have been learned in developing these guidelines, which define OECMs as distinct, clearly defined areas set aside for biodiversity conservation. In other words, these are protected areas in every way other than legal recognition as such. This approach results in the same problems we see in protected areas, namely that they are so specific and narrowly-defined that they cannot be integrated parts of a “well-connected system” as prescribed in the target. This represents a real missed opportunity since the idea of OECMs is well-suited to embrace connectivity and integration into the landscape if areas like buffer zones and biocultural corridors were included. The guidelines as they currently exist are more likely to only apply to a small number of isolated pockets of biodiversity, and provide no motivation for integration or connectivity. It can only be hoped that these issues will be dealt with somehow in future planning.

At the beginning of this essay, I described how communications technology available to each individual person in modern society has gotten much greater, but a lack of real connection between these individuals shows that this technology is not achieving its intended purpose due to a lack of real, robust connectivity. I hope the analogy has become clear to the continuing tendency towards creating protected areas, and now OECMs, as isolated pockets that each may contain great biodiversity but are not achieving the intended goal of improvements to the biodiversity situation. In both cases, it is a lack of connectivity that prevents these instruments from fulfilling their purpose.

Slow progress on biocultural connectivity

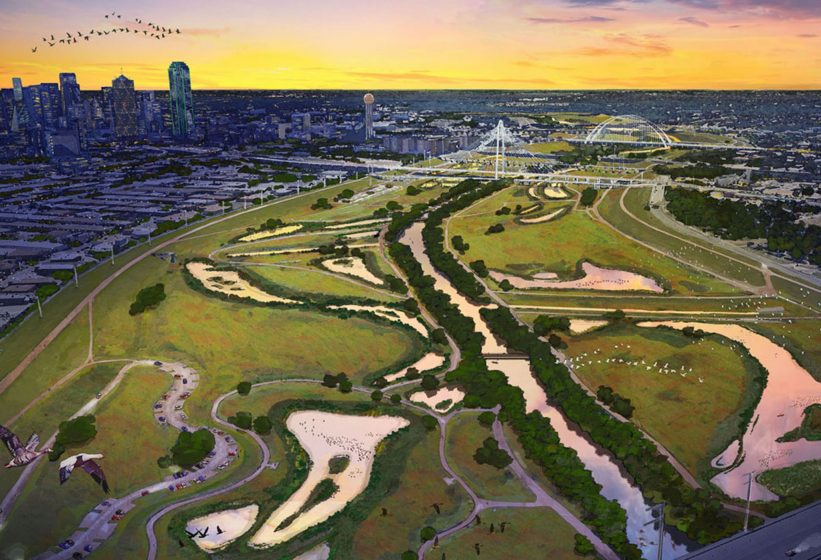

For Target 11 to be fully effective, protected areas need to be integrated into landscapes where much more land area is used for human production activities. I would like to stress that the connectivity needed in wider-scale landscape planning is exactly what we call biocultural connectivity, and this can only be achieved with biocultural diversity. Toward this effort, there are some recent developments in the field of biocultural diversity that I wrote about in an earlier essay, following up on the process of creating an “Ishikawa-Kanazawa model” for biocultural diversity in cities, partly led by the government of Kanazawa, Japan.

In 2016, Kanazawa went on to hold the 1st Asian Conference on Biocultural Diversity, where the “2016 Ishikawa Declaration on Biocultural Diversity” was adopted, inviting party governments to support work towards biocultural diversity on a wider scale. The CBD Secretariat and UNESCO’s Joint Programme on Links between Biological and Cultural Diversity and its partners are working to organize “Dialogues for Collaborative Action on the Links Between Biological and Cultural Diversity”, including a number of “action groups” that will discuss various aspects of biocultural diversity to present at CBD COP 14 and 15. The first of these action groups will be “The Action Group on Knowledge Systems and Indicators of Wellbeing”, meeting in April in New York.

My own project’s “Indicators of Resilience in Socio-ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes” are expected to be among materials on indicators presented for the action group’s “cross-cutting exploration of knowledge systems and indicators of wellbeing”. The set of indicators developed in this project attempts to identify elements that suggest whether a landscape or seascape and its resident communities are resilient. It is clear that many of these indicators are biocultural elements, such as “households and/or community groups maintain a diversity of local crop varieties and animal breeds” and “local knowledge and cultural traditions related to biodiversity are transmitted from elders and parents to young people in the community”. This is to say that, to some degree, what makes a landscape resilient is what makes it biocultural.

There is another way the analogy of modern technology failing to connect us as humans and the lack of connectivity in the landscape works. Just as it is relatively quick and easy to create protected areas—still often difficult, but easier than fostering true biocultural connectivity—in order to fulfill quantitative biodiversity goals like Aichi Target 11, sending messages through modern technology is also easy and fast as the speed of light. But again, just as building real connections with people apparently cannot be achieved quickly using technological shortcuts but rather requires time and effort over the long term, building the landscape elements that create biocultural connectivity is also a slow process.

Socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes in places around the world have been created through a slow process of people interacting with nature over hundreds or thousands of years. Rebuilding them where they have become degraded will likewise take years of work and smart management to restore their biocultural connectivity. In much the same way, the often-frustrating negotiations in international processes like the CBD, and the process of arriving at a truly effective global biodiversity framework, can be slow and not immediately gratifying. Perhaps we should not be overly afraid of slow progress, and trust that the very process of undergoing these negotiations is itself a kind of connectivity-building, just as continuously working the land can result in harmonious connections between humans and nature.

Going back to my analogy for how this biocultural connectivity relates to interpersonal connectivity via social media, so far, my new year’s resolution to post daily on Facebook has not resulted in any immediately satisfying improvement in connectivity, although I have mostly stuck to it. But in a small way, I am already having a few more interactions with friends on the site every day, finding common interests, or just joking about a silly picture. These little interactions provide a few more things that my friends and I have in common, gradually forming a little more solid basis to our relationships. Turning social media technology into something worthwhile is a slow process of making connections, and making connections is itself what builds connectivity. Similarly, producing the post-2020 global biodiversity framework will be done in a flurry of policymaking and negotiations over the next few years, but achieving the real goals of a world where people live in harmony with nature is going to be long-term and slow, and only achieved by doing the hard work to build many different forms of connectivity.

William Dunbar

Tokyo

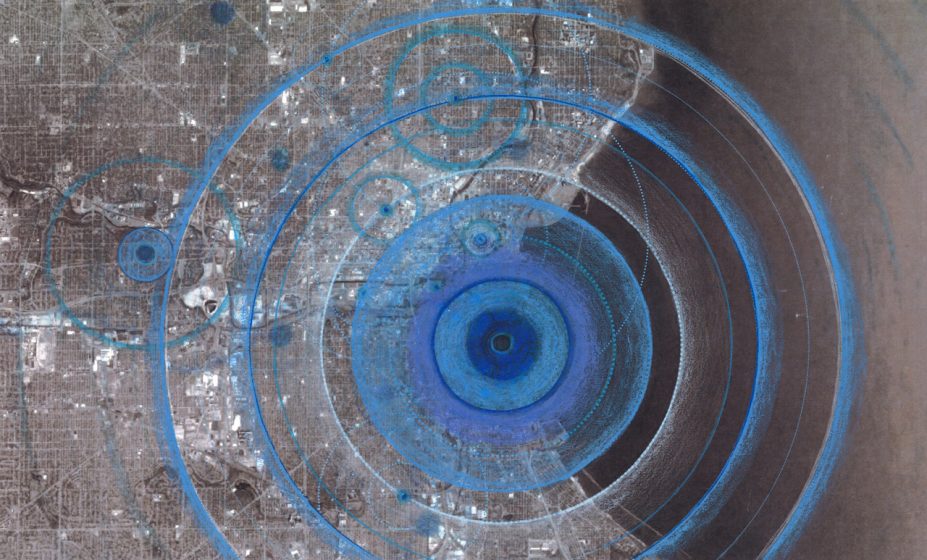

But if our goal is for better cities—cities that are better for both people and nature—what can smart cities do for us? How can the technology of smart cities be specifically directed toward the creation of ecologically sophisticated cities that serve human well-being? Can the benefits they provide be distributed justly and equitably, for everyone and not just a few? Can the services they provide be about more than just technology?

But if our goal is for better cities—cities that are better for both people and nature—what can smart cities do for us? How can the technology of smart cities be specifically directed toward the creation of ecologically sophisticated cities that serve human well-being? Can the benefits they provide be distributed justly and equitably, for everyone and not just a few? Can the services they provide be about more than just technology?

The book begins with a chilling snap shot of present urban life in Kuwait: four fatal criminal incidents (2012 – 2013) which shocked the general public because they were undertaken in the open, “in the midst of hundreds of witnesses who chose not to intervene” (p. 2). Al-Nakib argues in the remainder of the book that the transformation of urban areas in Kuwait has led to a “highly segregated and factional society” where such incidents are to be expected. In this piece, I hope to draw out the book’s main themes and arguments which are applicable not only to Kuwait but also to the wider region, and perhaps also to other fast-developing cities around the world.

The book begins with a chilling snap shot of present urban life in Kuwait: four fatal criminal incidents (2012 – 2013) which shocked the general public because they were undertaken in the open, “in the midst of hundreds of witnesses who chose not to intervene” (p. 2). Al-Nakib argues in the remainder of the book that the transformation of urban areas in Kuwait has led to a “highly segregated and factional society” where such incidents are to be expected. In this piece, I hope to draw out the book’s main themes and arguments which are applicable not only to Kuwait but also to the wider region, and perhaps also to other fast-developing cities around the world.

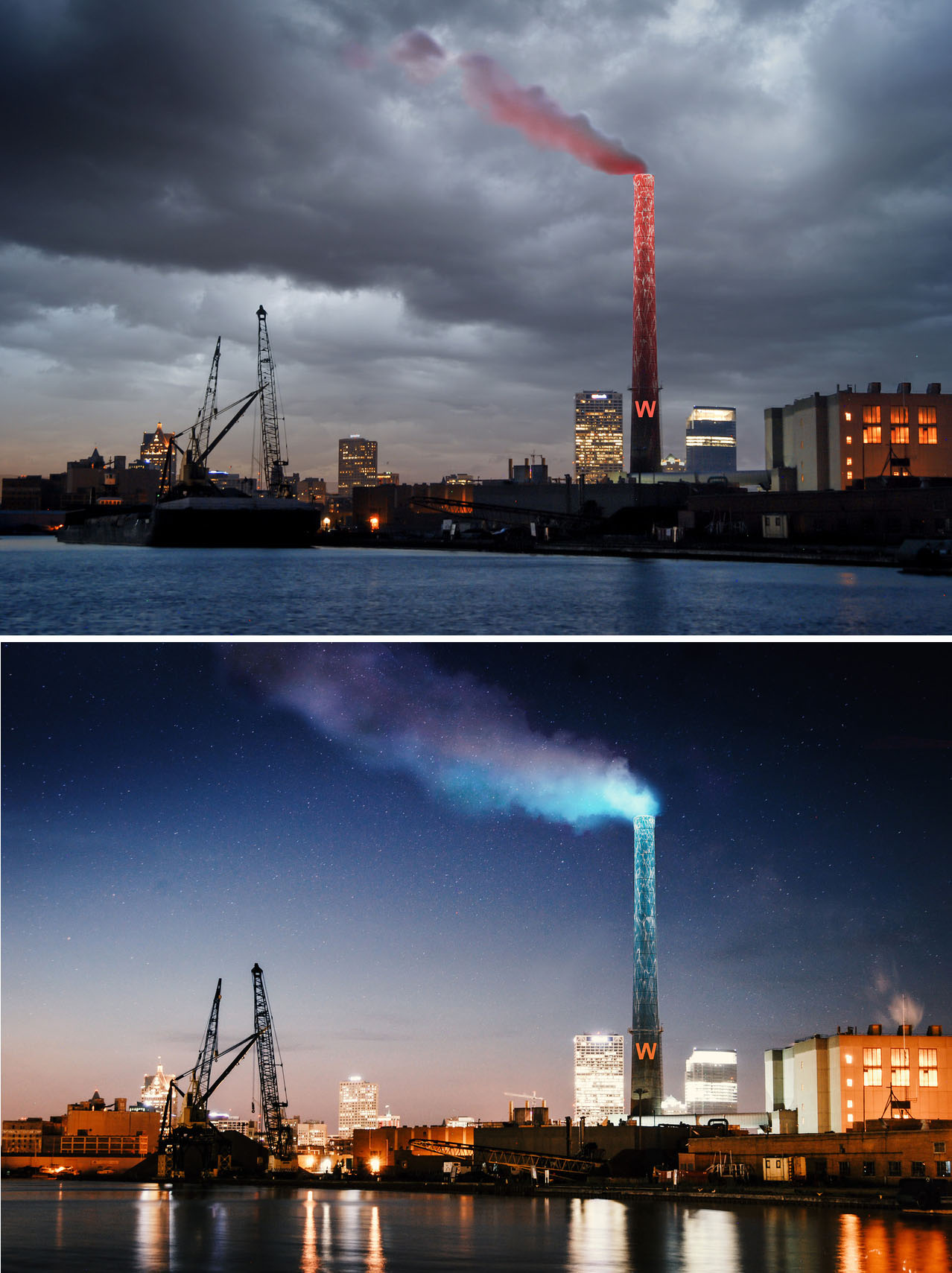

Along similar lines, we find today that architecture has become something that needs to be “marketable”—packaged, marketed, and then sold to consumers—thereby distancing itself from the very processes that we have always associated architecture with. These processes require designers to ideate through multiple scenarios that take into account social, ethical, and even political factors surrounding a project, and promote the want to effect change in the local environment and contribute to it positively. It is quite disheartening when the need to sell a project by means of an image gives rise to projects that are beautiful and exhilarating visually but are hollow and many times soulless in terms of their impact on their surrounding environment—both natural as well as built.

Along similar lines, we find today that architecture has become something that needs to be “marketable”—packaged, marketed, and then sold to consumers—thereby distancing itself from the very processes that we have always associated architecture with. These processes require designers to ideate through multiple scenarios that take into account social, ethical, and even political factors surrounding a project, and promote the want to effect change in the local environment and contribute to it positively. It is quite disheartening when the need to sell a project by means of an image gives rise to projects that are beautiful and exhilarating visually but are hollow and many times soulless in terms of their impact on their surrounding environment—both natural as well as built.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation