Regularly, we feature a Global Roundtable in which a group of people respond to a specific question in The Nature of Cities.

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David's dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to "fall back on". So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

In 2016 we assembled a list of 90 must-reads on cities suggested by a diverse group of TNOC contributors—a nature of cities reader’s digest.

This year we asked 90 TNOC contributors for a single must-read book on urbanism from a specific continent. From a diverse set of TNOC contributors, we asked: from your world, discipline, or point of view, if a person were interested in urbanism on a particualr continent, what should they read? The book has to be really about that continent, not a general book about urbanism that happens to apply to the continent. For example, Death and Life of Great American Cities certainly is relevant all over, but it isn’t specifically about Asian cities. The people recommending these books are either from the contents they are recommending for, or work there extensively.

The recommendations are as wide-ranging as the TNOC community, from many points of view, and from around the world. They are a reflection of the breadth of thought that cities need, and they speak to the specific and sometimes unique needs of different parts of the world.

What we have created here is a remarkable and diverse reading list. You will likely think of other essential works yourself, and when you do, leave them here as a comment. There is a rich conversation to experience simply by exchanging ideas on great books.

The list below could serve as a wonderful primer for courses or other gatherings. You can download the entire list as a PDF here.

You can download the last year’s global list as a PDF here.

Check out these titles at your local, corner bookstore. But if you choose to buy one of these titles online, please click here to go to Amazon . Some of the sales price will benefit TNOC.

. Some of the sales price will benefit TNOC.

Get busy.

—David Maddox

AFRICA

Gina Avlonitis, Cape Town

Gina Avlonitis, Cape Town

Growing Together: Thinking & Practice of Urban Nature Conservators

by Bridget Pitt & Therese Boulle

2016

This is a beautifully presented book that gives sincere, first-hand, and humanity-filled insights into the successes and failures of community-development-oriented urban nature conservation in Cape Town. Although it isn’t a theoretical book, it does delve into some of the theory of collaborative management while striking a good balance with offerings of practical experience and solutions on a range of topics: from mapping socio-ecological systems to issues of leadership; from collaborative learning to growing community and passion; from ‘putting food on the table’ to issues of buy-in and access. The case studies and experiences may be Cape Town based, but the book is definitely relevant and a valuable resource for anyone wishing to engage in community driven nature conservation in other contexts.

Buy the book.

Pippin Anderson, Cape Town

Pippin Anderson, Cape Town

Fynbos: Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation of a Megadiverse Region

Edited by N. Allsopp, J. Colville, and G.A. Verbose

2014

I was raised academically as a botanist and as a result my go-to text at the start of any project will always be “Fynbos: Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation of a Megadiverse Region”. This is a second edition and follows nicely on from the first, and to my delight the new edition has a chapter that directly engages with the role of people and even urban form in the Fynbos biome, titled, People, The Cape Floristic Region, and Sustainability. I think as an urban ecologist my starting point is always the original biophysical template and this book is state of the art with respect to explaining the original vegetation type of the region, the underlying soils and the other factors determining the physical environment.

Buy the book.

Kobie Brand, Thea Buckle, Jessica Kavonic, Michelle Preen & Meggan Spires, Cape Town

Kobie Brand, Thea Buckle, Jessica Kavonic, Michelle Preen & Meggan Spires, Cape Town

The State of African Cities 2014: Re-imagining sustainable urban transitions

2014

This report takes an in-depth look at the opportunities and challenges experienced in African cities, and argues for a bold re-imagining of prevailing models in order to steer ongoing transitions towards greater sustainability based on a thorough review of all available options. The report interrogates what innovative responses are possible in response to the already daunting urban challenges faced in Africa, which are being exacerbated by vulnerabilities and threats associated with climate and environmental change.

Buy the book.

Katrine Claassens, Montreal

Katrine Claassens, Montreal

Welcome to Our Hillbrow: A Novel of Postapartheid South Africa

by Phaswane Mpe

2011

Welcome to our Hillbrow provides a poignant description of life in post-apartheid Hillbrow, a neighbourhood in central Johannesburg. We follow the life of Refentše Morrow, a student living in the dirty and unforgiving but yet always alluring city. The novel could have easily been a pastoral lament, filled as it is with references to Refentše’s rural roots in the village of Tiragalong, but the countryside remains a place of unease offering no real respite from Hillbrow’s gritty realities.

Buy the book.

Nadja Kabisch, Berlin

Nadja Kabisch, Berlin

Urban Vulnerability and Climate Change in Africa: A Multidisciplinary Approach

by Pauleit, St., Coly, A., Fohlmeister, S., Gasparini, P., Jorgensen, G., Kabisch, S., Kombe, W., Lindley, S., Simonis, I., Kumelachew, Y. (Eds.)

2015

This book is a must read because, to my knowledge, it is one of the first that presents very concrete methodological approaches and in-depth strategies on the assessment and on how to deal with climate change and urbanisation induced challenges in an African urban context. This context is in so many dimensions different from the context we know from the western developed world. The most interesting is, that related challenges are addressed in case studies such as Dhar es Salam, Tansanina, with multi-method approaches, including modelling, GIS techniques but also household questionnaires and qualitative interviews to address not only the challenges for a sustainable urban land development but also social vulnerability.

Buy the book.

Shuaib Lwasa, Kampala

Shuaib Lwasa, Kampala

Urbanisation, Urbanism and Urbanity in an African City: Home spaces and House Cultures

by Paul Jenkins

2013

This book is a great piece that highlights the everyday experiences of homemaking and space configuration in peri-urban areas inMaputo. Although it focus on Maputo, the text resonates with many African Cities particularly Sub-Saharan Africa. The book raises the notion of building the city from below and the importance of socio-cultural agency that starts from a non normative perspective about African cities. The book underscores how homemaking is shaped by the social systems and a non-structured system of urban governance in which ideal principles exist but often pushed back by the social cultural uniqueness of the place.

Buy the book.

Susan Parnell, Cape Town

Susan Parnell, Cape Town

How to Steal a City: The Battle for Nelson Mandela Bay: An Inside Account

by Crispian Oliver

2017

On the imperative of protecting strong and robust local states that can withstand the corrosion of corruption that undermine the public good and the benefit of carefully constructed municipal capacity designed to protect people and planet under conditions of rapid urbanisation.

Buy the book.

Elisabeth Peyroux, Paris

Elisabeth Peyroux, Paris

New Urban Worlds: Inhabiting Dissonant Times

by AbdouMaliq Simone, Edgar Pieterse

2017

It is a very imaginative, thought-provoking book about how to engage with the “make-shift” character of African (and Asian) cities both within and beyond the boundaries of our knowledge. It connects the practices of everyday life and behavior to current forms of “governing the urban”, acknowledging the need to re-describe the cities along a a multiplicity of story lines. It shows how African (and Asian) urban residents address many possible futures at once.

Buy the book.

Debra Roberts, Durban

Debra Roberts, Durban

Zoo City

by Lauren Beukes

2010

It is a science fiction novel that crafts an alternative a view of one of Africa’s most complex and significant cities. It speaks to exclusion and dispossession in defining the quality of urban lives and the strong links between the human and natural spirit in defining the essence of an African city.

Buy the book.

David Simon, Gothenburg

David Simon, Gothenburg

Climate Change at the City Scale; Impacts, mitigation and adaptation in Cape Town

edited by Anton Cartwright, Susan Parnell, Gregg Oelofse and Sarah Ward

2012

The ever-sharper focus of climate/environmental change impacts and coping strategies in urban areas is still heavily skewed towards wealthy countries and cities as a reflection of available resources, skills and relative prioritisation. Although the balance is shifting, urban Africa remains under studied, particularly since the continent is predicted by the IPCC to be particularly vulnerable to some of the most severe changes by 2100. This book represents a landmark as the first substantive analysis of the current and predicted future impacts, along with how mitigation and adaptation efforts are unfolding, at the scale of a major African metropolis.

Buy the book.

ASIA

Xuemei Bai, Canberra

Xuemei Bai, Canberra

王如松:《高效、和谐–城市调控原理与方法》, 湖南教育出版社, 1988, 278页.

Efficiency and Harmony: Principles and methods of urban system regulation and control

by Rusong Wang

1988

Rusong Wang is an internationally renowned urban system ecologist, whose work laid the foundation of urban ecology research in China, and influenced and contributed greatly to the theory and practice of eco-city development in China. Although not always highly cited in the English literature, some of the concepts and thoughts presented in this book—e.g., cities as complex social-economic-ecological systems—were inspirational in the 1980s and are cutting edge even today. Nominating this book is also a way to pay tribute to a fine urban scholar and his achievement—he passed away in 2014 at the age of 67.

Timothy Bonebrake, Hong Kong

Timothy Bonebrake, Hong Kong

The Ecology of a City and its People: The Case of Hong Kong

by S. Boyden, S. Millar, K. Newcombe, and B. O’Neill

1981

This is a classic book in urban ecology that examines the city from an ecosystem perspective, with humans as a key and integral component of the ecosystem. In the 35 years since the book was published, Hong Kong has changed dramatically in many ways, including a 40 percent increase in population size and skyrocketing rates of consumption—this book provides a fascinating source of perspective in light of these changes. While some of the specific conclusions may well be unique to Hong Kong, the general patterns are largely applicable to growing cities worldwide.

Buy the book.

Bharat Dahiya, Bangkok

Bharat Dahiya, Bangkok

The State of Asian Cities 2010/11

The State of Asian Cities 2010/11 features a comprehensive review of the trends in inclusive and sustainable urban development in the Asia-Pacific region. Being the first-ever report on the state of Asian-Pacific cities prepared by the United Nations, it brings together rich analysis of and policy review on urban demographic, economic, poverty, environmental and governance issues. As Prof. Andrew Kirby, former Editor of Cities journal and its current City Profiles Editor wrote, “[t]he report represents a benchmark against which we could all measure our urban research”.

Download the book.

P.K. Das, Mumbai

P.K. Das, Mumbai

Anil Agarwal Reader, Three Volumes

Content editor: Pratap Pandey

Series editor- Sunita Narain.

2007

A must. In 1982 Anil was the founder Director of Centre for Science and Environment (CSE). Although he died in 2002, he established an Institution that continues to drive the environmental message, as loudly and stridently as he would have done.

Buy the book.

Haripriya Gundimeda, Mumbai

Haripriya Gundimeda, Mumbai

A place in the Shade: The New Landscape and other Essays

by Charles Correa

2012

The book offers a wonderful collection of essays on concerns and issues that are fundamental to india and covers several dimensions like 1) description of the architecture and the cities and the disconnect with people who use them 2) the role of cities in modernizing India: 3) architecture and urbanization in India ; 4) what cities are about and the role of culture. The book also offers some solutions to the modern problems.

Buy the book.

Fadi Hamdan, Beirut

Fadi Hamdan, Beirut

Urban Development in the Muslim World

Edited by Hooshang Amirahmadi and Salah El-Shakhs

1993

A very interesting perspective on the evolvement of some of the historic cities in the Middle and Near East, including Mecca, Delhi, Tehran, Sanaa and various cities in Syria. The chapters identify various socio-economic and political factors that affected urban development including the spread of Islam, the age of air travel, colonisation and other interesting urban development drivers. The book also refers to some important North African Cities including Cairo and other Maghreb Cities in Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco and how these are influenced by, and affected, other urban developments in the Middle East.

Buy the book.

Keitaro Ito, Kyushu

Keitaro Ito, Kyushu

The City of the Unseen

by Fumihiko Maki

A book about the structure of Tokyo: its history and topography, and analysis from architectural point of view. It is very interesting and worth reading, especially the discussion about the philosophy of “the depth” in the structure of the city.

Alpana Jain, Delhi

Alpana Jain, Delhi

Celebrating Public Spaces of India

by Archana Gupta and Anshuman Gupta

2017

Through examples it gives a very good overview of the importance of public spaces in the Indian cultural context and how they are being trivialised by insensitive urban growth.

Buy the book.

Maggie Lin, Hong Kong

Maggie Lin, Hong Kong

Community Design: Reimagining “community”, beyond space, but human connections

by Yamazaki Ryo

It shares bottom-up urbanism initiatives, from parks design to department store revitalization, to bring the community together and weave the social fabric. A very human-centred approach: 社區設計:重新思考「社區」定義,不只設計空間,更要設計「人與人之間的連結」

Patrick Lydon, Osaka

Patrick Lydon, Osaka

Just Enough: Lessons in Living Green from Traditional Japan

by Azby Brown

2010

Some 400 years ago, Japan was experiencing severe environmental degradation, and the country responded by keeping their borders closed to trade, and learning how to live, build, and think within the ecological means of the land. For two centuries Japan fed, housed, and clothed a population of over 30 million people while simultaneously creating thriving metropolises, market towns, and highly developed arts, crafts, and cuisine. This beautifully illustrated book gives us a peek into the Japanese life and city building during the Edo Period, and helps us imagine how we might again build cities that regenerate the health of the environment instead of degrading it.

Buy the book.

Anjali Mahendra, Delhi

Anjali Mahendra, Delhi

Urbanisation in India: Challenges, Opportunities, and the Way Forward

by Isher Judge Ahluwalia, Ravi Kanbur and P.K. Mohanty

2014

I like it because the chapters offer useful insights and evidence, while covering a rich range of topics related to urbanization in India. The authors comprise a mix of policy makers, researchers and urban practitioners who have worked on these issues for a long time in the country. Finally, based on conversations with colleagues in Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, I think many challenges of urbanization in India are common across the sub-continent, where the majority of cities are facing rapid, under-resourced, under-serviced, unmanaged urban growth. Many of the lessons offered in each chapter are thus widely applicable throughout South Asia.

Buy the book.

Mahim Maher, Karachi

Mahim Maher, Karachi

Karachi: Ordered Disorder and the Struggle for the City

Laurent Gayer

2014

We were lucky, oh so lucky, to have Laurent Gayer explode onto the scene in 2014. Laurent works at Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in France, but came to Karachi for several years to do this book, after having learnt Urdu in India. I believe his ability to conduct his interviews in Urdu, often shocking his unsuspecting subject, was the secret to the success of this granular examination of the forces that shape Karachi. Karachi has a rep for being the most violent city in the world (never mind that Oakland and Ciudad Juarez also once had a higher homicide rate). The violence was inexplicable; sure, experts had their theories, but none of them satisfied me. (I was working as the head of the metropolitan pages during some of its most violent years). What Laurent has done is explain “us”. His brilliant theory is “ordered disorder” or managed chaos. He explains why Karachi continues to function while falling apart every day. Best of all, it is a riveting read because he approaches it almost like a journalist and tells the story. Ordered Disorder is essential reading also for anyone who wants to understand the history of modern Karachi, how certain factors have influenced its growth, decay, and resilience, and how we often work “through” violence.

Buy the book.

Jala Mahkzoumi, Beirut

Jala Mahkzoumi, Beirut

Al Muqaddimah

By Ibn Khaldoun

1377

The book, an introduction to societies of what today comprises the ArabWorld, is outstanding because of the holistic, dynamic methodology devised by Ibn Khaldun that incorporates the multiple layers of cities, religious, political, demographic and ecological, gauging their collective impact on the evolution of the human and physical geographies of these lands and (b) because of his emphasis on ‘asabiyyah’, equivalent to modern day ‘nationalism’, as underlying the political failure of successive cultures of the time. His method and analysis is as valid today as it was seven hundred years ago in deciphering political failures and social injustice that plagues the Arab World. http://www.kitabfijarida.com/pdf/91.pdf

Buy the book.

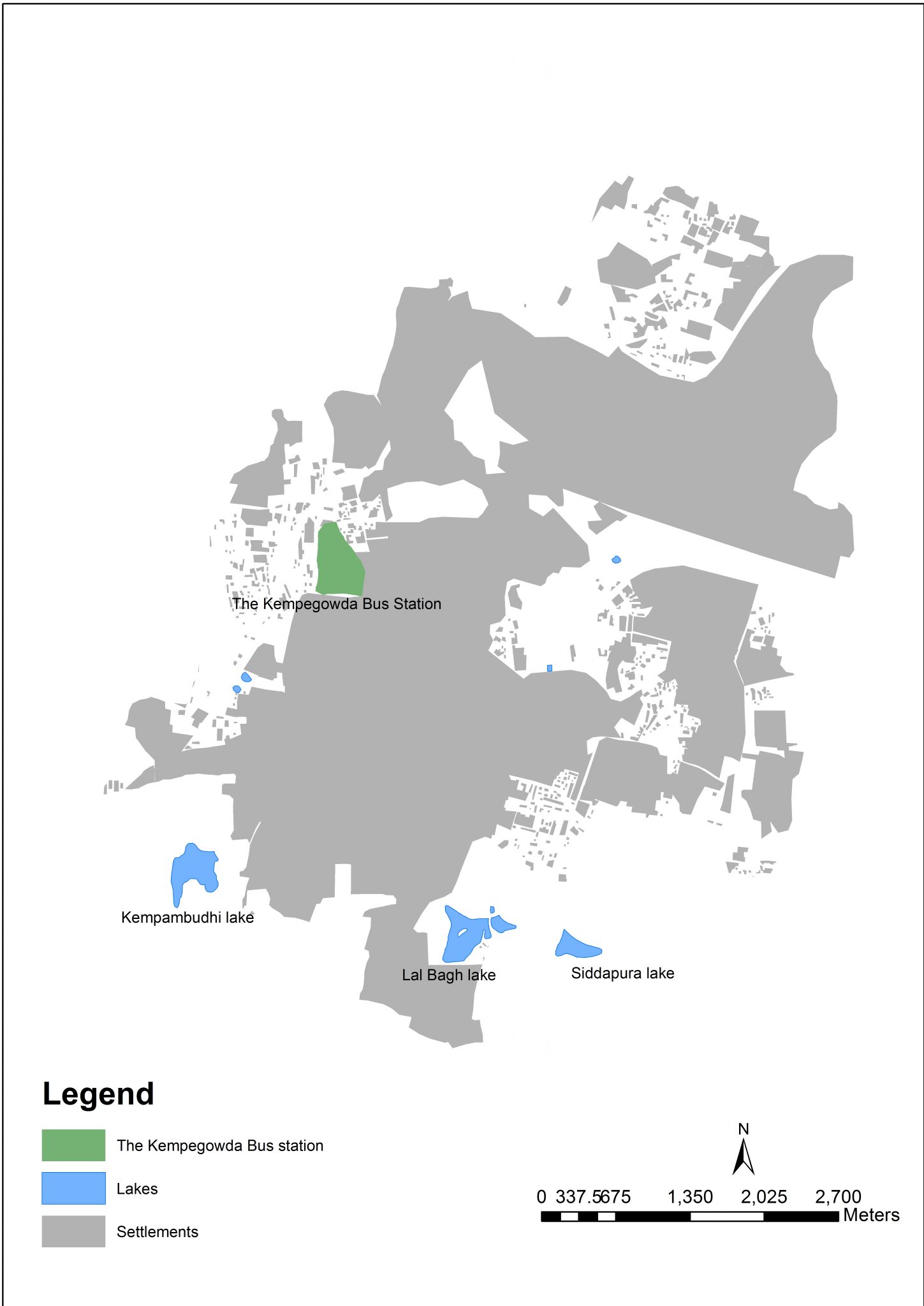

Harini Nagendra, Bangalore

Harini Nagendra, Bangalore

Finding Forgotten Cities: How The Indus Civilization Was Discovered

by Nayanjot Lahiri

2013

The book tells the fascinating story of the discovery of the Indus valley civilization, including the excavation of the ancient city of Harappa, which boasts of the world’s oldest urban sanitation system. Reading the book, you not only recognize the fundamental importance of archaeology and archival work to understanding cities, but also get deep insights into the mechanisms that shaped the structure and function of ancient cities in the Indian sub-continent.

Buy the book.

Daniel Phillips, Bangalore

Daniel Phillips, Bangalore

Nature in the City: Bengaluru in the Past, Present, and Future

by Harini Nagendra

2016

A beautifully written and accessible compendium of research conducted in “The Garden City” over many years. Beyond just Bangalore, Nagendra sheds light on the social-ecological complexities that exist broadly across many contemporary Indian cities as they attempt to balance the forces of development with their historical legacies and natural systems. In contrast to the narratives of loss, doom and gloom that are typically associated with accounts of booming megacities in the global south, this book has a refreshingly optimistic tone, revealing the subliminal forces and relationships that are keeping the notion of Nature alive in the city despite all odds.

Buy the book.

Mohan Rao, Bangalore

Mohan Rao, Bangalore

The New Landscape

by Charles Correa

1985

First published in 1985, this seminal work unpacks the nature of urbanisation beyond the physical. When I read this as a student, it really was like an epiphany! Mr. Correa brings his enormous scholarship to examine the myriad layers of our cities in a clear and succinct manner. Though the book is rooted in the Indian context, even after 32 years, the book remains relevant to every urban practitioner of the global south. The New Landscape avoids jargon and reaches out even to a lay reader bringing together challenges of shelter, mobility, livelihood, informal economy, market forces, governance, and so on. I continue to refer to this classic and would recommend it highly to anyone interested in urbanism.

Buy the book.

Karen Seto, New Haven

Karen Seto, New Haven

Nihon No Toshi

by Pradyumna Prasad Karan and Kristin Eileen Stapleton

1997

A book about the structure of Tokyo: its history and topography, and analysis from architectural point of view. It is very interesting and worth reading, especially the discussion about the philosophy of “the depth” in the structure of the city.

Buy the book.

Huda Shaka, Dubai

Huda Shaka, Dubai

Planning Middle Eastern Cities

Edited by Yasser Elsheshtawy

2004

The book is one of the first to critically consider the modern history of Arab cities, with chapters written by local practitioners and academics. It does each of the chosen cities justice by focusing on their unique history and context and by considering multiple (social, economic, environmental, architectural…) dimensions of its development. The editor also provides a useful lens by which to view the cities and societies in the region and their struggle with modernity.

Buy the book.

Keijiro Suzuki, Yamaguchi

Keijiro Suzuki, Yamaguchi

神山プロジェクトという可能性(〜地方創生、循環の未来について〜)、NPO法人グリーンバレー(日本語)

Possibility of Kamiyama Project (~Regional Revitalization, for the future of sustainability~), by NPO GREEN VALLEY (Only in Japanese)

As an artist, I was looking for an ideal environment that sustains artistic activities with least interference by capitalist society. I came across an artist in residence program in “Kamiyama”, Tokushima Prefecture, Japan and I was totally impressed by their community revitalization program by creative individuals. They locate in a rural area but they take advantages of the internet in order to locally live closely with nature and to keep up with the global community.

Buy the book.

Pengfei XIE, Beijing

Pengfei XIE, Beijing

《社區設計》

by 山崎亮

History of Chinese Urban Planning

《中国城市规划史》

by Prof. Wang Dehua(汪德华)

Published in Chinese in 2005 by the Southeast University Press(东南大学出版社)Translated into English: Community Design by Yamazaki Ryo

The book gives a holistic picture of the development of Chinese city planning from the Pre-Qin Period (21th Century B.C.-221 B.C.) to the modern times, with theories and practices of ancient Chinese city planning that had impacted the Asian World, and its evolvement with the influence of modern planning approaches. It helps us to review the original intention of city planning, and to better understand the culture of a city harmonizing man and nature.

AUSTRALIA and NEW ZEALAND

Steve Brown, Sydney

Steve Brown, Sydney

Stories from the Sandstone: Quarantine Inscriptions from Australia’s Immigrant Past

Peter Hobbins, Ursula K Frederick and Anne Clarke

2016

This newly published book is an archaeological-historical investigation of rock inscriptions at Sydney’s former Quarantine Station (1835 – 1979). It charts stories of new arrivals to Australia and the diseases that saw them held at this place for days, weeks, and months. I recommend it for its multiple narratives of the growth of Sydney as an urban, ethnically diverse, and spectacular city from immigration and medical perspectives.

Buy the book.

Meredith Dobbie, Victoria

Meredith Dobbie, Victoria

The Future Eaters: An Ecological History of the Australasian Lands and People

Tim Flannery

2002

If you are interested in the landscapes upon which Australian cities have been created, read The Future Eaters, by Tim Flannery (Grove Press, 2002). Flannery, a renowned Australian environmentalist and zoologist, writes with flair and fascination about the geography of Australia and various processes of change in the landscape wrought by a succession of human settlers, starting with the Aboriginal people more than 40,000 years ago. The book is an oldie now but remains a goodie.

Buy the book.

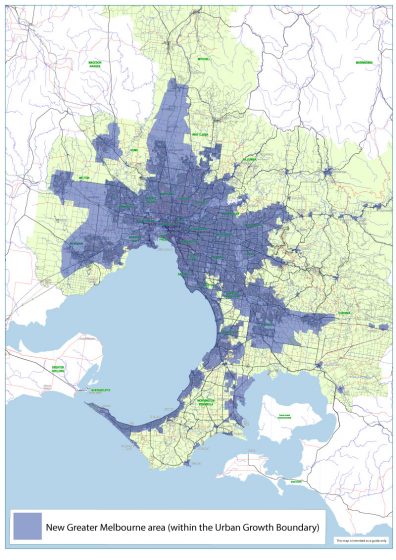

Paul Downton, Melbourne

Paul Downton, Melbourne

Green Urbanism Down Under: Learning from Sustainable Communities in Australia

by Timothy Beatley and Peter Newman

2008

There aren’t many books that deal specifically with Australian urbanism, perhaps because, in this historical bastion of suburbia, the whole idea is a fairly recent discovery. The really worthwhile stuff that’s happening in Australia is in the realm of green urbanism and this 2008 book provides a neat and worthwhile exploration of projects that not only have intrinsic merit but are also selected for their relevance to that other example of a sprawling, gas-guzzling civilisation gone wrong, the USA. Its value isn’t limited to American readers though, not least because the dystopian dreamscapes of fossil-fueled, nature-killing urban form that blight the US have been exported worldwide as models of development, so this is a book that can inform our whole planet of cities with practical examples of how to counter the killing machines of conventional urbanism – although the authors, an American and an Australian, are both much too nice to put it in those terms.

Buy the book.

Amy Kristin Hahs, Ballarat

Amy Kristin Hahs, Ballarat

Landprints: Reflections on Place and Landscape

by George Seddon

1997

This book is a joy to read. Published 20 years ago, but bearing keen insights that remain just as timely and relevant today. Landprints is as much a celebration of Seddon’s passion for the diversity of Australian landscapes, as it is a critique on the relationships between landscapes, human experiences and how these shape our understanding of place. Essential reading for anyone who wants to examine more deeply the connections between people and the land.

Buy the book.

Peter Newman, Perth

Peter Newman, Perth

Planning Boomtown and Beyond

Edited by Sharon Biermann, Doina Olaru and Valeria Paul

2016.

Perth has some special books like George Seddon’s Sense of Place written in 1968, which set up planning for the next 50 years and is a brilliant combination of science and literary writing. Planning Boomtown and Beyond has 28 chapters on our city and covers the next 50 years after we realized we are going to be a big city after 400,000 people came here in 7 years during our recent boom. Most stayed as it’s a good city to live in. This book tries to keep it that way.

Buy the book.

Yolanda van Heezik, Dunedin

Yolanda van Heezik, Dunedin

Tāone tupu ora: Indigenous knowledge and sustainable urban design

by Stuart, K., & Thompson-Fawcett, M. (Eds.).

201

—How can traditional Māori built environments inform contemporary urban development?

—How could Māori values inspire our visions for the 21st century city?

—What can indigenous knowledge tell us about how to create a more sustainable design for the future?

Tāone Tupa Ora suggests answers to these important questions, by bringing together perspectives on a broad range of urban issues, from Māori development to architecture, town planning to strategic growth management. It collects stories of iwi experiences in the 21st century, and suggests principles and theories on which to base change. This book explores indigenous knowledge and sustainable development in New Zealand, reminding us of the importance of connection, respect and the role of spiritual knowledge in understanding how humans have interacted with the land over many centuries. It helps the reader to understand the origin of Māori values and their relationship with the land. It provides a set of principles for preserving culturally significant resources and landscapes to build community identity and participation. It compares Polynesian to European values with respect to housing and site design and shows how indigenous knowledge can be used to bring about sustainable planning and design. The book is easy to read, has useful illustrations and a glossary of Māori terminology.

Buy the book.

EUROPE

Isabelle Anguelovski, Barcelona

Isabelle Anguelovski, Barcelona

Urbanismo en el Siglo XXI

by Jordi Borja i Seabastiá and Zaida Martínez

2004

A critical analysis of the present and future urban development of European cities, through the lens of four Spanish case studies (Barcelona, Madrid, Valencia, and Bilbao). The right to a citizen’s centered urbanism is at the heart of the book and highlights the needs to build cities for people based on their individual and collective rights.

Buy the book.

Stephan Barthel, Stockholm

Stephan Barthel, Stockholm

Living cities – an anthology in urban environmental history

by Mattias Tegnér and Sven Lilja

2010

The Living City is about urban envrinmental history within some European cities and with 4 (hi)stories about Stockholm. A good read—read it to understand how we came up to where we are today.

Buy the book.

Nathalie Blanc, Paris

Nathalie Blanc, Paris

The Book of Disquiet

by Fernando Pessoa

2010

Translated by Margaret Jull Costa

Not being afraid of being tagged as a nostalgic urban lover, I would argue that Pessoa taught me that to have a good read on cities you needed to feel alive in their midst, meaning to feel powerful emotions, to long for impossible things, precisely because there is nothing there, and to resent yourself for it. You needed to desire what never was, and be dissatisfied at the city’s existence, and feel the potential for utopia. You could feel the numerous flux that impaired, defined the urban spaces and long intimately for them to stop or to be prolonged elsewhere. To paraphrase Pessoa, all these “half-tones of the soul’s consciousness create in us a painful landscape”, but also bond us with the pulsating urban spaces in a long term companionship.

Buy the book.

Lorenzo Chelleri, Barcelona

Lorenzo Chelleri, Barcelona

La Cittá nella storia d’Europa

by Benevolo Leonardo

1993

Not a recent book, but a fascinating account of Europe in the making through the lens of cities history and evolution. An Italian and European centred version of Lewis Mumford. The book was translated into English in 1995.

Buy the book.

Ian Douglas, Manchester

Ian Douglas, Manchester

Sustainable Urban Environments: An Ecosystem Approach

Ellen van Bueren, Hein van Bohemen, Laure Itard & Henk Visscher (Editors)

2012

Urban nature provides multi-functional benefits for life in towns and cities, but has to be fitted into the design and management of more sustainable human settlements. Europe has many examples of carefully planned low-carbon, resource efficient, livable cities that embrace ecosystem thinking, good governance and effective citizen participation. Holistic thinking about all aspects of urban infrastructure at different scales facilitates better integration of urban nature into the energy, water and materials fluxes and economic activities of cities.

Buy the book.

Emilio Fantin, Bologna

Emilio Fantin, Bologna

L’architettura del tempo. La città multimediale

by Sandra Bonfiglioli

1990

I suggest L’architettura del tempo (for those who can read italian). I appreciate the author’s point of view about architecture and urban planning. She has been working for years on the field of urban time policies in Italy. The book gives an overview of the time-oriented research. Since the beginning of the 20th century, time has been at the very core of the philosophical and scientific thinking showing revolutionary results. Sandra Bonfiglioli has extended this revolutionary force to the architecture and urban planning studies.

Buy the book.

Niki Frantzeskaki, Rotterdam

Niki Frantzeskaki, Rotterdam

Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas: Linkages between Science, Policy and Practice

Edited by Nadja Kabisch, Horst Korn, Jutta Stadler, Aletta Bonn (Editors)

2017

With many examples on how nature-based solutions change the urban features and how cities in Europe showcase the benefits to nature and to adapting to climate change. Why to read it? It is about European cities, it is about solutions that provide a brighter future for Europe and exemplify what other medium and large cities can do to enter a pathway for more sustainable and livable urban futures. Simpler: It is a book about solutions not problems.

Buy the book.

David Goode, Bath

David Goode, Bath

The Unofficial Countryside

by Richard Mabey

2010

My choice, published in 1973 by Collins with a new edition by Little Toller Books in 2010, is a seminal work of great significance it demonstrated the boundless capacity of nature to thrive in forgotten corners of towns and cities where a remarkable array of habitats including industrial wasteland, cemeteries, railsides, sewage farms and disused gravel pits support a multitude of species. Mabey turned our perception of town and country on its head. Though his examples came from personal experience of London the book is relevant in any urban setting. It was a profound milestone and remains a joy to read today.

Buy the book.

Gary Grant, London

Gary Grant, London

Ecourbanismo, Ciudad, Medio Ambiente Y Sostenibilidad, Segunda Edicion (Spanish Edition)

by Miguel Ruano

1998

The case studies are now dated, but this is an important milestone in the process of reconciling the once-conflicting ideologies of ecology and urban design. It has influenced many landscape architects.

Buy the book.

Christian Iaione, Rome

Christian Iaione, Rome

European Cities

by Patrick Les Galés

2002

It’s the most comprehensive but also trustworthy account on how European cities can thrive if they accept the challenge of facing social conflicts in cities through new urban governance approaches.

Buy the book.

François Mancebo, Paris

François Mancebo, Paris

La Ville sans Qualités (in French)

by Isaac Joseph

1998

Isaac Joseph gives precious insights into how people take ownership of public urban space: In his perspective living in a city is not only residing in it, but also to be constantly re-discovering it, relocating from one place to another, experiencing manifold territories, and finally changing oneself as well as transforming the city itself.

Buy the book.

Olivier Scheffer, Paris

Olivier Scheffer, Paris

Cities and Forms

by Serge Salat

Cities and Forms is a must-read for anyone interested in the morphogenetic laws of cities

Buy the book.

Chantal van Ham, Brussels

Chantal van Ham, Brussels

Making Urban Nature

by Piet Vollaard, Jacques Vink and Niels de Zwarte

2016

Making Urban Nature provides knowledge, guidance, practical advice and inspiring examples on nature-inclusive urban design in European cities. It describes various aspects of ecological design, highlighting many species and biotopes that can be found in cities useful for policy makers, practitioners. The book is of great value to everyone who would like to create space for nature in cities, while improving quality of life, but does not know how to start.

Buy the book.

Mike Wells, Bath

Mike Wells, Bath

Nature in Towns and Cities

by David Goode

2015

It most beautifully addresses and with passion the nature IN cities and starts at the end to talk about the nature OF them going forward. It rekindles ones love of the former and may start interest in many in the latter.

Buy the book.

LATIN AMERICA

Ana Luisa Artesi, Buenos Aires

Ana Luisa Artesi, Buenos Aires

Espacio Público en Imágenes. Paisaje, ciudad y arquitectura, una historia cultural de Buenos Aires. 1880 – 1910.

by Mirás Marta,

2013

Este libro es el resultado de la investigación en los registros de imágenes, notas e informes del Buenos Aires de fines del siglo XIX y principios del XX por la Dra. Marta Mirás. Teoría e Imágenes ilustran una era con profundas transiciones sociales, políticas y culturales. A través de sus páginas nos sumergimos en los complejos cambios de la estructura urbana y podemos comprender la evolución de una sociedad, su arquitectura y su paisaje, desde un entorno de aldea rural a una ciudad cosmopolita.

ENGLISH: This book is the result of the research in the image records, notes and reports of the Buenos Aires of the late ninetheen century and early twentieth by Dr. Marta Mirás. Theory and images illustrate an era with deep social, political and cultural transitions. Through its pages we immerse into the complex changes of the urban structure and we can understand the evolution of a society, its architecture and landscape, from a rural village setting to a cosmopolitan city.

Buy the book.

Eduardo Brondizio, Bloomington

Eduardo Brondizio, Bloomington

Rainforest Cities: Urbanization, Development, and Globalization of the Brazilian Amazon

by J. Browder and G GodFrey

1997

Rainforest cities brought international attention to the urban transformation of the Brazilian Amazon at a time when the conversation was mostly focused on the expansion of cattle ranching and deforestation in the region. Its publication, along with the work of Brazilian scholars, such as that of Berta Becker, spurred a wave of research on rural-urban networks, urban expansion, and the articulation (or disarticulation) of regional urban centers.

Buy the book.

Marcelo de Souza, Rio de Janeiro

Marcelo de Souza, Rio de Janeiro

O espaço dividido: Os dois circuitos da economia urbana dos países subdesenvolvidos

by Milton Santos

1979

O espaço dividido (“Shared Space”) was published originally in French by Milton Santos, Brazil’s most famous geographer, when he was living exiled in France. The book was later translated into Portuguese and English. This book is not concerned only about Latin American cities or urban problems, but with the so-called ‘two circuits’ of the urban economy of the ‘underdeveloped countries’ (as they were named in the 1960s and 1970s). The theory of the ‘two circuits’ challenged dualisms such as ‘modern’ versus ‘traditional’ on the basis of a dialectical approach that demonstrated how formality and informality are inextricably linked with each other, showing that poverty and informality are ultimately functional and useful in terms of the capitalist economy and reproduction of status quo.

Buy the book.

Anna Dietzsch, São Paulo

Anna Dietzsch, São Paulo

A Cidade Polifonia: Ensaio sobre a antropologia da comunicação urbana

by Massimo Canevacci

Studio Nobel, São Paulo

1993

In a very coloquial and creative way, the Italian anthropologist weaves his personal experience in São Paulo with an anthropological reading of the metropolis, placing before our eyes pieces of a puzzle that result in something like and emotional-analysis of the city through the superimposition of readings by Levi Strauss, Walter Benjamin, Italo Calvino and others. It results in one of the best descriptions of this “non-descriptive” megalopolis.

Buy the book.

Ana Faggi, Buenos Aires

Planificar la Ciudad. Estrategias para intervenir territorios en mutación

Planificar la Ciudad. Estrategias para intervenir territorios en mutación

Planning the City: Strategies to Intervene Territories in Change

by Guillermo Tella,

2014

El Dr. Arq. Guiilermo Tella examina a la ciudad como el espacio en el que la sociedad se reproduce, en el que los asentamientos humanos se expresan. Así mismo se pregunta de qué modo intervenir en estos complejos territorios en constante mutación. Ofrece estrategias para reconocer procesos de diferenciación de lugares y generar una mayor interacción física entre grupos que comparten el territorio. Con un ejemplo puntual, el de la ciudad de Lobos en la provincia de Buenos Aires, da muestra de que el planteo de la ciudad para todos más amigable, más saludable y equitativa es posible.

ENGLISH: Dr. Arq. Guiilermo Tella examines the city as the space in which society reproduces itself, in which human settlements express themselves. He also asks himself how to intervene in these complex territories in constant mutation. He offers strategies to recognize differentiation processes of places and to generate greater physical interaction between groups that share the territory. With a specific example, that of the city of Lobos in the province of Buenos Aires, he shows that the approach of a City for All, being more friendly, healthier and equitable is possible.

Buy the book.

Martha Fajardo, Bogotá

Martha Fajardo, Bogotá

Shaping Terrain: City Building in Latin America

by René Davids (Editor)

2016

Shaping Terrain focuses on the ways existing topography has shaped postcolonial urbanism, showing how physical landscape and local ecology influenced human settlement and built form in Latin America since pre-Columbian times.

Buy the book.

Cecilia Herzog, Rio de Janeiro

Cecilia Herzog, Rio de Janeiro

Brasil, Cidades – Alternativas Para a Crise Urbana

[in Portuguese]

by Hermínia Maricato

2011

This book is seminal to understand housing and social challenges that Brazilian cities face. The author has a critical knowledge about urban planning in the country, and she proposes alternatives for inclusive and just cities.

Buy the book.

Ian MacGregor-Fors, Xalapa

Aportes a la Ecología Urbana de la Ciudad de México [Contributions to the urban ecology of Mexico City]

by Eduardo Rapoport and Ismael R. López-Moreno

Aportes a la Ecología Urbana de la Ciudad de México [Contributions to the urban ecology of Mexico City]

by Eduardo Rapoport and Ismael R. López-Moreno

1987

This book is one of the first attempts to understand the ecological complexity of one of the most populated cities across the globe, providing a solid foundation for the currently growing urban ecology movement. From plants to birds, the editors guide readers to get to know the environmental part of such an interestingly complex asphalt jungle.

Buy the book.

Juliana Montoya, Bogotá

Juliana Montoya, Bogotá

Los árboles se toman la ciudad, El proceso de modernización y la transformación del paisaje en Medellín, 1890-1950

by Diego Alejandro Molina Franco

2015

A través de este libro, se puede comprender el proceso de la modernización de la ciudad de Medellín a través de las posturas y percepciones de ese momento frente a los árboles, desde la experimentación, simbolismo, adaptaciones y la ornamentación vegetal típicos de esa epoca. Este libro es la construcción de lo que conocemos hoy como la naturaleza de la ciudad de Medellín. http://www.universocentro.com/ExclusivoWeb/ImpresosLocales/Losarbolesetomanlaciudad.aspx

Buy the book.

José Puppim, Rio de Janeiro

José Puppim, Rio de Janeiro

Confidência do Itabirano (Confidences of an “Itabirano”)

A poem from Carlos Drummond de Andrade, Brazil’s best poet, written in his 1940’s book Sentimento do Mundo (The Feeling of the World) with his feelings about the changes in the world, including his home town. This is one of my favorites poems. The poem is about the landscape changes since his childhood in Itabira, his home town in the State of Minas Gerais, due to iron ore mining (Itabira is home of one of the iron ore’s largest mines operated by Vale, a Brazilian mining company that caused the worst environmental tragedy in Brazil in 2015). The poem, allied to the recent tragedy, shows that development aiming at short term lead to long term problems.

Read the poem here.

Buy the book.

Raul Pacheco-Vega, Aguascalientes

Raul Pacheco-Vega, Aguascalientes

Water and Politics: Clientelism and Reform in Urban Mexico

by Veronica Herrera

In Water and Politics, Herrera analyzes the politics of urban water provisioning in eight Mexican cities. Undertaking extensive (2.5 years) fieldwork, Herrera shows how politicians manipulate water provision in cities for electoral gain. Through in-depth interviews and process tracing techniques, Veronica Herrera demonstrates that elites are able to manipulate how water is governed in cities. Even more importantly, Herrera’s insights can be translated to other Latin American countries and sub-national contexts.

Buy the book.

Luis Sandoval, San José

Luis Sandoval, San José

Land Use Change in Costa Rica: 1966-2006, as influenced by social, economic, political, and environmental factors

by Joyce, A. T.

2006

This book is a very good introduction on how the land use change over a 40 year period in a tropical country after population growth. Additionally, the book makes comparisons between different ecosystems and elevations showing how the land use change is not equally distributed throughout different ecosystems.

Buy the book.

Diana Wiesner, Bogotá

Diana Wiesner, Bogotá

Naturaleza Urbana. plataforma de experiencias

edited by María Angélica Mejía

2016

Es necesario contemplar las acciones concretas de la Ciudadanía respecto al cuestionamiento del papel de la naturaleza en la ciudad. Los gobiernos locales subestiman el poder de la acción ciudadana. Uno de los potenciales más poderosos es la capacidad que puede tener una complicidad público privada para una gestión efectiva de la biodiversidad en la transformación positiva de las ciudades. Este libro se logró gracias a la participación de más de 80 casos en diversos lugares de Colombia.

The Spanish version of the book can be downloaded here. Also available in English.

Lorena Zárate, Mexico City

Lorena Zárate, Mexico City

Jueces y conflictos urbanos en América Latina

by Antonio Azuela y Miguel Ángel Cancino (Coordinadores)

2014

Almost by definition, urban means high levels of complexity and conflict. What are the tools that different social actors (citizens, communities and activists, professionals, academics, public officials, legislators, lawyers and judges) have at hand to deal with them? What are the gaps, contradictions and overlapping between the approaches from social sciences, domestic regulations and international human rights commitments? This book presents a fascinating collage of a relevant current debate about the urban transformation in many Latin American countries and the role of law in creating more just and inclusive cities.

Buy the book.

NORTH AMERICA (not including Mexico)

Will Allen, Chapel Hill

Will Allen, Chapel Hill

Green Metropolis: Why Living Smaller, Living Closer, and Driving Less Are the Keys to Sustainability

by David Owen

2010

I liked this book, because it kind of turns environmentalism on its head. Compact urban centers actually are the most environmentally friendly option for people and nature, and this book makes a great case for that.

Buy the book.

Adrian Benepe, New York

Adrian Benepe, New York

Motherless Brooklyn

By Jonathan Lethem

2000

It is set in and summons up the pre-gentrification Downtown Brooklyn and Gowanus, it all its gritty glory It features an unlikely protagonist, one of the most memorable private detectives in the business, Lionell Essrog, who is afflicted with Tourette Syndrome, and can’t halt either nerves tics or a steady stream of involuntary, hilarious obscenity.

Buy the book.

Carmen Bouyer, New York

Carmen Bouyer, New York

Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City

by EricSanderson

2013

Mannahatta has introduced me to New York City like no other book did. I discovered the very poetic of this place through understanding its ancient forests, groves, rivers, creeks and the widely divers fauna of fishes, mammals and birds migrating through it, at sea, on the land, and in the air, like I just did myself, flying to this new land. In fact, I think every city needs its Mannahatta project, to excavate the wisdom of the land upon which the cities are built, and let it inform how to regenerate and expand its organic forms in the cities of tomorrow.

Buy the book.

Rebecca Bratspies, New York

Rebecca Bratspies, New York

The Death and Life of Great American Cities

by Jane Jacobs

1961

This book is a timeless love letter to great cities and urban life. It provides a critical reminder of the law of unintended consequences, and a cautionary tale for why theories, especially theories about urban environments must always be reality tested.

Buy the book.

Lindsay Campbell, New York

Lindsay Campbell, New York

The Environment and the People in American Cities, 1600s-1900s: Disorder, Inequality, and Social Change

by Dorceta Taylor

This book covers a long historical arc, from 1600-1900, focusing on the development of the urban environment and urban environmentalism. Taylor draws attention to activism, community organizing, reformers, and environmental justice work. She examines persistent environmental inequities and conflicts that shape our urban realm, as well as the role of residents, particularly communities of color, in transforming these systems.

Buy the book.

Katie Coyne, Austin

Katie Coyne, Austin

Rubyfruit Jungle

by Rita Mae Brown

What is urbanism? Rather than speak of a collective version of urbanism – my version is one that thrives on connections between people and place and is focused on the intersectional opportunities design and planning provides. My intersectional identity is a driving factor in my evolving understanding of systems thinking – a concept central to my urban ecology work. I read Rubyfruit Jungle when I was an undergraduate student. It tells a nitty gritty story of my foremothers and chronicles the social dynamic of growing up a lesbian in Florida in the 1970s, the initial escape to higher education (which just so happens to be at my alma mater), and the eventual journey to the “big city” in a time when migration to urban life was common when the anonymity it provided was of more relevance to queer physical safety and long term happiness. This book offered me a window into a historic (and still ongoing) reality of systemic discrimination against people like me and gave me perspective on the cultural importance of urban spaces today.

Buy the book.

Sarah Dooling, Austin

Sarah Dooling, Austin

The Odd Woman and the City: A Memoir

by Vivian Gornick

2016

Gornick’s memior is located in New York City, and she described how the city became part of her sense of self and the friendships she shares with other New Yorkers. Loneliness, emotional connectivity, the power of space to create containers for life experiences are the main themes. New York emerges as protagnoist, changing physically and socially, as Gornick’s incisive commentary about urban life and the friendships she sustains as she ages intersects with descriptions of urban change more broadly.

Buy the book.

Richard T.T. Forman, Boston

Richard T.T. Forman, Boston

Urban Ecology: Science of Cities

by Richard T. T. Forman

2014

For thirty years pioneering ecologists have explored urban areas, both as a promising scientific frontier and as places crying out for improvement. Urban Ecology: Science of Cities, the first comprehensive book on the subject, was a finalist for the Society of Biology (London) Book Award and now a Chinese Edition strategically spreads the book’s messages. Dig into the pages, and gain a new vision of life today and tomorrow, with and without nature, for most of us on Earth.

Buy the book.

Sheila Foster, New York

Sheila Foster, New York

The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York

by Robert Caro

1975

The Powerbroker is the ultimate introduction to understanding the semi- public, semi-private nature of city building in the United States. The story of Robert Moses, a bureaucrat who oversaw numerous public authorities and massive amounts of public funding while mobilizing the private and nonprofit sectors, is an instructive but cautionary tale of urban resurgence and subsequent urban decline. It is a revealing and riveting read about how power works in U.S. cities which remains quite relevant today.

Buy the book.

Mathieu Hélie, Montreal

Mathieu Hélie, Montreal

The Geography of Nowhere: The Rise and Decline of America’s Man-Made Landscape

by James Howard Kunstler

1993

The Geography of Nowhere presents the real outcome of the utopian ideals of modernist suburbanization as a tragedy, and its eventual metamorphosis into the driving economic engine of all America as a doomed project. It is a prophetic book that future generations will study to attempt to understand the confusing origins of their landscape as they struggle to repair it.

Buy the book.

Steven Handel, New Brunswick

Steven Handel, New Brunswick

A Natural History of New York City

by John Kieran

John Kieran’s classic 1959 book discusses simply but in detail the vast natural resources and biodiversity of the city to which most residents are totally blind. New York is the largest metropolitan area in North America, but even there the pockets of habitat that remain, many “degraded” to a naturalist’s eye, harbor thousands of species and vary in character from marine coast to rocky upland crevices. The book forces us to rethink the dichotomy between “nature there, city here” into “nature is all around us; Broadway is alive.” And if NYC is alive, what about all those other North American cities??

Buy the book.

Ursula K. Heise, Los Angeles

Ursula K. Heise, Los Angeles

New York 2140

Kim Stanley Robinson

2017

Robinson’s most recent science fiction novel delivers a lively portrait of a still vibrant Manhattan that’s been hit by 50 feet of sea level rise by the year 2140. Buildings collapse, and others rise up. Real estate speculation still exists, Wall Street still exists, Internet celebrities still ply their trade: and the need for social and economic reform also continues, and triggers a surprising turn in the plot.

Buy the book.

Mark Hostetler, Gainesville

Mark Hostetler, Gainesville

The Green Leap: A Primer for Conserving Biodiversity in Subdivision Development

by Mark Hostetler

2012

I think this book is an easy read for interested folks wanting to shift conventional development to alternative development that conserves biodiversity. Targeting many urban decision makers, including developers, environmental consultants, city planners, and the public, this book gives examples and strategies to create functional conservation developments. It explains the challenges and solutions during the design, construction, and postconstruction phases of development that is required to conserve biodiversity.

Buy the book.

Mike Houck, Portland

Mike Houck, Portland

The Last Landscape

by William H. Whyte

1970

Whyte builds a rationale for protecting natural landscapes at the local, city and regional scales based on their importance to human health, ecological sustainability, economic health and quality of life. He traces the evolution of open space planning in the U. S. and builds a solid case for regional planning. While written in the 1960s The Last Landscape is even more relevant today in the face of the need for mitigating and adapting to climate change by making the case for integration of natural systems, what today we refer to as natural and built green infrastructure into the urban landscape.

Buy the book.

Nina-Marie Lister, Toronto

Nina-Marie Lister, Toronto

The Granite Garden: Urban Nature And Human Design

by Anne Whiston Spirn

1984

A classic, beautifully written and illustrated, one of the first books to effectively link landscape, ecology and urban infrastructure. As a landscape architect, Anne Spirn reveals how making legible landscape and ecological functions can lead to nature-based solutions that remediate and heal environmental problems of the city.

Buy the book.

Rob McDonald, Washington

Rob McDonald, Washington

The Geography of Nowhere: The Rise and Decline of America’s Man-Made Landscape

by James Howard Kunstler

1993

What I love about this book is that it centers its critique of suburbia around the idea of the common good, and of what kind of world we want to live in. As I research and advocate for more natural infrastructure in cities, as part of the agenda of making them thriving places to live, I find this frame really powerful. We are creating the cities of the future, now, and Kunstler reminds us it is a moral choice, a choice that shows what we truly value.

Buy the book.

Charles H. Nilon, Columbia

Charles H. Nilon, Columbia

Fitzgerald: Geography of a Revolution

Bunge, William. 1971

2011

William Bunge was an urban geographer who during his years as professor at Wayne State University developed an intensive study of the one square mile Fitzgerald neighborhood. The project was part of the Detroit Geographical Expedition and Institute, an extension course offered to inner city Detroit residents. The study was designed to be a study conducted by Fitzgerald residents to inform the about where they live and also to meet their needs in changing their neighborhood and city. The book is a product of that study and in current urban ecology terms it is a study of a complex social-ecological system. It combines physical geography, ecology, urban history, urban sociology and urban planning. However the book is much because it illustrates the power and potential of urban residents designing and conducting a study of where they live. It also has an optimistic tone that values the inner city and its residents that is missing from much of the current literature on the ecology of cities.

Buy the book.

Steward Pickett, Poughkeepsie

Steward Pickett, Poughkeepsie

The Nature of Cities: Ecological Visions and the American Urban Professions, 1920-1960

Jennifer S. Light

2009

This book is important to me because it uses rigorous historical analysis to examine how ecology was (mis)used as a metaphor by the Chicago School of urban sociology in the 1920s, and how the misunderstandings resonated in policy well into the 1960s. It is also important for reminding us that not only social sciences and urban planning are key bridge professional links for ecology, but also that the real estate industry is key causal factor in the shape of urban areas and, hence, their ecology.

Buy the book.

Rob Pirani, New York

Rob Pirani, New York

Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West

by William Cronon

1992

Cronon’s opus shows how urbanization, landscape and economy combined to shape the “City of Broad Shoulders” and the settlement of the continent. It is a richly detailed trove of urban environmental history as well as a great testament to the importance of regionalism in shaping cities and nature.

Buy the book.

Toby Query, Portland

Toby Query, Portland

Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors

by Carolyn Finney

2014

Finney provides a personal and academic history of race and the environment (focusing on African Americans and whites) in the U.S. Although not focused on cities, this book highlights the need for the inclusion of the diversity of cultures and histories when advocating for and designing public space. As a manager of urban greenspaces, I think it’s essential reading for people that want to create just and equitable environments, in the woods or the urban core.

Buy the book.

Stephanie Pincetl, Los Angeles

Stephanie Pincetl, Los Angeles

Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West

by William Cronon

1992

Cronon explains how cities emerge from their landscapes and then harness and capture those landscapes to further their development. He further explains how Chicago, in the case, and the emerge of the railroad, rationalise the landscape and lead to a deep transformation of space and time. Chicago’s development, intertwined with the rise of the railroad, transformed a good part of the great plains and corresponding livelihoods. The book provided a new way of thinking about cities and landscapes.

Buy the book.

Mary W. Rowe, Toronto

Mary W. Rowe, Toronto

Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software

by Steven Johnson

2001

Johnson provides a brilliant analysis of self-organizing systems that occur in nature and in human creations, including cities.

Buy the book.

Laura Shillington, Montreal

Laura Shillington, Montreal

Reclaiming Indigenous Planning

edited by Ryan Walker, Ted Jojola and David Natcher

McGill-Queen’s University Press

2013

Why do I think that everyone (involved in planning and urban development) in North America should read this book? Urban planning, as most contributors to Nature of Cities have underscored, is a political process. Conventional urban planning in North America is guided by European understandings of development and cities. Yet while many cities in North America were founded on Indigenous trading sites and villages, they have been developed around the belief that Indigenous peoples do not belong in urban areas. Reclaiming Indigenous Planning challenges the socio-political and ecological foundations of conventional planning, asking the questions: what is being planned, why and for whom? These are critical questions that need to be asked, in particular within the Canadian urban landscape where the Indigenous population is one of the fastest growing urban demographic. As the editors of state in their introduction, the book “calls for more critical understandings of what planning entails and how the ideas and visions of Indigenous communities can best be captured in future planning processes” (p. xix). Reclaiming Indigenous Planning is edited volume with chapters on Canada and the United States as well as Australia and New Zealand. Sections I and II will be of particular interest to urban planners. My favourite chapters are Chapter 3, which discuss planning as a tool for dialogue between Indigenous and settler communities, and Chapter 12, which focuses on the power of statistics in planning – how statistics can be transformative. I would argue that this book should be required reading in urban planning programmes across Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand. http://www.mqup.ca/reclaiming-indigenous-planning-products-9780773541948.php

Buy the book.

Jay Valgora, New York

Jay Valgora, New York

Views and Viewmakers of Urban America: Lithographs of Towns and Cities in the United States and Canada, Notes on the Artists and Publishers, and a Union Catalog of Their Work, 1825-1925

by John W Reps

1986

First, it’s hard to find a book for North America, as one wants to give justice to all the countries of North America, which is difficult for a good book on urbanism (unfortunately). This book at least covers both Canada and the United States. But more importantly it focuses on evidence rather than theory- and uses a denigrated but highly useful art form (lithographs and aerial views) to tell the story of urbanism in both countries at one of its periods of both greatest expansion and invention. It focuses equally on large and small cities, illustrating greater interest in ambition, typology, variation, and representation— rather than simply scale. One of the best.

Buy the book.

You say po-TAY-to. What ecologists and landscape architects don’t get about each other, but ought to.

You say po-TAY-to. What ecologists and landscape architects don’t get about each other, but ought to.

Gina Avlonitis, Cape Town

Gina Avlonitis, Cape Town Pippin Anderson, Cape Town

Pippin Anderson, Cape Town Kobie Brand, Thea Buckle, Jessica Kavonic, Michelle Preen & Meggan Spires, Cape Town

Kobie Brand, Thea Buckle, Jessica Kavonic, Michelle Preen & Meggan Spires, Cape Town Katrine Claassens, Montreal

Katrine Claassens, Montreal Nadja Kabisch, Berlin

Nadja Kabisch, Berlin Shuaib Lwasa, Kampala

Shuaib Lwasa, Kampala Susan Parnell, Cape Town

Susan Parnell, Cape Town Elisabeth Peyroux, Paris

Elisabeth Peyroux, Paris Debra Roberts, Durban

Debra Roberts, Durban David Simon, Gothenburg

David Simon, Gothenburg Xuemei Bai, Canberra

Xuemei Bai, Canberra Timothy Bonebrake, Hong Kong

Timothy Bonebrake, Hong Kong Bharat Dahiya, Bangkok

Bharat Dahiya, Bangkok P.K. Das, Mumbai

P.K. Das, Mumbai Haripriya Gundimeda, Mumbai

Haripriya Gundimeda, Mumbai Fadi Hamdan, Beirut

Fadi Hamdan, Beirut Keitaro Ito, Kyushu

Keitaro Ito, Kyushu Alpana Jain, Delhi

Alpana Jain, Delhi Maggie Lin, Hong Kong

Maggie Lin, Hong Kong Patrick Lydon, Osaka

Patrick Lydon, Osaka Anjali Mahendra, Delhi

Anjali Mahendra, Delhi Mahim Maher, Karachi

Mahim Maher, Karachi Jala Mahkzoumi, Beirut

Jala Mahkzoumi, Beirut Harini Nagendra, Bangalore

Harini Nagendra, Bangalore Daniel Phillips, Bangalore

Daniel Phillips, Bangalore Mohan Rao, Bangalore

Mohan Rao, Bangalore Karen Seto, New Haven

Karen Seto, New Haven Huda Shaka, Dubai

Huda Shaka, Dubai Keijiro Suzuki, Yamaguchi

Keijiro Suzuki, Yamaguchi Steve Brown, Sydney

Steve Brown, Sydney Meredith Dobbie, Victoria

Meredith Dobbie, Victoria Paul Downton, Melbourne

Paul Downton, Melbourne Amy Kristin Hahs, Ballarat

Amy Kristin Hahs, Ballarat Peter Newman, Perth

Peter Newman, Perth Yolanda van Heezik, Dunedin

Yolanda van Heezik, Dunedin Isabelle Anguelovski, Barcelona

Isabelle Anguelovski, Barcelona Stephan Barthel, Stockholm

Stephan Barthel, Stockholm Nathalie Blanc, Paris

Nathalie Blanc, Paris Lorenzo Chelleri, Barcelona

Lorenzo Chelleri, Barcelona Ian Douglas, Manchester

Ian Douglas, Manchester Emilio Fantin, Bologna

Emilio Fantin, Bologna Niki Frantzeskaki, Rotterdam

Niki Frantzeskaki, Rotterdam David Goode, Bath

David Goode, Bath Gary Grant, London

Gary Grant, London Christian Iaione, Rome

Christian Iaione, Rome François Mancebo, Paris

François Mancebo, Paris Olivier Scheffer, Paris

Olivier Scheffer, Paris Chantal van Ham, Brussels

Chantal van Ham, Brussels Mike Wells, Bath

Mike Wells, Bath Ana Luisa Artesi, Buenos Aires

Ana Luisa Artesi, Buenos Aires Eduardo Brondizio, Bloomington

Eduardo Brondizio, Bloomington Marcelo de Souza, Rio de Janeiro

Marcelo de Souza, Rio de Janeiro Anna Dietzsch, São Paulo

Anna Dietzsch, São Paulo Planificar la Ciudad. Estrategias para intervenir territorios en mutación

Planificar la Ciudad. Estrategias para intervenir territorios en mutación Martha Fajardo, Bogotá

Martha Fajardo, Bogotá Cecilia Herzog, Rio de Janeiro

Cecilia Herzog, Rio de Janeiro Aportes a la Ecología Urbana de la Ciudad de México [Contributions to the urban ecology of Mexico City]

by Eduardo Rapoport and Ismael R. López-Moreno

Aportes a la Ecología Urbana de la Ciudad de México [Contributions to the urban ecology of Mexico City]

by Eduardo Rapoport and Ismael R. López-Moreno Juliana Montoya, Bogotá

Juliana Montoya, Bogotá José Puppim, Rio de Janeiro

José Puppim, Rio de Janeiro Raul Pacheco-Vega, Aguascalientes

Raul Pacheco-Vega, Aguascalientes Luis Sandoval, San José

Luis Sandoval, San José Diana Wiesner, Bogotá

Diana Wiesner, Bogotá Lorena Zárate, Mexico City

Lorena Zárate, Mexico City Will Allen, Chapel Hill

Will Allen, Chapel Hill Adrian Benepe, New York

Adrian Benepe, New York Carmen Bouyer, New York

Carmen Bouyer, New York Rebecca Bratspies, New York

Rebecca Bratspies, New York Lindsay Campbell, New York

Lindsay Campbell, New York Katie Coyne, Austin

Katie Coyne, Austin Sarah Dooling, Austin

Sarah Dooling, Austin Richard T.T. Forman, Boston

Richard T.T. Forman, Boston Sheila Foster, New York

Sheila Foster, New York Mathieu Hélie, Montreal

Mathieu Hélie, Montreal Steven Handel, New Brunswick

Steven Handel, New Brunswick Ursula K. Heise, Los Angeles

Ursula K. Heise, Los Angeles Mark Hostetler, Gainesville

Mark Hostetler, Gainesville Mike Houck, Portland

Mike Houck, Portland Nina-Marie Lister, Toronto

Nina-Marie Lister, Toronto Charles H. Nilon, Columbia

Charles H. Nilon, Columbia Steward Pickett, Poughkeepsie

Steward Pickett, Poughkeepsie Rob Pirani, New York

Rob Pirani, New York Toby Query, Portland

Toby Query, Portland Mary W. Rowe, Toronto

Mary W. Rowe, Toronto Laura Shillington, Montreal

Laura Shillington, Montreal Jay Valgora, New York

Jay Valgora, New York

Add a Comment

Join our conversation