ESSAYS | POINTS OF VIEW

-

Learning Climate Lessons from my 5-year-old

I heard the worried tone in Mía’s voice when she said, “This feels a little like a movie.” I was cooking us dinner while she watched a cartoon…

-

Urban Mini-forests Can Reinvent How Cities Grow, Learn, and Respond to Climate Stress

Sunlight hits the concrete courtyard of a large public school complex in the northern outskirts of São Paulo, Brazil. It is a dense urban area with few trees…

-

Living and Working as Biodiversity

Soon after the turn of the century, James Miller wrote a couple of important articles on urban biodiversity. The first argued that conservation biology needs to focus more…

TNOC’S MISSION

Cities and communities that are better for nature and all people, through transdisciplinary dialogue and collaboration.

We combine art, science, and practice in innovative and publicly available engagements for knowledge-driven, imaginative, and just green city making.

SUPPORT BETTER CITIES,

JOIN OUR NETWORK OF DONORS…

REVIEWS | ART, BOOKS & EVENTS

-

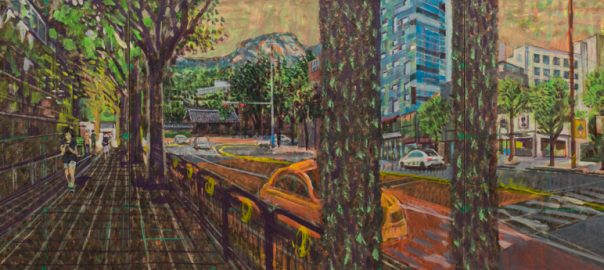

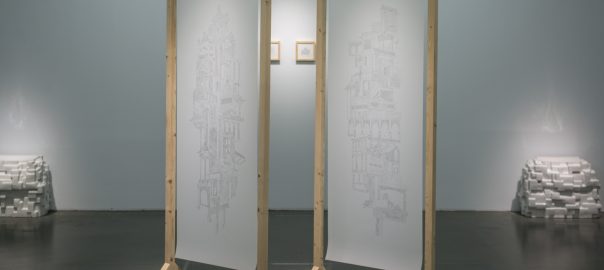

What Remains?

A review of Ghost Ships and Mourning Doves, a multimedia art exhibition by Robin Lasser and Sydney Brown, on view October 1 ― December 13, 2025 at Chung…

PROJECTS | ART, SCIENCE & ACTION, TOGETHER

NBS COMICS: NATURE TO SAVE THE WORLD

26 Visions for Urban Equity, Inclusion and Opportunity

Now a global project with over ONE MILLION readers, we invite comic creators from all over the world to combine science and storytelling with nature-based solutions (NBS).

JOIN THOUSANDS OF READERS

AROUND THE WORLD…

MORE TNOC PROJECTS | ART, SCIENCE & SOCIAL JUSTICE

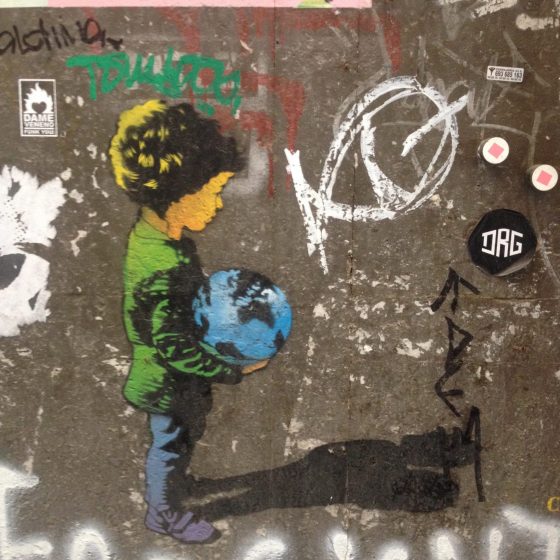

THE NATURE OF GRAFFITI

This is the nature of graffiti. It facilitates speech. It speaks to us. It stakes claims and makes statements. It tells stories.

The Nature of Cities hosts a public gallery about the graffiti and street art that motivates us in public places.

the roots of cool

As the world warms up, how are you thinking about the role that trees and shade can play in making your city or region livable?

Read and listen to the stories in this global collaboration between The Nature of cities & Descanso Gardens.