Regularly, we feature a Global Roundtable in which a group of people respond to a specific question in The Nature of Cities.

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David's dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to "fall back on". So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

We have assembled a list of 90 must-reads on cities from a diverse group of TNOC contributors—a nature of cities reader’s digest. The recommendations are as wide-ranging as the TNOC community, from many points of view and from around the world. They are a reflection of the breadth of thought that cities need. And, as my grandmother would have said: “This will keep you off the street and out of trouble”.

The prompt seems easy, but it turns out to be difficult to recommend the one thing everyone should read on cities, and what we have created here is a remarkable and diverse reading list. You will likely think of other essential works yourself, and when you do, leave them here as a comment. There is a rich conversation to experience simply by exchanging ideas on great books.

The list below could serve as a wonderful primer for courses or other gatherings. You can download the entire list as a PDF here.

Check out these titles at your local, corner bookstore. But if you choose to buy one of these titles online, please click here to go to Amazon . Some of the sales price will benefit TNOC.

. Some of the sales price will benefit TNOC.

The books are listed in a random order. Refresh your screen to see the list displayed in a different order.

Get busy.

—David Maddox

Pippin Anderson, Cape Town

Pippin Anderson, Cape Town

Rambunctious Garden: Saving Nature in a Post-Wild World

by Emma Marris

2011, Bloomsbury USA

Touches critically on so many debates in ecology (well, in many quarters they are not debated). Re-wilding, novel ecosystems, are invasive aliens always bad, old conservation models … etc. Her writing feels effortless and then she gives you lots to kick back against. Rather like finding yourself eating an exotic flavour of ice cream (ice cream—yum, popcorn flavoured—gosh!).

Buy the book.

Gloria Aponte, Medellín

Gloria Aponte, Medellín

Cities and Natural Process

by Michael Hough

1995, Routledge

Nobody concerned with urban habitat should miss this book, available in English and in Spanish, that reaffirms the role of nature in the city. In six easy to read chapters, landscape as a process is highlighted and understood as the link between nature, humans, and built environment. The author demonstrates that total control (of nature) is impossible and that in attempts to do it, the result is least diversity for the most effort.

Buy the book.

Ana Luisa Artesi, Buenos Aires

Ana Luisa Artesi, Buenos Aires

Horizon 101 – Reflections and Paintings

by Jala Makhzoumi

2010, Dar Onboz

I strongly recomend Jala Makhzoumi’s “101 horizons”, for students and people involved in Landscape in cities as a fundamental reading to see a different point of view.

From a room with a view of the Mediterranean, in an artistic and emotional story, with poetry and illustrations, and also … blank spaces, Jala describes a Landscape where all Theories and Methodologies are surpassed by the day to day of a terrible and seemingly endless war. Despite all the fears, Jala paints, draws, dreams, wishes … expressing from her soul, so that we can understand the depth of this moment.

The text in both languages, Arabic and English.

Xuemei Bai, Canberra

Xuemei Bai, Canberra

王如松:《高效、和谐–城市调控原理与方法》, 湖南教育出版社, 1988, 278页.

Efficiency and Harmony: Principles and methods of urban system regulation and control

by Rusong Wang

1988, Hunan Education Publisher

Rusong Wang is an internationally renowned urban system ecologist, whose work laid the foundation of urban ecology research in China, and influenced and contributed greatly to the theory and practice of eco-city development in China. Although not always highly cited in the English literature, some of the concepts and thoughts presented in this book—e.g., cities as complex social-economic-ecological systems—were inspirational in the 1980s and are cutting edge even today. Nominating this book is also a way to pay tribute to a fine urban scholar and his achievement—he passed away in 2014 at the age of 67.

Stephan Barthel, Stockholm

Stephan Barthel, Stockholm

The Death and Life of Great American Cities

by Jane Jacobs

1961, Random House

It opens up a view of the city as an ecosystem. It is a must read for anyone combating the “hot planning topic of densification”. Such an agenda builds, to some degree, on Jacobs’ thinking—but with a selective interpretation of it. She was one of the first describing how social capital is built in neighborhoods in large cities, and one of the first describing how the gentrification process works (but long before any of those terms were theorized). She lacked an understanding about the benefits humans obtain by interacting with natural environments, which is her drawback. But hey, no one is perfect. Great book, great humanist, and great systems thinker!

Buy the book.

Jane Battersby, Cape Town

Jane Battersby, Cape Town

Hungry City

by Carolyn Steel

2008, Random House

Food fundamentally shapes our cities’ ecologies, economies, and social lives, but most people hardly ever consider how it reaches our plates in cities. Hungry City traces food from farm to fork and beyond. It will not only make you look at food in a new way, but will give you a new perspective on cities; as Steel herself says, “In order to understand cities properly, we need to look at them through food”.

Buy the book.

Adrian Benepe, New York

Adrian Benepe, New York

The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York

by Robert Caro

1975, Knopf Doubleday

The Power Broker by Robert Caro, and not necessarily as a pro Jane-Jacobs morality tale.

For example, Robert Moses tripled the NYC park system in size—the biggest periods of park creation and expansion in NYC’s history.

Buy the book.

Genie Birch, Philadelphia & New York

Genie Birch, Philadelphia & New York

The Works: Anatomy of a City

Kate Ascher

2007, Penguin Press

Kate Ascher introduces this portrait of urban infrastructure based on New York City with a wise observation: “Rarely does a resident of any of the world’s great metropolitan areas pause to consider the complexity of urban life or the myriad systems that operate around the clock to support it.” She then offers a richly illustrated compendium that explains five systems: transport of people and freight, power, communications, water, and sanitation. While slightly outdated due to the absence of a current description of today’s technology, it is an accessible and informative primer. The final chapter, “The Future,” lays out key concerns.

Buy the book.

Timothy Bonebrake, Hong Kong

Timothy Bonebrake, Hong Kong

The Ecology of a City and its People: The Case of Hong Kong

by S. Boyden, S. Millar, K. Newcombe, and B. O’Neill

1981, Australian National University Press

This is a classic book in urban ecology that examines the city from an ecosystem perspective, with humans as a key and integral component of the ecosystem. In the 35 years since the book was published, Hong Kong has changed dramatically in many ways, including a 40 percent increase in population size and skyrocketing rates of consumption—this book provides a fascinating source of perspective in light of these changes. While some of the specific conclusions may well be unique to Hong Kong, the general patterns are largely applicable to growing cities worldwide.

Buy the book.

Eduardo Brondizio, Bloomington

Eduardo Brondizio, Bloomington

Dreaming Equality:

Color, Race, and Racism in Urban Brazil

by Robin Sheriff

2001, Rutgers University Press

An ethnographic analysis of race relations from the perspective of residents of a Rio favela.

Buy the book.

Steve Brown, Sydney

Steve Brown, Sydney

Stories from the Sandstone: Quarantine Inscriptions from Australia’s Immigrant Past

Peter Hobbins, Ursula K Frederick and Anne Clarke

2016, Arbon Publishing

This newly published book is an archaeological-historical investigation of rock inscriptions at Sydney’s former Quarantine Station (1835 – 1979). It charts stories of new arrivals to Australia and the diseases that saw them held at this place for days, weeks, and months. I recommend it for its multiple narratives of the growth of Sydney as an urban, ethnically diverse, and spectacular city from immigration and medical perspectives.

Lena Chan, Singapore

Lena Chan, Singapore

Design With Nature

by Ian McHarg

1969, Natural History Press

A must-read book. Inspirational. I first read it in 1981, still find it relevant, and always discover something new each time I re-visit it.

Buy the book.

Lindsay Campbell, New York

Lindsay Campbell, New York

Crabgrass Frontier

by Kenneth Jackson

1985, Oxford University Press

Because to understand the city, we have to understand the suburb. While conditions have changed since this 1985 book, Jackson investigates the role of multiple forces, including technology, transportation, federal policy, culture, and demographic shifts in shaping the suburban form of the United States. I read it as an undergrad in my first geography course, and this book sparked my interest in studying urban planning and later human geography. Particularly insightful is his chapter on early federal policies—such as the Federal Highway Act, Home Owners Loan Corporation (origin of redlining), and the Federal Housing Act, showing the institutionalized roots of spatial unevenness and inequality in our urban and suburban form.

Buy the book.

Lorenzo Chelleri, L’Aquila

The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects

The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects

by Lewis Mumford

1961, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

There is no book like this in addressing how and why cities evolved, from the medieval villages to the modern post-industrial metropolis. Mumford was among the few able to grasp and communicate, through a clear and extraordinary narrative style, the very “nature” of cities, explaining the root causes of the processes which remain at the forefront of urban studies debates. His half century old insights explain most of the problem we’re still facing and about which any reader could deepen her knowledge with hundreds of books. But no other book could provide you the big picture, the bases for understanding “what is a city”.

Buy the book.

Katrine Claassens, Cape Town

Katrine Claassens, Cape Town

Preludes

by T.S. Eliot

1911

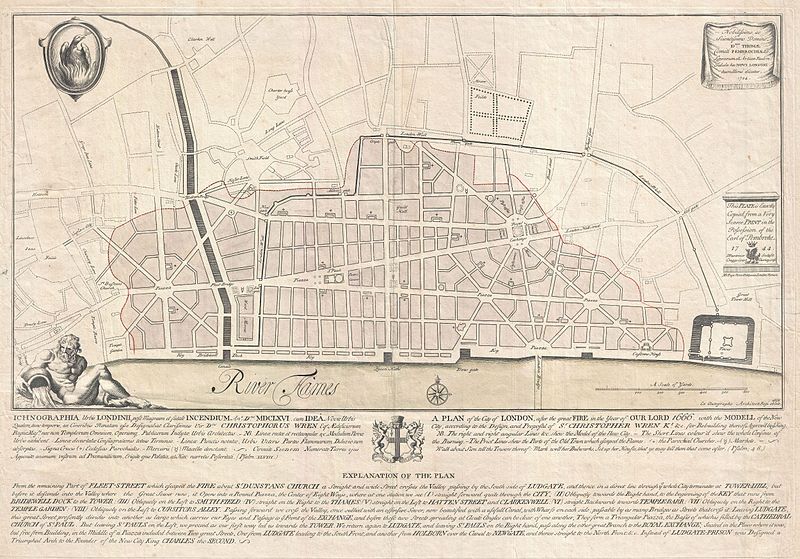

Now more than 100 years old, this poem is a haunting look at a turn-of-the-century city, which—despite its description of a London where cab horses “steam and stamp” and lamps must still be manually lit—is shockingly modern. In a smoky, densely populated city, nature lingers, clinging uneasily, with “sparrows in the gutters” and vacant lots offering fuel for fires.

Buy the book.

Bharat Dahiya, Bangkok

Bharat Dahiya, Bangkok

Banaras: Making of India’s Heritage City

by Rana P.B. Singh

2009,

Cambridge Scholars Publishing

Based on more than three decades of intensive research and intimate acquaintance with the sacred geography and urban cultural history of India’s ancient living city, Professor Rana P.B. Singh, in this pioneering volume, provides an excellent narrative of the making of Banaras—also known as Kashi or Varanasi. This book is a lead reference for understanding the cultural landscape, sacred geometry and cosmogram, archetypal architecture, vivid ritualscapes, and magnificent riverfront heritagescapes of Banaras that portray and maintain the dignity of India’s rich history and culture. This splendid volume also serves as a role model for the multidisciplinary studies of urban cultural landscapes in South Asia and beyond.

Buy the book.

P.K. Das, Mumbai

P.K. Das, Mumbai

Ecology and Equity: The Use and Abuse of Nature in Contemporary India

by Madhav Gadgil and Ramachandra Guha

1995, Routledge

It is a must read, published by Penguin Books India, but before that by Routledge in 1995. Over the years, I have read parts of this book several times and have extensively quoted it in my talks and writings.

Buy the book.

Samarth Das, Mumbai

Samarth Das, Mumbai

Housing Without Houses: Participation, Flexibility, Enablement

by Nabeel Hamdi

1995, Practical Action

Hamdi focuses on participatory planning as an essential component of sustainable development, with local communities at the forefront leading discussions and contributing to the production of neighborhoods in cities. The failures of the state and market forces to provide housing have been demonstrated in numerous cases, and the book discusses how architects and designers along with citizens are responsible for building just cities. Hyper-local knowledge of local citizens is an incredible resource that architects can tap while making their cases for production of neighborhoods. The book also emphasizes how local bodies need to work in unison with state powers to promote equitable development, with a balance of new production and preservation of cultural aspects of daily living. The traditional roles of architects need to be challenged and evolved in order to develop strategies for development from the ground up in today’s context. This is a must read for all!

Buy the book.

Marcelo de Souza, Rio de Janeiro

Marcelo de Souza, Rio de Janeiro

From Urbanization to Cities

by Murray Bookchin

Revised ed. 1996, Cassel & Co.

I think his reflections on cities and urbanization deserve much more attention that has been devoted to them so far. A few reasons:

1) Bookchin pioneered the analysis of urban ecology and political ecology from a critical viewpoint. His book Our Synthetic Environment (published under the penname “Lewis Herber”) was published a couple of months before Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring; probably due to the fact that his analysis is much more radical, Rachel’s book turned into a bestseller, while Bookchin’s book not…

2) Bookchin’s books The Limits of the City (1974), Post-Scarcity Anarchism (essays written between the mid-1960s and early 1970s) and, above all, Urbanization without Cities (1992) are as important or even more important than Lefebvre’s The Right to the City and The Urban Revolution—but everyone talks only about Lefebvre, who was in some regards not as profound or original as Bookchin.

3) Bookchin’s “social ecology” is a very important framework for the type of analysis we need in the 21st century.

Buy the book.

Anna Dietzsch, São Paulo

Anna Dietzsch, São Paulo

The Death and Life of Great American Cities

by Jane Jacobs

1961, Random House

The classic. Because it is the mother of everything we think is good for cities now: walking, meeting people, being diverse.

And worth re-reading, because it has been so much quoted and talked about, some of the ideas and principles have been kind of distorted.

Buy the book.

Paul Downton, Melbourne

Paul Downton, Melbourne

Ecocity Berkeley: Building Cities for a Healthy Future

by Richard Register

1987, North Atlantic Books

The first book with “ecocity” in its title and perhaps the key text of the ecocity movement, this slim volume describes a vision of Berkeley (but it could be any city) as a place of wildness and life, dense with vegetation and people but empty of cars, with a narrative propelled by exuberant enthusiasm and a kind of wild-eyed joy that is rare in city literature. From buildings covered with trees and vegetation to precarious glass-bottomed walkways, recovered creeks, and cars converted into planter boxes, this is the book that let loose many of the memes that now populate city disourse and urban design. Neither conventionally academic nor stiflingly professional, Ecocity Berkeley is richly illustrated with naive and quirky drawings that help communicate sublime and sophisticated ideas about fitting a city within the full embrace of nature—read it alongside Murray Bookchin’s Limits of the City for a radical social and political analysis of urbanisation and the incomparable Lewis Mumford’s City in History for a comprehensive overview of cities that, like Ecocity Berkeley, remain absolutely pertinent to understanding that we cannot make a healthy future without balancing our cities with nature.

Buy the book.

Katerina Elias, São Paulo

Katerina Elias, São Paulo

Cities for a Small Planet

by Richard Rogers

1998, Basic Books

In this book, Richard Rogers speaks to everyone: no matter the reader’s level of experience in urbanism and architecture, Roger reels in his readers, who in exchange are taken on a journey through the history of urbanism, urban decay, ecological design, and ultimately, humanity. This book is a potential classic in urban literature, and a fantastic entry point for beginners, or a recap for specialists, to contemplate the role of our cities and their potential for being a driving force for greater sustainability.

Buy the book.

Thomas Elmqvist, Stockholm

Thomas Elmqvist, Stockholm

Global Cities: A Short History

by Greg Clark

2016, Brookings Institution Press

The book gives a very interesting overview of past waves of globalisation events and the formation of city networks going back 4,000 years, up to the patterns and processes underlying today’s globalisation and formation of large city networks.

The book ends with an analysis and discussion of the globalisation and cities of the future. Although there are vast differences between the networks of cities along the ancient Silk Roads and the 21st-century system of global value chains and competitive advantage, there are also striking parallels. The author argues that the leaders of today’s cities can learn much from how those in previous waves built and sustained their competitive attributes, and how to avoid becoming locked into unsustainable or unproductive cycles of development.

Buy the book.

Jayne Engle, Montreal

Jayne Engle, Montreal

Sharing Cities: A Case for Truly Smart and Sustainable Cities

by Duncan McLaren and Julian Agyeman

2015, MIT Press

Everyone should read this book because it makes a case that the guiding purpose of the future city should be understanding the whole city as shared space, and acting to share it fairly. It brings together the notion of the city as a commons with a critical perspective on the sharing economy. Its compelling theory and a rich mix of city cases move the conventional smart city discourse from multinational companies driving city change, to technological innovation in the service of social innovation and well being for all urban dwellers.

Buy the book.

Ana Faggi, Buenos Aires

Ana Faggi, Buenos Aires

Cities for People

by Jan Gehl

2010, Island Press

Very easy to read for everyone, this book shows how real urban life takes place in the streets. A livable city is one that considers the human dimension and offers a friendly and safe environment. The book, available in English and in Spanish, gives many useful recommendations for planning and management.

Buy the book.

Martha Fajardo, Bogota

Martha Fajardo, Bogota

Design With Nature

by Ian McHarg

1969, Natural History Press

Written in the 60s, it could be seen as very outdated—most of the ideologies are largely realized and the methods are practiced. However, it is still relevant for anyone who is interested in humans’ relationship with nature and how can we improve it.

Buy the book.

Emilio Fantin, Bologna

Emilio Fantin, Bologna

L’anima dei luoghi: conversazione con Carlo Truppi

by James Hillman

RCS, Milano

L’anima dei luoghi (The Soul of the Place) is the transcript of a dialogue between the psychologist James Hilmann and the architect Carlo Truppi; it is aimed at understanding the profound identity between culture and nature. The nature of the place is rediscovered as a new subject of reference that has to establish new relations of meaning and to change human perceptions. To respect a “territory” by protecting it ecologically, instead of destroying it, means allowing its energy to live, to survive over time, and to come down to us. Hilmann’s perspective shows us how geographic coordinates can be seen as an expression of the soul of the place, and it also explains how in the same place, churches of different religions, and villages and cities of different ethnicities and culture, have given rise to a stratification of signs and memories. The book has not been translated to English.

Buy the book.

Ben Feldman, Los Angeles

Ben Feldman, Los Angeles

Last Child in the Woods: Saving our Children from Nature Deficit Disorder

by Richard Louv

2008, Algonquin Books

As a landscape architect, father of a four-year-old and uncle of two autistic nephews, reading the book further clarified a personal cause of purpose to make a case for creating meaningful places to expose children to nature in its many forms.

Buy the book.

Sheila Foster, New York

Sheila Foster, New York

Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier

by Edward Glaeser

2011, Penguin Books

It is a well-written, comprehensive paean to cities of all kinds across the world. It is also full of insights and policy prescriptions which, whether one agrees with them or not (and there is much I disagree with), challenges assumptions about how and why some cities succeed and others falter. A terrific read for our urban era in which cities will play an outsized role in economic life, politics, and culture.

Buy the book.

Niki Frantzeskaki, Rotterdam

Niki Frantzeskaki, Rotterdam

Greening the Red Zone

by Keith Tidball and Marianne Krasny

2013, Springer

I love this book. It shows how communities can take up greening actions as a means to regenerate their areas and reconnect communities with the past and the future. With case studies around the globe in cities that experience devastation because of natural disasters or wars and conflict, the book shows how nature in cities can restore identity and reignite hope for the future.

Buy the book.

David Goode, Bath

David Goode, Bath

Swifts in a Tower

by David Lack

1956, Methuen

Everyone dealing with the ecology of cities should read this, wherever you are in the world. David Lack was a great ecologist and a great writer who produced a wonderful story about the swift, explaining the intricacies of its life in amazing detail and especially its adaptation to city life. His book is a classic in the literature of urban ecology. We all need to understand the detailed workings of urban ecology; there are so many mysteries. This book provides a way into that world that you won’t forget, and you will certainly look at swifts with new eyes.

Buy the book.

Divya Gopal, Berlin

Divya Gopal, Berlin

Nature in the City: Bengaluru in the Past, Present, and Future

by Harini Nagendra

2016, Oxford University Press

The book is a good mix of research findings and narratives from locals about urban nature in an Indian city. It helps the reader to understand the various factors (colonial past, economics, poverty, development, etc.) that play a role in “what” and “how” urban nature is in the Indian sub-continent, and perhaps is applicable to many other cities in developing countries.

Buy the book.

Andrew Grant, Bath

Andrew Grant, Bath

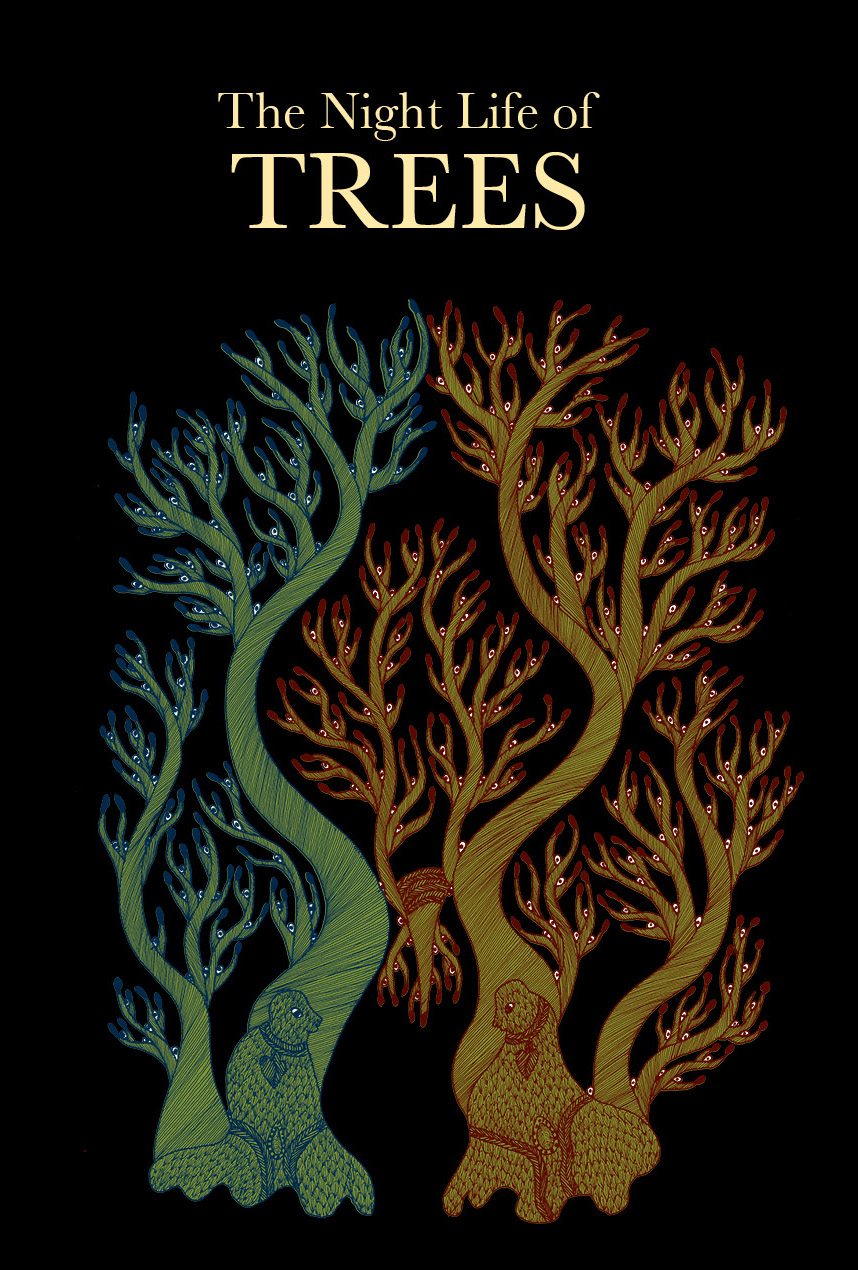

The Night Life of Trees

by Durga Bai, Bhajju Shyam, and Ram Singh Urveti

2006, Tara Books

This is a hand printed, illustrated book that I turn to when thinking about trees in cities. It captures the luminous spirits of trees at night, as portrayed by the Gond tribe in central India, and communicates the intimate relationship between the people and the forest that goes well beyond simple functional dependency into a way of life and thought. It is a visual reference for how we can relink our imagination and culture with urban nature.

Buy the book.

Bram Gunther, New York

Bram Gunther, New York

Baltimore School of Urban Ecology: Space, Scale, and Time for the Study of Cities

by J. Morgan Grove, Mary Cadenasso, Steward T. Pickett, Gary E. Machlis, William R. Burch Jr., Laura A. Ogden

2015, Yale University Press

A great story about an early and pioneering long-term ecology study city and how the study team blended social and ecological attributes to more deeply understand urban systems. Well written and speaks to all of us working in this arena.

Buy the book.

Jon Halfon, New York

This Changes Everything

This Changes Everything

by Naomi Klein

2014, Simon & Schuster

It might be a little too politically orientated for the list (although it shouldn’t be), but it does a fantastic job looking at the political and economic structures that are impeding large scale actions to address climate change. A little light on concrete solutions, but some worthwhile examinations on the roles of community organizing, protection of indigenous rights, and natural disaster recovery as the catalysts for system wide change.

Buy the book.

Fadi Hamdan, Beirut

Fadi Hamdan, Beirut

Al Muqaddimah

By Ibn Khaldoun

1377

In particular, Chapter 4. Some modern thinkers view it as the first work dealing with the philosophy of history or the social sciences of sociology, regarding the evolution of cities. It is an attempt at critical thinking in 1377 AD; unfortunately, that AD-thinking is much needed in 2016 in our Middle East region, and perhaps even beyond. Of course, much of what it says is now not applicable, but the critical thinking methodology is remarkable for its time. Buy the book.

Zoé Hamstead, Buffalo

Zoé Hamstead, Buffalo

The Manhattan Project: Theory of a City

by David Kishik

2015, Stanford University Press

This book is the elaboration of a “hypothesis” that Walter Benjamin did not commit suicide at Portbou, but in fact faked his own suicide and successfully fled Nazi Germany. In the book, The Manhattan Project is his manuscript, discovered in the NY Public Library (after his actual death), which articulates a theory of a place and the ways in which the form of the city shapes us in situated ways. New York is seen as an urban implosion, deriving its power from increased density and diversity—the economic, artistic, environmental, and equity dimensions of this urbanist movement are explored in relation to works and worldviews of Mumford, Jacobs, Arendt, and a slew of other important thinkers. It is a playful and thought-provoking work that experiments with place-based, fictional philosophy in the urban context.

Buy the book.

Mathieu Hélie, Montreal

Mathieu Hélie, Montreal

Delirious New York, A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan

by Rem Koolhaas

1997, The Monacelli Press

The concept of a retroactive manifesto is a paradigmatic stepping stone from the design stance of city planning to the ecological, emergent stance we need to embrace for urbanism to succeed as a science and practice.

Buy the book.

Tom Henfrey, Bristol

Tom Henfrey, Bristol

The Oregon Experiment

by Christopher Alexander

1975, Oxford University Press

Christoper Alexander’s “Pattern Language” trilogy sets out a compelling vision and agenda for a new participatory approach to architecture and urban design, where planning and settlement act as ongoing generative processes that reflect the deepest creative impulses of the universe itself. Of the three books, The Oregon Experiment is the most compact, and situates the philosophy set out in The Timeless Way of Building and methodology of A Pattern Language within the context of implementation of a real-world case study. Buy the book.

Cecilia Herzog, Rio de Janeiro

Cecilia Herzog, Rio de Janeiro

The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design

by Anne Spirn

1984, Basic Books

The book that made me look at cities in a totally new way is Anne W. Spirn’s The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design. It goes deep on how landscape interventions can impact the quality of the urban environment for better or worse. It even predicts what is happening now in many cities around the world.

Buy the book.

Mark Hostetler, Gainesville

Mark Hostetler, Gainesville

Sustainable Landscape Construction: A Guide to Green Building Outdoors

by J. William Thompson and Kim Sorvig

2007, Island Press

This book is important because the best design can fail if it is not implemented properly during the construction phase. For example, heritage trees that are marked for conservation in a subdivision development can subsequently die if heavy earthwork machines run over the root zone during construction.

Buy the book.

Mike Houck, Portland

Mike Houck, Portland

The Last Landscape

by William H. Whyte

1970, Doubleday Anchor

Everyone, but particularly those working on park open space (I hate that term), and planning issues (regional especially) should read this old, but never more relevant, book. A comprehensive, holistic rationale for integrating nature into the city and natural resource planning across the urban and rural (regional) landscape. Inspires me today as much as on my first reading 35 years ago.

Buy the book.

Todd Lester, São Paulo

Todd Lester, São Paulo

The Practice of Everyday Life

by Michel de Certeau

1984, University of California Press

…and specifically the chapter on “Walking in the City” in which he offers an “operational concept” that attempts to subordinate urban growth to user needs. While one of the primary references for his 1984 work—the World Trade Center—no longer exists and has certainly been surpassed in terms of largesse, de Certeau reaches ahead and amply problematizes extreme edifice for cities “founded by utopian and urbanistic discourse.” He reminds of the “tactics” required to navigate the contemporary city, and equally reaches back to LeFebvre’s “demand [for] a transformed and renewed access to urban life.”

Buy the book.

Nina-Marie Lister, Toronto

Nina-Marie Lister, Toronto

The Culture of Nature: The North American Landscape from Disney to the Exxon Valdez

by Alexander Wilson

1991, Between the Lines Press

The late Alexander Wilson (a Canadian landscape designer and cultural critic) pre-dates Cronon in exploring the hierarchical dualisms that underlie our perceptions of nature in an urbanizing world. Wilson asserts that the environmental crisis is a cultural crisis, beyond the confines of landscape, which itself is full of deeply conflicting ideas about the natural world—and these are manifest most powerfully in our cities and suburbs. (For those who can’t access this out-of-print Canadian volume, you might go to David Orr’s [2002] The Nature of Design: Ecology, Culture, and Human Intention [Oxford Press] for related reasons, but that would be a second recommendation, so…. there.)

Buy the book.

Shuaib Lwasa, Kampala

Shuaib Lwasa, Kampala

Urban Environments in Africa: A Critical Analysis of Environmental Politics

by Garth Myers

2016, University of Chicago Press

This book analyses power and resultant cityscapes through the Situated Urban Political Ecology lenses. Drawing on various examples from Africa, it reflects on how power shapes urban environments, leading to different configurations. Myers argues that urban African environments go beyond just power versus counter power to a structure of feeling—that assessing urban physical environments merely as sites of risks misses seeing these cities as wellsprings of environmental opportunities.

Buy the book.

Patrick Lydon, Seoul

Patrick Lydon, Seoul

Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered

by E.F. Schumacher

1973, Harper & Row

An economic text for those in search of an economy that works for people and the environment, Schumacher’s treatise has been called one of the most influential books published in the past century. Based in the kind of socially and ecologically connected thinking where the well-being of people and cities sprouts from something more basic than sheer economic and industrial growth, the writing offers invaluable philosophical and practical wisdom for those looking to achieve the trifecta of social, economic, and ecological sustainability. Regardless of the discipline, every successful sustainability plan is bound to find its roots tucked somewhere in the theories of Small is Beautiful.

Buy the book.

Yvonne Lynch, Melbourne

Yvonne Lynch, Melbourne

The City and the Coming Climate

by Brian Stone Jr.

2012, Cambridge University Press

Climate change will fundamentally challenge the way we design, build, and manage our cities. In this book, Stone explains the pertinent climate science and articulates the profound impact of climate change and urban heating, which are currently affecting our cities. He puts forth a range of interventions that can be considered for adapting our cities and building resilience in a positive manner.

Buy the book.

Ian MacGregor-Fors, Xalapa

Ian MacGregor-Fors, Xalapa

Concrete Jungle: New York City and Our Last Best Hope for a Sustainable Future

by Niles Eldredge & Sidney Horenstein

2014, University of California Press

This book is a walk-through of New York City, from the geological origin of the land on which it sprawls to the current social-environmental actions that are being considered to tackle the city’s issues. Although the book focuses on NYC, much of its content applies to large cities around the globe. It is very well written, mostly for a general audience, and provides fantastic details.

Buy the book.

Mahim Maher, Karachi

Mahim Maher, Karachi

Karachi: Ordered Disorder and the Struggle for the City

Laurent Gayer

2014, OUP & Hurst

We were lucky, oh so lucky, to have Laurent Gayer explode onto the scene in 2014. Laurent works at Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in France, but came to Karachi for several years to do this book, after having learnt Urdu in India. I believe his ability to conduct his interviews in Urdu, often shocking his unsuspecting subject, was the secret to the success of this granular examination of the forces that shape Karachi. Karachi has a rep for being the most violent city in the world (never mind that Oakland and Ciudad Juarez also once had a higher homicide rate). The violence was inexplicable; sure, experts had their theories, but none of them satisfied me. (I was working as the head of the metropolitan pages during some of its most violent years). What Laurent has done is explain “us”. His brilliant theory is “ordered disorder” or managed chaos. He explains why Karachi continues to function while falling apart every day. Best of all, it is a riveting read because he approaches it almost like a journalist and tells the story. Ordered Disorder is essential reading also for anyone who wants to understand the history of modern Karachi, how certain factors have influenced its growth, decay, and resilience, and how we often work “through” violence.

Buy the book.

Jala Makhzoumi, Beirut

Jala Makhzoumi, Beirut

Damascus City: A Study in Urban Geography

by Safouh Khair

1982, Ministry of Culture Publications, Damascus

In Arabic, a holistic narrative of natural and cultural processes that shaped urban morphology. The book is a must to understand evolution of the three components that shaped the morphology, architecture, and cultural landscape of this ancient oasis city.

François Mancebo, Paris

François Mancebo, Paris

The Right to the City

by Henri Lefebvre

(in French, Le droit à la Ville)

1968, Peninsula

Let’s turn to the great classics. The Right to the City is a touchstone for people working on social production of space and justice in the city. Some, like Susan Feinstein, consider that The Right to the City is more a rhetorical device than a policy-making tool. Still, this book, published in 1968, has inspired countless academic authors and practitioners in urban planning and urban design up through today.

Buy the book.

E.J. McAdams, New York

E.J. McAdams, New York

City Eclogue

by Ed Roberson

2006, Atelos

One of the few American poets with field experience in biology, Ed Roberson brings his innovative poetic forms and radical imagination to singing the ecological, political, and racial ecosystems of the city. If The Nature of Cities community is going to read one poetry book in 2017, this is it!

Buy the book.

Rob McDonald, Washington

Rob McDonald, Washington

City Trees: A Historical Geography from the Renaissance through the 19th Century

by Henry Lawrence

2008, University of Virginia Press

What is mind-blowing in this book is the painstaking reconstruction of tree cover and parks in major cities from the 16th century on. It really changes your perspective to learn, for instance, that the Dutch practice of having trees along canals spread to trees along streets in Amsterdam, and that the initial response of most observers from other countries was bewilderment (why in the world would you want trees in a city?!). The book provides the detailed historical evidence that how we have tried to use nature in cities has changed and expanded multiple times since the renaissance, and (optimistically) could expand again even in our current urban century.

Buy the book.

Brian McGrath, Newark

Brian McGrath, Newark

Nature’s Metropolis:

Chicago and the Great West

by William Cronon

1992, W. W. Norton & Company

For me, an architect, Nature’s Metropolis helped me see cities in a much more complex way.

Buy the book.

Timon McPhearson, New York

Timon McPhearson, New York

Concrete and Clay: Reworking Nature in New York City

by Matthew Gandy

2002, MIT Press

Concrete and Clay wonderfully traces the development of New York City and the shifting and contrasting views within key development projects integrate a “metropolitan nature” in the city and the region. The focus on capital and political power in decision-making and the impact this has on urban environments is a useful history that remains important as a story about the impacts of urban development on all nature in the context of an urbanizing planet.

Buy the book.

Hitesh Mehta, Miami

Hitesh Mehta, Miami

Life between Buildings: Using Pubic Space

by Jan Gehl

1980, John Wiley & Sons

A must-have for any library shelf on city planning. First published in 1980, it was both enlightening and thoughtful, and even then asked the fundamental question “What has happened to life in cities?”. The book has had a lasting influence on the quality of public open spaces and has especially helped architects and urban planners better understand the larger public life of cities. Focused on how humans use public spaces, Gehl places substance and quantitative research behind urban planning.

Buy the book.

Patrice Milillo, Los Angeles

Patrice Milillo, Los Angeles

The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community, and Everyday Life

by Richard Florida

2002, Basic Books

This book explains how important placemaking is and the economic power wielded by creativity.

Buy the book.

Mary Miss, New York

Mary Miss, New York

The Great Derangement

by Amitav Ghosh

2016, University of Chicago Press

I really enjoyed this book because of the way Ghosh makes clear the important role of “culture” in thinking about the climate crisis, whether it’s the role the writer / artist has in making such a topic central to our thinking about the world or the way our “political culture” has brought us to this point. Ghosh writes with great insight and allows us to track these links in a very compelling way.

Buy the book.

Franco Montalto, Philadelphia

Franco Montalto, Philadelphia

Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things

by William McDonough and Michael Braggart

2002, North Point Press

I have found Cradle to Cradle seminal in my development. It makes the critically important distinction between eco-effective and eco-efficient design. The former is a radical departure from how we’ve made things for most of the industrial history of the world. The latter is simply a slower way of destroying the world. I believe this book is of interest to all involved in the design process, regardless of scale.

Buy the book.

Polly Moseley, Liverpool

Polly Moseley, Liverpool

The Growing Stone

by Albert Camus

1957

In French, La pierre qui pousse. A short story, this is brilliant in terms of a story of myth blending with city engineering. It’s about inequalities, about myth-making, about changing the narrative of a town in a deeply democratic way. When I read it a centenary on from Camus’ birth, it blew my mind.

Buy the book.

,

Harini Nagendra, Bangalore

Harini Nagendra, Bangalore

Landscapes of Urban Memory: The Sacred and the Civic in India’s High-Tech City

by Smriti Srinivas

2001, University of Minnesota Press and Orient Longman

My book is set in the southern hemisphere, a fascinating account of how traditional and modern cultures, ecologies, and visualisations of the sacred and the civic influence each other, in the backdrop of the globalising city of Bangalore. It focuses on an iconic sacred event, the annual Karaga performance. Conducted by a traditional community of gardeners, the Karaga is organised around a network of garden and lake sites. Many of these sites have now vanished from the city, but survive vividly in memory and imagination, while others are still physically extant, though substantially altered in form and function. Through the lens of the Karaga, Smriti Srinivas describes the complex, changing matrix of cultural, political, and social ties to nature in an Indian city where tradition and modernity are two sides of the same coin. The book provides a scholarly insight into social transformations in a modern Indian city, but at the same time takes you deep into the lives and imagination of people in the city, describing how they see and value nature, and how this has changed over time. It’s one of my favorite books, on my favorite city. Happy reading!

Buy the book.

Kate Orff, New York

Kate Orff, New York

Great Expectations

by Charles Dickens

1860

A novel that traces how cities began forming the modern backdrop for humanity and a portrait of the multiple human stories and twists of fate (luck, cruelty, love) that cities foster.

Buy the book.

Susan Parnell, Cape Town

Susan Parnell, Cape Town

New Babylon New Nineveh: Everyday Life on the Witwatersrand, 1886-1914

By Charles Van Onselen

2011, Jonathan Ball Publishers

I love Gwendoline Wright’s volume on the Politics of Urban Design in French Colonial Urbanism because it’s the South speaking back to the North—but the “urban” book that really got me hooked on doing city research and convinced me, as a geographer, that there was a real value in a historical perspective, is Olsen’s two-volume set of essays about Johannesburg. Beautifully written, place and people sensitive—but with a much bigger understanding of political economy.

Buy the book.

Raquel Peñalosa, Montreal

Raquel Peñalosa, Montreal

The Death and Life of Great American Cities

by Jane Jacobs

1961, Random House

Because of its intemporality, it is always inspiring to new generations—to transform the City, and mostly its people. It remains fresh and pertinent in its transversality, dealing with social, urban, human, gender, and generational issues in a simple and engaged manner.

Buy the book.

Steward Pickett, Poughkeepsie

Steward Pickett, Poughkeepsie

The Granite Garden

by Anne Spirn

1984, Basic Books

Anne is one of the pioneers and continuing deep thinkers about the relationship of ecological, geological, and climatic processes and context that interact with urban design. Her approach is based on data and knowledge, yet informs the creative and human-centered intentionality of urban design. Her writing is a joy to read, and her insights are still fresh today.

Buy the book.

Stephanie Pincetl, Los Angeles

Stephanie Pincetl, Los Angeles

Architecture Without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture

by Bernard Rudofsky

1965, The Museum of Modern Art

It shows the wisdom and creativity of builders who did not have a formal education, but were observant and inventive. The traditional forms and materials both came from local places and were built to shelter from heat and cold and to take advantage of natural phenomena such as wind and sun to create livable cities and communities. The end results were cities and villages that addressed local conditions for thermal and human well-being.

Buy the book.

Christine Platt, Durban

Christine Platt, Durban

Arrival City

by Doug Sanders

2011, Windmill Books

It is a remarkable book telling the story of what happens to people arriving in a series of world cities. It explains how they have adapted to the barriers that face them and gives us a much keener understanding of just why the peripheral—or arrival—places in our cities are the way they are. It covers cities in countries as far flung as China, Iran, and France.

Buy the book.

Andrew Revkin, New York

Andrew Revkin, New York

The Well-Tempered City

by Jonathan F.P. Rose

2016, Harper Collins

It’s a welcome summary of studies and cases showing that the social and cultural infrastructure of cities can be as important as the physical infrastructure.

Buy the book.

Debra Roberts, Durban

Debra Roberts, Durban

Design with Nature

by Ian McHarg

1969, Natural History Press

This was one of the first “how to” books addressing nature and cities. Instead of just theorizing about the city and how it might be changed, McHarg offered a practical approach to urban design that allowed the incorporation of nature into city plans. His “overlay” thinking paved the way for subsequent GIS based planning approaches, without which it would be impossible to protect nature and biodiversity in the 21st Century city.

Buy the book.

Eric Sanderson, New York

Eric Sanderson, New York

Carfree Cities

by J.H. Crawford

2002, International Books

Little known but much loved by those who have had the pleasure of reading it, J.H. Crawford’s book, Carfree Cities, walks through every aspect of what it would be like to live in a town or city without cars. Thoughtful and surprising, this short book will remind you of Christopher Alexander’s Pattern Language, Jan Gehl’s devotion to livable cities, and Richard Perl’s systemic understanding of how transportation shapes urban form, all before Google’s Self-Driving Car or Uber were on the horizon. Illustrated by Arin Verner.

Buy the book.

Jason Schupbach, Washington

Jason Schupbach, Washington

The Image of the City

By Kevin Lynch

1960, MIT Press

An absolute essential, in this short book, Lynch revolutionized the way city planners thought about how people move through and view their cities. The basic lessons of what elements a well-designed city has are all here. It will shift your thinking of how residents of a place conceive of their city, and change the way you look at a city yourself.

Buy the book.

Richard Scott, Liverpool

Richard Scott, Liverpool

Cities for People

by Jan Gehl

2010, Island Press

Considering cities through five human senses is a good place to describe how we react to the spaces around us, and how best to respond to them. It’s a great starting point for planning better cities.

Buy the book.

Paula Segal, New York

Paula Segal, New York

Invisible Cities

by Italo Calvino

1972, Harcourt Brace & Company

Invisible Cities, for understanding that cities themselves are organisms that run on empathy.

Always good to re-read to remember that everything we build or reconstruct will be seen with many, many different eyes and be part of many, many different stories.

Buy the book.

Huda Shaka, Dubai

Huda Shaka, Dubai

Dubai Amplified: The Engineering of a Port Geography

by Stephen Ramos

2010, Routledge

While Dubai has received some attention from architects and planners recently, the literature on it has been somewhat superficial. This book considers the evolution of the city over the past 50 years and links it to major infrastructure development, an often over-looked aspect. The city of “glam” is actually a city of “ports”. The book provides insights into the politics and economics of development in the Arabian Gulf.

Buy the book.

Laura Shillington, Managua & Montreal

Laura Shillington, Managua & Montreal

The City & The City

by China Miéville

2003, Penguin/Random House

The fundamental idea in The City & The City is that two different cities occupy the exact same geographical site. The spaces in the cities overlap, but they are legally separate entities. The cities in the book symbolise the ways in which there are multiple and diverse spaces in real cities, but how certain spaces (and the people who produce and occupy them) are “othered”.

Buy the book.

Philip Silva, New York

Philip Silva, New York

Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature

Edited by William Cronon

1996, W. W. Norton & Company

Nature’s Metropolis (1992), Cronon’s history of Chicago and its Western hinterland, would probably be a more obvious fit for this list. Yet Uncommon Ground is a primer for deconstructing many widely held misconceptions about the relationship between humans and nature, including the place of cities in an environmentally enlightened society. The introduction alone should be required reading for any student of cities and the environment.

Buy the book.

David Simon, Gothenburg

David Simon, Gothenburg

Designing Public Policy for Co-production: Theory, practice and change

Edited by Catherine Durose and Liz Richardson

2016, Policy Press

This is arguably the best guide to the shortcomings of conventional public policymaking and the potential of co-production methodologies. The diverse authors, a mix of academics and practitioners based in the U.K. and U.S.A., draw on long experience at the (mainly urban) public policy-practice interface to explore the potentials and challenges of experience with diverse forms of transdisciplinary co-design or co-production.

Buy the book.

Kevin Sloan, Dallas/Fort Worth

Kevin Sloan, Dallas/Fort Worth

The Matrix of Man: Illustrated History of Urban Environment

by Sibyl Moholy-Nagy

1968, Pall Mall Press

Every time I open The Matrix of Man: Illustrated History of Urban Environment by Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, I learn something important.

This is a book that contains an inventory of urban models as well as speculations on the contemporary city as it was imagined in the 20th century. While recent texts discuss mega-cities as they have unfolded, this book was published as they began to appear.

Beautifully and intelligently written, the book’s author, Moholy-Nagy, was the wife of a Lazlo Moholy Nagy, a seminal figure in the early 20th century who also taught at the Bauhaus.

Buy the book.

Laura Spinadel, Vienna

Laura Spinadel, Vienna

Campus WU: A Holistic History

by Ila Berman

2013, BOA buero fuer offensive aleatorik

Unlike the global village, which in its attempt to homogenize is increasingly exclusive, we understand that holistic villages, like the Campus WU, are the places that celebrate diversity and inclusion. Our actions can give form to holistic societies. That is our hope and a dream we want to share with all those who we meet along our way and which on the Campus WU was the common denominator and the holistic fire that united us before the proposed challenge. And so it was that on the back cover of the book Campus WU: A Holistic History, I wrote: “It is about the making of places that seek a dialogue with creation, with the hope of encouraging the people who experience our spaces to unconsciously perceive them. The reality is showing me that something magical happened in Vienna and that thousands of people allow themselves to be seduced by this utopia that became reality.”

David Tittle, Chatham

David Tittle, Chatham

Cities in Civilisation

by Peter Hall

1998, Pantheon

Professor Hall brings together a lifetime of scholarship on the nature and functioning of cities to weave an extraordinary story of economics, politics, anthropology, and culture across millennia and continents. It is a huge tome, but at the same time is enjoyably readable and a great resource for understanding the city’s role in the history of our species, and the complex combination of factors that make for great cities.

Buy the book.

Anne Trumble, Los Angeles

Anne Trumble, Los Angeles

Imagining Extinction: The Cultural Meanings of Endangered Species

by Ursula K. Heise

2016, University of Chicago Press

Heise effectively argues why any advocacy on behalf of endangered species must understand the cultural frameworks that shape what we think is and isn’t valuable in nature. As Heise illustrates in her twisting and turning narrative through the diverse ways humans make cultural assumptions about nature, conflicts and convergences of these things in the Anthropocene open up a new vision of multi-species justice. Imagining Extinction makes it clear that cities are ground zero for this vision.

Buy the book

Naomi Tsur, Jerusalem

Naomi Tsur, Jerusalem

If Mayors Ruled The World: Dysfunctional Nations, Rising Cities

by Benjamin Barber

2013, Yale University Press

Why? Because it addresses boldly, if impractically, the total dysfunctionality of the global division of the world into so-called nations. In an increasingly urban world, the reins of management will be more effective in the hands of cities, especially if their jurisdiction takes in their entire bio-shed. In a world ruled by cities, we can hopefully talk more about urbanism, nature, sewage, garbage, transportation, education, health, prosperity, and cultural diversity—and less about war and peace…

Buy the book.

Chantal van Ham, Brussels

Chantal van Ham, Brussels

Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning

by Timothy Beatley

2010, Island Press

I would recommend urban planners to read Timothy Beatley’s Biophilic Cities; it is such a great way to think about what nature means for all of us and especially those who live in cities, and how it can benefit urban citizens in every part of the world.

Buy the book.

Shawn Van Sluys, Guelph

Shawn Van Sluys, Guelph

The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination

by Sarah Schulman

2013, University of California Press

In The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination, which Mike Young reviewed for ArtsEverywhere.ca, Sarah Schulman shows how the gentrification of many neighbourhoods in New York during and after the AIDS crisis correlates to the forgotten politics and socialities of queerness as it intersects with racial and economic struggles. The gentrification of space is the gentrification of the mind through the erasure of histories, relationships, rights, and differences.

Buy the book.

Claire Weisz

Claire Weisz

The Fall of Public Man

by Richard Sennett

1977, W. W. Norton & Company

The book that made the first cultural argument about the loss of the civic commons that was the genesis of urbanity.

Also a great piece of writing.

Buy the book.

Mike Wells, Bath

Mike Wells, Bath

Green Design: From Theory to Practice

by Ken Yeang and Arthur Spector, eds.

2011, Blackdog Architecture

Yeang and Spector have been doing the green thing in cities—not just thinking about it—longer than almost anyone. This book is a temperature take on where we are and should be in delivery of green, sustainable, biodiverse cities in practice. It links across all or most design themes—not just addressing low or zero carbon, or water sensitive urban design, and stopping there, but making the point that the sustainable city has to be truly green, vegetated, biodiverse, and biophilic, too. Architects need ecologists to design good cities.

Buy the book.

Diana Wiesner, Bogotá

Diana Wiesner, Bogotá

Naturaleza Urbana. plataforma de experiencias

edited by María Angélica Mejía

2016, Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt

The Spanish version of the book can be downloaded here.

Es necesario contemplar las acciones concretas de la Ciudadanía respecto al cuestionamiento del papel de la naturaleza en la ciudad. Los gobiernos locales subestiman el poder de la acción ciudadana. Uno de los potenciales más poderosos es la capacidad que puede tener una complicidad público privada para una gestión efectiva de la biodiversidad en la transformación positiva de las ciudades. Este libro se logró gracias a la participación de más de 80 casos en diversos lugares de Colombia.

Kathleen Wolf, Seattle

Kathleen Wolf, Seattle

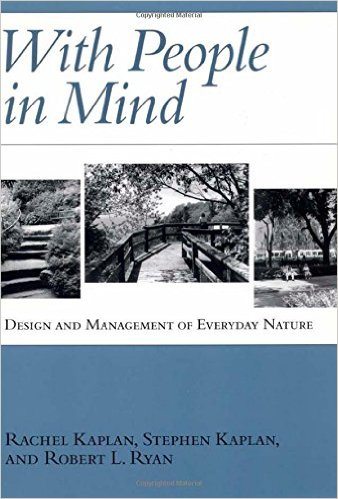

With People in Mind: Design and Management of Everyday Nature

by Rachel Kaplan, Stephen Kaplan and Robert L. Ryan

1998, Island Press

The book explores how to design and manage areas of “everyday nature” in ways that are beneficial to and appreciated by humans. The book translates many years of empirical studies into practical design and management approaches, and it is a readable and flexible guide for practitioners and managers in many fields. It takes theory and research evidence to small-scale changes that improve quality of life.

Buy the book.

Pippin Anderson, Cape Town

Pippin Anderson, Cape Town Gloria Aponte, Medellín

Gloria Aponte, Medellín Ana Luisa Artesi, Buenos Aires

Ana Luisa Artesi, Buenos Aires Xuemei Bai, Canberra

Xuemei Bai, Canberra Stephan Barthel, Stockholm

Stephan Barthel, Stockholm Jane Battersby, Cape Town

Jane Battersby, Cape Town Adrian Benepe, New York

Adrian Benepe, New York Genie Birch, Philadelphia & New York

Genie Birch, Philadelphia & New York Timothy Bonebrake, Hong Kong

Timothy Bonebrake, Hong Kong Eduardo Brondizio, Bloomington

Eduardo Brondizio, Bloomington Steve Brown, Sydney

Steve Brown, Sydney Lena Chan, Singapore

Lena Chan, Singapore Lindsay Campbell, New York

Lindsay Campbell, New York The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects

The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects Katrine Claassens, Cape Town

Katrine Claassens, Cape Town Bharat Dahiya, Bangkok

Bharat Dahiya, Bangkok P.K. Das, Mumbai

P.K. Das, Mumbai Samarth Das, Mumbai

Samarth Das, Mumbai Marcelo de Souza, Rio de Janeiro

Marcelo de Souza, Rio de Janeiro Paul Downton, Melbourne

Paul Downton, Melbourne Katerina Elias, São Paulo

Katerina Elias, São Paulo Thomas Elmqvist, Stockholm

Thomas Elmqvist, Stockholm Jayne Engle, Montreal

Jayne Engle, Montreal Ana Faggi, Buenos Aires

Ana Faggi, Buenos Aires Emilio Fantin, Bologna

Emilio Fantin, Bologna Ben Feldman, Los Angeles

Ben Feldman, Los Angeles Sheila Foster, New York

Sheila Foster, New York Niki Frantzeskaki, Rotterdam

Niki Frantzeskaki, Rotterdam David Goode, Bath

David Goode, Bath Divya Gopal, Berlin

Divya Gopal, Berlin Andrew Grant, Bath

Andrew Grant, Bath Bram Gunther, New York

Bram Gunther, New York This Changes Everything

This Changes Everything Fadi Hamdan, Beirut

Fadi Hamdan, Beirut Zoé Hamstead, Buffalo

Zoé Hamstead, Buffalo Mathieu Hélie, Montreal

Mathieu Hélie, Montreal Tom Henfrey, Bristol

Tom Henfrey, Bristol Cecilia Herzog, Rio de Janeiro

Cecilia Herzog, Rio de Janeiro Mark Hostetler, Gainesville

Mark Hostetler, Gainesville Mike Houck, Portland

Mike Houck, Portland Todd Lester, São Paulo

Todd Lester, São Paulo Nina-Marie Lister, Toronto

Nina-Marie Lister, Toronto Shuaib Lwasa, Kampala

Shuaib Lwasa, Kampala Patrick Lydon, Seoul

Patrick Lydon, Seoul Yvonne Lynch, Melbourne

Yvonne Lynch, Melbourne Ian MacGregor-Fors, Xalapa

Ian MacGregor-Fors, Xalapa Mahim Maher, Karachi

Mahim Maher, Karachi Jala Makhzoumi, Beirut

Jala Makhzoumi, Beirut François Mancebo, Paris

François Mancebo, Paris E.J. McAdams, New York

E.J. McAdams, New York Rob McDonald, Washington

Rob McDonald, Washington Brian McGrath, Newark

Brian McGrath, Newark Timon McPhearson, New York

Timon McPhearson, New York Hitesh Mehta, Miami

Hitesh Mehta, Miami Patrice Milillo, Los Angeles

Patrice Milillo, Los Angeles Mary Miss, New York

Mary Miss, New York Franco Montalto, Philadelphia

Franco Montalto, Philadelphia Polly Moseley, Liverpool

Polly Moseley, Liverpool Harini Nagendra, Bangalore

Harini Nagendra, Bangalore Kate Orff, New York

Kate Orff, New York Susan Parnell, Cape Town

Susan Parnell, Cape Town Stephanie Pincetl, Los Angeles

Stephanie Pincetl, Los Angeles Christine Platt, Durban

Christine Platt, Durban Andrew Revkin, New York

Andrew Revkin, New York Eric Sanderson, New York

Eric Sanderson, New York Jason Schupbach, Washington

Jason Schupbach, Washington Paula Segal, New York

Paula Segal, New York Huda Shaka, Dubai

Huda Shaka, Dubai Laura Shillington, Managua & Montreal

Laura Shillington, Managua & Montreal Philip Silva, New York

Philip Silva, New York David Simon, Gothenburg

David Simon, Gothenburg Kevin Sloan, Dallas/Fort Worth

Kevin Sloan, Dallas/Fort Worth Laura Spinadel, Vienna

Laura Spinadel, Vienna David Tittle, Chatham

David Tittle, Chatham Anne Trumble, Los Angeles

Anne Trumble, Los Angeles Naomi Tsur, Jerusalem

Naomi Tsur, Jerusalem Chantal van Ham, Brussels

Chantal van Ham, Brussels Shawn Van Sluys, Guelph

Shawn Van Sluys, Guelph Claire Weisz

Claire Weisz Mike Wells, Bath

Mike Wells, Bath Diana Wiesner, Bogotá

Diana Wiesner, Bogotá Kathleen Wolf, Seattle

Kathleen Wolf, Seattle

For those who already believe that efforts to restore ecological functions in urban systems are worthwhile, this book provides case studies that underscore the value of urban stream projects and some general principals of stream restoration design drawn from Riley’s own experience and others’. Practioners in the field of stream restoration will empathize with the missteps described at some sites, and the repeated lesson that trying to restore an urban stream means facing not only physical, but also economic, political, and social-cultural challenges.

For those who already believe that efforts to restore ecological functions in urban systems are worthwhile, this book provides case studies that underscore the value of urban stream projects and some general principals of stream restoration design drawn from Riley’s own experience and others’. Practioners in the field of stream restoration will empathize with the missteps described at some sites, and the repeated lesson that trying to restore an urban stream means facing not only physical, but also economic, political, and social-cultural challenges.

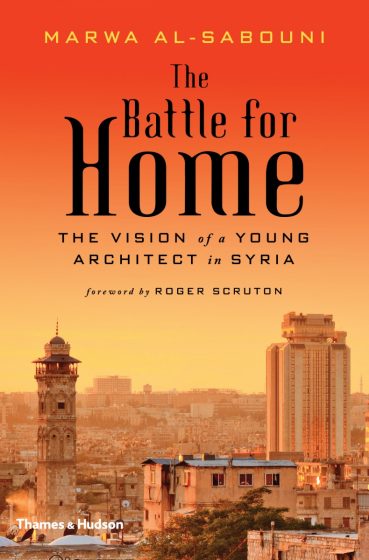

Al-Sabouni’s argument for paying attention to the relationship between city morphology, urbanism, and well-being is one that has been put forward before, but in thinking of nature in the nature of cities, we have not given this other relationship enough attention. It points directly to the relationship between the hard mineral surfaces humans construct, their form and layout, and the position and location of urban elements like parks or trees, or gardens and court yards: destinations, interwoven in daily pathways, privatized in yards, and so forth. Her argument for a generous city also resonates through housing: its accessibility, affordability, grace, and disposition on the landscape that can facilitate or encourage natural elements as well as amity among residents—in fact, those elements may be essential to the nurturing of civility and cordiality. The types of public spaces, their arrangements and relationship to buildings, are important, too, in making an open and inviting city. As Al-Sabouni writes of the old Homs where she grew up, “[T]he buildings, streets, and trees were not just the components of the urban environment; they were the very soul of the community, creating the faces we saw, the shops we bought from and the shape sound and feel of every footstep we took. In sum, such things shape our shared experience of belonging and the collective conscience of the city. . . . [to] make our coexistence into one existence” pg. 68 (italics in the original).

Al-Sabouni’s argument for paying attention to the relationship between city morphology, urbanism, and well-being is one that has been put forward before, but in thinking of nature in the nature of cities, we have not given this other relationship enough attention. It points directly to the relationship between the hard mineral surfaces humans construct, their form and layout, and the position and location of urban elements like parks or trees, or gardens and court yards: destinations, interwoven in daily pathways, privatized in yards, and so forth. Her argument for a generous city also resonates through housing: its accessibility, affordability, grace, and disposition on the landscape that can facilitate or encourage natural elements as well as amity among residents—in fact, those elements may be essential to the nurturing of civility and cordiality. The types of public spaces, their arrangements and relationship to buildings, are important, too, in making an open and inviting city. As Al-Sabouni writes of the old Homs where she grew up, “[T]he buildings, streets, and trees were not just the components of the urban environment; they were the very soul of the community, creating the faces we saw, the shops we bought from and the shape sound and feel of every footstep we took. In sum, such things shape our shared experience of belonging and the collective conscience of the city. . . . [to] make our coexistence into one existence” pg. 68 (italics in the original).

Smith and Kadinsky are not alone in being drawn to running water. Paul Talling’s

Smith and Kadinsky are not alone in being drawn to running water. Paul Talling’s

2 Comments

Join our conversation