Can an urban garden help us remember what it means to be human?

Three months ago, we opened a slightly audacious restaurant and garden in a working-class suburb of Osaka, Japan with the intent of connecting people more deeply with food and nature in their neighborhood. Experimental and temporary in nature, the project was approached not as a business or social enterprise, but as what might be called a “social practice” artwork.

When this restaurant opened for dinner, we seated guests and took their orders as most any restaurant would. Then we kindly let them know that their dinner would be ready to eat in six weeks, explaining that we would first have to grow it in the garden down the street.

The project was called “REALtimeFOOD: the world’s slowest restaurant” (http://www.finalstraw.org/our-worlds-slowest-restaurant-serves-dinner-finally/) and although we were met with a few seriously raised eyebrows, most of the participants left that first night with smiles on their faces, almost all of them returning six weeks later to eat what they had ordered.

When the dinner finally arrived six weeks later, guests were treated to a rice dish made by friend and macrobiotic chef Kaori Tsuji, topped with greens, radish, and a spicy mixture of eggplant, onion, cucumer, and herbs from the garden, similar to Korean ‘bibmbap’, if you are familiar with it.

My personal favorite, though, was the dessert, a cool tomato jelly with whipped soy cream, garnished with mint. Surprisingly refreshing and delicious.

So what was the point of making customers wait six weeks? And how did it help cultivate relationships between people and urban nature?

Cultivating compassion and relationships

Outside of the restaurant, most of the action happened during the weeks in between the ordering and serving of the food.

To grow the food, we built a garden in an unused dirt lot. This wasn’t a typical organic urban garden, however. It was based on the principal that our design and actions would be rooted in two key concepts 1) connection between people and nature and 2) compassion for all of nature. Whenever we had to make a decision about the direction, we referred back to this principal, asking ourselves: does it cultivate connection with nature, and does it build compassion for nature?

For those not familiar with how connection and compassion relate to a garden, this particular kind of garden takes its aim from the ‘natural farming’ tradition in Japan. No tilling, no weeding, no killing bugs, no externally produced fertilizers. Similar in action to permaculture or agroecological practices–which a recent U.N. study believes might be our only way to sustainably feed a growing population – natural farmers see themselves as equals with plants and the rest of the natural world. This relationship, and the compassion which comes from it, are the primary informants for every action in their farms.

This is important for us, especially in urban social settings where compassion is sorely needed, yet often difficult to teach and apply. The kind of compassion learned by an individual on a natural farm will travel with them into their lives outside the farm or garden. It permeates their relationships with other people (our social relationships begin mending themselves), with other living things (human relationships to animals and plants become stronger), and even with the built structures of the city (leading to the city being cared for by its inhabitants).

Not only, then, is urban natural farming an ecologically regenerative practice, but the positive social effects are immense as well.

Working with art in the garden

One great difficulty is how to impart such an impossibly idealistic sounding mindset to the urban dweller, how to build and disseminate a deep and complex educational framework across the broad and diverse demographic range found in major urban centers.

In reality, we often make it sound more complex than it is.

What we have found in practice is that although the framework—and a sincere understanding and dedication to that framework—is required, there is not so much difficult ‘instruction’ as one might think. The process of developing such a mindset is largely one of giving people the place and permission to find this mindset of compassion and connection for themselves.

In our little Osaka garden, tucked between half-century-old homes, warehouses, and small factories, we helped individuals cultivate relationships between themselves and the plants and living things in the soil. With these relationships in mind, they grew food and created artworks using natural materials, always with a base of connection and compassion in their actions.

Art making is a key for us here too, not only because it uses and reinforces myriad connections to the environment at its very root, but because it gives participants a personally expressive output and a record of their relationship with the soil, the plants, and the other natural living or growing things in their city.

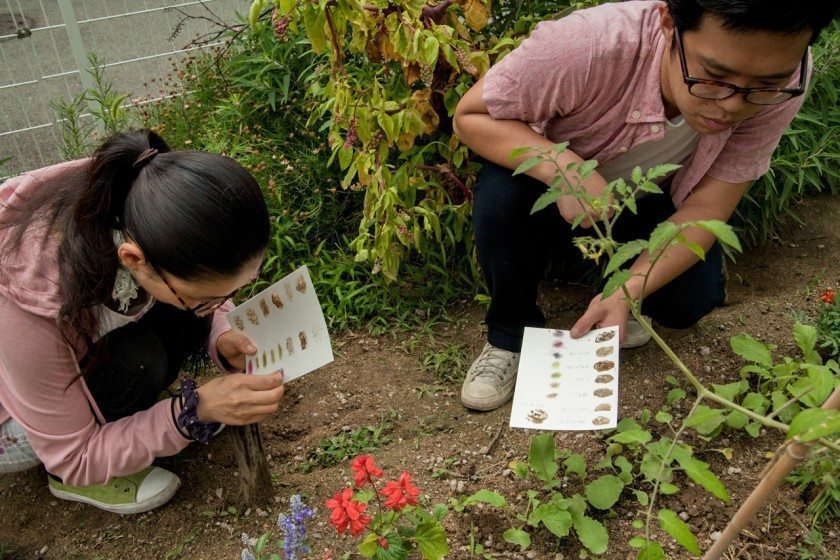

By example, during one such “soil art” workshop, we began with exploring how there are millions of living things in each square inch of soil and how all of these living things work together to provide a nurturing home for other life to grow. Together with the participants, we then asked these living beings with a sincere respect—again, the instructor’s understanding, attitude, and sincerity is an absolute requirement here—to lend us their color and texture, so that we might share their beauty through our artwork.

At this point, paintbrushes were dipped directly into the moist soil, and some deeply expressive and meaningful artworks emerged.

Along with the artworks came new perspectives from participants. A visitor from Tokyo told us that she always had a fondness for flowers and for how beautiful they are…but that it was a kind of common or easy beauty to appreciate. “Now for the first time in my life” she said “I can finally see how amazingly beautiful the soil is, too.”

Another participant, an undergraduate design student from Thailand, decided to change his thesis project after seeing how strongly nature could help direct his design. One also noticed, of her own accord, how the colors that the plants produce changed radically based on her intentions and how she approached using the plant. She demonstrated by gently and gracefully rubbing a white flower on paper, producing a beautiful ocean blue hue, and then again, more violently rubbing the same petal and watching as the hue started out blue and then quickly turned brown while the other stayed blue.

These kinds of discoveries and reactions weren’t prompted or dictated by us, but found by the individual participants as they more deeply connected with the garden itself. Nor are they uncommon reactions.

It seems that simply giving people the ‘permission’ to work with respect with nature, and to cultivate meaningful relationships, can offer such an amazing release for them. All of a sudden, their connectedness, acceptance, and creative mindsets blossom in ways they would each have thought were radical or impossible before.

We were lucky to have participants from the age of 5 to the age of 70, and most all of them had relatively little trouble flipping this mental switch to engage their surroundings in deeper ways.

Aiming for the long term

The REALtimeFOOD project was a hub for compassion, creativity, and well being for locals and visitors from around Japan and internationally. It was a project that we think created a positive ripple of compassion and well being in the small neighborhood of Kitakagaya and beyond.

That’s all warm and fuzzy.

The other reality is that this was a short-term project funded by the grant-making arm of a real estate firm that owns most of the land in this ailing neighborhood.

We know the reality of this situation is that the story typically ends in higher property values, higher rents, higher incomes, gentrification, and the removal of the creative class and the gardens which are on land that is suddenly far too ‘valuable’ for agriculture and silly creative deep ecology projects and the millions of tiny creatures in a square inch of soil.

The question is always, how do we make it economically viable? And ends with discussions along the lines of: how does a parking lot compare with an active community garden in terms of economic value?

It doesn’t, of course, and the first answer of those working in this space is generally something like “we need to get it through our thick heads that such projects offer value far beyond the economic. There’s social and ecological value too, and we must measure it!”

Let’s not stop the conversation here, though. The result of urban ecological features and programs which bring depth, relationships, and relevance to these natural features, offers value far beyond any social or ecological valuations that we can calculate and graph.

The value of a useless hole in the ground

What is the value when an office worker stops his stride and takes a deep breath while admiring a garden on his way home from work? What is the value when a gardener shares flowers with a local restaurant every week to brighten up the tables, or when a child stops by a garden to enthusiastically dig holes in the soil—even if they are not needed—with a smile so big it’s as if it’s the most joyful thing he’s ever done?

Not only do these values elude economic justification, they can not even be properly calculated with any type of measurement or categorization we might come up with, economic or not; yet, they are absolutely the kinds of values that make life true, beautiful, and good.

The end result of an active urban garden is not a number, whether that number is reduction in crime or a point rise in the quality of life index. The end result is the re-connection of human beings with an immeasurable, intangible, essential part of what makes life worth living.

A parking lot does not make life worth living, nor does an apartment tower.

Does a relationship with the natural world make life worth living? Of course, a relationship with nature is life in no uncertain terms. Our personal understanding of this relationship is a part of being human which has been omnipresent in our species for millions of years not just for the nearly invisible space on our historical timeline occupied by the industrial age.

With respect to human and nature relationships, a few understandings about our current social attitude towards nature have come out of these workshops, including that:

- Our connection to nature is a part of life that our culture has either lost or seriously devalued, and ironically much of this devaluation has recently come through our earnest efforts to put a value on it in the first place!

- Our efforts to value nature are clear signs that we have no idea what the value of nature is.

- Our rejection of a compassionate relationship with nature as an invaluable and integral part of life hurts us humans as much as it hurts the rest of our natural world.

- Our mental and physical disconnection from nature hurts all of earth’s beings, socially and ecologically, without discrimination.

Establishing a new value system

It is important that active community gardens, and natural spaces in general, should be seen as long-term public services because they offer a foundation for social and ecological well-being which is necessary for strong, happy, and economically productive communities. Establishing such a mentality might sound impossible given today’s political and business climate, yet the secret is that we know it is not nearly as impossible as most people think.

Even though our relationship with nature has been devalued and brushed away by most city dwellers, the surprising results of our own efforts to reignite this relationship indicate that human beings are quite easily able to connect with nature on some more meaningful level. We just need a little help.

From our perspective of doing REALtimeFOOD and other similar projects, the requirements are maddeningly simple.

We need to provide:

Ample opportunities (places) to connect with nature – these needn’t be big, but they must contain growing things that are easily accessible, where people are allowed to touch and interact with them, not just look at them from behind a wall

A bit of guidance and social permission – through a combination of sincerely led workshops, signage, and public education, guiding people to use their own capacity for connection and creativity and letting them know that yes, it’s okay to hug that tree, it’s okay to talk to that plant, it’s okay to say thank you to the soil.

Once we try it, we remember quite easily. We remember our part in the world. We remember the power of compassion and connection.

When we re-connect with nature—in the most remote mountains or in the most dense city—we can remember, in no uncertain terms, what it is to be human.

If we truly see ourselves as a part of nature, then the value of this understanding must be seen as a core value of life itself, and a value that no other interest, political, economic, or social, should be allowed to trump, and for which I would step out on a limb to say, the bulk of our human efforts at this point for our species and this planet must be given to fully and freely.

Plus, the tomato jelly is just amazing. Honest.

Patrick Lydon

San Jose & Seoul

As an urban ecologist, I’ve studied the house sparrow, the “agrarian” (as we call it in some Mexican regions), for over a decade now, and had never been aware of the infinity of human expressions related to sparrows in general. In this book, Todd gathers an impressive cumulus of facts, stories, and references to the generic concept of “sparrow” together with an exquisite palette of artwork by artists from around the globe.

As an urban ecologist, I’ve studied the house sparrow, the “agrarian” (as we call it in some Mexican regions), for over a decade now, and had never been aware of the infinity of human expressions related to sparrows in general. In this book, Todd gathers an impressive cumulus of facts, stories, and references to the generic concept of “sparrow” together with an exquisite palette of artwork by artists from around the globe.

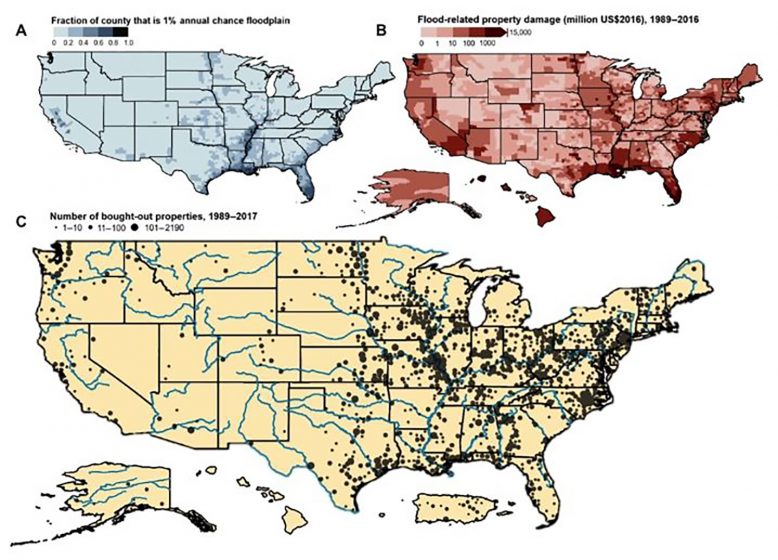

Connecting the center of the island to the beaches of San Juan, the Río Piedras watershed embodies both celebration and fear. Heavy rains occasionally transform its calm waters into torrents, inundating the city streets. And when hurricanes hit, the once tranquil sea metamorphoses into a tumultuous and vindictive paramour, unleashing its fury with relentless force.

Connecting the center of the island to the beaches of San Juan, the Río Piedras watershed embodies both celebration and fear. Heavy rains occasionally transform its calm waters into torrents, inundating the city streets. And when hurricanes hit, the once tranquil sea metamorphoses into a tumultuous and vindictive paramour, unleashing its fury with relentless force.

Overall, the Alianza and the local community are demanding fair and transparent processes for understanding the causes and impacts of flooding, including the relationship between flood mitigation options and the values, fears, and concerns of San Juan residents. These can be addressed by collaboratively building representations of the urban system, more broadly considering social-ecological relationships, and explicitly evaluating how citywide NbS fit within a more comprehensive climate resilience strategy.

Overall, the Alianza and the local community are demanding fair and transparent processes for understanding the causes and impacts of flooding, including the relationship between flood mitigation options and the values, fears, and concerns of San Juan residents. These can be addressed by collaboratively building representations of the urban system, more broadly considering social-ecological relationships, and explicitly evaluating how citywide NbS fit within a more comprehensive climate resilience strategy.

1 Comment

Join our conversation