1. A just city repositions inequality

1. A just city repositions inequality

The conversation about justice and the city must begin with directly confronting social and economic inequality and prioritizing them as the main issue around which institutions must be reorganized. Contemporary architectural and urban practices must engage this political project head-on. We must question the neoliberal hegemony that has been imposed on the city in recent decades, which has exerted a violent blow to our collective economic, social and natural resources, producing an anti-public agenda whose ultimate consequence is an ever-widening gap between rich and poor.

If we are interested in the Just City, we must begin by confronting the political machinery that endorses uneven urban development.

Today’s urban crisis is exponentially complex, as the consolidation of exclusionary power is both economic and political in nature, driven by one of the largest corporate lobbying machines in history. In the name of freedom, this machine has deregulated and privatized the public assets of our cities, subordinating collective responsibility to serve individual interest. Though the term “crisis” has become ubiquitous, we have become institutionally paralyzed in the context of these unprecedented shifts, silently witnessing the consolidation of the most blatant politics of exclusion, the shrinkage of social and public institutions and their role in the construction of the city. In that way, our crisis can’t be written off as a purely economic or environmental emergency. Rather, it is one of culture—a crisis of institutions unable to rethink unjust and unsustainable urban growth.

If we are interested in the Just City, we must begin by confronting the political machinery that endorses uneven urban development. In other words, we must possess critical knowledge of the conditions that produced our urban crisis. Without altering the exclusionary policies that have decimated our public culture today, urban design and planning will remain decorative enterprises camouflaging the greedy politics and economics of urban development that have eroded the primacy of public infrastructure worldwide.

In this context, the most relevant new urban practices and projects promoting social and economic inclusion are emerging not from sites of economic power but from sites of scarcity and zones of conflict, where citizens themselves, pressed by socioeconomic injustice, are pushed to imagine alternative possibilities. It is from the sense of urgency that a new political agenda is emerging, one in which urban design and architecture will take a more critical stance against the discriminatory policies and economics that produced inequality and marginalization. At this moment, it is not buildings but the fundamental reorganization of social and economic relations that is the essential for the expansion of democracy and justice in the city.

2. A just city reengages the public

Since the early 1980s, with the ascendance of neoliberal economic policies based on the deregulation and privatization of public resources, an unchecked culture of individual and corporate greed has resulted in dramatic income inequality and social disparity. This new period of institutional unaccountability and illegality has been framed politically by the erroneous idea that liberty is the “right to be left alone,” a private dream devoid of social responsibility. But the mythology in which free-market “trickle down economics,” assures that we all benefit when we forgive the wealthy their taxes, has been proven wrong by political economists Saez and Piketty. They have exposed that both great economic upheavals in 20th century America—the crashes of 1929 and 2008— were also periods of the largest socioeconomic inequality and the lowest marginal taxation of the wealthy. The deepening of inequality in America is a direct result of the polarization of public and private resources, and this has had dramatic implications for the erosion of public institutions, and the uneven growth of the contemporary city, with its dramatic increase of territories of poverty.

However, these trends are not inevitable. Broad, structural political and social changes are still possible. Such changes have occurred at certain moments in history, when the instruments of urban development were primarily driven by an investment in the public. For example, there was the New Deal in the U.S. after the 1929 crisis, when a multi-sector institutional momentum took place that re-engaged public priorities by investing in public infrastructure, housing and education to re-energize the economy. Or the post-war Social Democratic urban politics in Europe, that framed the urban and economic growth of the European city by investing in public goods, such as Mitterrand’s Grand Project for Paris. How do we reinvigorate public investment? And how do we ignite new forms of civic participation, to demand these investments?

A “just city” needs progressive public governance, driven by an ethical assertion that the good of the individual depends on the health of the collective, and an imperative to recalibrate the relations between individuals, collectives and institutions. At a time when the extreme right and the extreme left on the political spectrum share a distrust of government, we urgently need to reclaim the role of government to prioritize public interests, and enact the protection systems—social and economic—that can stem the trend toward radical inequality. We need a new political leadership that engages the marginalized sectors of our societies, committed to efficient, transparent, inclusive and collaborative forms of local governance.

3. A just city redistributes knowledge

Social Justice today is not only about the redistribution of resources; it should also promote the redistribution of knowledges. The polarization of public and private interests in the city has produced a rupture between institutions and publics. At the University of California San Diego, where we lead the Cross-Border Initiative, we have been pursuing new strategies of “knowledge exchange” between the top-down and the bottom-up. In one direction, we examine how specific, bottom-up urban activism can trickle upward to transform top-down institutional policy and practice; and, in the other direction, we investigate how top-down resources can reach sites of marginalization and support bottom up intelligence. This journey from the bottom-up to the top-down is urgent today to rethink urban justice, and it requires new forms of institutional representation and urban education that can translate and facilitate the everyday practices and needs of marginalized communities into new development logics for inclusive urbanization.

Our campus is barely thirty minutes away from the most trafficked border in the world, occupying one of the most contested and uneven trans-national global regions, where urbanizations of wealth and poverty collide and overlap daily. In the context of such social and economic disparity, many underserved neighborhoods in our region have constructed alternative models of urban sustainability, resilience and adaptation to redefine urban growth. We claim that learning from these bottom-up forms of local socio-economic production is essential to rethinking urban density through new strategies of urban coexistence and interdependence.

We created the Cross-Border Community Stations Project as a platform for these exchanges, linking the specialized knowledge of the university with the community-based knowledge embedded in marginal neighborhoods on both sides of the border. This two-way flow, as universities engage communities but also communities enter into the universities, suggests the need for new forms of teaching and learning that can expand pedagogical processes beyond the classroom and embed them in the everyday social life of communities.

This encounter between formal and informal knowledge requires new conceptions of public space, as a space of education and knowledge production. This involves the transformation of empty spaces into active civic classrooms, spaces of knowledge, research production and local economy. The University of California, San Diego refers to these field-based laboratories as “Community Stations,” new public spaces where research, teaching and community activism are co-curated collaboratively and where a new environmental literacy and cultural action can stimulate political agency at the scale of communities.

In particular, this collaborative urban pedagogical model between research universities and local community-based agencies emphasizes that marginalized communities and major universities can be meaningful partners with knowledge and resources to contribute, in the search for solutions to deep social and economic challenges, to improve the quality of life across these underserved, demographically diverse neighborhoods.

4. A just city rethinks beautification

A Just City will move the idea of beautification from aesthetics for aesthetics’ sake into an expanded, more complex idea of beauty. As cities become increasingly defined by architecture that only serves to camouflage and deepen exclusionary politics and economics, it is urgent that we challenge the steady march of decorative revitalization.

Beautification has long been an excuse for the displacement of communities. Yet today, the issue seems more relevant than ever, given the way it has been leveraged for exclusionary ends by seemingly progressive urban agendas such as New Urbanism and the Creative Class movements. It is not enough for New Urbanism, with its obsession with form-based code and stylistic historicism, to retrofit suburbia with a “prettier” themed façade, if the ownership models that define such infill developments remain mono-cultural, aesthetically homogeneous and unaffordable. These neoconservative urban trends have been adopted by many municipalities across the U.S., and have done nothing to rethink existing models of property by redefining affordability and the value of social participation, enhancing the role of communities in coproducing housing, or enabling a more inclusive idea of ownership.

Equally, the Creative Class agenda has only capitalized on the aesthetics of cosmopolitan hipster enclaves that are supposedly driven by artists and cultural producers, without providing truly affordable rents for artists and accessible infrastructures for fabrication and cultural production that are necessary to incentivize local economic growth in and for neighborhoods. With their facades of beautification and innovation, both agendas pave the way to gentrification and fail to advance social or economic justice in the city.

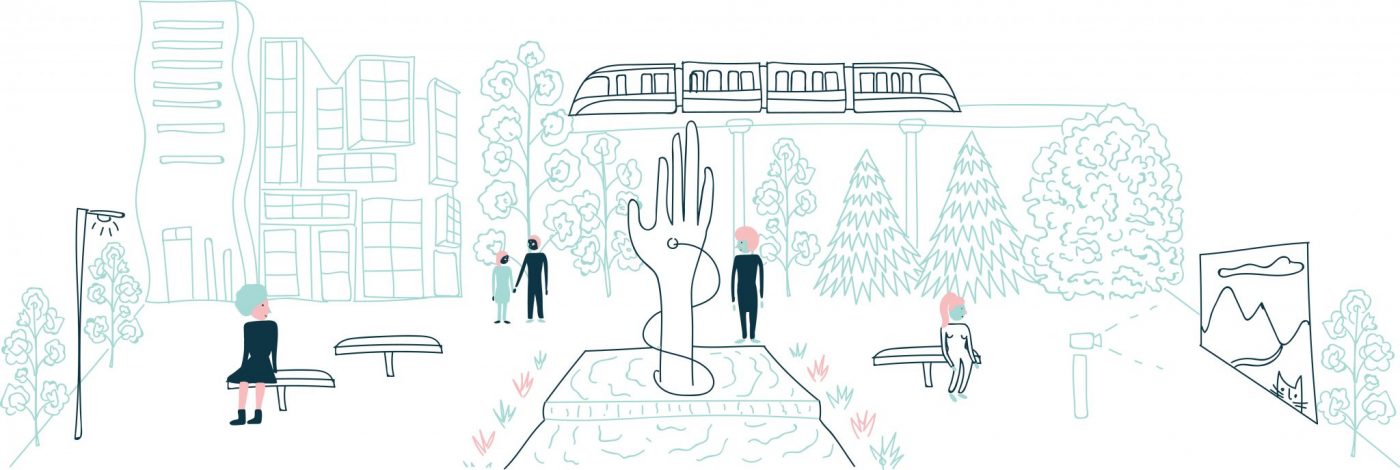

The Just City requires a more experiential dimension of beauty, less based on a visual quality and more on a sort of subliminal drama and vibrancy, a process of encountering and co-existing with the “other;” an aesthetic quality that embraces contradictions. It is about the construction of a sense of aesthetics that requires risk. In other words, it is an idea of beauty that does not smother and suppress contradictions or conceal conflict, but emerges out of socio-economic and political inclusion. A city is beautiful to the extent that it is inclusive, and one whose public spaces are not merely catalysts for architectures of privatization, but are generative of urbanizations of social justice.

5. A just city reimagines citizenship

Antanas Mockus, former Mayor of Bogota, Colombia, insisted that before transforming the city physically, we need to transform social norms. To Mockus, urban transformation is as much about changing patterns of public trust and social cooperation from the bottom-up as it is about changing urban, public health and environmental policy from the top-down. Mockus enacted a distinctive kind of egalitarian political leadership, declaring emphatically the moral norms that should regulate our relations: that human life is sacred, that radical inequality is unjust, that adequate education and health are human rights and that gender violence is intolerable. He reorganized public policy by nurturing a new citizenship culture, grounded in a moral claim that human beings—regardless of formal legal citizenship, regardless of race—have dignity, and deserve equal respect and basic quality of life.

In rethinking urban justice, Mockus developed a corresponding urban pedagogy of distinctive performative interventions to demonstrate precisely what he meant, inspiring generations of civic actors, urbanists and artists across Latin America and the world to think more creatively about engaging social behavior. Meeting urban violence with stricter penalties will not work. Law and order solutions don’t interiorize new values among the public.

For example, he believed in modeling desired behavior by, for example, showering on public television to demonstrate how one turns off the water when soaping up. One famous example of urban pedagogy is that early in his administration, Mockus replaced the corrupt downtown traffic police force with a troupe of 500 street mimes who stood on street corners and shamed traffic violators by blowing whistles, and pointing, and holding up signs of disapproval: “incorrecto!” To many it looked like a circus, and Mockus drew criticism; but in this act of public shaming, the mimes were instituting a new social norm of compliance with traffic signs; and it worked. Their antics became a citywide sensation; every one was watching on television, and traffic fatalities declined by 50% in Mockus’ first administration. Additionally, Mockus distributed placards across the city, one with a thumbs up sign, the other with a thumbs down; and he encouraged citizens to use these placards to communicate approval and disapproval to one another. The changes were palpable: people began to look at each other and recognize each other. In a very short period of time, a new sense of civic responsibility began to emerge in a city that had fallen into complete dysfunction and violence. At the same time, a new trust in government began to take hold as Mockus won the hearts of citizens, and he accompanied this bottom-up normative change with massive top-down municipal investment in social service and public works, improving peoples lives in very tangible ways. Naysayers could not deny the proof: During Mockus’ first administration, murders were reduced by 70 percent, traffic fatalities by 50 percent, tax collection nearly doubled, and water usage decreased by 40 percent while water and sewer services were extended to nearly all households.

What Mockus’ work demonstrates is that urban social norms can be reoriented through top-down municipal intervention through community processes. These are fundamental lessons that can be brought to the American city, primarily today when neighborhood violence has been exacerbated by the resurgence of racism and police brutality, but also by current anti-immigration ideology, which together with the exclusionary policies it engenders has deepened injustice in the city.

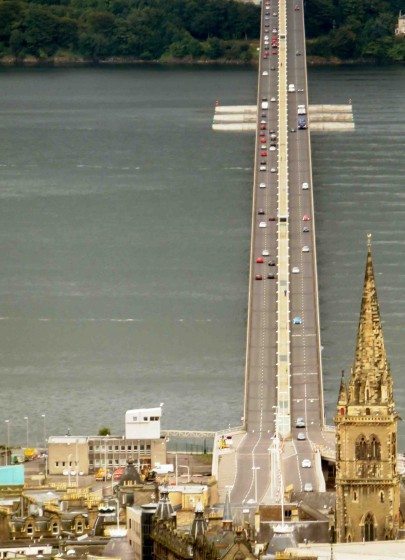

From the vantage point of the border territory where we live and work, social norms here have incrementally hardened against immigrants and immigration, alongside the hardening of the legal, social, economic and physical walls between the United States and Mexico. Our borders have been militarized in tandem with legislation that erodes social institutions, barricades public space and divides communities. Such protectionist strategies, fueled by paranoia and greed, are defining a radically protectionist social agenda of exclusion that threatens to dominate public life for years to come.

A community is always in dialogue with its immediate social and ecological environment: this is what defines its political nature. But when the productive capacity of a community is splintered by political borders, it must find ways to recuperate its social agency and entrepreneurial potential. This is why we have always been inspired by the poor, immigrant neighborhoods on both sides of the San Diego-Tijuana border, whose residents are redefining urban sustainability and pointing to new ways of constructing citizenship. A just city depends on a political leadership that recognizes our interdependence and reaches across borders to produce new strategies of coexistence. And it is precisely within the marginalized yet resilient immigrant communities flanking the border that such a conception of civic culture will emerge, one whose DNA is composed of empathy, collaboration and shared values.

Isolationism is no longer an option in today’s world of global interconnectedness. Ethically, we cannot ignore the negative impact that our decisions, choices and habits have on others near and far; nor can we impose our will on others by force. The problems of Mexico and Central America are ours. The fallout of climate change on the global poor, most of which the rich countries of the North have caused, is our responsibility. The dramatic injustices perpetrated against marginalized populations in Ferguson, MO and undoubtedly countless other cities across the U.S. cannot remain invisible, isolated from the halls of Washington. We cannot wish the problems of such places away with market solutions, or with guns and fences; instead we must listen to and cooperate with those most affected by our policies, globally and domestically.

At bottom, we need to recover a sense of collective commitment to the least well-off among us. Social justice must reassert itself at the center of today’s public discourse, and we must also recover a sense of cultural empathy, the sort emblazoned on the Statue of Liberty’s plaque:

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

In a just city, economic and urban growth cannot come at the expense of social equality and inclusion. The drive to privatize must be tempered by an interventionist, disruptive commitment to public investment in infrastructure and general social welfare. The market will not solve our problems. Public and private interests must be harmonized. The public, particularly the poorest members of it, must take their cities back. Government must become transparent, efficient, and inclusive, with massive investment in new strategies of civic engagement to reignite a new public culture capable of making claims on its own behalf. Today, mistrust of government and hollow notions of progress and freedom for all have undermined the possibility of drawing upon the shared democratic values that unite us. Citizenship has become a polarizing concept, caught up in narratives about protecting “our” resources from “them.” In the just city, a more inclusive citizenship culture, based on shared values, commitments and common interests, rather than rigid jurisdictional categories that dehumanize the other, must be the foundation of a new public imagination.

Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman

San Diego

The Just City Essays is a joint project of The J. Max Bond Center, Next City and The Nature of Cities. © 2015 All rights are reserved.

Fonna Forman is a Professor of Political Theory at the University of California, San Diego and founding Director of the UCSD Center on Global Justice. Current work focuses on climate justice in cities, on human rights at the urban scale and civic participation as a strategy of equitable urbanization.

People of color are at the center of a demographic shift that will fundamentally change the global urban landscape. From the growing proportions of Latino, Asian, and African American residents in resurgent cities of the United States, to the diversifying capitals of Europe and the booming metropolises of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, cities populated by people of color are emerging as the new global centers of the 21st century.

People of color are at the center of a demographic shift that will fundamentally change the global urban landscape. From the growing proportions of Latino, Asian, and African American residents in resurgent cities of the United States, to the diversifying capitals of Europe and the booming metropolises of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, cities populated by people of color are emerging as the new global centers of the 21st century.

I am the mayor of a legacy city, a city that rose and fell on the fluctuations of an industrial marketplace. Like Detroit, Cleveland, and dozens of other cities that have experienced continuous population and job loss since their peak, my hometown of Gary, Indiana, once provided the backbone of the nation’s economy. These cities led the way in educational innovation, architectural design and cultural development. In the 1920s, Gary earned the nickname of Magic City because of its exponential growth. Seventy years later, one half of the city’s population is gone, leaving an overwhelming inventory of vacant and abandoned buildings, a nearly 40 percent unemployment rate and a 35 percent poverty rate in the rear view mirror.

I am the mayor of a legacy city, a city that rose and fell on the fluctuations of an industrial marketplace. Like Detroit, Cleveland, and dozens of other cities that have experienced continuous population and job loss since their peak, my hometown of Gary, Indiana, once provided the backbone of the nation’s economy. These cities led the way in educational innovation, architectural design and cultural development. In the 1920s, Gary earned the nickname of Magic City because of its exponential growth. Seventy years later, one half of the city’s population is gone, leaving an overwhelming inventory of vacant and abandoned buildings, a nearly 40 percent unemployment rate and a 35 percent poverty rate in the rear view mirror.

In the United States of America

In the United States of America

Soil contamination is a baseline condition for most of the sites I’ve worked on over the past two decades. The toxic imprint derives from industry—steel production, shipbuilding, fabrication of automobile and machine parts, to name just a few—in both urban and rural settings. But it also comes from lead-containing gasoline and paint, banned long ago but still quietly wreaking havoc. It’s a byproduct of the human pursuit of greater material wealth and a more convenient and comfortable life. In other words, it’s the legacy of progress, for better or worse.

Soil contamination is a baseline condition for most of the sites I’ve worked on over the past two decades. The toxic imprint derives from industry—steel production, shipbuilding, fabrication of automobile and machine parts, to name just a few—in both urban and rural settings. But it also comes from lead-containing gasoline and paint, banned long ago but still quietly wreaking havoc. It’s a byproduct of the human pursuit of greater material wealth and a more convenient and comfortable life. In other words, it’s the legacy of progress, for better or worse.

1. A just city repositions inequality

1. A just city repositions inequality

If you have never been to Baltimore, you should come to visit. From Baltimore Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport, you can ride the light rail to downtown in 25 minutes for one of the best deals in the country. If you ride the train between Boston and Washington, you can walk out of Pennsylvania Station and board the Charm City Circulator to downtown, and it’s free! However, if you live in the city of Baltimore and you want to rely on transit to get you to all of life’s functions, you need to recalculate your aspirations for life’s necessities and ambitions. For the 30 percent of people who live in Baltimore without a car (which, coincidentally corresponds with the percentage of people between 16 and 64 not in the labor force), the pursuit of economic opportunity, particularly beyond the confines of downtown, comes with limitations.

If you have never been to Baltimore, you should come to visit. From Baltimore Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport, you can ride the light rail to downtown in 25 minutes for one of the best deals in the country. If you ride the train between Boston and Washington, you can walk out of Pennsylvania Station and board the Charm City Circulator to downtown, and it’s free! However, if you live in the city of Baltimore and you want to rely on transit to get you to all of life’s functions, you need to recalculate your aspirations for life’s necessities and ambitions. For the 30 percent of people who live in Baltimore without a car (which, coincidentally corresponds with the percentage of people between 16 and 64 not in the labor force), the pursuit of economic opportunity, particularly beyond the confines of downtown, comes with limitations.

It was close to midnight. A youngish, jovial-looking white woman with russet colored hair ran by me with ostensive ease. She donned earphones and dark, body-fitting jogging attire. I was walking home from the A train stop and along Lewis Avenue, which is a moderately busy thoroughfare that runs through the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in central Brooklyn, where I live.

It was close to midnight. A youngish, jovial-looking white woman with russet colored hair ran by me with ostensive ease. She donned earphones and dark, body-fitting jogging attire. I was walking home from the A train stop and along Lewis Avenue, which is a moderately busy thoroughfare that runs through the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in central Brooklyn, where I live.

My vision for a just city is one where design and its power as a tool against inequality is leveraged for the benefit of all residents. As the director of design programs at the National Endowment for Arts, and one of the U.S. government’s primary advocates for good design, I spend a lot of time with mayors and other leaders advocating for the power of design. In the words of Charleston, South Carolina Mayor Joseph Riley, a mayor is “the chief urban designer” of his or her city. Even so, most mayors require education on what design can do—and what it cannot do.

My vision for a just city is one where design and its power as a tool against inequality is leveraged for the benefit of all residents. As the director of design programs at the National Endowment for Arts, and one of the U.S. government’s primary advocates for good design, I spend a lot of time with mayors and other leaders advocating for the power of design. In the words of Charleston, South Carolina Mayor Joseph Riley, a mayor is “the chief urban designer” of his or her city. Even so, most mayors require education on what design can do—and what it cannot do.

In 1993 or thereabouts I entered a contest for women to depict what they did on a particular day. That day, I went to meetings early in the morning at Harlem Hospital. I took photos of the abandoned buildings on West 136th, where I parked my car, and photos of a huge plastic bag in one of the stunted trees. Later, on my way back to my office on W. 166th Street, I stopped to take a photo of man who was selling nuts on the street in front of a burned-out building. He smiled with tremendous pride—when I took him a copy of the photo a few weeks later, he grinned and said he’d send it to his mother so she would know he was trying to make something of himself. There were photos of the Stuyvesant High School students that I was mentoring for the Westinghouse Science Competition, and photos at home in Hoboken with my daughter Molly and some chocolate chip cookies fresh out of the oven. We were reading Ian Frazier’s New Yorker article about plastic bags in trees. I didn’t win the contest, but the exercise etched what I saw in memory.

In 1993 or thereabouts I entered a contest for women to depict what they did on a particular day. That day, I went to meetings early in the morning at Harlem Hospital. I took photos of the abandoned buildings on West 136th, where I parked my car, and photos of a huge plastic bag in one of the stunted trees. Later, on my way back to my office on W. 166th Street, I stopped to take a photo of man who was selling nuts on the street in front of a burned-out building. He smiled with tremendous pride—when I took him a copy of the photo a few weeks later, he grinned and said he’d send it to his mother so she would know he was trying to make something of himself. There were photos of the Stuyvesant High School students that I was mentoring for the Westinghouse Science Competition, and photos at home in Hoboken with my daughter Molly and some chocolate chip cookies fresh out of the oven. We were reading Ian Frazier’s New Yorker article about plastic bags in trees. I didn’t win the contest, but the exercise etched what I saw in memory.

There is a difference between equality and equity. Equality says that everybody can participate in our success and equity says we need to make sure that everybody actually does participate in our success and in our growth. A just city is a city free from both inequity and inequality.

There is a difference between equality and equity. Equality says that everybody can participate in our success and equity says we need to make sure that everybody actually does participate in our success and in our growth. A just city is a city free from both inequity and inequality.

The purpose of this essay is to share some considerations about the meaning of “just City” from the perspective of a lawyer dedicated to the reform of justice administration and, in particular, to the design of systems that promote, encourage and facilitate the approach of justice for the people. This historically means not only a change in the rules and culture but also a change in the design of the spaces in which justice is administered.

The purpose of this essay is to share some considerations about the meaning of “just City” from the perspective of a lawyer dedicated to the reform of justice administration and, in particular, to the design of systems that promote, encourage and facilitate the approach of justice for the people. This historically means not only a change in the rules and culture but also a change in the design of the spaces in which justice is administered.

There are two main legacies that define urban inequality in South Africa: housing and transport. Apartheid was not only a racial ideology. It was also a spatial planning ideology.

There are two main legacies that define urban inequality in South Africa: housing and transport. Apartheid was not only a racial ideology. It was also a spatial planning ideology.

I have lived in an array of fascinating cities, and visited a host of others. I have loved many (New York, Hong Kong, Harare and Berlin); been miserable in a few (London and Pretoria); oddly disappointed by some (San Francisco, Dublin and Sydney) overwhelmed by others (Shanghai and Cairo); and frankly terrified by at least two (Port Moresby and Lagos).

I have lived in an array of fascinating cities, and visited a host of others. I have loved many (New York, Hong Kong, Harare and Berlin); been miserable in a few (London and Pretoria); oddly disappointed by some (San Francisco, Dublin and Sydney) overwhelmed by others (Shanghai and Cairo); and frankly terrified by at least two (Port Moresby and Lagos).

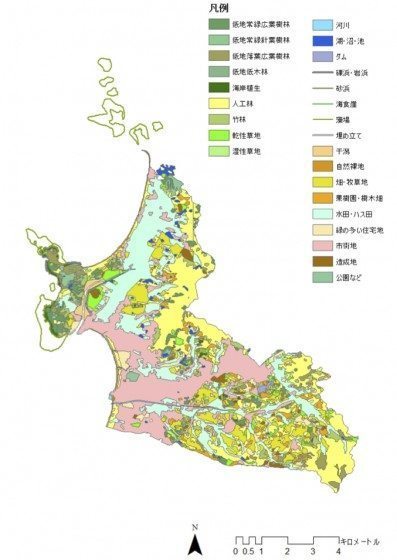

Since humans settled about 10,000 years ago, we have significantly altered and explored the landscape to create the civilization we now have. The landscape has been a source of material and non-material resources, feeding us in all senses. Ecologically rich landscapes associated with technologies were essential for all societies to emerge. The shape of landscapes along our history, have reflected how we produce our habitat and the goods that sustain us, our economies, and the way we live and relate to each other.

Since humans settled about 10,000 years ago, we have significantly altered and explored the landscape to create the civilization we now have. The landscape has been a source of material and non-material resources, feeding us in all senses. Ecologically rich landscapes associated with technologies were essential for all societies to emerge. The shape of landscapes along our history, have reflected how we produce our habitat and the goods that sustain us, our economies, and the way we live and relate to each other.

Try as you might, you’re no urbanite

Try as you might, you’re no urbanite

The birth of Paleo Cities

The birth of Paleo Cities

Resilience is the word of the decade, as sustainability was in previous decades. No doubt, our view of the kind and quality of cities we as societies want to build will continue to evolve and inspire new descriptive goals. Surely we have not lost our desire for sustainable cities, with ecological footprints we can afford, even though our focus has been on resilience, after what seems like a relentless drum beat of natural disasters around the world. The search for terms begs the question: what are the cities we want to create in the future? What is their nature? What are the cities in which we want to live? Certainly these cities are sustainable, since we want our cities to balance consumption and resources so that they can last into the future. Certainly they are resilient, so our cities are still in existence after the next 100-year storm, now due every few years. And yet…as we build this vision we know that cities must also be livable. Indeed, we must view livability as a third indispensible leg supporting the cities of our dreams: resilient + sustainable + livable.

Resilience is the word of the decade, as sustainability was in previous decades. No doubt, our view of the kind and quality of cities we as societies want to build will continue to evolve and inspire new descriptive goals. Surely we have not lost our desire for sustainable cities, with ecological footprints we can afford, even though our focus has been on resilience, after what seems like a relentless drum beat of natural disasters around the world. The search for terms begs the question: what are the cities we want to create in the future? What is their nature? What are the cities in which we want to live? Certainly these cities are sustainable, since we want our cities to balance consumption and resources so that they can last into the future. Certainly they are resilient, so our cities are still in existence after the next 100-year storm, now due every few years. And yet…as we build this vision we know that cities must also be livable. Indeed, we must view livability as a third indispensible leg supporting the cities of our dreams: resilient + sustainable + livable.

And so they are difficult to take in, both for their beauty and their complexity. How can you describe and assess them? Convey them to one who hasn’t seen? You finally stumble, awestruck, into saying that they are “beautiful,” or “majestic,” or just “amazing.” But all of us—as scientists, decision-makers, participating citizens—typically have to comprehend, describe and quantify such entities and then communicate the results in ways that aren’t hopelessly obscure—that are somehow specific and not just metaphorical. That is, we need to communicate a very complicated thing in a simple, essential and, above all, useful way.

And so they are difficult to take in, both for their beauty and their complexity. How can you describe and assess them? Convey them to one who hasn’t seen? You finally stumble, awestruck, into saying that they are “beautiful,” or “majestic,” or just “amazing.” But all of us—as scientists, decision-makers, participating citizens—typically have to comprehend, describe and quantify such entities and then communicate the results in ways that aren’t hopelessly obscure—that are somehow specific and not just metaphorical. That is, we need to communicate a very complicated thing in a simple, essential and, above all, useful way.

1 Comment

Join our conversation