about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David's dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to "fall back on". So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

Photography, and art in general, can help us see. See in new ways. Indeed, it helps us be better at looking. One of the main themes of The Nature of Cities is the idea of “nature nearby”—that cities are not barren of nature, but rather teem with life, both human and non-human. This nature provides services from storm water management to habitat to beauty. Indeed, cities are ecosystems of nature, people, form, and space. Cities are human habitat, and are better designed and maintained when we appreciate them as such.

Yet many people in cities don’t see that nature around them, though they may sense it as part of the nature, or character of their city. Can we learn to look more thoughtfully, and therefore see more fully the natural vibrancy that is all around us in cities? And also along the way see what vibrancy our cities may be lacking? It is a vibrancy that weaves—or should weave—together nature and people and built form in ways that make cities rich—rich in biodiversity, human society, sustainability, resilience, and livability.

So in the spirit of looking more deeply, more finely in ways that can help us see, this is the first of what I hope will be many roundtables on artistic and creative expression on the nature of cities. As is TNOC’s way, the 14 represented here take diverse routes to seeing and sensing the city. What details do they find to make the city more vivid?

about the writer

Joshua Burch

Hi I'm Josh, a 17 year old award winning wildlife photographer from the UK. As part of a young generation of conservationist I see my photography as a way to inspire others to appreciate its beauty and influence a positive awareness towards conservation.

Joshua Burch

I’ve grown up with an interest in nature since I was about 5, when I spent most of my time collecting all manner of bugs and creatures—generally, anything with more than two legs. My parents bought me my first camera at the age of 10 in the hope that it would reduce the number of escapees in our home!

Rather than grow out of it, my passion for the natural world has grown and now, as part of a young generation of conservationists, I see my photography as a way to inspire others to appreciate its beauty and influence a positive awareness towards conservation by actively supporting and contributing to initiatives like “A Focus On Nature“, a network for young conservationists.

I’m really keen to encourage and develop a network of young nature photographers and would love to connect with people, so please feel free to get in touch. I’m more than happy to share my experience and offer advice (I’m still learning as well), or simply to connect with anyone who shares my interest and passion.

about the writer

Emilio Fantin

Emilio Fantin is an artist working in Italy on multidisciplinary research. He teaches at the Politecnico, Architecture, University of Milan, and acts as coordinator of the “Osservatorio Public Art”.

Emilio Fantin

The relationship between culture and nature is at the very core of the question of the urban and any issues concerning the landscape.

The chair is one of the most powerful symbols of the western culture. It is an unmovable political and religious symbol of power.

At the same time, the chair recomposes the gap between time of nature and time of man; it evokes a moment of rest, a pause, a convivial and social function.

about the writer

Mike Feller

Mike Feller is an ecological consultant and nature photographer. He worked at NYC Parks for 31 years, where he was Chief Naturalist from 1987 until 2014.

Mike Feller

During the winter of 1985, I mapped archaeological features in the Bronx. One morning, as I stood in deep snow in the forest, I heard rustling behind me. Six feet away, a red-tailed hawk was struggling to subdue a squirrel. For the next half hour I watched the hawk gain control, eviscerate, and begin to eat its prey. I was close enough to see vapor waft from the squirrel’s body and to whiff bile. As the hawk flew away to finish her meal I resolved to buy a camera and begin to record my field experiences.

As a naturalist, photography serves me three ways. First, it allows me to create objective visual documents, record conditions, establish temporal baselines, and inventory specimens better left uncollected. Second, it satisfies my empirical need to record experiences and the aesthetic dimensions of places. It is also a powerful tool for creating experiences through storytelling, slide shows, and exhibits that reveal relationships and meaning to inspire interest, wonder, and sense of place. Third, photography is a conservation tool.

I am most invested in this last aspect. I know from my experience as a native New Yorker that for the majority, the iconic built city leaves no room in the imagination that beautiful, worthwhile natural areas exist. For most, the gargantuan asphalt and cement deck upon which the urban throng careens, is the subject. The estuary and the 22,000 acres of natural area is negative space. In New York Culture is figure, Nature is ground.

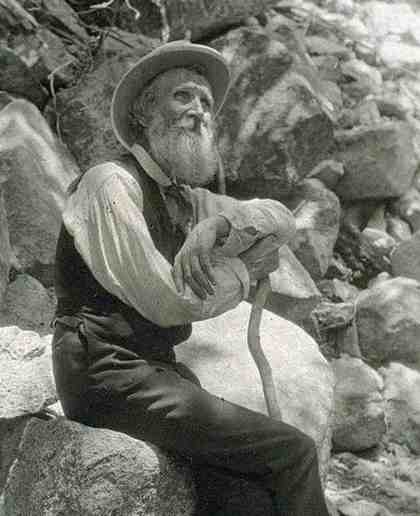

I want my images to confront and undermine this bias and to inoculate the viewer with the wonder, pleasure, and excitement or serenity that I experienced at the time and place of the photograph. My conservation heroes are John Muir and John Burroughs, Thomas Coale and Albert Bierstadt, William Henry Jackson and Ansel Adams: writers, artists, and photographers in the Romantic tradition who made their audiences feel deeply for their subjects and moved them to political action that resulted in the creation of national parks and state forest preserves.

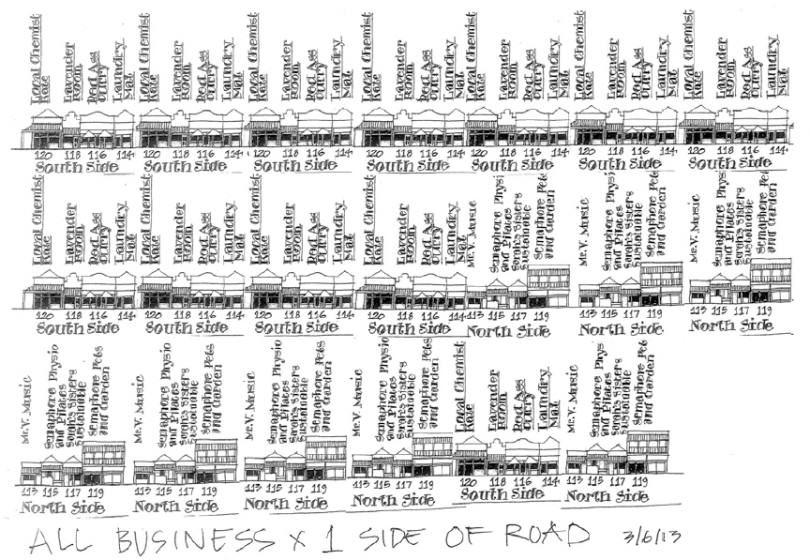

I have three approaches to photographing nature in New York, each represented here.

• I shoot landscapes with a 4×5 view camera. It is a deliberate, contemplative process and the subjects I am drawn to are serene places and moments. Some of these shots can take as long as an hour to set up, compose, and wait for light to change or the breeze to diminish. I attempt to exclude people and artifice.

• “The Tall Grass Zoo”, a children’s book about exploring small spaces and observing small creatures made a big impression on me as a child. It inspired me to lie where I grew up in the land-filled, weedy edges of Jamaica Bay with chin perched on my hands and watch insects. This was my first experience of the Romantic’s Sublime, described by Joseph Addison as, “…an agreeable kind of horror”. I focus on the small, simultaneously seductive and repulsive, with my macro photography. The diversity of form, color, and life history details of insects provides endless visual interest and descriptions of predator-prey relationships that would curl Edgar Allan Poe’s toes.

• The long telephoto lens is my means of revealing to others the details of the city’s wildlife that I have observed through binoculars. There is nothing quite like viewing for the first time the sapphire eye of a double-crested cormorant or the ruby eye of the black-crowned night heron, radiant jewels hidden in plain sight.

about the writer

Andrés Flajszer

Formed both as architect and photographer, Andrés lives and works in Barcelona. Since 2005 he develops a professional career in photography exploring the relational changes that take place between the built environment and human behavior as they define our contemporary condition.

Andrés Flajszer

Landscape is both object and representation at the same time. Originally a segment of the vast territory, a portion of land becomes a landscape when a multi-layered pack of forces (environmental, political, economical, social, etc.) shapes it in a specific way or direction. All landscapes have visible and invisible sides, always depending on the eye that beholds them. Ever since Nicéphore Nièpce succeeded in capturing his view from a window at Le Gras in 1826 (what is considered to be the first photograph is actually an image of an urban landscape), the world became obsessed with photography as the ultimate tool to capture reality in an accurate and permanent way, an exercise in revealing the truth. Almost two-hundred years have gone by—we’ve moved from daguerreotype to bits and bytes—and so Documentalism gradually gave way to Fiction. We no longer believe in or seek the absolute truth; rather, we try to understand the multiple realities, each real and artificial, that shape and define our Anthropocene world. So, from documentalism to fiction, I’m interested in witnessing the codes that are based on elements belonging to this bi-dimensional reality and, at the same time, that try to inhabit the in-between space enclosed by this apparent contradiction. The result portrays a wide range of elements, from people’s flow to architecture; they are brought to the world of imagery with no will to constitute a proof of reality, but rather to evoke the multiple forces that originated it. One last thing: whenever people are absent from the picture, that which is being portrayed makes them protagonist, because the urban landscape displays the traces of human presence written in our “new” nature.

about the writer

Mike Houck

Mike Houck is a founding member of The Nature of Cities and is currently a TNOC board member. He is The Urban Naturalist for the Urban Greenspaces Institute (www.urbangreenspaces.org), on the board of The Intertwine Alliance and is a member of the City of Portland’s Planning and Sustainability Commission.

Mike Houck

Much Beloved Beaver

In the early 1980s, we fought a three-year pitched battle to save Heron Pointe Wetland, the only remnant wetland on the West side of the Willamette River near downtown Portland, Oregon. The developer’s consultant argued, as even some natural resource agencies are wont to do, that the less- than-one-acre wetland was so small as to be insignificant from an ecological perspective. Those of us who engaged in efforts to protect the wetland, including a city commissioner’s staffer, a U. S. EPA wetland ecologist, citizen activists, and the Audubon Society of Portland, argued that while the wetland had less ecological value than the nearby 450-acre Ross Island archipelago, it’s true significance lay in the fact that thousands of people would pass by the wetland as they ran, walked or cycled on the Willamette Greenway trail. It would also hold great value, we argued, to the residents of the condominiums that sat adjacent to the trail.

Working with the commissioner of parks and the city’s park bureau, we installed an interpretive sign, hoping to educate passersby about the value of even this small remnant wetland. Thirty years later, an elderly resident of the adjacent Heron Pointe condos installed a two-foot tall bronze beaver to honor her husband, who had succumbed to Alzheimer’s. As the gnawed stumps of several cottonwood trees near the sign attest, her choice was ecologically apropos: beaver actually do use even the small wetland scrap, as do a surprising diversity of avifauna.

I have taken to walking the greenway trail on a five-mile loop twice a week for the past two years, and have been taken with how much the sculpture is loved by passersby. From day one, walkers seem unable to resist giving the beaver a pat on the head, leaving a token of small twigs, a flower, or some other token of their affection. More recently, one greenway frequenter has taken to bestowing seasonally appropriate attire on the beaver, whether it be Easter, Halloween, or the coming of spring. While I always look forward to seeing the feisty Anna’s Hummingbird fiercely guarding his nearby perch on a red-osier dogwood, I am sometimes even more delighted to see what new trinket, beaver-chewed twig, or outfit has been visited on what is a much beloved wetland icon.

Young Naturalist

Eight years ago, while leading a natural history tour of the 160-acre Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge, we fell in behind two parents who were, I assume, taking their young naturalist on a walk through the black cottonwood and big-leaf maple riparian forest. I was immediately reminded of Robert Michael Pyle’s book, “The Thunder Tree”, in which he postulated what has become one of my touchstones regarding our decades-long effort to ensure every child has access to nature nearby. Pyle, in a chapter titled “Extinction of Experience,” poses the question, “What’s the extinction of the Condor to a child who has never known a wren?”

Indeed. I have used this image numerous times, and it has even appeared in a prior The Nature of Cities blog by Marianne Krasny. The image of parents taking their happy little camper on a stroll in a wetland that is within a stone’s throw of downtown Portland represents to me the essence of urban nature. This young boy or girl (I’ve never come to a firm conclusion which, but am guessing boy) with the disproportionately large maple leaf has never failed to elicit a strong emotional response during numerous lectures, whether the audience members are agency ecologists, elected officials, or the general public. Long before Richard Louv launched what is now a national child-nature movement, Pyle started the conversation regarding the importance of nature to children’s emotional and physical well-being, regardless of the setting, but particularly in the urban context.

Condos and Great Blue Herons

I was paddling my kayak around Ross Island in downtown Portland and was blown away by the juxtaposition of the Great Blue Heron colony on the downstream tip of Ross Island with the new condominium towers at South Waterfront, Portland’s newest neighborhood on the west bank of the Willamette. We talk a lot in Portland about integrating the built and natural landscapes, and this comes close to what I have in mind regarding that effort, which we still have a long way to go to truly achieve. While the habitat improvements at South Waterfront have not panned out in the manner we had hoped it would twelve years ago, after two years of planning the Willamette River Greenway, the residents of the condos can now actually observe Bald Eagle picking young herons out of their nests. Not for the squeamish, perhaps, but pretty damn impressive in the heart of downtown Portland. This heron colony is the remnant of a 55-nest colony farther upstream on Ross Island, after the eagles took over six years ago. I have to say, having testified before our city council in 1979, almost forty years ago, to establish a 350-foot buffer around the heron colony from adjacent sand and gravel extraction, I beheld the eagle intrusion with mixed feelings. Still, we now have both eagles and herons sharing Ross Island, a stone’s throw from our CBD and one of Portland’s newest neighborhoods.

about the writer

Chris Jordan

Chris Jordan’s work explores the collective shadow of contemporary mass culture from a variety of photographic and conceptual perspectives. Edge-walking the lines between beauty and horror, abstraction and representation, the near and the far, the visible and the invisible, Jordan’s images confront the enormous power of humanity’s collective will.

Chris Jordan

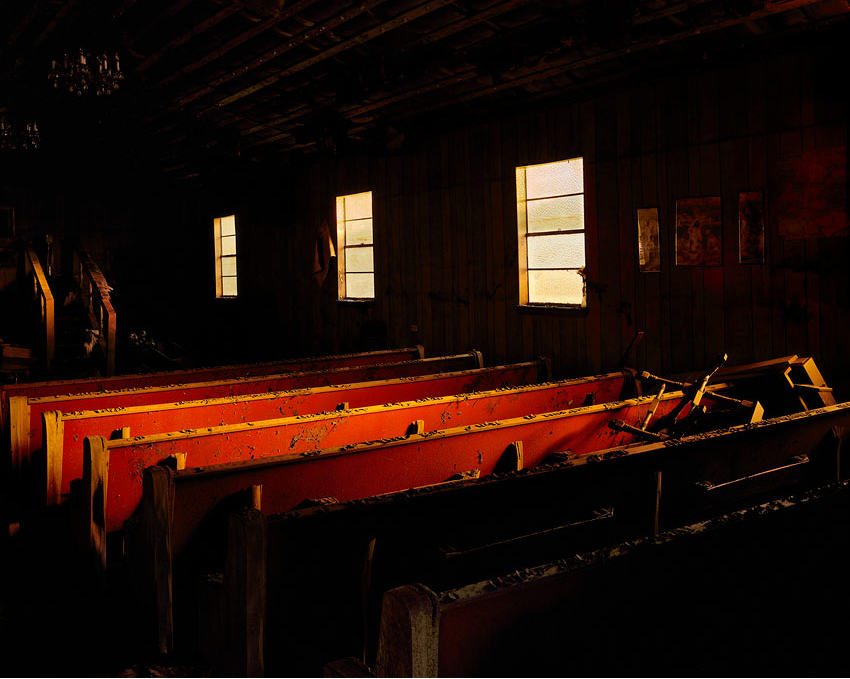

These images are drawn from three shows, each depicting scenes from the destructive and consumptive sides of human-nature interactions.

In Katrina’s Wake: Portraits of Loss from an Unnatural Disaster. This series, photographed in New Orleans in November and December of 2005, portrays the cost of Hurricane Katrina on a personal scale. Although the subjects are quite different from those in my earlier Intolerable Beauty series, this project is motivated by the same concerns about our runaway consumerism. There is evidence to suggest that Katrina was not an entirely natural event like an earthquake or tsunami. The 2005 hurricane season’s extraordinary severity can be linked to global warming, which America contributes to in disproportionate measure through our extravagant consumer and industrial practices. Never before have the cumulative effects of our consumerism become so powerfully focused into a visible form, like the sun’s rays narrowed through a magnifying glass. Almost 300,000 Americans lost everything they owned in the Katrina disaster. The question in my mind is whether we are all responsible to some degree.

Intolerable Beauty: Portraits of American Mass Consumption (2003 – 2005). Exploring the USA’s shipping ports and industrial yards, where the accumulated detritus of our consumption is exposed to view like eroded layers in the Grand Canyon, I find evidence of a slow-motion apocalypse in progress. I am appalled by these scenes, and yet also drawn into them. The immense scale of our consumption can appear desolate, macabre, oddly comical and ironic, and even darkly beautiful; for me its consistent feature is a staggering complexity. The pervasiveness of our consumerism holds a seductive kind of mob mentality. Collectively, we are committing a vast and unsustainable act of taking, but we each are anonymous and no one is in charge or accountable for the consequences. I fear that in this process we are doing irreparable harm to our planet and to our individual spirits.

As an American consumer myself, I am in no position to finger wag, but my hope is that these photographs can serve as portals to a kind of cultural self-inquiry. It may not be the most comfortable terrain, but I have heard it said that in risking self-awareness, at least we know that we are awake.

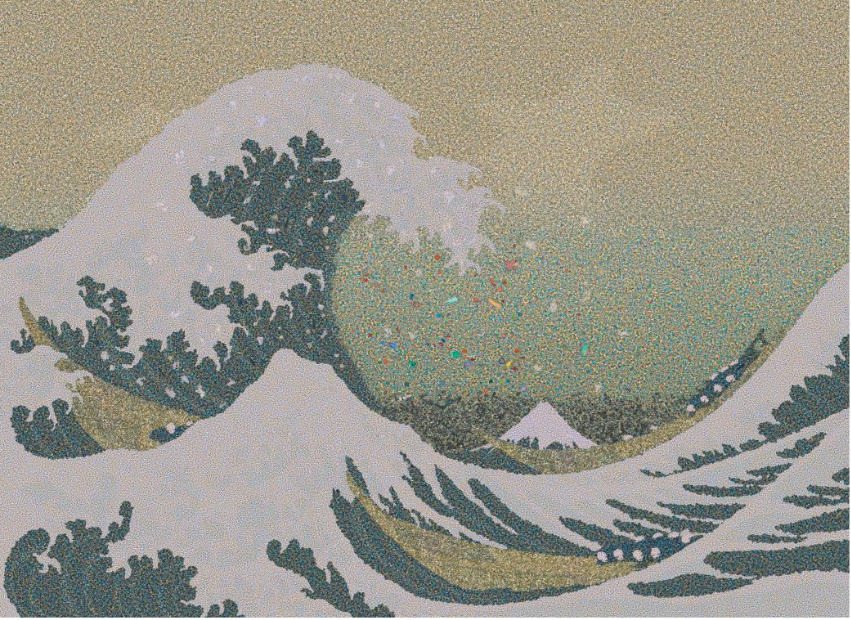

Running the Numbers II: Portraits of global mass culture (2009 – Current). This ongoing series looks at mass phenomena that occur on a global scale. Each image portrays a specific quantity of something: the number of tuna fished from the world’s oceans every fifteen minutes, for example. Finding meaning in global mass phenomena can be difficult because the phenomena themselves are invisible, spread across the earth in millions of separate places. There is no Mount Everest of waste that we can make a pilgrimage to and behold the sobering aggregate of our discarded stuff, seeing and feeling it viscerally with our senses. Instead, we are stuck with trying to comprehend the gravity of these phenomena through the anaesthetizing and emotionally barren language of statistics. Sociologists tell us that the human mind cannot meaningfully grasp numbers higher than a few thousand; yet every day we read of mass phenomena characterized by numbers in the millions, billions, even trillions. Compounding this challenge is our sense of insignificance as individuals in a world of 6.7 billion people. And if we fully open ourselves to the horrors of our times, we also risk becoming overwhelmed, panicked, or emotionally paralyzed. I believe it is worth connecting with these issues and allowing them to matter to us personally, despite the complex mixtures of anger, fear, grief, and rage that this process can entail.

Perhaps these uncomfortable feelings can become part of what connects us, serving as fuel for courageous individual and collective action as citizens of a new kind of global community. This hope continues to motivate my work.

about the writer

Robin Lasser

Robin Lasser produces photographs, sound, video, site-specific installations and public art dealing with environmental and social justice issues.

Robin Lasser

Floating World: A Tent City Campground For Displaced Human and Bird Song

commissioned by The San Jose Public Art Program

In thinking about imaging the urban wild, a public art installation I created for the city of San Jose, in California, USA springs to mind. I was offered an opportunity to create a public work for the ZERO1 Biennial. The theme of the biennial that year was “make your own world.” The site for this installation is located above an urban cement riverbed and under a busy freeway overpass. I thought, if I am to build my own world, over a river, in the age of climate change, the built environment best be prepared for floods, and take into consideration human needs, as well as the needs of other living creatures in the immediate ecosystem. In collaboration with Marguerite Perrret, we created twenty-one miniature disaster relief tents that are cantilevered off the guardrail gracing the bridge that crosses over the Guadalupe River. The tents are built on stilts; the architecture is designed to protect occupants from the possibility of floods. The tent designs are fashioned after temporary relief shelters, and are scaled for birds. Each tent interior contains a speaker or microphone and lantern. The tents are a conflation of human and bird design elements. They provide sanctuary or shelter for bird and human song, water compositions, and interviews with scientists who speak about the Guadalupe Watershed, birds, flooding, and the relationship of floods to climate change.

The site is at once a habitat and transitionary space; it embodies a river, road, and air that supports migration of humans, birds, and fish. This corridor also references a site for potential displacement of animals and people.

The miniature tents provide sanctuary for bird and human song. The sound is a collage of audio interviews with scientists, environmental educators, urban planners, and kids who love the river. These interviews are mixed with water songs written by locals. The water composition is filtered by precipitation data archived during the most severe floods occurring in San Jose over the past half century.

Birds are changing their tune in order to be heard over local anthropogenic noise. Microphones on site pick up the ambient nose and modify the birdcalls recorded and amplified from speakers in the tent interiors.

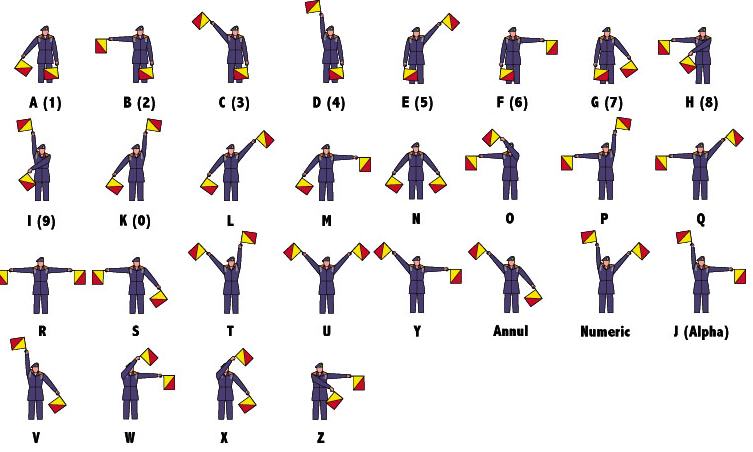

The flags refer to the health, ecology and culture of the river. Patterns on the flags are based on mercury molecules, greenhouse gases, native bird species, and macro invertebrates—all indicators of water quality.

Viewing the video and photo documentation of the Floating World sculpture will help to bring these ideas to life. See it here. My work is also part of the show review elsewhere on TNOC.

about the writer

Monika Lawrence

Monika Lawrence is a German photographer who moved to the US in 2007. She lives in Bemidji, MN where she teaches photography and photojournalism at Bemidji State University.

Monika Lawrence

When we think of “nature”, we have rural areas, nature reserves, or national parks in mind, rather than cities. Why do we often overlook the nature that indeed exists in cities?

More and more wildlife are pulled into new, urban habitats with the decline of natural areas through intensive agriculture, mining, and urban sprawl on the one hand, and enough food and shelter on the other. Moreover, city heat and climate change enable a growing variety of flora and fauna to overwinter in central European latitudes.

Erfurt, the capital of Thuringia, is a city of 200,000 situated in the heart of Germany. It looks back at a history of more than 12 centuries still visible in its medieval inner city; at the same time, it’s a contemporary urban place with modern infrastructure, including a substantial network of public transport and bike trails. More than 50 percent of Erfurt’s population lives in the densely built, relatively small center—a rising tendency as more people seek accessible living environments.

Situated at the transition between the Thuringian basin and the mountain ranges of the Thuringian Forest and the Harz, lots of small streams drain Erfurt’s urban area. Today’s city benefits from several decisions made more than a century ago. A large flood canal (Flutgraben) dug around the old town protects the medieval center from annual flooding. The canal is now a green belt of floodplain forest stretching through the town together with a trail for hikers and bikers. The richness in water bodies provides ideal habitats for insects, frogs, and fish which in turn feed numerous “rural” bird species such as swallows, herons, ducks, or owls. Almost 30 medieval church towers dominate the old town’s silhouette, most with winged inhabitants like falcons or kestrels. Steeples substitute for natural cliffs, including thermal winds for bold flight maneuvers and nesting niches in safe heights. Park landscapes also serve as foraging and hunting areas. Erfurt’s greenspace investments of past centuries are especially important to maintain today, with growing pressures on natural environments elsewhere.

A convergence of needs—human and nonhuman alike—is possible, and in the past 25 years, both Erfurt’s people and its municipal authorities have become more involved in conserving and creating green space. Urban fallows were opened for temporary green space (Zwischennutzung), including an oasis reclaimed from industrial land now used as a community garden. Housing projects densely built at the periphery of the town in socialist times were partially dismantled, opening new spaces, and in the inner city, a planned shopping center had to give way for greenspace with a playground after citizens’ protests. Long-neglected front gardens have been revived, façade greening is getting more popular, newly planted trees give bare streets a fresh look, and competitions for the most beautiful balcony greenings trigger creativity. “Side effects” include a more beautiful city, raised identification with the town, a healthier climate for a city once with quite poor air quality, and more local recreational opportunities. In other words: quality of life.

The inspiration for my photo project came from a course about urban biodiversity my husband Mark gave as a guest lecturer at the University of Applied Sciences Erfurt in 2012. Exploring the urban nature of Erfurt with my camera gave me a whole new perspective on this town where I had been living and working for more than 20 years before I moved to Bemidji, a small town in Minnesota.

Project in progress. See also: www.monika-lawrence.com/urban-nature

about the writer

Patrick M. Lydon

Patrick M. Lydon is an American ecological writer and artist based in Korea whose seeks to re-connect cities and their inhabitants with nature. He writes The Possible City series, is co-founder of City as Nature (Daejeon). He is an Arts Editor here at The Nature of Cities.

Patrick Lydon

unconventional dialogues at the intersection of culture and ecology

In a quest to live ecologically

a man seeks to know nature

in different ways

To know a tree as he knows a good friend

living, growing, sensing

renders betrayal of the tree improbable

Can we meet a tree

as we would another human?

Well, of course

we can

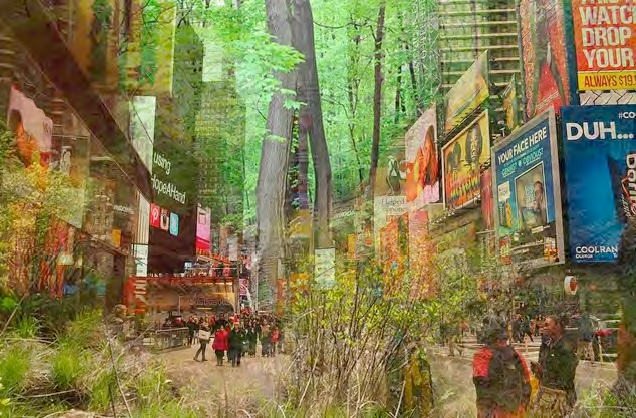

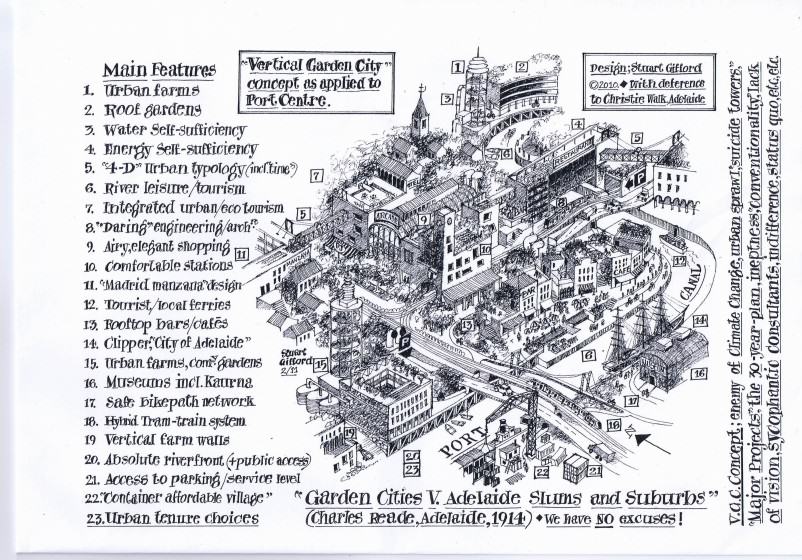

“Centre for Endless Growth”

Building a space for reflection on nature and contemporary culture, Edinburgh, UK

Inspired by dubious proceedings at the World Forum on Natural Capital in Edinburgh, the Center for Endless Growth exhibition offered a public meeting and workspace for catalyzing new ways of thinking about growth, hinting not so quietly that our current methodologies in research and development for economic growth could benefit from direct awareness of ‘real’ growth.

A forest in an office seemed like the appropriate solution. Visitors came in and out during the week, holding meetings and events, and leaving their ideas for a more ecologically just future.

“What is Food: Burger and Cabbage”. Questioning roles in consumption and production, Edinburgh, UK / Berkeley, USA

A living sculpture, What is Food, was created with the help of Vero Alanis and installed in TENT Gallery in Edinburgh, Scotland. It pairs a food which takes very little energy to produce (the cabbage) with one of the most energy-hungry foods (the fast food cheeseburger).

In this role-reversal of sorts, the cabbage slowly feeds on the energy of the decomposing burger during the course of the gallery exhibition.

An archival print of the work was also recently exhibited and acquired by the David Brower Center in Berkeley, California http://www.browercenter.org/exhibitions/reimagining-progress/press

“Disgeotic”. Seeing and feeling the city as a living organism in its own right. International

Disgeotic is a formal, yet almost surreal, photographic survey of urban nature in major cities around the world.

Not simply a matter of pitting growth against decay, these images—the products of walking, lying down, and sitting in cities alone, sometimes for days on end—emote something of the continuous and ever-changing flow of relationships between nature and structure.

This project will extend to include artist-led walking tours this summer in Japan as part of my work for the Robert Callender International Residency for Young Artists.

For more visit: www.pmlydon.com

about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David's dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to "fall back on". So he bought a tuba.

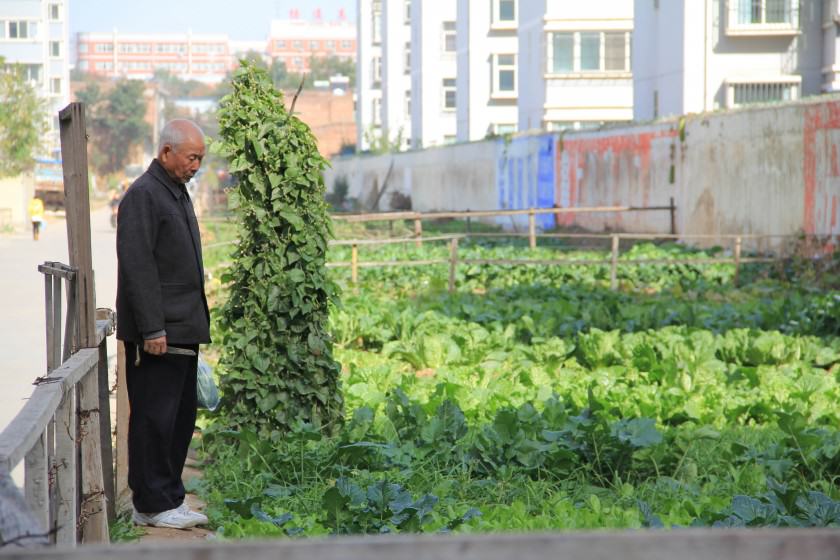

David Maddox

Often, and especially in places like Europe and North America—and in media such as The Nature of Cities—we talk of urban nature in the context of emotional benefits: beauty, biophilia, peacefulness. Another context is one of sustenance and work. One form of this work takes the form of agriculture, food, and harvest. In many regions of the world, we are divorced—physically and psychically—from the work of food, the work of nature and its role in human survival. We go to the grocery store, we buy food. Sometimes we go to farmers’ markets. One of the most vivid intersections of the natural and urban world is at markets. When I travel, key destinations for me are markets and areas of natural harvest—places in cities where people still make their living from the land. In any such a collection of images from markets and nature-work in cities there is certainly beauty, and bounty, and color—nature’s gifts in abundance. There is also back-straining work, and the risks of weather and poor harvests and uncertain incomes. Although all these images come from India, they are scenes repeated around the world, from Andean or Amazonian markets to early morning truck unloading at the Union Square Greenmarket in New York City.

about the writer

Chris Payne

Christopher Payne specializes in the documentation of America’s vanishing architecture and industrial landscape. Trained as an architect, he is the author of several books: New York’s Forgotten Substations: The Power Behind the Subway, Asylum: Inside the Closed World of State Mental Hospitals, and North Brother Island: The Last Unknown Place in New York City.

Christopher Payne

North Brother Island

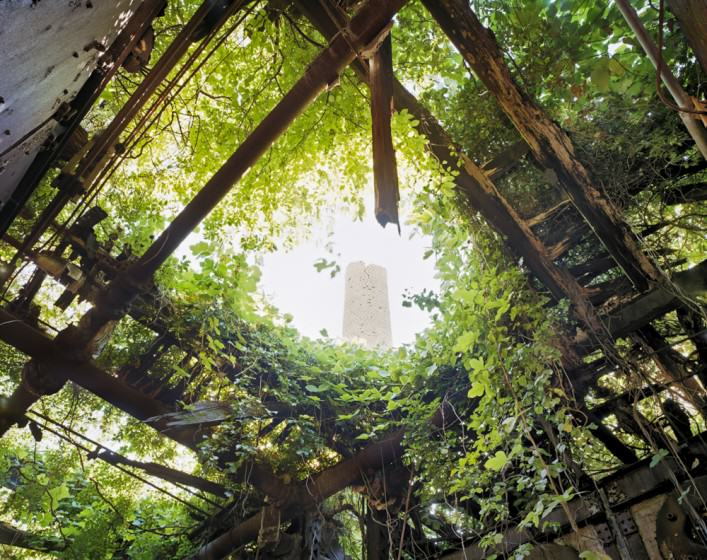

North Brother Island is among the most unexpected of places: an uninhabited island of ruins in New York City that hardly anyone knows; a secret existing in plain sight. Abandoned since 1963, the island was once home to a quarantine hospital and the final residence of Typhoid Mary. Today, it is a wildlife sanctuary closed to the public, but in 2008, I was granted official permission by the New York City Parks Department to take pictures.

I visited North Brother many times between 2008 and 2013, and each time I stepped off the boat I felt as if I had closed my eyes for a few minutes and awakened to find myself in another world, completely alone in the middle of a city. I could not have been happier. In just a few decades, a forest has sprung up where there had once been paved streets, sidewalks, and manicured lawns. If not for the decaying structures, one would never know this place had ever been anything else.

One question that kept nagging me was whether my pictures offered a deeper meaning, beyond their aesthetic appeal and documentary value. Their relationship to New York City and its history was strong, almost overwhelming. Could this small island be viewed in any other context? Did the boundaries of the project extend beyond the geography of the island and the city? Interpreting the ruins as metaphors for the transience of humanity seemed obvious, well-trodden territory. But what if these ruins were embodiments of the future and not just the past? What if all humankind suddenly vanished from the earth? This was the theory proposed by Alan Weisman in his fascinating book, The World Without Us, and it liberated my imagination. The collapse of New York City and its return to a natural state had already happened on North Brother, and Weisman’s words could well have been captions for my photographs. I thought I had found the affirmation I was looking for: a way to connect my pictures to a universal story, one that looks into the future and deals with the conundrum of our living in a natural world that we try to alter, but that always reasserts itself in the end.

about the writer

Eric Sanderson

Eric Sanderson is a Senior Conservation Ecologist at the Wildlife Conservation Society, and the author of Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City.

Eric Sanderson

Manahatta c. 1609. One way to frame the nature of cities is the nature that was there before the city was. This image shows a reconstruction of Manhattan Island at the moment of European discovery in September 1609. The moment is not important, but this snapshot of nature of that moment is important, because it illustrates why cities end up where they do. Cities are not randomly distributed in nature. Rather they tend to show up in places with good soils for growing food, reliable freshwater supplies, at defensible and well-connected places suitable for trade. Mannahatta, as the Lenape Native Americans knew it; New Amsterdam as the Dutch settlers would call it; and New York City as the English and Americans like to call it, exemplifies all of these geographic exigencies of cities. Manhattan had ok soils, but not exemplary soils. (Much better farmland was found in adjacent Queens and Brooklyn, and across the harbor, in Staten Island.) Manhattan did have over 66 miles of streams and 21 ponds and over 300 springs, including a 70 foot deep freshwater pond, the “Collect Pond”, a 20-minute walk from the tip of the island. That tip of a long, wooded island, where the city was founded in 1626, was surrounded by water on three sides, and hills and the pond behind, making it defensible. And the harbor waters, deep enough to float ocean-going vessels practically up to the shore, also connected to a flooded, north-south running fjord, the Hudson River, that ran a hundred miles inland. When the Hudson-Mohawk River systems were connected to the American Midwest by the Eire Canal in 1825, they turned New York City into the greatest mercantile city the world as ever seen.

A Hawks-eye View of the Hudson River, c. 1609. Another advantage of a historical perspective on the nature of cities is that the past sometimes better reveals the nature of cities than the present can. Here, we imagined flying with a kettle of hawks south along the line of the Hudson River. Mannahatta (AKA Manhattan Island) is on the left; and “New Jersey” on the right. The hawk might been a broad-winged hawk or a kestrel or a bald eagle, peering down at the river, where fish such as Atlantic sturgeon, or American shad, or striped bass, were running out to sea. In the distance, a classic “V” of geese travel south. Mannahatta then, like Manhattan today, is a crossroads of migration. It is no wonder that the Statue of Liberty stands over New York harbor or Ellis Island, landing point for the ancestors of millions of Americans, are also located here. New York City is also at a climatic crossroads. The day-to-day weather of the city is highly variable, as it receives storms that travel across the continent from the West, weather tracking up the Atlantic seaboard from the south, and storm systems descending overland from the north. And of course the Hudson River estuary, where the river waters and ocean waters mix, is subject to changes in global sea level. Since the time Henry Hudson sailed into these waters, the ocean has come up about nine-tenths of a foot per century, accelerating more in the 20th and early 21st centuries.

Henry Hudson the day after, c. 1609. What was Henry Hudson thinking the day after he sailed into what would someday be New York harbor? Here, we try to imagine that moment. Henry Hudson was possessed with the idea of opening up a northern trade route from Europe to China. He made four voyages during his life. The first two tried the Northeast Passage around Norway and Russia. Both times he was turned back by ice. On his third voyage, he was again instructed to go northeast, but having hit the ice again, he turned his ship around and sailed for America. Alighting on the coast near the English Jamestown colony in 1609, he started on a careful coastal route to the north, exploring the mouth of Delaware Bay, and eventually coming into New York harbor. Seeing the magnificent river, he thought perhaps he had found his way north, through a tidal strait, to riches and fame in the Orient. Instead, the river petered out around modern Albany, New York; Hudson would return disappointed to Europe. On his final journey, in 1610, he made it into the Bay that bears his name, where his crew mutinied, leaving Henry, his son, John, and a few loyal crewmen in a small boat to wait out the winter. They were never heard from again.

We know what happened now, because it is all ancient history, but at this moment, Henry Hudson had no idea what is fate would be. It is easy to imagine he was elated, buoyed by the possibilities of his future. We imagine him standing on the deck of the Halve Maen (“Half Moon”), watching the sun rise over Manhattan Island. Perhaps one of his men discharges a musket, scaring a flock of thousand passenger pigeons into the morning light. The day brims with rising warmth and possibility.

Of course, in that that moment, Hudson missed what was important for the future. His mind was all about tea-cups and trade goods. For us now, in Henry Hudson’s future, we have more teacups and other things from China than we know what do with. What we miss is the nature that Hudson took for granted, that was right in front of him. Nowhere in the world today, no national park, no nature preserve or wilderness, holds the kind of nature that Manhattan had that morning, nature with all its parts and with all its functions, including people as part and parcel of the whole.

We created this image because we feel that every day is full of warmth and possibility. What will we use it for? Will we make the Hudsonian mistake of taking nature for granted? Or we will dedicate ourselves to granting back to nature warmth and possibility in the cities where we live?

about the writer

Jonathan Stenvall

I’m a photographer born 1997 and based in Stockholm, Sweden. Right now I’m working on a book project about the urban nature and environment in the Stockholm region. You can read more about the project here

Jonathan Stenvall

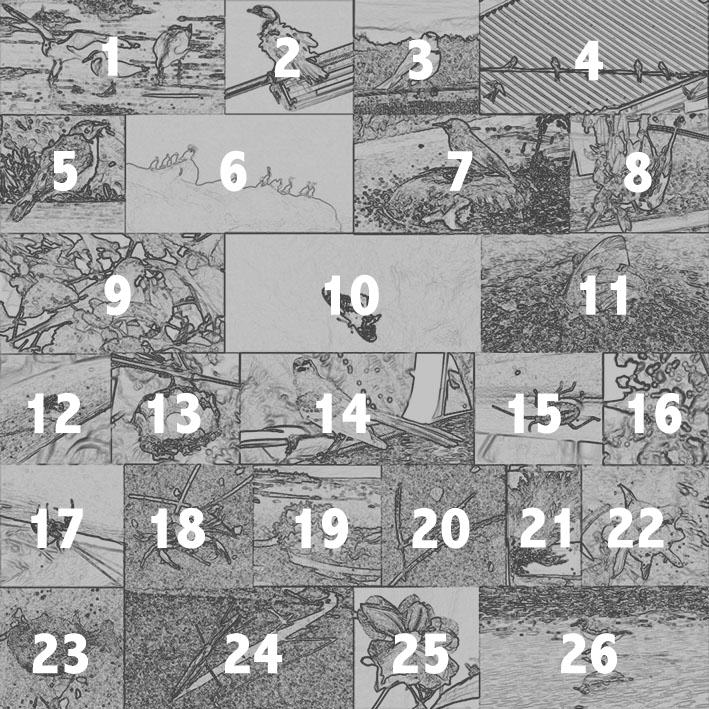

My project started in the spring 2014; during that spring, I was awarded one of the Hasselblads Foundation’s stipends in nature photography for my project about the urban nature in Stockholm. This project aims to conclude in a book that will show the wildlife outside our doorstep—not only the big amount of species that have adapted to live among us, but also the species that are dependent on the valuable green areas that exists in Stockholm and that are, in some cases, also threatened.

One of these areas is the lake Råstasjön. Råstasjön is a big part of the project mainly because it is threatened by plans to construct high-rise buildings around the lake, which will destroy valuable parts of nature. Råstasjön is a unique lake because of its urban location, just 6 kilometers from central Stockholm and right behind Sweden’s new national ”Friends arena”. Because of its urban surroundings, Råstasjön is visited by thousands of people every week, from bird watchers to joggers, schools, and kindergartens. All sorts of people travel to Råstasjön to enjoy the wonderful nature that is located in the middle of Stockholm and easy to reach by train, subway, or bus.

Råstasjön also has about 60 nesting bird species. It is one of the best examples of urban nature in Stockholm, with high biodiversity. At the same time, Råstasjön’s urban location opens it up for everybody to see. What makes me worried is that if the construction companies can get permission to build around this lake, one of the most valuable ones in Stockholm, then what stops them from getting building permissions at any other urban lakes in Stockholm and in the rest of Sweden?

With my pictures and this project, I want to show how valuable and how wonderful the nature we get so close to our homes is. I also hope to show that nature with high biodiversity is possible in the middle of the cities, which is why we have to protect it—not only for the large number of animals, birds and plants, but also for our own sake.

about the writer

Benjamin Swett

Benjamin Swett is a New York-based writer and photographer with a particular interest in combining photographs with text. His books include New York City of Trees (2013), The Hudson Valley: A Cultural Guide (2009), Route 22 (2007), and Great Trees of New York City: A Guide (2000).

Benjamin Swett

New York City contains an estimated 5.2 million trees, which might seem like a lot until you realize that the city also has nearly 8.5 million people. Trees in places such as New York exist in relation to the people and grow, in a sense, at the people’s whim. Much has been written about how trees improve the quality of life in cities by cooling and filtering the air, absorbing excess rainwater, and making neighborhoods more attractive. Less has been said about how they act as storehouses of a city’s past.

In one sense, trees function as living archives, physically storing bits of information about the world around them in their annual growth layers. When studied by dendrochronologists, these layers reveal useful information about the amounts and ratios of sunlight, water, and carbon that reach a tree during a given year. Looked at together, the layers form a pattern that tells a story about the world the tree has experienced during its lifetime. For humans, such records have been valuable in understanding the natural histories of places, and for urban historians in particular, of neighborhoods and cities.

In another way, though, because the lifespans of trees are often so much longer than those of the people who live nearby, and because trees so often assume unusual forms in response to the shapes of the places where they grow, certain trees become focal points for neighborhoods and gather personal associations for the people who live near them or see them every day. It is as if the trees are both part of the urban architecture and separate from it, living things that follow their own organic patterns and change by the seasons and by what goes on around them rather than by the human clock. People develop highly personal emotional connections to these living pieces of architecture and sometimes are not even aware of these connections until the tree is gone. Then suddenly a hole is seen, as if not so much a tree as part of one’s life is missing. If you think of the number of people who live in or regularly pass through different parts of the city, you can begin to picture the number of associations that can develop around a tree that grows there, and the number of people who will be affected if it is gone. This is another kind of history that urban trees carry with them, the history of the many lives that have intersected with them and of the many associations that have gathered around them.

In my work as a photographer of New York City’s trees, I have tried to show the trees as living objects around which such associations may have gathered, and to think about what the places where they grow would be like if they were gone.

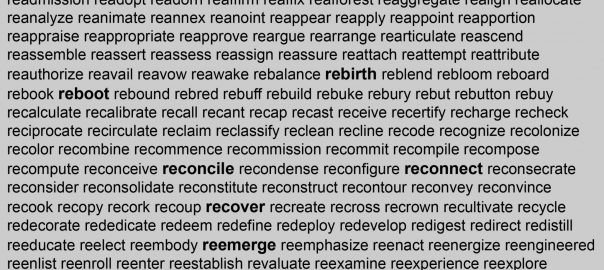

This PAS Report, in line with the current principles of sustainability, discusses green infrastructure (GI) as the visible expression of natural and human ecosystem processes that work across scales and contexts to provide multiple benefits for people and their environments. Unlike other approaches that envision green infrastructure from the standpoint of social infrastructure (e.g., by building capacity in improved health, job opportunities, community cohesion, etc.), this report addresses it first within the matrix or context of hard infrastructure.

This PAS Report, in line with the current principles of sustainability, discusses green infrastructure (GI) as the visible expression of natural and human ecosystem processes that work across scales and contexts to provide multiple benefits for people and their environments. Unlike other approaches that envision green infrastructure from the standpoint of social infrastructure (e.g., by building capacity in improved health, job opportunities, community cohesion, etc.), this report addresses it first within the matrix or context of hard infrastructure.

In my

In my

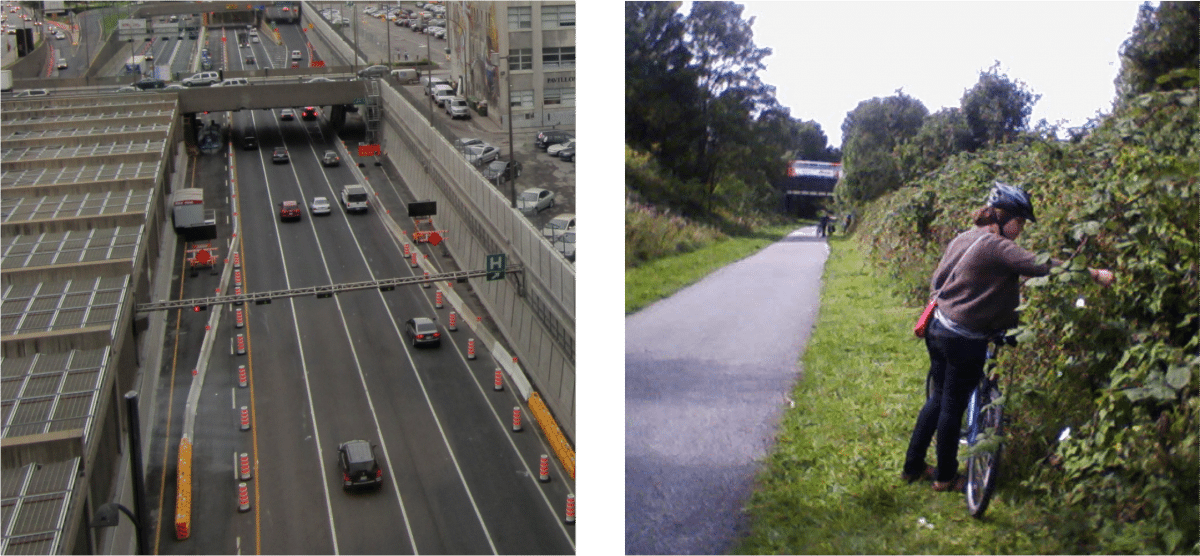

However, in the last century, the situation has changed. These wetlands became a private property where their profitability prevailed over the common good. Changes in technology and economic conditions, coupled with the loss of social control, allowed the growth of the city beyond its limits. The filling and draining of wetlands through engineering has tried to hide the true nature of the city for decades.

However, in the last century, the situation has changed. These wetlands became a private property where their profitability prevailed over the common good. Changes in technology and economic conditions, coupled with the loss of social control, allowed the growth of the city beyond its limits. The filling and draining of wetlands through engineering has tried to hide the true nature of the city for decades.

4 Comments

Join our conversation