The food system refers to processes that begin with agricultural production and continues with the processing, packaging and transport that is the result of food industrialization. This industrialization started with the improvements to agricultural production during the 20th century, the so-called “green revolution”. They led to an increase in crop yields and reduction in manpower, which has resulted in the massive abandonment of the countryside and fueled in part the migration to the cities.

The industrialization of agriculture also began the process of territorial segregation between food-growing areas and urban settlements, along with a high consumption of fossil fuels, from the manufacture of fertilizers and pesticides to all phases of production: planting, irrigation, harvesting, distribution and packing. This food production system, not only supplies food for city dwellers, but also contributes to several environmental impacts, including climate change. Thus, everyday eating habits have strong relationships to environment degradation.

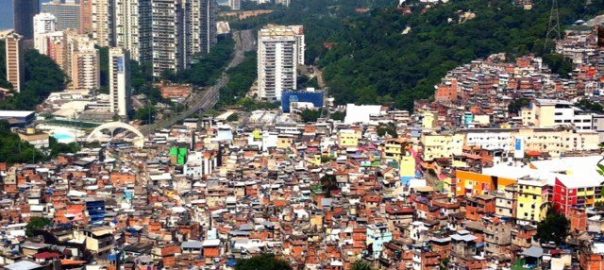

On the other hand, the world urban population has been growing during the last century, and since 2008, for the first time in history of humanity, more than a half the world’s population lives in cities. Basically, almost all of the coming decades’ population growth will be urban, and if the current tendency toward the growth of cities continues, 70-80 percent of global population is expected to live in world’s cities by 2050, we get an idea of how important one of the urban challenges is: how to feed this growing urban growing population with the least environmental impact.

Urban food environmental impact

Something as mundane as nutritional habits may have a relationship to environment degradation. What we choose to eat is responsible for more or less impact in two fundamental ways. First, food production and transportation depends on fossil fuels. The second depends on how many animal products are consumed. These food factors have diverse environmental impacts, but also, in the case of the industrial food system, has had regional (territorial)consequences in how urban space is organized, due to segregation of food growing areas from urban settlements. This functional specialization, first at a territorial level, and later at a global level, sustained by increased reliance on fossil fuel has compounded the environmental impacts of the urban food system, such as climate change, but there are also other environmental impacts.

Urban food systems, are responsible for large environmental impacts, involving erosion, deforestation, water and soil pollution, etc. But this essay is focused fundamentally on the environmental impacts from a point of view of the resource consumption needed to feed cities—energy, water and land; and consequences like climate change, and deforestation.

The conventional urban model, from an urban ecology point of view is unproductive; It doesn’t generate any resources needed to function. That is why cities are highly dependent on a global transport network, and consequently are tied to continuous fossil fuels consumption, being always affected by fuel availability and price.

But climate change is only one side of the food impact; food production also has an impact on how much water is consumed, and how much land is deforested.

The energy utilized in the global food system includes the energy used in the production of food-stuffs, the manufacture of fertilizers and pesticides, irrigation and the activities of postproduction—processing, packaging and transport, storage and sales—which involves a higher consumption of fossil fuels, and consequently CO2 emissions, greenhouse emissions responsible for climate change. The food chain reveals the importance of indirect consumption of fossil fuels on food—about 6 lbs/per capita a day (Carpentero, 2005)—related to industrial agriculture,

Usually, the carbon gas from fossil fuel combustion has been the center of attention for climate change prevention strategies, and other sources are forgotten. If the food system is analyzed without fossil fuels, agricultural production causes greenhouse gas emissions, directly and indirectly in different ways: By changing land use, deforesting forest areas and transforming them into agricultural land; and by livestock methane emission.

Nearly three-quarters of deforestation and degradation can be attributed to agriculture, including crop production and cattle. The reason why deforestation is related to climate is that when trees are clear-cut they release the carbon they are storing into the atmosphere, and this contributes to global warming. So climate change mitigation strategies should be doing as much as possible to prevent deforestation caused by agriculture, as well as encouraging energy efficiency and reduced transport.

In the case of methane emissions, according to the United Nations (UN), agriculture is responsible for producing more greenhouse gas emissions annually than all worldwide transportation. In fact a World Watch report states that livestock causes 51 percent of all greenhouses gas emissions. But, how could that be? Methane, the gas emitted by cattle, has a global warming potential about 84-87 times the warming effect of CO2 in twenty years, (according to US Environmental Protection Agency’s inventory of greenhouse gas emissions). This means that the meat and dairy industries have a huge impact on climate change, and urban diet habits trend toward a higher consumption of meat according to Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN.

On the other hand, the effects of climate change on urban food security are another challenge that can lead to a scarcity of foodstuffs. Water is essential for agricultural production, and climate change is especially altering rain patterns. This has become an urban food vulnerability based on a conventional urban food system, characterized by the spread production territory all over the world. Food has so many chains and distances to travel that makes it more difficult to control.

In climate change mitigation and resilience strategies diverse knowledge of direct and indirect urban emissions are required. But mitigation plans are likely to be centered mostly on urban CO2 emissions by transport and mobility; in the meantime urban food’s CO2 and methane could have a largest effect on climate change.

Water consumption

Urban sustainability means reducing resource consumption, including water. Urban water policies address reducing household and commercial consumption. Urban food demand on water indirectly affects urban water consumption, and it should counts toward the urban water footprint, but it is often forgotten.

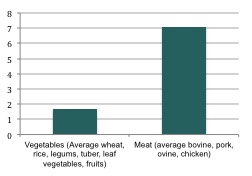

The fact is that water is required to produce food. This cannot be changed. But the important aspect to be noticed is that the water requirement to produce meat is huge as compared to the requirement to produce vegetables.

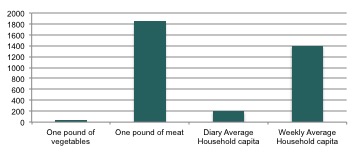

According to Water Footprint Network, to produce 1 pound of vegetables, 38 gallons (322 lts/kg) of water are needed, meanwhile, to produce 1 pound of meat, the demand of water is about 1850 gallons of water (7004 lts/kg), 48 times more water to produce meat than vegetables.

Land occupancy

Urban space for city development, includes not only the physical surface occupied by the city’s administrative limits; but also, all the territory employed to produce the resources the city needs. The agricultural land for human feed, and agricultural land for animal forage to produce human feed, should indirectly be considered a functional part of a city. Agricultural production to feed a city is costly in terms of ecosystem impacts, particularly in terms of deforestation.

The amount of land required for agricultural production is directly related to diet. Increasingly, animals raised for food are been feeding less on pasture and more with grains and fodder crops. Consequently a diet based on a high consumption of meat requires at least three times more agricultural land than vegetarian diet. The impact of this choice is so large that, according to Carpintero, given the actual global population and the land, energy and water demands for meat production, it is not Possible to feed humanity with a high animal protein diet.

Urban land demand related to food production, runs counter to the desire for sustainable control of urban land expansion. However, urban sustainable growth should include both limits on the extension of urban boundaries, and control overexpansion of agricultural land for urban feeding.

Urban agriculture and city sustainability

Food for cities is supplied by an urban agro-alimentary system; the improvement of this system could have a positive impact on urban sustainability. Potential improvements include employing different strategies, such as bringing agricultural production closer to urban areas, and changing urban diet to reduce meat consumption. This means decreasing the city dependence on distant agro-system territories spread all over the world that form a fuel dependent global food network. In its place, a regional food agro-system must be developed, so production, distribution and consumption are not distant from each other. In that food system, urban and peri-urban vegetable agriculture would play a fundamental part. However in order to make this shift in food production, urban planning must change its urban food system, and consequently the basic urban model. In order to achieve urban agricultural development that is neither incidental nor isolated, it should be integrated into urban and territorial planning, and to land use. Doing so would foster relationships, not only between urban agricultural production and the city, but would also foster ecological, social and economic relations.

The benefits of this strategy are enormous, not only reducing greenhouses emissions by minimizing food transport, but also by reducing packaging and refrigeration. This means less urban waste and less energy consumption. Also urban and peri-urban agricultural production would take place on previously disturbed land, reducing deforestation of natural areas. , However, this benefit would be increased only if urban diet also reduces meat consumption. In that sense, the city should develop strong social campaigns to persuade citizens to reduce their meat intake, including meat taxes that are related to its environmental impact (climate change, deforestation and water consumption).

On the other hand, urban food vulnerability to the effects of climate change could be reduced with near agricultural production. Food security and adaptation to climate change have a close mutual relationship. The principle of proximity, bringing food production physically close to consumers, takes on a greater importance as a strategy of adaptation, because food availability may become an issue due to transport limitations when climate conditions are difficult. Also by bypassing the chain of fossil fuel consumption, CO2 emissions are reduced, and the price of urban green vegetables stabilizes as they are no longer dependent on a fluctuating fuel prices. Urban food production could supply vegetables that might otherwise be in short supply because of climate change driven drought conditions at remote agricultural lands. Treated urban wastewater can only irrigate agricultural land if it is close to the water source. So urban agricultural production might guarantee food in those difficult weather conditions. Reliance on urban gray water for agricultural production instead of fresh water irrigation could be considered contribution to closing the water cycle.

One important aspect to consider in terms of land use value, is that urban land must be valued not for its real-state potential, but it must be valued for its food security services. However, urban agriculture should be a worthwhile economic activity that could guarantee a long-term return.

But, is it possible for cities to achieve vegetable self-sufficiency?

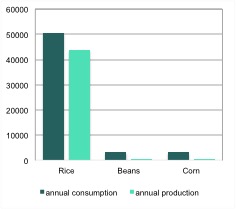

With the appropriate urban land use strategies, urban green system changes, urban/peri-urban production policies, and urban and building redesign, surely it is possible. According to research on Barcelona, by employing a variety of strategies the city could achieve 70 percent vegetable production self-sufficiency (Arosemena, 2008) . In Panama City traditionally, agriculture production takes place in peri urban areas, principally rice production. Until 2013 Panama City had the potential to be 86 percent self-sufficient in rice production. It was also estimated to be 12 percent self-sufficient in corn production and 6 percent in beans. While the example of Panama City is not planned peri-urban agriculture these numbers show how urban agricultural self-sufficiency is a possibility. And also to keep in mind that productive potential can also be reduced by urban development pressure.

Conclusions

Every city that expects to be sustainable must take into account all its environmental externalities, and mitigate them as much as possible by reducing the need to exploit other territories and ecosystems in order to achieve the resources city requires to function.

But urban feeding and its associated environmental consequences are usually forgotten when planning for sustainability. In this task, the evaluation of food system environmental impacts involved the consideration of multiple factors, including urban water consumption, land use and deforestation, and climate change. By understanding and accounting for the environmental externalities associated with remote urban food production, and encouraging more local production through changes in urban planning and policies, and encouraging a change in dietary habits to reduce meat consumption, cities can move toward authentic food sustainability. In doing so, the city gets certain degree of self-sufficiency, and in terms of urban food, begins to develop urban/peri-urban agriculture and ultimately a new urban food system.

Until urban planners begin to internalize and address the organization of city food systems, we cannot talk about a complete urban sustainability.

Graciela Arosemena

Panama City

References

Arosemena, Graciela. (2008) . Ruralizar la ciudad: Metodología de introducción de la agricultura como vector de sostenibilidad en la planificación urbana. Tesis doctoral. Universidad Politécnica de Cataluña. Barcelona.

Arosemena, Graciela. (2012). Urban agricultura: Spaces of cultivation for a sustainable city. Gustavo Gili. Barcelona.

Carpintero, Oscar. (2005) El metabolismo de la economía española. Recursos naturales y huella ecológica (1955-2000). Economía Vs. Naturaleza. Fundación César Manrique. España.

U.S Geological Survey. Science for a changing world. https://www.usgs.gov

Water Footprint Network. www.waterfootprint.org

Speaking a common language: using a voice that engages and inspires

Speaking a common language: using a voice that engages and inspires

Target 1: “By 2020, at the latest, people are aware of the values of biodiversity and the steps they can take to conserve and use it sustainably.”

Target 1: “By 2020, at the latest, people are aware of the values of biodiversity and the steps they can take to conserve and use it sustainably.”  Target 2: “By 2020, at the latest, biodiversity values have been integrated into national and local development and poverty reduction strategies and planning processes and are being incorporated into national accounting, as appropriate, and reporting systems.

Target 2: “By 2020, at the latest, biodiversity values have been integrated into national and local development and poverty reduction strategies and planning processes and are being incorporated into national accounting, as appropriate, and reporting systems. Target 3: “By 2020, at the latest, incentives, including subsidies, harmful to biodiversity are eliminated, phased out or reformed in order to minimize or avoid negative impacts, and positive incentives for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity are developed and applied, consistent and in harmony with the Convention and other relevant international obligations, taking into account national socio‑economic conditions.”

Target 3: “By 2020, at the latest, incentives, including subsidies, harmful to biodiversity are eliminated, phased out or reformed in order to minimize or avoid negative impacts, and positive incentives for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity are developed and applied, consistent and in harmony with the Convention and other relevant international obligations, taking into account national socio‑economic conditions.” Target 4: By 2020, at the latest, Governments, business and stakeholders at all levels have taken steps to achieve or have implemented plans for sustainable production and consumption and have kept the impacts of use of natural resources well within safe ecological limits.

Target 4: By 2020, at the latest, Governments, business and stakeholders at all levels have taken steps to achieve or have implemented plans for sustainable production and consumption and have kept the impacts of use of natural resources well within safe ecological limits.  Target 5: By 2020, the rate of loss of all natural habitats, including forests, is at least halved and where feasible brought close to zero, and degradation and fragmentation is significantly reduced.

Target 5: By 2020, the rate of loss of all natural habitats, including forests, is at least halved and where feasible brought close to zero, and degradation and fragmentation is significantly reduced. Target 6: By 2020 all fish and invertebrate stocks and aquatic plants are managed and harvested sustainably, legally and applying ecosystem based approaches, so that overfishing is avoided, recovery plans and measures are in place for all depleted species, fisheries have no significant adverse impacts on threatened species and vulnerable ecosystems and the impacts of fisheries on stocks, species and ecosystems are within safe ecological limits.

Target 6: By 2020 all fish and invertebrate stocks and aquatic plants are managed and harvested sustainably, legally and applying ecosystem based approaches, so that overfishing is avoided, recovery plans and measures are in place for all depleted species, fisheries have no significant adverse impacts on threatened species and vulnerable ecosystems and the impacts of fisheries on stocks, species and ecosystems are within safe ecological limits. Target 7: By 2020 areas under agriculture, aquaculture and forestry are managed sustainably, ensuring conservation of biodiversity.

Target 7: By 2020 areas under agriculture, aquaculture and forestry are managed sustainably, ensuring conservation of biodiversity. Target 8: By 2020, pollution, including from excess nutrients, has been brought to levels that are not detrimental to ecosystem function and biodiversity.

Target 8: By 2020, pollution, including from excess nutrients, has been brought to levels that are not detrimental to ecosystem function and biodiversity. Target 9: By 2020, invasive alien species and pathways are identified and prioritized, priority species are controlled or eradicated, and measures are in place to manage pathways to prevent their introduction and establishment.

Target 9: By 2020, invasive alien species and pathways are identified and prioritized, priority species are controlled or eradicated, and measures are in place to manage pathways to prevent their introduction and establishment. Target 10: By 2015, the multiple anthropogenic pressures on coral reefs, and other vulnerable ecosystems impacted by climate change or ocean acidification are minimized, so as to maintain their integrity and functioning.

Target 10: By 2015, the multiple anthropogenic pressures on coral reefs, and other vulnerable ecosystems impacted by climate change or ocean acidification are minimized, so as to maintain their integrity and functioning. Target 11: By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water areas, and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes.

Target 11: By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water areas, and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes. Target 12: By 2020 the extinction of known threatened species has been prevented and their conservation status, particularly of those most in decline, has been improved and sustained.

Target 12: By 2020 the extinction of known threatened species has been prevented and their conservation status, particularly of those most in decline, has been improved and sustained. Target 13: By 2020, the genetic diversity of cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals and of wild relatives, including other socio-economically as well as culturally valuable species, is maintained, and strategies have been developed and implemented for minimizing genetic erosion and safeguarding their genetic diversity.

Target 13: By 2020, the genetic diversity of cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals and of wild relatives, including other socio-economically as well as culturally valuable species, is maintained, and strategies have been developed and implemented for minimizing genetic erosion and safeguarding their genetic diversity.  Target 14: By 2020, ecosystems that provide essential services, including services related to water, and contribute to health, livelihoods and well-being, are restored and safeguarded, taking into account the needs of women, indigenous and local communities, and the poor and vulnerable.

Target 14: By 2020, ecosystems that provide essential services, including services related to water, and contribute to health, livelihoods and well-being, are restored and safeguarded, taking into account the needs of women, indigenous and local communities, and the poor and vulnerable. Target 15: By 2020, ecosystem resilience and the contribution of biodiversity to carbon stocks has been enhanced, through conservation and restoration, including restoration of at least 15 per cent of degraded ecosystems, thereby contributing to climate change mitigation and adaptation and to combating desertification.

Target 15: By 2020, ecosystem resilience and the contribution of biodiversity to carbon stocks has been enhanced, through conservation and restoration, including restoration of at least 15 per cent of degraded ecosystems, thereby contributing to climate change mitigation and adaptation and to combating desertification. Target 16: By 2015, the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization is in force and operational, consistent with national legislation.

Target 16: By 2015, the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization is in force and operational, consistent with national legislation. Target 17: By 2015 each Party has developed, adopted as a policy instrument, and has commenced implementing an effective, participatory and updated national biodiversity strategy and action plan.

Target 17: By 2015 each Party has developed, adopted as a policy instrument, and has commenced implementing an effective, participatory and updated national biodiversity strategy and action plan. Target 18: By 2020, the traditional knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, and their customary use of biological resources, are respected, subject to national legislation and relevant international obligations, and fully integrated and reflected in the implementation of the Convention with the full and effective participation of indigenous and local communities, at all relevant levels.

Target 18: By 2020, the traditional knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, and their customary use of biological resources, are respected, subject to national legislation and relevant international obligations, and fully integrated and reflected in the implementation of the Convention with the full and effective participation of indigenous and local communities, at all relevant levels. Target 19: By 2020, knowledge, the science base and technologies relating to biodiversity, its values, functioning, status and trends, and the consequences of its loss, are improved, widely shared and transferred, and applied.

Target 19: By 2020, knowledge, the science base and technologies relating to biodiversity, its values, functioning, status and trends, and the consequences of its loss, are improved, widely shared and transferred, and applied. Target 20: By 2020, at the latest, the mobilization of financial resources for effectively implementing the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 from all sources, and in accordance with the consolidated and agreed process in the Strategy for Resource Mobilization, should increase substantially from the current levels. This target will be subject to changes contingent to resource needs assessments to be developed and reported by Parties.

Target 20: By 2020, at the latest, the mobilization of financial resources for effectively implementing the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 from all sources, and in accordance with the consolidated and agreed process in the Strategy for Resource Mobilization, should increase substantially from the current levels. This target will be subject to changes contingent to resource needs assessments to be developed and reported by Parties.

My friend Madhu Katti (also a TNOC writer) has written about other invasions of urban habitat by wildlife in recent times, including the return of the

My friend Madhu Katti (also a TNOC writer) has written about other invasions of urban habitat by wildlife in recent times, including the return of the

2 Comments

Join our conversation