The Year 2007 marked the arrival of the Urban Millennium when most of the world’s population became urban for the first time in human history (UNDESA, 2009). The proportion is now at least 55% and the global urban population is predicted to increase by 2.5 billion over the next 30 years (UNDESA, 2019). In North America, South America, and the Caribbean, 80 % of the population reside in urban settlements, while in Europe the proportion is 73% (EU Joint Research Center, 2019).

I recall how many environmentalists reacted with foreboding to this turning point (or tipping-point, as they saw it), as it served to highlight the relentless march of the concrete jungle into rural “paradise”, to paraphrase Joni Mitchel’s lament (Big Yellow Taxi, 1970). Certainly, in many developed nations, the belief that urban growth is the primary driver behind the loss of nature is commonly held by many journalists who echo or stoke the fears of the general public.

Such fears have been heightened by rural campaign bodies such as the Council for the Protection of Rural England, which has set out a particularly J.G. Ballard-inspired dystopian vision for England – “It’s 2035, and the countryside is all but over… there is no longer any distinction between town and country. Town does not end, countryside does not begin” (Kingsnorth, 2005). A similar ominous prediction for England’s green and pleasant land was expressed 30 years earlier by celebrated English poet, Phillip Larkin, in his poem Going, Going – “as the bleak high-risers come … more houses, more parking allowed … Despite all the land left free. For the first time I feel somehow that it isn’t going to last … And that will be England gone”. In academia, too, there seems to be a consensus that urban growth is a very major cause of biodiversity loss (McDonald, et al., 2018), if not the primary driver (McKinney, 2002; Catalano et al., 2021).

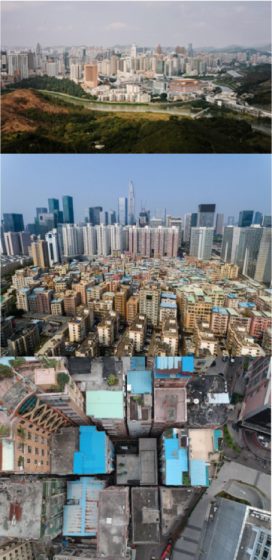

While urbanization certainly has had many very negative impacts on the natural world, is the hostility that environmentalists and the wider public hold for it justified, or is there a much more important factor driving biodiversity loss? As to the first part of the question, a skepticism about the scale of impact has been simmering for many years before being emphatically reemphasized relatively recently by the likes of David Owen and Edward Glaeser in their books Green Metropolis (2011) and Triumph of the City (2012) respectively. Both authors take the contrary viewpoint and contend that well-organized compact urban agglomerations benefitting from economies of scale have much lower environmental footprints than alternative lower-density arrangements of human populations of similar size. Flagship cities for these authors include New York, Hong Kong, and Singapore. Owen does concede, however, that “thinking of crowded cities as environmental role models requires a certain willing suspension of disbelief because most of us have been accustomed to viewing urban centers as ecological calamities”.

As to the second part of the question, while it is repeatedly asserted that Joni Mitchel was heaping the blame squarely on urban expansion for the loss of paradise, an oft-forgotten line of her song also implicates another culprit – “hey farmer, farmer put away that DDT now. Give me spots on my apples, but leave me the birds and the bees”; lyrics inspired by Rachel Carson’s 1962 tour de force, Silent Spring. Indeed, I contend here that it is “our global food system [and not urbanization, which] is the primary driver of biodiversity loss” (Benton et al., 2021).

Debating in a numerical vacuum

Discussions as to whether we are approaching a point where town does not end and countryside does not begin often take place in a numerical vacuum. According to Our World in Data, only 1% of the earth’s land area is built up urban, including cities, towns, villages, roads, and other human infrastructure (Ritchie & Roser, 2019). The figure is 2% in the US (World Economic Forum, 2020), while in the UK, which is a particularly densely populated nation, the figure is 7-8% (Office for National Statistics, 2019). Urban areas also include parks, gardens, golf courses, and many other forms of greenspace, so the actual footprint of concrete and asphalt may be smaller depending on how these numbers were calculated; in the UK ‘natural land cover’ accounts for 31% of urban areas.

Compact-city living

According to McDonald, et al. (2018), urban growth resulted in the loss of 190,000 km2 of natural habitat between 1992-2000 (16% of all natural habitat lost over this period) and threatens an additional 290,000 km2 by 2030. These findings are concerning, but such studies sometimes fail to fully consider the ecological and other environmental benefits of urbanization or consider what the environmental implications would have been had the new urbanites remained in the countryside.

While carbon footprint per unit area is higher in urban than rural areas, this is because there are many more people per unit area. In developed nations, at least, the carbon footprint per capita is lower in urban centers than in rural areas or sprawling suburbs (Owen, 2011; Glaeser, 2012). Residents of urban centers are less inclined to drive because services are readily accessible by foot or public transport. Policies are also in place to constrain car use in cities, e.g., restricted and costly parking charges; limited space to ease congestion through road capacity expansion; and the introduction of congestion charges (e.g., London). Because heat consumption is correlated with floor area and the ratio of wall area to floor area, rural and suburban housing, which is typically larger and detached, also uses more energy than in urban centers where apartments and terraced housing are the norms.

If we were to dismantle major urban centers and spread their populations over the surrounding countryside, far more pastoral paradise would be consumed and carbon footprint per capita would rise dramatically. Moreover, exacerbating climate change would cause additional biodiversity loss (IPCC, 2022).

Are the indirect impacts of urbanization exaggerated?

McDonald, et al. (2018) argue that the external land area needed to provide food, water, and materials to cities should also be taken into account when assessing their environmental footprint. However, in isolation, such analysis is misleading. The populations of urban centers would still need to eat and consume water if they were to be teleported into rural areas, and in developed countries, at least, their footprints would be much higher. This is because there are enormous economies of scale to be derived from supplying food and water to large concentrations of people compared with similar populations widely dispersed across the landscape (Owen, 2011; Monbiot, 2022).

While the need to minimize food miles and the concept of locavorism is music to the ears of many environmentalists, various other factors need to be considered when assessing environmental footprint, including how the food is grown and how it reaches its destination. Because food items are transported in bulk to cities, often with a range of other products, food miles per unit can often be much smaller for produce transported long distances than for the same food item that has been purchased in a local farmer’s market.

Moreover, focusing on food production where growing conditions are most optimal, maximizes production and reduces carbon output per unit. Monbiot (2022) is particularly uncompromising on this point – “given the distribution of the world’s population and the regions suitable for farming, the abandonment of long-distance trade would be a recipe for mass starvation”.

Is vertical farming the solution?

To circumvent the limitations of locavorism, some champion indoor and vertical farming systems (VFS) in cities, i.e., growing crops in vertically stacked layers using soil-less techniques such as hydroponics. However, the economic viability of VFS is currently uncertain, as start-up infrastructure costs are high and the process is labor and energy intensive. VFS, therefore, faces stiff competition from traditional horizontal farms in the countryside that have lower infrastructure and land costs, as well as free sunshine (Owen, 2011; Delden et al., 2021; Moghimi, 2021; Monbiot, 2022). Nevertheless, there still appears to be momentum behind VFS that is attracting investment and so increased efficiencies are anticipated from improved automation. Whether these will be sufficient to establish a profitable sector able to make a reasonably significant contribution to food supplies remains far from clear.

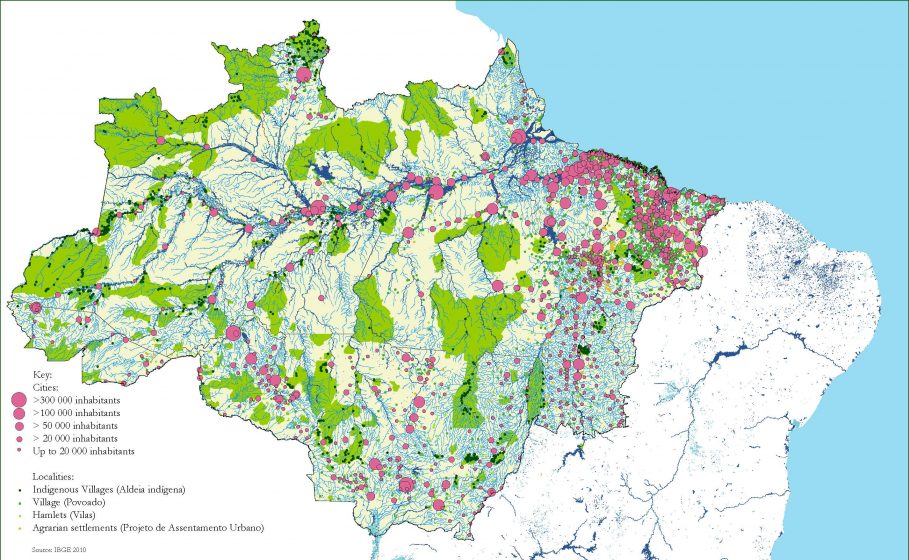

Urbanization in low-income countries

Contrary to the trends in developing nations, urbanization in low-income countries may initially increase emissions per capita, as the newly arrived consume more electricity and transport than their rural counterparts (Li & Lin, 2015; Connolly et al., 2022). While attempts have been made to inhibit urbanization in low-income countries these have largely been ineffective, and arguably, undesirable (Tacoli, 2015; Macdonald, 2016). All developed nations originally transitioned from agrarian to urbanized societies and low-income countries are now going through the same process. Those living comfortable lives in high-income nations should remind themselves that most people migrating to cities in low-income countries are not leaving behind some rural utopia but rather are desperately poor and are seeking a better standard of living for themselves and their families (Pearce, 2010; Glaeser, 2012). Moreover, as low-income countries transition to middle and high-income countries, the per capita environmental footprints of urban residents are likely to fall below those of their rural compatriots.

Owen (2011) suggests that the antipathy so many environmentalists have towards urbanization has a somewhat Malthusian undercurrent. Some commentators seem to imagine that rural-urban migrants would vanish into the ether if only the process could be stopped. However, a growing world population and accompanying urban growth are inevitable. The world population is approaching 8 billion and is projected to peak at approximately 10.4 billion people during the 2080s (UNDESA, 2022).

Contrary to any Malthusian fears, urbanization is and will continue to be an important and environmentally beneficial process in the demographic transition, slowing overall population growth. This is because fertility rates are lower in cities than in rural areas. Women socialized in cities are likely to be better educated, more involved in economic activities outside the household, have improved access to family planning services, are less culturally constrained, and opt to marry at a later age, and for all these reasons and more, choose to have smaller families than those in neighboring rural areas (Lerch, 2019). Therefore, achieving gender equity (in part driven by urbanization) is critical for, inter alia, meeting sustainability goals.

Density done well

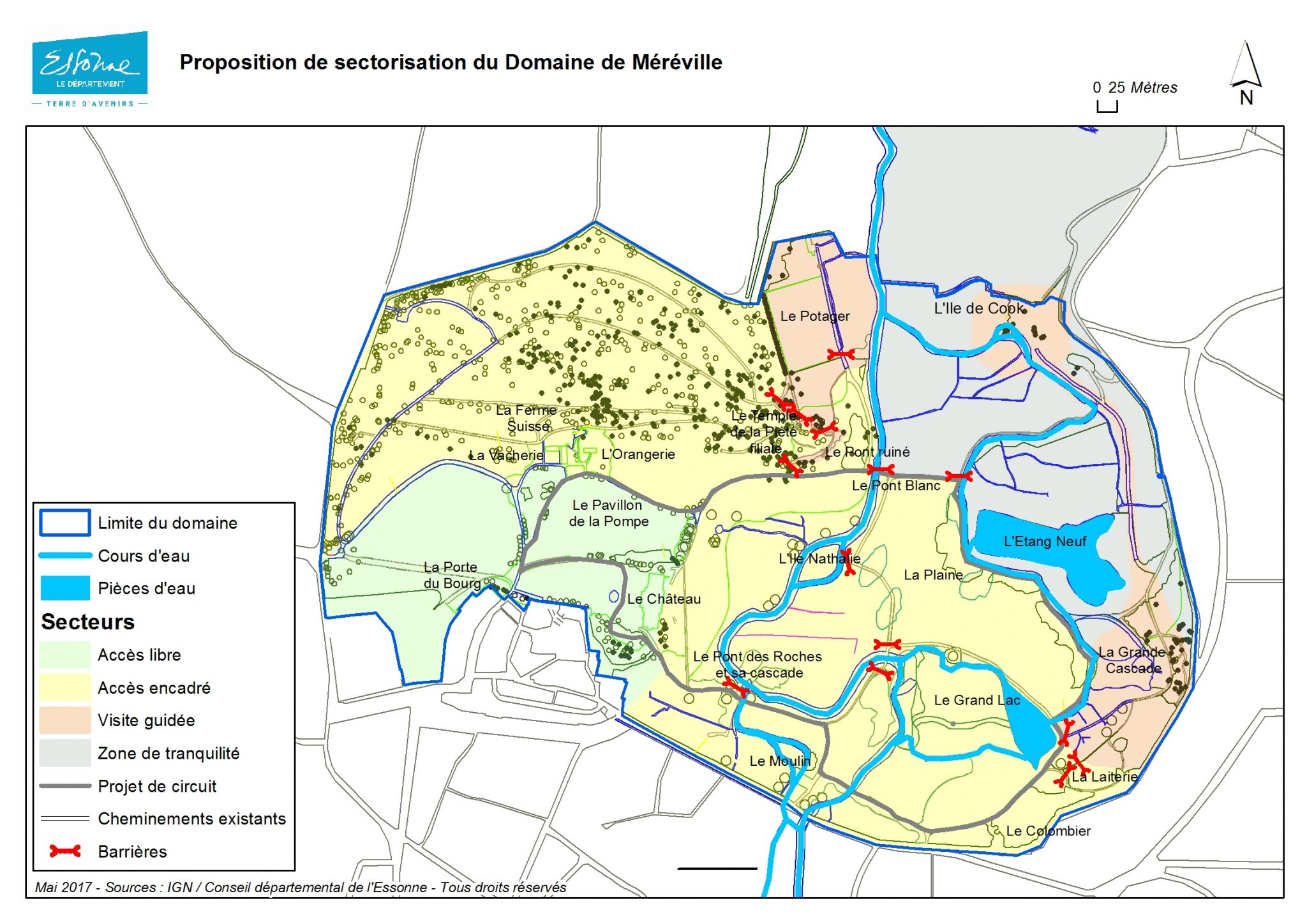

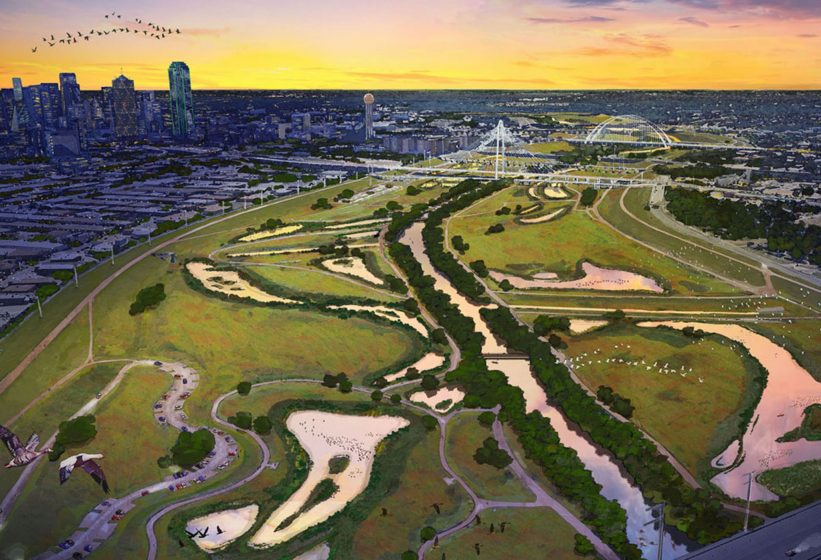

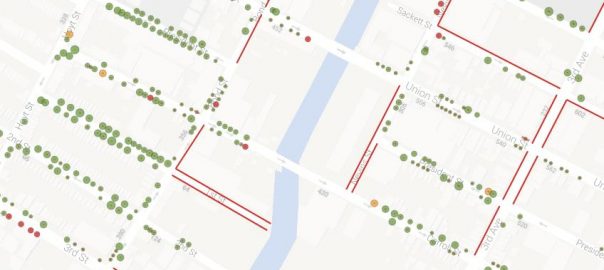

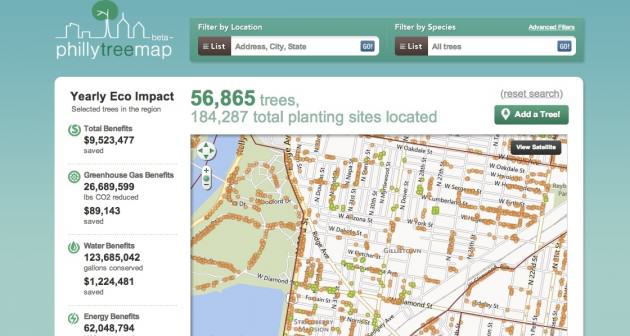

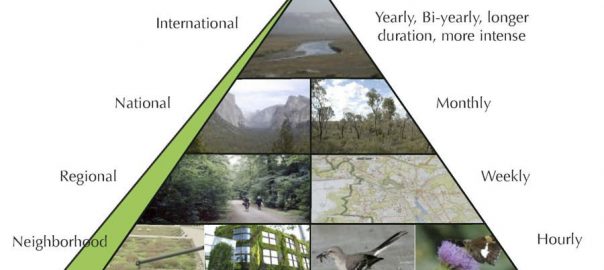

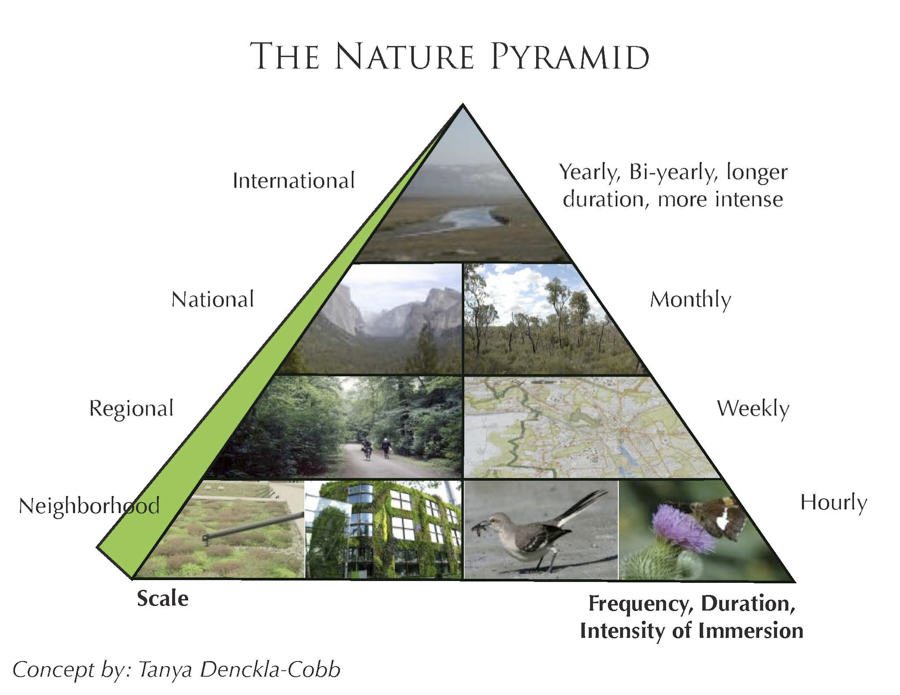

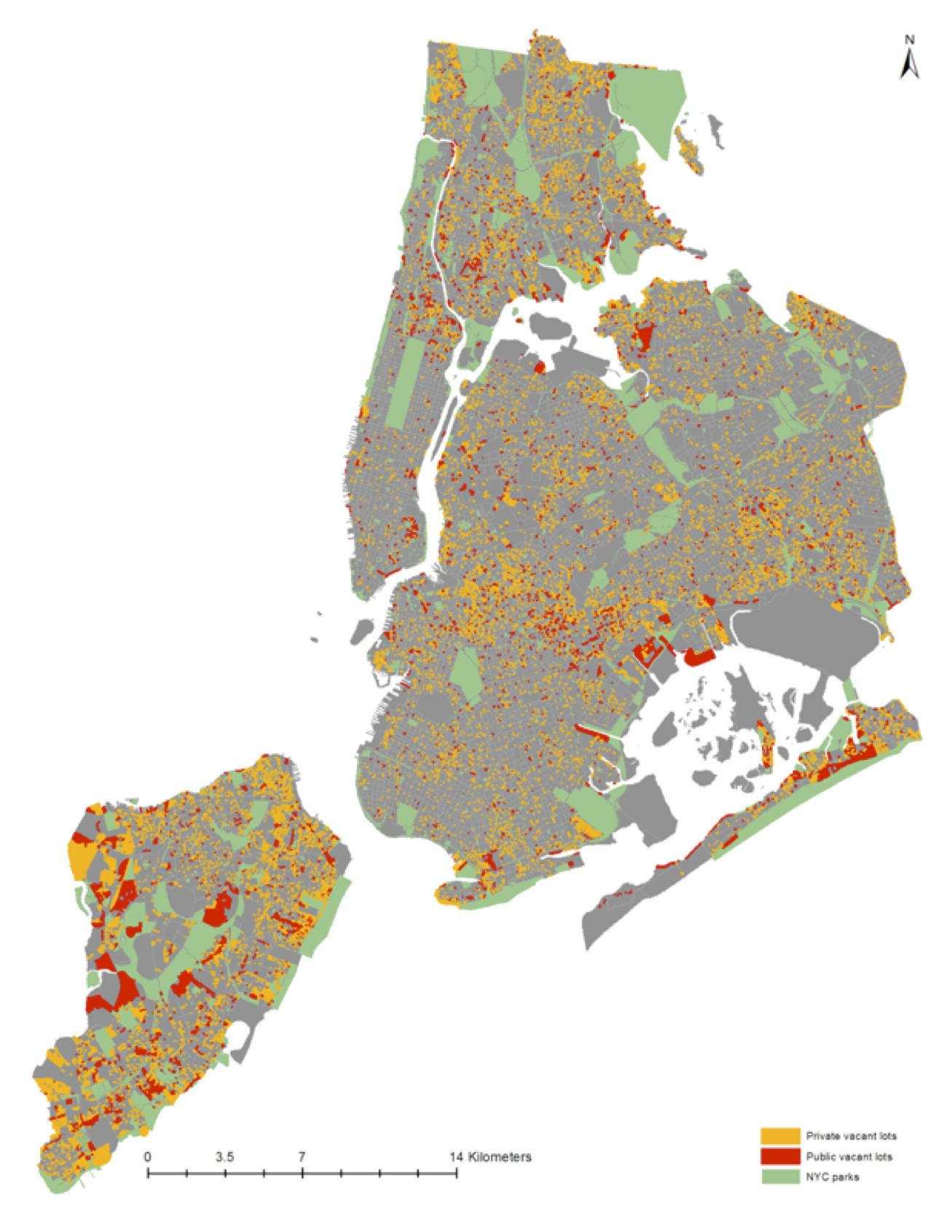

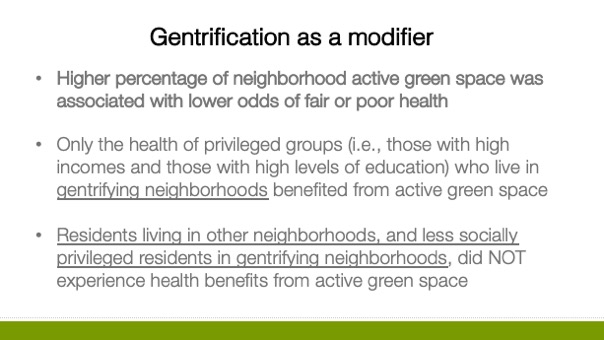

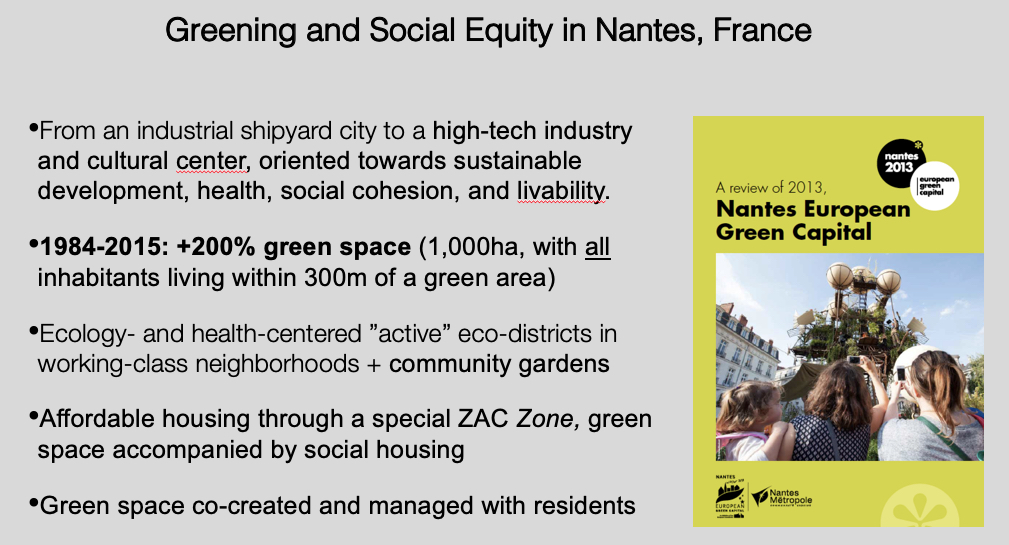

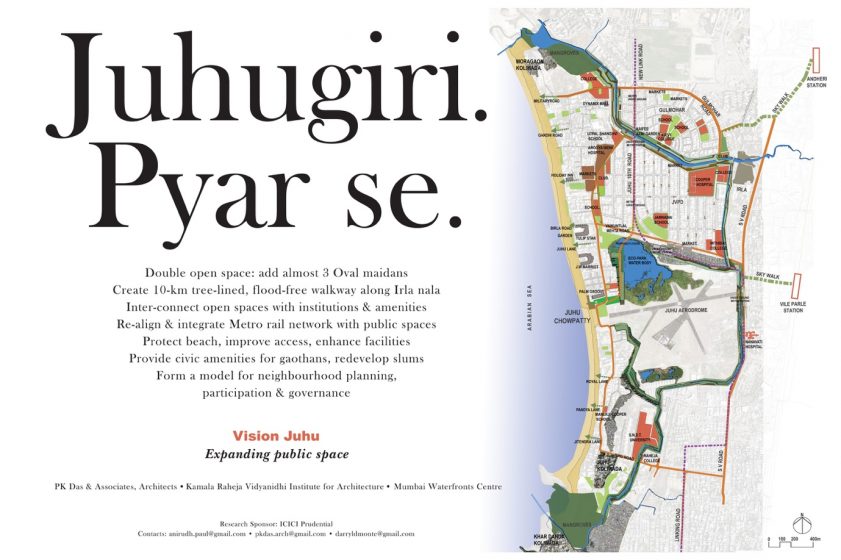

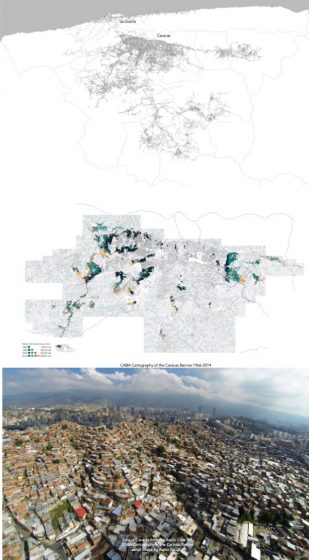

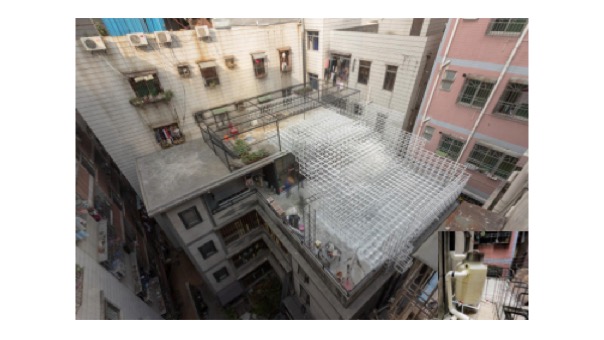

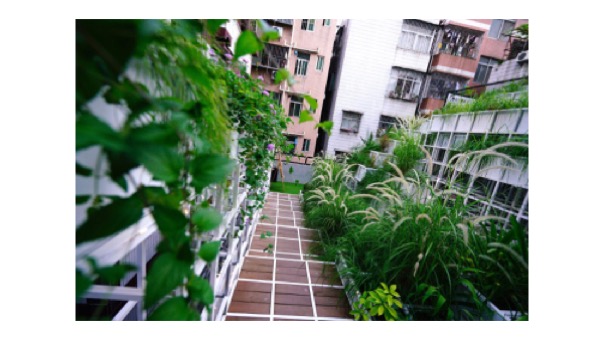

Given the inevitability of urban growth, we must act to minimize and offset associated biodiversity losses, seeking biodiversity net gain wherever possible, particularly if biodiversity hotspots are disproportionately threatened by the process (McDonald, et al., 2018). The integration of biodiverse green space into the urban realm also brings multiple ecosystem services (Grant, 2012), including positive (biophilic) effects on our psychological well-being, delivering a dose of ‘Vitamin N’ or ‘Nature’s Fix’, to borrow the biophilic terminology of Richard Louv (2017) and Florence Williams (2017) respectively. This entails squaring the circle when it comes to maximizing the environmental benefits of compact-city living, while at the same time providing adequate urban greenspace (Garland, 2016). In this respect, the application of Jane Jacobs’ (1961) “density done well” philosophy will be critical. Urban green spaces must be designed to be multifunctional, working hard to integrate biodiversity and other services where space is at a premium (Photos 1-3). Density done well, of course, also means getting more out of built infrastructure, i.e., improving sanitation, housing, public transport, etc., and avoiding sprawling slums and shanty towns in developing countries.

The real culprit behind biodiversity loss

Over the last 50 years, the conversion of natural ecosystems for crop production and pasture has been far and away the primary cause of biodiversity loss (Benton et al., 2021). Cropping and livestock production occupies approximately 50% of the planet’s habitable land. Once natural habitats have been removed to establish agricultural systems there are often limited opportunities for wildlife to coexist due to heavy reliance on agrochemicals, and because of monocultural and deep tilling practices. Our food system is also an important driver of climate change.

While we must develop the capacity to feed at least 10 billion people well before the end of the century, this can be achieved while also significantly increasing the coverage of protected areas for the benefit of wildlife and the provision of ecosystem services. Various credible approaches have been proposed, although the most effective mechanism for reducing pressure on ecosystems would be a transition towards plant-based diets, as substantially less land is required per calorie produced in contrast with diets including a significant meat and dairy component (Poore & Nemecek, 2018; Benton et al., 2021; Ritchie, 2021; Monbiot, 2022). The IPCC (2019) also asserts that a significant shift to plant-based diets would provide a major opportunity for mitigating and adapting to climate change. Additional benefits would include improved dietary health and a decrease in the likelihood of pandemics. However, despite clear evidence governments remain reluctant to advocate such a transition (Islam, 2021).

Shifting baseline syndrome

Putting aside global issues and returning to first-world problems and the fears of the UK’s general public, I often struggle to fathom why disproportionate blame is put on urbanization rather than farming in explaining the impoverishment of the nation’s biodiversity. Note that the UK is one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world due to agricultural land use patterns (Davis, 2020). Many people seem assured that all is well simply from the superficial greenness of the UK’s countryside, even though very little significant wildlife can be found across large parts (Packham & McCubbin, 2020; Monbiot, 2022). They see what is there (greenery) rather than what is missing. Each generation, therefore, redefines what it thinks of as natural and so there is an ongoing reduction of standards and acceptance of degraded natural ecosystems caused by unsustainable agricultural practices; the phenomenon known as shifting baseline syndrome. According to Tree (2018), the British have “pre-baseline amnesia, we forget that there was once more, much much more”.

The myth of the UK’s green and pleasant land has been perpetuated by the absolute conviction of large landowners and the National Farmers Union who have had more influence with the Government and have been more adept at spinning themselves as custodians of the countryside than conservation bodies (Macdonald, 2018; Packham & McCubbin, 2020).

As a consequence of intensive agricultural practices, some studies are now finding enhanced biodiversity in towns and cities contrasted with the neighboring countryside, ranging from increased bee species-richness in the UK (Baldock et al., 2015) to Leopards in Mumbai (Braczkowski et al., 2018).

Conclusions

Ongoing urban growth certainly poses many challenges to the environment and every effort should be made to minimize and offset losses, and wherever possible integrate biodiversity into the urban realm, not only to benefit nature itself, but also to provide ecosystem services, including biophilic benefits. However, the impact of urbanization needs to be kept in perspective compared with the much greater threat to biodiversity coming from our unsustainable global food system.

It should also be recognized that urban coverage is only 1% of the land area while accounting for 55% of the global population. Therefore, an urbanized world, particularly one that seeks opportunities for densification and minimizes sprawl, frees space for other uses including protected areas for wildlife. However, whether we allow more space for nature outside of our cities will mostly depend on whether we choose to adopt more sustainable approaches to food production.

Lincoln Garland

Bath

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Dr. Mike Wells and Gary Grant for their kind feedback on the article.

References

Baldock, K.C.R., Goddard, M.A., Hicks, D.M., Kunin, W.E., Mitschunas, N., Osgathorpe, L.M., Potts, S.G., Robertson, K.M., Scott, A.V., Stone, G.N., Vaughan, I.P. & Memmott, J. (2015). ‘Where is the UK’s pollinator biodiversity? The importance of urban areas for flower-visiting insects’, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 282, 20142849

Benton, T.G., Bieg, C., Harwatt, H., Pudasaini, R. & Wellesley, L. (2021). Food System Impacts on Biodiversity Loss: Three Levers for Food System Transformation in Support of Nature. Chatham House, the Royal Institute of International, London.

Braczkowski, A.R., O’Bryan, C.J., Stringer, M.J., Watson, J.E.M., Possingham, H.P., & Beyer, H.L. (2018). Leopards provide public health benefits in Mumbai, India. Frontiers in Ecology and Environment, 16, 176–182.

Carson, R. (1962). Silent Spring. Penguin Classics, Chicago.

Catalano, C., Meslec, M., Boileau, J. et al. (2021). Smart sustainable cities of the New Millennium: towards design for nature. Circular Economy and Sustainability, 1, 1053–1086.

Connolly, M., Shan, Y, Bruckner, B., Li, R. & Hubacek, K. (2022). Urban and rural carbon footprints in developing countries. Environmental Research Letters, 17, 084005.

Davis, J. (2020). UK has ‘led the world’ in Destroying the Natural Environment. Natural History Museum: News. Retrieved from https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2020/september/uk-has-led-the-world-in-destroying-the-natural-environment.html

Delden, S.H., Sharath-Kumar, M., Butturini, M., Graamans, L.J.A., Heuvelink , E., Kacira, M., Kaiser, E., Klamer, R.S., Klerkx , L., Kootstra, G., Loeber, A., Schouten , R.E., Stanghellini, C., Leperen, W., Verdonk, J.C., Vialet-Chabrand, S., Woltering, E.J., Zedde , R., Zhang, Y. & Marcelis, L.F.M. (2021). Current status and future challenges in implementing and upscaling vertical farming systems. Nature Food, 2, 944–956.

EU Joint Research Center (2019). The Urban Planet: Productive Land is Lost to Urbanization. Retrieved from: https://wad.jrc.ec.europa.eu/urbanplanet

Garland, L. (2016). The Case for High-Density Compact Cities. Bulletin of the Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management: In Practice, 92, 32-35.

Glaeser, E. (2012). Triumph of the City: How Urban Spaces make us Human. Pan Books, London.

Grant, G. (2012). Ecosystem Services Come To Town: Greening Cities by Working with Nature. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford.

IPCC (2019): Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. IPCC.

IPCC (2022). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Islam, F. (2021). Climate plan urging plant-based diet shift deleted. BBC News, 20 October. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-58981505

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Random House, New York.

Kingsnorth, P. (2005). Your Countryside, Your Choice. CPRE, London.

Lerch, M. (2019). Regional variations in the rural-urban fertility gradient in the global South. PLOS ONE, 14, e0219624.

Li, K. & Lin, B. (2015). Impacts of urbanization and industrialization on energy consumption/CO2 emissions: Does the level of development matter? Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 52: 1107-1122.

Louv, R. (2017). Vitamin N: The Essential Guide to a Nature-Rich Life. Algonquin Books, Chapel Hill.

Macdonald, B. (2018). Rebirding: Rewilding Britain and its Birds. Pelagic Publishing, Exeter.

McDonald, R. (2016). Why stopping urbanization is not only impossible, but misses the environmental point. Cool Green Science: Smarter By Nature. Retrieved from: https://blog.nature.org/science/2016/03/10/why-stopping-urbanization-impossible-misses-environmental-point-cities-conservation/#:~:text=First%2C%20it%20is%20not%20clear,stop%20urbanization%20have%20largely%20failed.

McDonald, R.I., M.L. Colbert, & Hamann, M. (2018). Nature in the Urban Century: A global assessment of where and how to conserve nature for biodiversity and human wellbeing. The Nature Conservancy, Arlington.

McKinney, M. (2015). Urbanization, biodiversity, and conservation: the impacts of urbanization on native species are poorly studied, but educating a highly urbanized human population about these impacts can greatly improve species conservation in all ecosystems. BioScience, 52, 883–890.

Mitchel, J. (1970). Big Yellow Taxi. Reprise Records.

Moghimi, F. (2021).Vertical Farming Economics in 10 Minutes. Rutgers Business Review, 6, 122-131.

Monbiot, G. (2022). Regenesis: Feeding the World without Devouring the Planet. Penguin, London.

Office for National Statistics (2019). UK natural capital: ecosystem accounts for urban areas. Retrieved from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/environmentalaccounts/bulletins/uknaturalcapital/ecosystemaccountsforurbanareas

Owen, D. (2011). Green Metropolis: Why Living Smaller, Living Closer, and Driving Less Are the Keys to Sustainability. Riverhead, New York.

Packham, C. & McCubbin, M. (2020). Back to Nature: How to Love Life and Save it. John Murray, London.

Pearce, F. (2010). Peoplequake: Mass Migration, Aging Nations and the Coming Population Crash. Transworld Publishers, London.

Poore, J. & Nemecek, T. (2018). Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science, 360, 987-992.

Ritchie, H. (2021). If the world adopted a plant-based diet we would reduce global agricultural land use from 4 to 1 billion hectares. Our World in Data. Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/land-use-diets

Ritchie, H. & Roser, M. (2019). Land Use Published online at Our World In Data. Retrieved from: ‘https://ourworldindata.org/land-use’

Tacoli, C. (2015). Stopping rural people going to cities only makes poverty less visible, and stripping migrants of rights makes it worse. IIED blog. Retrieved from: https://www.iied.org/stopping-rural-people-going-cities-only-makes-poverty-less-visible-stripping-migrants-rights-makes

Tree, I. (2018). Wilding: The Return of Nature to a British Farm. Pan Macmillan, London.

UNDESA (2009). Urban and Rural Areas 2009. United Nations, New York.

UNDESA (2019). World Urbanization Prospects. United Nations, New York.

UNDESA (2022). World Population Prospects 2022 Press release: World population to reach 8 billion on 15 November 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/wpp2022_press_release.pdf

Williams, F. (2017). The Nature Fix: Why Nature Makes Us Happier, Healthier, and More Creative. W.W. Norton & Company, New York.

Wood, A., Bhardwaj, A., Seltzer, C. & Warren, S. (2021). Green Space in Singapore. Retrieved from: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/aad59652543445cbb941b13b0b9c35d7

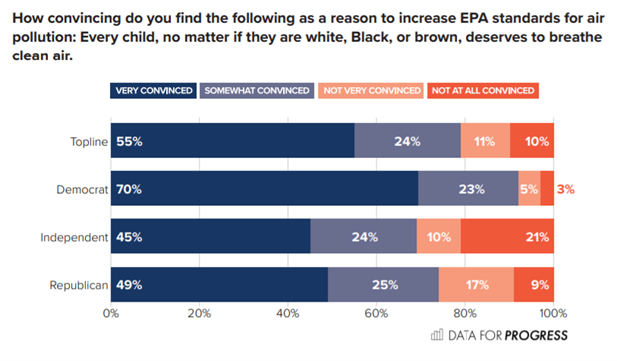

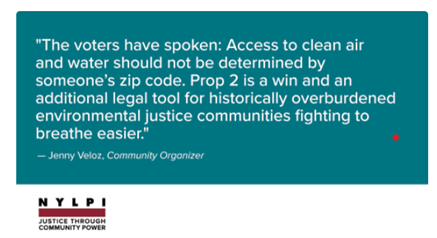

Section 19 is a clear recognition that environmental rights belong to everyone—that no people and no neighborhoods can be sacrificed on the altar of economic growth.

Section 19 is a clear recognition that environmental rights belong to everyone—that no people and no neighborhoods can be sacrificed on the altar of economic growth.

The state has an unambiguous mandate to protect New Yorkers’ right to breathe clean air, drink clean water, and live and work in a healthy environment. Everyone exercising governmental authority, including agencies and local government, has an obligation to protect environmental rights, to promote actions designed to preserve and enhance these rights, and to take affirmative steps to provide a healthy environment to all New Yorkers, including intervening when these rights are jeopardized. Protecting clean air and water must shape how all state law is interpreted and applied. State actors will have new grounds to justify more rigorous enforcement or to defend state environmental legislation from attack by polluting industry.

The state has an unambiguous mandate to protect New Yorkers’ right to breathe clean air, drink clean water, and live and work in a healthy environment. Everyone exercising governmental authority, including agencies and local government, has an obligation to protect environmental rights, to promote actions designed to preserve and enhance these rights, and to take affirmative steps to provide a healthy environment to all New Yorkers, including intervening when these rights are jeopardized. Protecting clean air and water must shape how all state law is interpreted and applied. State actors will have new grounds to justify more rigorous enforcement or to defend state environmental legislation from attack by polluting industry. The Judiciary must assess whether government action has violated these rights

The Judiciary must assess whether government action has violated these rights

References

References

On the lighter side, Emily Hiestand’s “Zip-A-Dee-Do-Dah” is another stand out, full of wry observations about the goings-on of nesting blue jays—“the bird of the postmodern, of invention and recycling, of found art.” Among these and the many other excellent essays in the collection, Stephen Harrigan’s “The Soul of Treaty Oak” is masterful, a story that is equal parts murder mystery, mystical circus sideshow, and compassionate commentary about the human search for connection—in this case, with the venerable but beleaguered Treaty Oak in Austin, Texas, a being “older than almost any other living thing in Texas, and far older than the idea of Texas itself” that becomes a magnet for clashing values after the tree is intentionally poisoned.

On the lighter side, Emily Hiestand’s “Zip-A-Dee-Do-Dah” is another stand out, full of wry observations about the goings-on of nesting blue jays—“the bird of the postmodern, of invention and recycling, of found art.” Among these and the many other excellent essays in the collection, Stephen Harrigan’s “The Soul of Treaty Oak” is masterful, a story that is equal parts murder mystery, mystical circus sideshow, and compassionate commentary about the human search for connection—in this case, with the venerable but beleaguered Treaty Oak in Austin, Texas, a being “older than almost any other living thing in Texas, and far older than the idea of Texas itself” that becomes a magnet for clashing values after the tree is intentionally poisoned.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation