about the writer

Diego Borrero

Diego Borrero Magana works to promote social inclusion and create better cities. He has advised governments on regulatory reform and competitiveness in Latin America, Africa and Europe. He is currently an advisor for the Just Cities initiative of the Ford Foundation. @diegoborrerom

Diego Borrero

Natalia, a cardiologist living in the west of Cali, and Beatriz, a store manager from the east of Cali, share two passions: salsa dancing and biking. When they first heard about the Cali Green Corridor they reacted like most caleños: excited about a project that will change their lives but skeptical about its feasibility. Indeed, the corridor is an ambitious project to be built on 17km of old railway running from north to south (plus a 5km east-center section). This new backbone of the city will add close to 2 million square meters of public space and a clean transport solution for Cali’s mobility challenges. With the Green Corridor, Cali is placing its greatest bet towards sustainable development.

Green can renew life

The “green” of the corridor is not only about the grass and the trees. It is also about the city dwellers seeking an oasis: a safer, cleaner, and happier space for their everyday lives.

But people don’t come spontaneously to a space that has been abandoned and unsafe for decades. Through its design, the corridor must inspire life to thrive in it, with culture, sports and businesses flourishing inside and around it, as engines for its sustainability.

The corridor needs to prove to citizens—with facts—that it can be a landmark for concerts, exhibitions, sports, and other outdoor celebrations in a city blessed by summer weather and coastal breeze all year long.

Green can be inclusive

In previous administrations, the space for the Green Corridor was planned to become a toll highway which would increase pollution and social divide; placing higher income households in the west and lower income households to the east. The Green Corridor will do the opposite.

Cali has often prioritized motor vehicles and enclosed recreational facilities, a trend that has eroded social integration. The corridor will now connect the east and west of the city, and its people. The increase of public space—from 2.5m²/habitant to 3.7m²/habitant—with bike lanes, pedestrian paths and cultural facilities will play more than a recreational a role: it will act as a catalyst for human interaction, bringing together people and interest groups and enabling ideas to circulate in a boundless and healthy environment.

However, such social integration can only happen if the corridor is promoted from its very beginning as welcoming all citizens. Business and real estate development in the corridor and alongside it must be for mixed income and usage. It cannot be conceived—and then perceived—as a park “for the rich” or “for the poor”. The Green Corridor must be a space to celebrate Cali’s diversity.

Green can lead to greener

The corridor can become a proxy of a better city within the city. Its ripple effect can demonstrate how public spaces may be put to better use and break negative perceptions about pedestrian streets, bike lanes and public transportation. It will showcase an optimal situation where everyone—citizens, businesses and government—benefit and learn from turning “inactive” places into opportunities.

In addition the project is being developed with strong participation from citizens. A successful experience bringing together government and civil society will have the potential to strengthen both and replicate this symbiotic model.

Green is the future

Cali is experiencing a new wave of optimism, repatriated talent, visionary leadership and civil society engagement. The Green Corridor will demonstrate that Cali has the capacity to put citizens at the top of its priorities. When this new landscape comes to fruition, Natalia and Beatriz will not only share their passion for salsa and biking, but the pride of living in a more inclusive and greener city.

More than ever, green is the color of hope.

about the writer

Kelly Brenner

Kelly Brenner is a naturalist, photographer and the author of The Metropolitan Field Guide

Kelly Brenner

With so many people now living in cities, and with an increasing detachment from nature, any urban nature we design and create should first and foremost be aimed at reconnecting the human population to nature. There are too many ecologically illiterate or ill-informed people living in cities.

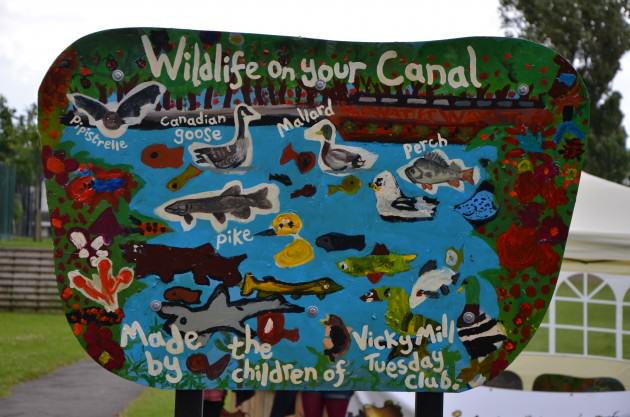

Recently I read some comments that illustrated this point. It was a case of developers versus bird habitat; some believed it was very simple case of humans versus animals and humans should always be placed first. Many people see nature as a luxury, something we do in our free time, and fail to recognize that we are dependent on the natural world for survival. Birds aren’t just nice to watch, they perform pollination, pest control, seed dispersal and waste management. Insects are even more essential as our world would collapse without them. This is why we need green spaces in the city—to help increase awareness of the importance of nature.

In Seattle we have an excellent example called the Pollinator Pathway. This is a single street (although currently expanding to a second), aimed at creating a corridor for pollinators, connecting Seattle University to Nora’s Wood, a small city park. It has received a great deal of attention. The creator Sarah Bergmann—who won a Genius Award in Art from the Stranger—had an exhibit at Seattle Art Museum’s Olympic Sculpture Park and won the prestigious Betty Bowen Award for art, all in recognition of the Pollinator Pathway. It’s been featured on NPR, the Seattle Times, Grist, KEXP and several other news outlets.

This project has touched a great many people locally as well, starting with the homeowners whom agree to turn their grass strip between the sidewalk and road into habitat. Seattle University, University of Washington and Cornish College of the Arts have all incorporated the Pollinator Pathway into courses. Many work parties of volunteers have helped install the gardens and there have been several successful fundraisers to help purchase materials. To analyze and provide help with future designs and improvements, an entomologist from the Woodland Park Zoo has been monitoring the gardens since 2010.

Now for a relatively small green corridor in one city, that’s quite a lot of outreach. From my initial statement I believe in this respect it has been a huge success. Many people are now not only aware of this project, but they also know that pollinators need our help, that we rely on them and that we can provide travel corridors for them in the city. It also demonstrates that many people can indeed work together to create corridors in the city. It also shows that enthusiasm is there and can be fairly contagious.

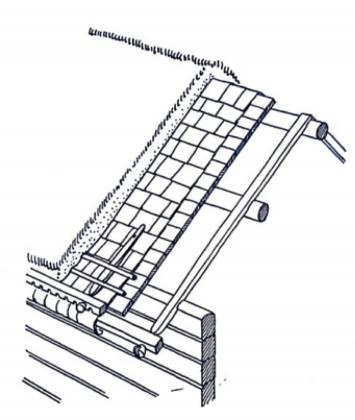

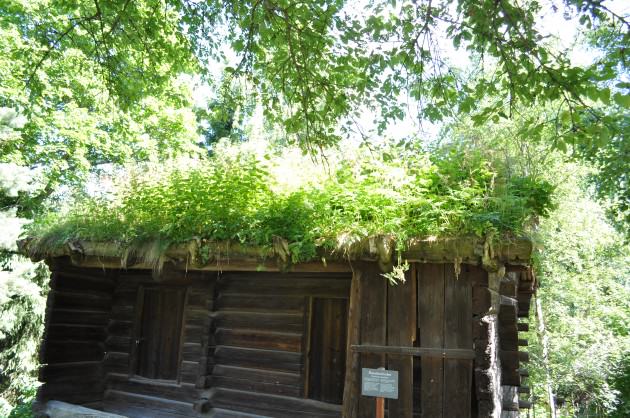

Although the idea of nature in cities is not a new one, it’s far from standard or common among city planners, architects and landscape architects. We have a lot of work to do in this new Anthropocene era. Cities have much potential for adding and improving our green spaces. We have a great deal of existing infrastructure that would work wonderfully with the creation of green corridors such as waterways, power lines, transit corridors; both public transit and streets, and rooftops. We have to start thinking creatively about how to integrate green space and habitat with what is already there. If we had nature built into our infrastructure, we’d encounter it regularly, every day while going about our lives. The more we can bring nature, even if it’s simply the idea of it, to the city, the more we can connect to it and start to care about it as something that’s not simply a luxury item.

about the writer

Lena Chan

Lena Chan is the Director of the National Biodiversity Centre (NBC), National Parks Board of Singapore.

Lena Chan and Geoffrey Davison

Natural habitats areas, whether spontaneous or human-created, exist in fragmented patches in cities. Some of these sites are connected due to human intervention through the creation of green corridors. To be able to objectively assess the effectiveness of these green corridors, the project must be well-planned, giving due consideration not only to the objectives and implementation details but also ensuring that monitoring and evaluation criteria are included in the experimental design. Some thought should be given to the prevention of invasive alien species during the process of creating green corridors.

Green corridors can also evolve spontaneously.

For example, roads can form the infrastructural backbone of green corridors if they are innovatively enriched with plants that serve ecological functions. Some of these ecosystem services include enlarging the effective habitats for birds, small mammals, butterflies, bats, dragonflies, etc. through forming linkages between core biodiversity areas. Increasing the tree canopy cover of roads can also contribute to the reduction of ambient temperatures, reduction of noise, decrease of pollution, and improvement of the aesthetics of the environment.

When planting along roads is synergised with that of the surrounding landscapes, like parks, residential areas, schools, hospitals, etc., the thin linear corridors broaden to form more effective spaces for wildlife in urban settings.

Green corridors as biological systems will inevitably change in structure and form over time. Hence, to be realistic, the ecological functions of these green corridors will also change as the habitats mature.

about the writer

Geoffrey Davison

Dr. Geoffrey Davison is Deputy Director (Terrestrial) at the National Biodiversity Centre, National Parks Board of Singapore. His latest book is “Wild Singapore”.

about the writer

Susannah Drake

Susannah C. Drake FAIA FASLA is a Principal at Sasaki and founder of DLANDstudio. Susannah lectures globally about resilient urban design and has taught at Harvard, IIT, and the Cooper Union among others. Her award-winning work is consistently at the forefront of urban climate adaptation innovation. Most recently “From Redlining to Blue Zoning: Equity and Environmental Risk, Liberty City, Miami 2100,” was included in the 2023 Venice Biennale. Her first book “Gowanus Sponge Park,” was published by Park Books in 2024. Her work is in the permanent collection of MoMA.

Susannah Drake

Linear Parks

Over the last year my firm DLANDstudio worked for the Trust for Public Land on a feasibility study for a linear park project in New York City called The QueensWay. The QueensWay site is a 3.5-mile, long-abandoned rail corridor that runs from Forest Hills to Ozone Park. The path starts on an embankment and then cuts through the terminal moraine of the Wisconsin glacier in a ravine-like area before transitioning to a structured rail trestle. The new trail will form important connections to Forest Park, a large pastoral park at the heart of the path.

Linear parks are all about connection; In this case forming important safe routes for kids to local schools, off-road paths for cyclists to subways for shortened commute times, connection to neighborhood commercial corridors, and access to new planned cultural programming. A recent United States National Institute of Health study suggests that people living within a half mile of a park are much more likely to engage in vigorous physical activity. The public health potential is tremendous. When completed, the 350,000 people who live within a ten minute walk of the park will comprise the most diverse local demographic catchment areas of any park in the city.

Richard T.T. Forman’s theories of Landscape Ecology suggest that long, linear, continuous landscapes are more environmentally productive, fostering a broader habitat for a diverse range of plants, animals, birds, and butterflies, than disparate patches of park land. The site with its continuous corridor of naturally occurring trees will be augmented with new plantings to create enhanced habitat. Its location along the North American flyway is also an important stopover breeding ground for the Monarch Butterfly on their migration route to Mexico.

Transportation infrastructure has transformed the global landscape. In the case of the Queensway, Highline, Chicago’s 606 Trail, and many others around the world, abandoned rail infrastructure has been replaced by park land. This is a laudable and important effort. However, an opportunity exists to transform working linear transport systems that often bisect and divide neighborhoods into more responsible actors in urban design. Dlandstudio is working on a range of projects that ameliorate the impacts of raised viaducts, highway trenches, and train trestles that adversely impact urban life. As the Under the Elevated Urban Design Fellow for the Design Trust for Public Space, the firm is developing designs that address, acoustic, air quality, public safety, way finding, and storm water management issues. Through a series of prototypical projects that include new program, lighting, sound buffers, green infrastructure and ecological strategies, new systems will be tested as pop-up applications to gage public interest and build support. The designs will then be developed further as pilots for system-wide transformation and, when proven, implemented on a broad scale.

On a more local scale the Brooklyn Queens Expressway is the muse of the firm. From taking water from the raised highway into pilot modular storm water swales we call HOLDS (Highway Outfall Landscape Detentions System) to strategies for capping the trench in the brownstone neighborhoods of Brooklyn, we see tremendous potential in transformation of the linear corridor to make it more environmentally and economically productive. In particular we are focused on creating a new cap over the BQE in South Side Williamsburg.

For the past seven years we worked with the local community to develop a plan to add recreation space over the highway trench. The plan would not only enhance the ecology with new trees and better storm water management, it would unify and strengthen the identity of the local neighborhood. The mostly Latino area is currently plagued by poverty, obesity, gang violence, high childhood asthma rates and traffic fatalities. BQGreen—the name we developed for the park—will eliminate territorial boundaries, clean the air of excess particulate matter, create safe walks for kids to school, provide new active recreation space for all ages and add a new community center with pool.

All of this will be accomplished by leveraging overdue infrastructure replacements. New bridges that cross the highway will expand and connect to create new decked park space. This area wil be ringed by trees and plantings, creating a new ecological corridor. While this is a specific proposal for a particular place, it can be replicated and expanded to have an impact on broader and longer corridors in cities across the country and around the world.

about the writer

Irene Guida

Irene Guida, PhD in Urbanism, is a researcher at IUAV Università di Venezia. Among her publications, L'Acciaio tra gli ulivi, Linkiesta, Milan (January 2012), is an experiment in sharing research to a common public, with high quality content.

Irene Guida

What is an ecological corridor?

As an ecological device, the corridor has been conceptualized according to the island theory in biogeography, expounded by Robert McArthur and Edward Wilson in 1967. These young zoologists, among other things, studied birth rates and population dynamics as they relate to processes of territorialization. Their innovative work consisted of ascertaining a general theory from data, in relating the frequency of rare species to the extension and age of patches they colonized and used to move along their migration. Their findings, in generalizing the data, was that the frequency of rare species was directly proportional to the dimension of islands, and at the same time inversely proportional to the distance between them. This theory was a continuation of Darwinian studies on evolution and the extinction of species. McArthur and Wilson were interested in understanding which factors mitigated extinction in favour of evolution and the adaptation of species. The influence of the theory of biogeography islands became key to landscape ecologists who interpreted the islands as patches of natural habitats in urban conditions.

Among them a contribution that had received a great deal of attention among planners, was given by Richard T. T. Formann. His primary relevance in this dissertation stems from the clear definition he provided, by means of graphic analysis and representational tools. Additionally, pertinent to this study are his description of plant ecotones in human disturbed environments, through his investigation of the mitigation of large-scale infrastructure, such as roads, and large scale human settlements. Formann’s attention toward corridors is mainly driven by its importance in human settlements, and he carefully defines corridors by shape (curvilinear or linear), dimension (coarse or fine), and connectivity (number of connections leading to a node). Conservation experts agree that streams, riparian corridors and agricultural barriers can provide shelter to wildlife, thus increasing biodiversity, as well as being useful for human settlements, providing biomass, wood, etc. Corridors are hence also key in landscape management and design, and this is why they receive such a great deal of attention among planners.

Ecological corridors’ capacity for providing effective connectivity has therefore been greatly discussed by scholars and ecologists.

Skeptics argue that biotic connectivity through corridors cannot be entirely proven. Beier and Noss, on the other side, argue that correctly designing a study to prove corridor connectivity is difficult because of the high number of variables that must be taken into account (as with the selection of a habitat’s fragmentation species, for instance). So they instead provide evidence of what happens if corridors are eliminated. They affirm that cutting corridors, which link habitat patches, does in effect reduce biodiversity.

In response, other scholars argue that experimental studies can instead be effectively designed, and they go on to attempt proving that ecological corridors have a key role in biodiversity protection when the matrix is particularly poor for species using the corridor.

In conceiving (or conceptualizing) the city as an energy’s flow, the territory of flows does not appear as flat. Drawing sections is thus important for a proper description of this phenomenon. This is why, in studying Gwynns Falls, Victoria Marshall, Brian McGrath (urban designers) and Stuart Pickett and Mary Cadenasso (plant ecologists), also drew several sections, relating patch disturbance with changeling sloping land. Both high resolution ortho–imagery and fine 3D models of the land are key in relating patch dynamics to physical environments and the bodily perception of space.

Summarizing the findings that we have investigated until now, it becomes apparent that the conceptualization of something as a “corridor” is not a neutral gesture, for it carries with it many considerable issues. It seems to me that a biotic turn, which helps territorializing social bodies into natural regions, is involved. This biotic turn is what renders landscape ecology not only a specialized feature, but also something that has great social and political meaning.

What I suggest is that a stronger reflection is needed, which involves a genealogical inquiry over the term corridor, reviewing the analogy in the long term, and a new idea of open public spaces, which cannot be understood if we continue to sever design, aesthetics and history, from biology, economy and natural sciences. Landscape Urbanism urges us to learn about breaking through boundaries and finding new reading and writing methods for our small, globalized, urbanized planet.

about the writer

Marcus Hedblom

Marcus Hedblom is a researcher and analysist at the Swedish University of Agricultural sciences.

Marcus Hedblom

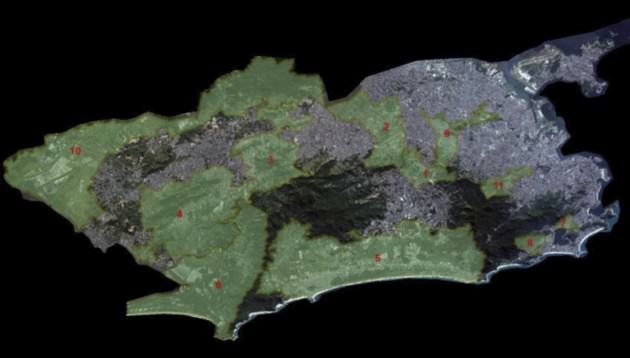

The fear of actual implementation of a green corridor

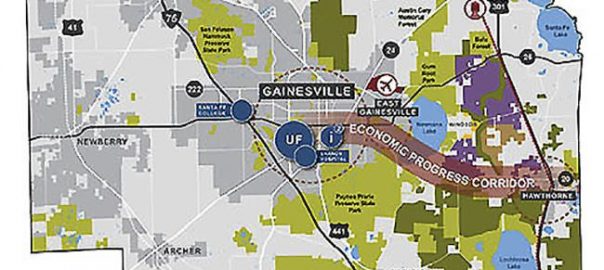

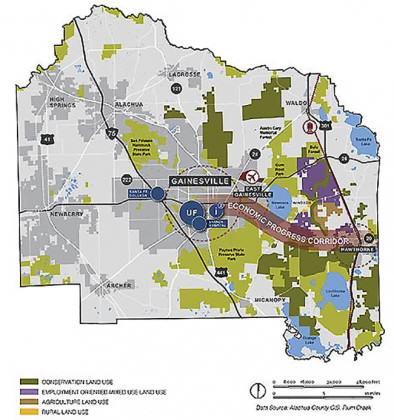

In the making of the Uppsala’s strategic master plan 2010 (Uppsala is the 4th largest city in Sweden), a number of green corridors were suggested by the recreational office. Uppsala has a number of larger green corridors leaping from the center to peri-urban area. Those existing green areas are partly left between houses though the history, some are partly left for recreation others are just left by random. Those green areas were never officially named or put on a map prior to the plan. However, it was a small battle internally in the organization about the drawings and purposes of the corridor. The rhetoric was even highlighted in the city newspaper where the “city architects” mentioned that green areas were “dead hands” on the urban development and the “recreation and conservation” planners emphasized importance of recreation and conservation. In the end both “sides” ended with a map that showed the borders of parks and green corridors with very diffuse (intentionally) borders (see figure below).

Although the borders were diffuse, the revision of the master plan in 2014 made an extra case that further emphasized that the map is only visionary. On the other hand, the writing in the master plan still says that “The city’s green wedges…that link the city’s green structure with the surrounding nature and recreation areas should be protected so that the green linkages persists or develops”. Interesting here is that planning is often very precise when it comes to buildings but to make concrete borders for green areas seems harder.

Although the borders were diffuse, the revision of the master plan in 2014 made an extra case that further emphasized that the map is only visionary. On the other hand, the writing in the master plan still says that “The city’s green wedges…that link the city’s green structure with the surrounding nature and recreation areas should be protected so that the green linkages persists or develops”. Interesting here is that planning is often very precise when it comes to buildings but to make concrete borders for green areas seems harder.

In Stockholm, they have similar corridors and worked a lot with definitions and surveys. I believe that one secret in the success of the work in Stockholm is that they put a minimum width of the corridor: 500 meters. Those 500m makes a distance from disturbing sources as roads and increase social values and also allow habitats in different scales to exist and provide movements for a number of species.

When the society of science has internal discussions about the functions of corridors for humans and species, the planners in cities do not know what to do, or which arguments to use. The city architects in Uppsala fear that 25,000 houses within existing city borders will not fit, or be limited, due to green space. The recreational planners fear that Uppsala will lose attractive recreational and conservational values.

When I worked as a strategic planner in Uppsala, my background as a researcher in ecology put me into difficulties due to the need to generalize. As a scientist, I showed in a study that grassland corridors (resembling road verges) were suitable for movement for butterfly species that were categorized as specialists (not generalists), meaning that they had special preferences for plant species when foraging. However, if a corridor provided very good nectar resources, the specialist butterfly stopped to forage and defend it from other butterflies, making the corridor a potential trap. Thus, telling a planner that they have to make a suboptimal corridor for specialist species is a difficult task.

The distance between the knowledge that a corridor would work, to actual implementation, is difficult.

Back in science again, I believe that it is better to do as they done in Stockholm, to define a minimum width and then work from there with increasing qualities for species and humans. Concretize the borders on a map. As it is now in Uppsala, the diffuse border makes alterations easier and already a road have been built across one part and grasslands for butterflies have decreased.

about the writer

Mark Hostetler

Dr. Mark Hostetler conducts research and outreach on how urban landscapes could be designed and managed to conserve biodiversity. He conducts a national continuing education course on conserving biodiversity in subdivision development, and published a book, The Green Leap: A Primer for Conserving Biodiversity in Subdivision Development.

Mark Hostetler

I am going to focus on the functionality of urban green corridors for wildlife. I do think these corridors could serve as important connectors for significant habitat patches found both within and outside of cities. However, all corridors are not created equal and below, I discuss three important factors when considering the utility of a planned green corridor for wildlife.

1. Which species is the corridor for? This is an important question to answer because corridors for large animals, such as bears, would be much wider than corridors designed for smaller mammals. Also, the mobility of different critters plays a role: butterflies and birds can fly over roads that bisect corridors whereas mammals and reptiles have a relatively difficult time crossing roads. A functional corridor for birds may be viewed more as “stepping stones” compared to a linear corridor with relatively few bisecting barriers for mammals. Often, people think that only large, continuous corridors are noteworthy but I would argue that even small, somewhat disconnected patches of vegetative cover could serve as a functional corridor for smaller species that can traverse built structures. As an example, tree canopy patches that are separated by 45 meters or less (with roads and pavement underneath) can facilitate the movement of forest birds.

2. Management and vegetation structure within a wildlife corridor? Corridors could serve two functions for wildlife—species may be corridor dwellers, where the appropriate habitat structure is available for animals to reside for long periods of time and/or species may be passage users, where animals are in the corridor for a brief period of time and use it primarily to disperse. This has implications for corridor management and vegetation structure. Many urban green corridors are made available for use by citizens and this can raise issues for corridor dwellers and animal passage users. Noise, lights along walking trails, and human activity throughout the interior of the corridor can disrupt corridor dwellers in particular. For example, nesting birds within a corridor where human activity is high would affect reproductive success. It may even affect passage users if the amount of human activity, building structures, and noise is high. In corridors that are heavily used by humans, the presence of passage users (even use as stopover sites by migrating species) is more likely than presence of corridor dwellers.

One way to alleviate the impacts of human activities would be to design paths for humans that go along the very edge of the corridor and occasionally dip into corridor to (for example) see views of a river. This way, there would be areas where corridor dwellers could reside and reduced human activities that may promote passage species as well. Additionally, for both corridor dwellers and passage users, evidence suggests that the amount of native vegetation within a corridor is correlated to use by wildlife. A possible mechanism for this is that native vegetation provides more efficient foraging and functional breeding habitat. Thus, maintain or restoring native vegetation is an important part of retaining corridor functionality. Management actions would include the removal of invasive exotics within the corridor and planting natives.

3. Impacts to corridors from nearby land uses? Pets, noise, lights, motorized vehicles, stormwater runoff, and spread of invasive exotics can negatively impact wildlife use of corridors. These types of impacts typically originate from nearby built areas, especially from densely populated areas. Attention should be focused not only on creating wider corridors (i.e., buffers) in these problematic areas but a management/education plan should be implemented in the built areas. Engaging local citizens about how activities on their property (e.g., planting invasive exotics) and how forays into the corridor (e.g., motorized vehicles) affect wildlife can help mitigate the negative impacts of nearby populated areas.

about the writer

Chris Ives

Chris Ives takes an interdisciplinary approach to studying sustainability and environmental management challenges. He is an Assistant Professor in the School of Geography at the University of Nottingham.

Chris Ives

Urban green corridors are a good example of where we jump ahead to solutions before defining the problem. Before calling for the establishment or protection of corridors, it’s important to consider what kinds of ecological and social objectives we want in our cities. I think that green corridors have great potential because they can perform multiple functions. However, exactly what these desired functions are needs to be clearly defined first before guidelines for their design can be set.

The role of corridors as facilitating movement of organisms across a landscape probably has the least amount of scientific evidence—despite the fact it is the function of corridors that most resonates with people. The purpose of movement is also seldom considered. Ecologically, the movement of organisms is not always desirable, particularly when considering invasive species. Facilitating the movement of plants and animals is most valuable when linking two or more otherwise disconnected populations. The ability of corridors to do this is an area that needs more research effort.

We have much more information on the potential for green corridors to function as habitat refuges in urban areas. Streamside riparian zones are particularly valuable as they are positioned at the interface between aquatic and terrestrial environments and are home to many species. They also help buffer the stream from excess nutrients and pollutants in the landscape. Some research I conducted in northern Sydney, Australia demonstrated that urban riparian corridors sustain complex ant and plant communities [1]. However, their ecological health was generally related more to the landscape context and presence of invasive plants than connectivity or corridor width. This study also demonstrated the importance of considering which taxa are being planned for, since ants and plants responded in different ways to environmental variables.

If large habitat areas do not already exist in an urban landscape, protecting or restoring some may be ecologically more beneficial than implementing a corridor network since narrow corridors are likely to experience significant edge effects and be difficult and expensive to manage. Indeed, even if some large habitat reserves already exist in an urban landscape, biodiversity outcomes may be enhanced more greatly by protecting a habitat type that is presently under-represented in the landscape than by linking up existing habitats that are ecologically similar.

In many cases, it’s likely that the social benefits of corridors will match or outweigh the their ecological benefits in urban landscapes. Corridors have an amazing way of galvanising public interest in conservation and can help connect people with nature. Studies have shown that linear green spaces are vital for facilitating recreational activities [2]. Thus, green corridors are an ideal form of green infrastructure for achieving multiple environmental and social objectives simultaneously. However, there may be some conflicts between designing corridors for human use and appreciation and ecological outcomes. We therefore need to consider exactly what we want corridors to do and weigh carefully the tradeoffs between ecological function, management costs and human uses.

1—Ives, C. D., G. C. Hose, D. A. Nipperess, and M. P. Taylor. 2011. Environmental and landscape factors influencing ant and plant diversity in suburban riparian corridors. Landscape and Urban Planning 103: 372–382.

2—Brown, G., M. F. Schebella, and D. Weber. 2014. Using participatory GIS to measure physical activity and urban park benefits. Landscape and Urban Planning 121: 34–44.

about the writer

Tori Kjer

Tori Kjer, PLA, is the Program Director for the Trust for Public Land's Los Angeles Program.

Tori Kjer

Green Corridors in Los Angeles

Los Angeles is surrounded and interlaced by green corridors that provide a full range of ecological and social functions. These include three mountain ranges encircling the city, a 52-mile river corridor, undeveloped hills, alleys, utility corridors, and parks. Clearly, these green spaces vary tremendously in attributes and uses. But all offer undeveloped space in an otherwise densely populated megalopolis.

Depending on location, green corridors may provide habitat for wildlife and spaces where people can play. Where they connect communities, green corridors may host trails for walking and biking. The San Gabriel and Santa Monica Mountains foothill corridors provide an important green buffer for the city while cleaning the air and providing human habitat and recreation for Angelinos.

Less obviously, the dense neighborhoods in South Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley are laced with 900 miles of alleyways that could serve as multipurpose greenways that would also filter stormwater and provide safe connections between communities. These largely overlooked linear common areas compose nearly 2,400 acres of potential open space.

Similarly, the corridors of the Los Angeles and San Gabriel rivers, when fully greened, could support regional transportation connections for commuters, tourists, and families. Even now, partially developed for transportation, they provide habitat and empty spaces to escape to.

Urban Mountains

The San Gabriel Mountains and foothills constitute approximately 70 percent of open space in Los Angeles County and work hard for Angelinos, providing approximately 35 percent of the region’s drinking water and recreation for the more than 15 million people that live within 90-minutes of the Angeles National Forest. Indeed, the national forest is Los Angeles’ largest playground for hikers, mountain bikers, backpackers, picnickers, and campers, as well as skiers and snowboarders in the winter months.

The mountains’ ecological importance will only increase in coming decades, when they will help ensure that the region remains habitable in the face of climate change. A recent report by the Los Angeles Regional Collaborative for Climate Action and Sustainability predicts that by mid-century, extreme hot days will triple or quadruple for the vast majority of Southern California residents.

Alleys as Green Corridors

Today, The Trust for Public Land’s Avalon Green Alley Demonstration Project is modeling the greening of Los Angeles alleyways. This project will create the first green alley network in South Los Angeles. It is also the first alley retrofit anywhere in Los Angeles to incorporate greening and the first to demonstrate the potential of green alleys to transform neighborhoods of significant density and poverty.

Retrofitted to green corridors, alleys will help link residents to homes, nearby schools, parks, and businesses. Decorated with community art and planted with native and edible landscaping, alleys will become welcoming community spaces for gathering and recreation. Outfitted with permeable paving, dry wells, and other stormwater-control infrastructure, green alleys also will increase the reliability of local water supplies by reducing runoff, improving water quality, and supplementing the City’s water supply via groundwater recharge. Nuisance flows and small rain events will be captured and percolate underground to be temporarily stored prior to infiltrating into the soil.

Like our the green corridors provided by our mountains, our alleys transformed into green corridors could play an important role in keeping the Los Angeles region livable in the future.

about the writer

Kathryn Lwin

Kathryn Lwin is the Founder Director of the River of Flowers, a nonprofit, eco-social enterprise working with community groups and other organisations to create trails or ‘rivers’ of wildflowers and wild flowering trees as forage and habitat for bees and other pollinators in cities.

Kathryn Lwin

‘Human’ and ‘Nature’ are words that go together well. Humans cannot survive without nature; humans have provided nature with the urban environment, one in which it abounds! It’s not cities, which are incompatible with nature but our systems of urbanization and modern agriculture. Such practices have resulted in reduced territory and fragmentation, isolating wild species populations and leaving them vulnerable to loss and extinction. Wild flora and fauna are seen as competitors for space in which to grow food, construct buildings or lay down lines of transport.

If humans were to abandon a city, a green torrent of vegetation would soon rush in to fill in the gaps, facilitating the movement of flora and fauna from one ecosystem to another. Plants would clamber across the built surfaces of the city, swoop over roofs and walls, flow along the linear roadways, railways and waterways, connect up the networks of open spaces designated as city parks, gardens, playgrounds, car parks, cemeteries, urban farms and the non-designated, abandoned areas of vacant lots and brownfield sites with the nature reserves, often girdling the city outskirts. So if humans planted strategically, aiding and abetting this natural flow, we should expect such man-made ‘green corridors’ to work just as well.

Research shows the multiple benefits that plants bring to the urban landscape from cooling and cleaning the air to softening impervious surfaces, lessening flood risk and improving the quality of life by raising health levels. Green spaces have even been shown to reduce crime rates and slow city traffic. City governments could gain even more ‘added value’ from plants by fostering sustainable urban food growing and in the process shrink the miles from ‘farm to fork’ with all attendant implications for carbon emissions, air quality, energy consumption and water use. But to feed itself, a city must first feed its pollinators.

We are already increasing the number of multi-functional green spaces such as rain gardens and pocket parks in a city, but to make these places where pollinators can feed and reside, we need to increase the percentage of diverse, native, insect-friendly forage plants (including wind-pollinated trees for early pollen) as well as nesting and hibernation sites and access to clean water. With more attention to species selection and responsiveness of procurement, a city would add great ‘pollination’ value.

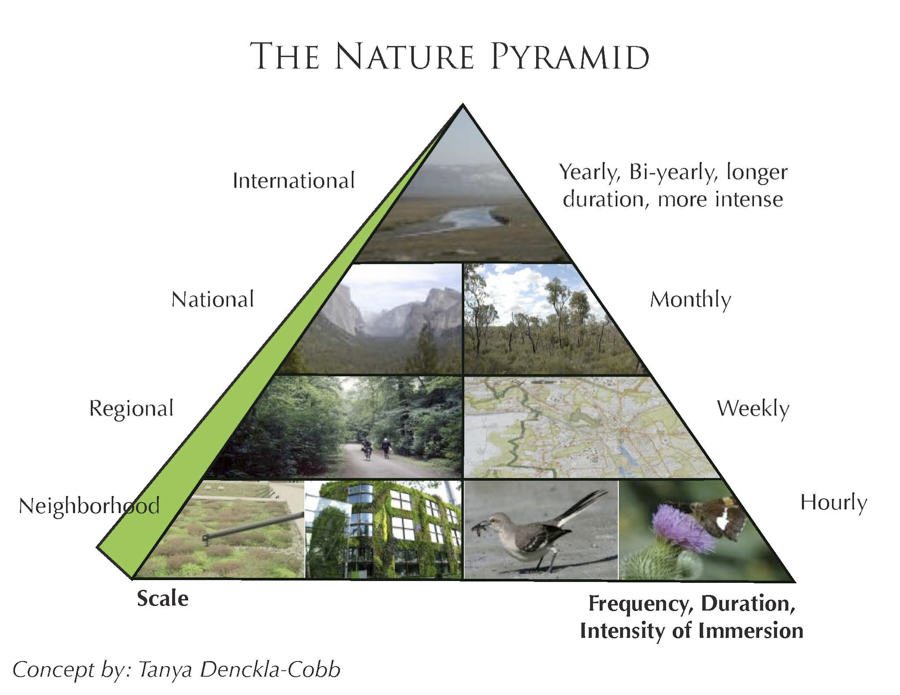

By auditing and mapping the city for availability and distribution of potential and actual growing sites, as the Urban Design Lab has done in New York, we can begin to design ‘pollination’ rather than ‘green’ corridors to criss-cross a city. These would facilitate the ‘flow’ of wild pollinators and plants between the built environment, urban farms and nature reserves.

In London, the Edible Bus Stop has planted fruits and vegetables with the local community along the bus routes in Lambeth while in formal Regents Park, edible crops and beehives now flourish beside stately ornamentals. At the Kings Cross Skip Garden, young people are growing food and wildflowers in building skips, which are simply lifted up and re-sited when the space is scheduled for re-development. Alongside the railway stations and gardens in Hackney, wildflowers and orchards have gained a stronghold, tended by local community gardeners and beekeepers keen to keep their neighbourhood fit for bees. On the River Thames, an urban forest glade and garden, rooted on barges moored beside Tower Bridge, float just a short bee flying distance away from wildflowers blooming on the Queen Elizabeth Hall roof at the Southbank Centre and edible harvests in the housing estates of Bermondsey.

Community initiatives like this are starting to create organic ‘pollination’ corridors or ‘rivers of flowers’ in cities all over the world as people actively engage with one another to grow food, wildflowers or both for the benefit of humans and nature.

about the writer

Pierre-André Martin

Pierre-André has a Landscape architecture degree from École Nationale Supérieure de Paysage de Versailles in France and a MBA in environment from COPPE, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. He has been a leader over 13 years in urban and environment necessities in France and Brazil, taking care of the integration of urban projects with natural and the urban environment through diagnosis, guidelines and licensing.

Pierre-André Martin

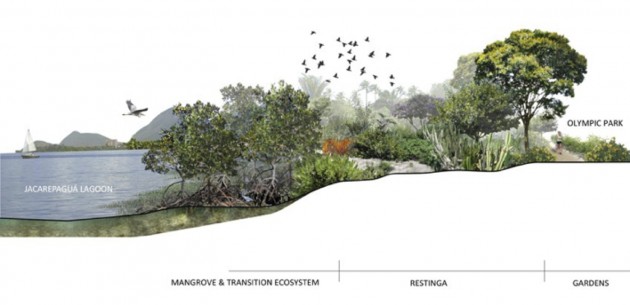

In Rio de Janeiro, where biodiversity rates are among the highest on Earth, green corridors ecological function is heroic, but actually their internal structure is not planned or projected and their ecological characteristics are mainly spontaneous and perceived by most of the population as “remaining” areas or waste land. They work as green, blue and faunal struggling for connections, but they are very vulnerable at the same time, receiving huge amount of waste, sewage, slum construction and invasive species. It is a tense situation.

Environmental laws in Brazil restrict from human occupation within 30 meters, at least, from the edges of water bodies. These legal instruments create an extended network of green corridors along natural, rural and urban areas. Actually architects and urban planners see these areas as “environmental” areas and have typically excluded them from their practice in the city.

In my opinion the strongest characteristic of a corridor is their linearity—in their linearity the potential for more social function, especially in Rio de Janeiro situation. The whole city suffers from mobility problems and is mainly connected by an arid and polluted road system focused on car transportation. Low impact mobility like pedestrian areas or cycling lanes can be inserted in this ecological network of environmental corridors with a specific design, using this mobility challenge as an opportunity for focused structural planning and projects. Outside of these areas the road and transportation systems require serious upgrades in their biological and hydrological aspects, as they are also linear systems and must support a wider range of ecological functions be transformed into a support for life systems and not only a “A to B” transportation system.

A key impediment to the useful improvement of these potential corridors is the public’s prejudice—the perception by most of the population that they are useless and meaningless areas, turning them into areas excluded from the mental geography of its inhabitants. This is why I believe in the critical need for social uses of these corridors, mixing appropriate solutions of transport and promoting environmental education to change the perception of this natural system within the city.

about the writer

Colin Meurk

Dr Colin Meurk, ONZM, is an Associate at Manaaki Whenua, a NZ government research institute specialising in characterisation, understanding and sustainable use of terrestrial resources. He holds adjunct positions at Canterbury and Lincoln Universities. His interests are applied biogeography, ecological restoration and design, landscape dynamics, urban ecology, conservation biology, and citizen science.

Colin Meurk

Urban green corridors are a subset of corridors in general, and the same ecological laws will apply, regardless of context. What then is different about ‘urban’ that could change the outcomes? Clearly ‘people’ is the overriding factor (social, cultural, psychological, behavioural, tribal, anti-social). The indirect ecological consequences of stress and disturbance intensity will slow growth and succession, whereas localised nutrient inputs, irrigation and competition control (gardening) will have the opposite effect. The question is whether corridors enhance biodiversity or accelerate pest dispersion. People will control these outcomes by directive behaviours reflecting their aesthetic and cultural perspectives (creating physical barriers, weed control, trapping, opening up closed canopies to light and weed ingress, or actively planting corridors between isolated/fragmented patches). Clearly the concept of ‘corridor’ has a positive ring to it and for this reason a populist ecology has taken over and resulted in these landscape design features being employed by local governments, stream fishing communities, NGOs, planners and landscape architects.

There is voluminous literature on whether they work or not. One statistically persuasive example is by Damschen et al. (2006) which showed, in a carefully orchestrated experiment with open patches in a matrix of closed canopy forest, that ‘corridors increased plant species richness at large scales’ and there was no weed increase. However, the benefits claimed might equally be explained by mere increase in total area of the patch (the corridor itself). There was no evidence that propagules actually migrated along the corridor. This has been observed at small scales (beetles)—and mammals do hug hedgerows, going somewhere!

I cannot get past an old mate Dave Dawson (an expat NZer who worked for the London Ecology Unit) who wrote an unsung review of Green Corridors in 1991. Certainly at that time there was no unequivocal evidence for migratory/conduit function of corridors in cultural landscapes—rather he saw their value as (edge) habitat in their own right. Any value as conduits would be icing on the cake. Clearly they do have socio-cultural value as the idea of connectedness and ‘tidy frames’ (Joan Nassauer) is appealing and resonates with normative human aesthetics and desire for control. They provide visual amenity; when viewed from the side, they are extensive, and were promoted in England along rail corridors as pleasant outlook for commuters.

NZ like other island nations is acutely aware of the role and debates around long distance dispersal. What seemed like impossible barriers of surrounding hostile oceans, or a matrix of intensive farming, could over time be transgressed even at low probability. It seems there is almost no biological event that has zero probability! For this reason, providing a mix of actual corridors as well as virtual corridors, in the form of stepping stones, is a perfectly valid aspiration. Most flighted wildlife or wind-blown propagules are quite capable of hopping from patch to patch with <200m gaps.

about the writer

Toni Pujol

Toni is an Environment Officer at the Barcelona City Council and an Environmental Scientist at the Autonomous University of Barcelona.

Toni PuJol

Barcelona is working towards a more connected and structured urban green infrastructure

For several years the Mediterranean city of Barcelona (Catalonia) has been committed to preserving and enhancing the natural heritage present in the city. To achieve this in a systematic manner, Barcelona City Council approved a comprehensive strategy in 2012, the Barcelona Green Infrastructure and Biodiversity Plan 2020.

This plan sets out the goals we aim to achieve and the various lines of action and projects we plan to engage in within an 8-year framework, as well as a vision that goes far beyond 2020. Regardless of whether it is the next 10, 20 or 30 years we are looking at, we believe that it is vital, for a real difference to be made, for us to strive towards a city where nature and urbanity converge and enhance one another, where green heritage and green infrastructures lead to connectivity and continuity with the natural surroundings.

What king of green infrastructure and biodiversity do we seek in Barcelona?

We are not aiming for nature to form a map of isolated spots in the city; but rather, a genuine network of green areas or green spaces. We conceive this urban green as a green infrastructure and an inherent part of the city that would provide the maximum possible amount of environmental and social services and thereby increase the quality of life of the city’s residents.

Besides setting out an action plan, the Barcelona Green Infrastructure and Biodiversity Plan 2020 provides for a model of an urban green network and a city where green elements are not ornamental accessories but rather genuine green infrastructures. This model is based on two key concepts, connectivity and renaturalisation, and defined by two instruments:

• Urban green corridors, with the aim of becoming a real, robust and functional network of green infrastructures.

• Opportunity areas, of varying kinds and sizes, ranging from unoccupied plots to green roofs and balconies which can be identified in all neighbourhoods in Barcelona and are likely to undergo renaturalisation and revitalisation.

Urban green corridors, an ambitious approach for a greener Barcelona

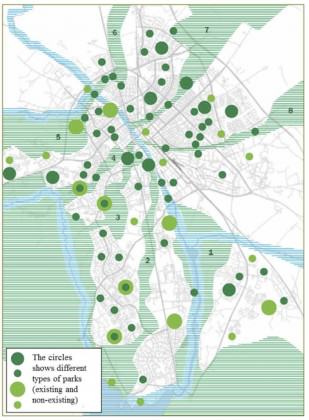

We in Barcelona see urban green corridors as city strips with a high concentration of vegetation, to be used exclusively—if not as a priority—by pedestrians and cyclists. These paths crossing the urban fabric are aimed at forming a functional green network to ensure connectivity not just between city’s various green spots but also between the entire metropolitan area of Barcelona, in particular the Collserola Mountain Range and the Llobregat and Besòs rivers.

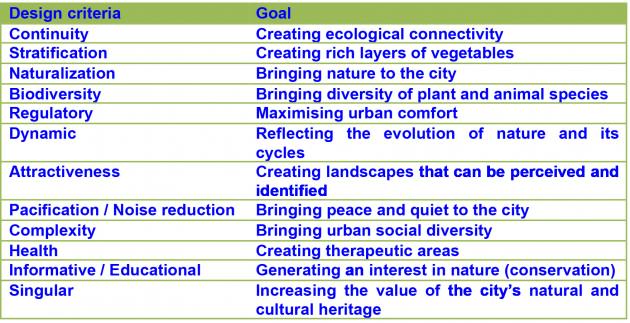

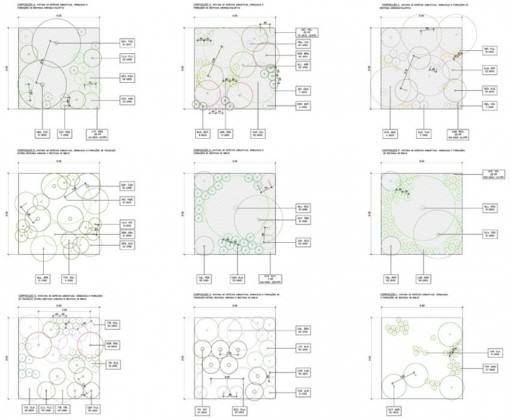

To succeed in implementing such an ambitious green-corridors programme, such urban planning and design will further need to incorporate both the complexity of nature and the natural elements’ processes if they are to provide more than just an “isolated” concept of urban green. The Barcelona City Council has published a guide for that very purposes, entitled “Urban Green Corridors. Examples and Design Criteria” (link in Catalan). It deals with a set of 12 main criteria that need to be taken into account when designing urban green corridors in a city such as Barcelona.

We know that it is no mean feat to make more room and connectivity for nature, and provide high-quality public spaces in a compact city such as Barcelona. It would have been demonstrably much easier if green corridors had been planned and created at the same time that other “grey” infrastructures were being developed. However with these goals in mind, we believe that all city makers—not just Barcelona but any other city around the globe—need to speed up such work if they are to reap the benefits as soon as possible of such urban green corridors and other nature-based solutions introduced to urban environments and offer an improved quality of life in our cities while preserving local&global nature.

about the writer

Glenn Stewart

Glenn Stewart is Professor of Urban Ecology, Lincoln University, NZ. Current research is on Southern Hemisphere urban ecosystems and invasive species, successional processes and predicted changes in global climate.

Glenn Stewart

Corridors have been promoted by conservation biologists to restore connectivity of habitats and to facilitate the movement of plants and animals. The exchange of genetic material between spatially distinct communities has a fundamental impact on ecological processes such as diversity-stability relationships, ecosystem function, and food webs.

But what evidence is there to support the efficacy of corridors? Well actually there is not much! If one looks at the empirical evidence from the published literature that supports (or otherwise) the utilization of corridors as conduits of biotic movement we see little evidence. As part of a graduate students thesis studies we reviewed literature from 11 scientific journals focussed on conservation, ecology, and landscape ecology from 1993-2010 and assessed the scientific evidence for corridor dispersal. Of 28 published experimental studies, 22 provided some evidence of dispersal. However, only 2 studies displayed scientific rigour i.e. they had clear and concise objectives, addressed confounding variables, utilized a “control” experiment, incorporated “replication”, used appropriate statistical analysis, discussed methodological limitations, described environmental conditions, presented data before and after habitat manipulation, included data on life history traits, and used “recorded” not inferred evidence. So although researchers might agree/promote corridors as beneficial there is little conclusive evidence from experimental studies that corridors increase dispersal of individuals between habitat patches.

So if they may or may not promote dispersal why do we promote their establishment?

Because they aesthetically look good, they harbour urban biodiversity and are relaxing to walk and/or cycle thru. We feel “good “about them. So for many social reasons they are great! On the other hand it may well be that they promote the movement of predators and exotic, invasive plants. Especially in many Southern Hemisphere “colonial countries” like New Zealand, Australia and South Africa. That is not good! So we have to achieve a balance between what is good and what is not! Corridors do provide a range of social and ecological services. In our neck of the woods “downunder” we promote “stepping stones” as a viable alternative. Why? Because a large proportion of our native trees and shrubs have fleshy fruits and are therefore bird dispersed and so many of our native (and exotic) birds freely distribute the seeds around the landscape. Which Is great! Although, unfortunately the same birds spread fleshy-fruited exotics! But the advantages probably outweigh the disadvantages. It is a conundrum!

about the writer

Marten Wallberg

Mårten Wallberg is President of Swedish Society for Nature Conservation the Stockholm Branch and also vice president of the national section of Swedish Society for Nature Conservation.

Marten Wallberg

This is very interesting questions and I will try to put them in the context of the Stockholm metropolitan area.

Stockholm County’s regional green structure constitutes ten green wedges and one of them is the Rösjö green wedge (Rösjökilen). These wedges stretch from the Stockholm city centre out into the surrounding rural landscape. Besides providing refuges for biodiversity in the urban landscape and spaces for a diversity of human activities, these large areas serve as green corridors connecting the green areas to a large-scale network throughout parts of the the region. However, the management of the green wedges are scattered among several municipalities with differing social and economical preconditions and that have monopoly of land use planning, which is a key challenge to their viability in the long-term perspective.

One way to solve the problem of how to make the wedges sustainable is to establish collaboration between the municipalities concerning the wedges. Let me give you an example of this.

The Rösjö green wedge presents a diversity of biotopes providing several ecosystem services, such as supporting urban biodiversity, mitigating climate change through local cooling effects, erosion and flood control, providing space for outdoor exercising and stress recovery, as well as education in ecology. The planning and formal management of the Rösjö green wedge is divided among six municipalities with limited incentives for cooperation, which risks causing fragmentation of the green wedge. In order to sustain the current and future values, collaboration is necessary as a strategy for policy development and institutional innovation. Since 2006 a collaboration of NGOs, municipalities, other authorities and universities has been developed.

The objectives for this initiative are: resilience, climate change adaptation, good living environment, increased accessibility and effective collaboration. A large number of meetings have been, and are, conducted with patience, trust and gaining approval as motto. The collaboration is dependent on sanctions from politicians and is organized around co-ordination groups and project groups. The main communication strategy was from the start outing guides, meetings with politicians and various media contacts. Currently politicians now sanction a platform for 2014-2020 and three more green wedges have joined the process. At the start of the collaborations my organization was the driving force but now the majors in each municipality comprise the steering committees for the collaborations. The collaborations is constantly being refined and analyses of the wedges concerning, among other things, ecosystem services and week ecological links are now being conducted. One of the aims of the analyses is to create a better tool for developing the region in a more sustainable way.

The point of considering these collaborations, as part of my answer to the questions asked, is to show the green corridors very actively can be a part of the urban development. Another point is that the collaboration makes politicians and policy makers in the different municipalities talk to each other, which is not always the case. Thus, the green wedges have not only ecological but also social and democratic functions.

I also want to point out that a close collaboration with Stockholm Resilience Centre at Stockholm University from the start has been a crucial part of the large collaboration.

about the writer

Na Xiu

Na Xiu, landscape architect and PhD student in Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala. Interested in how green and blue spaces in cities can be strongly connected, landscape history and theory in Scandinavia and China.

Na Xiu

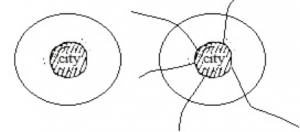

Whether green corridors work depends on how we, human beings, design and implement them. It is commonly accepted that green corridor should be based on habitat connection and also fulfill recreational, cultural and other social functions. For a corridor’s structure, green corridor is normally designed as linear pattern along the road and river systems. There are two common models in Chinese cities: surrounding and coupling. Both derive from an enclosed pie-shape city development and enclosed ring-road system but coupling pattern combines river or road system out of the city as well.

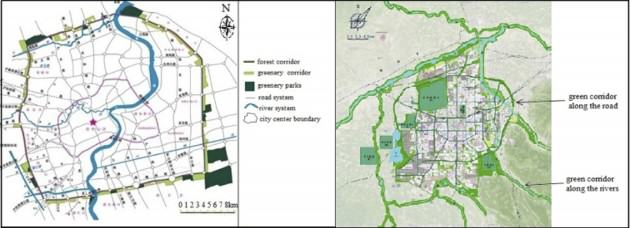

In Shanghai, an updated green corridor is still under construction. Based on ring-road system, the green corridor here is categorized as a two-fold meaning. The outer is the forest corridor, 100 meters wide with man-planted trees, which aims to build a stable environment for ecological communities. Besides it, a 400 meter wide greenery belt connects the productive nursery, memorial landscape, agricultural fields, wetland parks and so forth. Here, the green corridor is being implemented as two neighbors in order to provide both ecological and social functions. In terms of forest corridor, a variety of highly valued local trees and shrubs were planted with highly-controlled human management. The intention is to refer the structure of natural habitats and then build an artificial environmental community that lays a foundation for biodiversity and habitat conservation.

It is different from what we traditionally think of as a “Green Corridor”, which should focus on one (or several) species and link its habitats together. Until now, it has been difficult to judge whether it would be a good way or not, but a growing number of animals (birds and insects) were attracted for colonization, migration and interbreeding. At least it would be an available approach for severely interrupted and fragmented cities.

In Xi’an, city and regional plan of 2008-2020 emphasizes two parts of green corridor—along the ring-road system especially the loop expressway and along the river system. It is easy to see that the 3-122 meters wide green corridors along the road are still working like a belt because its enclosed ring-road system. The main function is to provide a good vision for traffic drivers. So the plan locates green corridor of road as Greenery.

But green corridor along the river system serves more like a typical “green corridor” that promote biodiversity and habitat connection. For quite a few years, habitat fragmentation of river system had been a city problem in Xi’an. In recent years, master plan started to reestablish the importance function of green corridors. But how to realize them? Restoring vegetation is the first step and the ongoing city plan of 2008-2020 is making efforts on that. Local trees, shrubs and grass are being selected and planted in the fragile river and nearby habitats to give them a chance to breathe.

When I consider how to define “green corridor” and how to implement them into practice, I would say it is difficult, especially in some fragmented Chinese cities. What we can see is that green corridor in Shanghai and Xi’an is still following the linear-shaped pattern along the road, river or any other linear-shaped elements of city areas.

As for how to make sure both ecological and social functions, the two cities give us a new idea—focusing on one aspect first. It means that when we design green corridors at the city scale, it should be based on a whole-city vision and select its main goal accordingly. In many Chinese cities, ring-road traffic is the current condition. So the priority is to recognize this and aim at social or ecological goals but not both. After one of these functions is fulfilled, the other one will be put on the agenda soon. Even as one of the functions is realized, the other may have been achieved already, who knows? The point is to focus success at specific goal first.

Target 1: “By 2020, at the latest, people are aware of the values of biodiversity and the steps they can take to conserve and use it sustainably.”

Target 1: “By 2020, at the latest, people are aware of the values of biodiversity and the steps they can take to conserve and use it sustainably.”  Target 2: “By 2020, at the latest, biodiversity values have been integrated into national and local development and poverty reduction strategies and planning processes and are being incorporated into national accounting, as appropriate, and reporting systems.

Target 2: “By 2020, at the latest, biodiversity values have been integrated into national and local development and poverty reduction strategies and planning processes and are being incorporated into national accounting, as appropriate, and reporting systems. Target 3: “By 2020, at the latest, incentives, including subsidies, harmful to biodiversity are eliminated, phased out or reformed in order to minimize or avoid negative impacts, and positive incentives for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity are developed and applied, consistent and in harmony with the Convention and other relevant international obligations, taking into account national socio‑economic conditions.”

Target 3: “By 2020, at the latest, incentives, including subsidies, harmful to biodiversity are eliminated, phased out or reformed in order to minimize or avoid negative impacts, and positive incentives for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity are developed and applied, consistent and in harmony with the Convention and other relevant international obligations, taking into account national socio‑economic conditions.” Target 4: By 2020, at the latest, Governments, business and stakeholders at all levels have taken steps to achieve or have implemented plans for sustainable production and consumption and have kept the impacts of use of natural resources well within safe ecological limits.

Target 4: By 2020, at the latest, Governments, business and stakeholders at all levels have taken steps to achieve or have implemented plans for sustainable production and consumption and have kept the impacts of use of natural resources well within safe ecological limits.  Target 5: By 2020, the rate of loss of all natural habitats, including forests, is at least halved and where feasible brought close to zero, and degradation and fragmentation is significantly reduced.

Target 5: By 2020, the rate of loss of all natural habitats, including forests, is at least halved and where feasible brought close to zero, and degradation and fragmentation is significantly reduced. Target 6: By 2020 all fish and invertebrate stocks and aquatic plants are managed and harvested sustainably, legally and applying ecosystem based approaches, so that overfishing is avoided, recovery plans and measures are in place for all depleted species, fisheries have no significant adverse impacts on threatened species and vulnerable ecosystems and the impacts of fisheries on stocks, species and ecosystems are within safe ecological limits.

Target 6: By 2020 all fish and invertebrate stocks and aquatic plants are managed and harvested sustainably, legally and applying ecosystem based approaches, so that overfishing is avoided, recovery plans and measures are in place for all depleted species, fisheries have no significant adverse impacts on threatened species and vulnerable ecosystems and the impacts of fisheries on stocks, species and ecosystems are within safe ecological limits. Target 7: By 2020 areas under agriculture, aquaculture and forestry are managed sustainably, ensuring conservation of biodiversity.

Target 7: By 2020 areas under agriculture, aquaculture and forestry are managed sustainably, ensuring conservation of biodiversity. Target 8: By 2020, pollution, including from excess nutrients, has been brought to levels that are not detrimental to ecosystem function and biodiversity.

Target 8: By 2020, pollution, including from excess nutrients, has been brought to levels that are not detrimental to ecosystem function and biodiversity. Target 9: By 2020, invasive alien species and pathways are identified and prioritized, priority species are controlled or eradicated, and measures are in place to manage pathways to prevent their introduction and establishment.

Target 9: By 2020, invasive alien species and pathways are identified and prioritized, priority species are controlled or eradicated, and measures are in place to manage pathways to prevent their introduction and establishment. Target 10: By 2015, the multiple anthropogenic pressures on coral reefs, and other vulnerable ecosystems impacted by climate change or ocean acidification are minimized, so as to maintain their integrity and functioning.

Target 10: By 2015, the multiple anthropogenic pressures on coral reefs, and other vulnerable ecosystems impacted by climate change or ocean acidification are minimized, so as to maintain their integrity and functioning. Target 11: By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water areas, and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes.

Target 11: By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water areas, and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscapes and seascapes. Target 12: By 2020 the extinction of known threatened species has been prevented and their conservation status, particularly of those most in decline, has been improved and sustained.

Target 12: By 2020 the extinction of known threatened species has been prevented and their conservation status, particularly of those most in decline, has been improved and sustained. Target 13: By 2020, the genetic diversity of cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals and of wild relatives, including other socio-economically as well as culturally valuable species, is maintained, and strategies have been developed and implemented for minimizing genetic erosion and safeguarding their genetic diversity.

Target 13: By 2020, the genetic diversity of cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals and of wild relatives, including other socio-economically as well as culturally valuable species, is maintained, and strategies have been developed and implemented for minimizing genetic erosion and safeguarding their genetic diversity.  Target 14: By 2020, ecosystems that provide essential services, including services related to water, and contribute to health, livelihoods and well-being, are restored and safeguarded, taking into account the needs of women, indigenous and local communities, and the poor and vulnerable.

Target 14: By 2020, ecosystems that provide essential services, including services related to water, and contribute to health, livelihoods and well-being, are restored and safeguarded, taking into account the needs of women, indigenous and local communities, and the poor and vulnerable. Target 15: By 2020, ecosystem resilience and the contribution of biodiversity to carbon stocks has been enhanced, through conservation and restoration, including restoration of at least 15 per cent of degraded ecosystems, thereby contributing to climate change mitigation and adaptation and to combating desertification.

Target 15: By 2020, ecosystem resilience and the contribution of biodiversity to carbon stocks has been enhanced, through conservation and restoration, including restoration of at least 15 per cent of degraded ecosystems, thereby contributing to climate change mitigation and adaptation and to combating desertification. Target 16: By 2015, the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization is in force and operational, consistent with national legislation.

Target 16: By 2015, the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization is in force and operational, consistent with national legislation. Target 17: By 2015 each Party has developed, adopted as a policy instrument, and has commenced implementing an effective, participatory and updated national biodiversity strategy and action plan.

Target 17: By 2015 each Party has developed, adopted as a policy instrument, and has commenced implementing an effective, participatory and updated national biodiversity strategy and action plan. Target 18: By 2020, the traditional knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, and their customary use of biological resources, are respected, subject to national legislation and relevant international obligations, and fully integrated and reflected in the implementation of the Convention with the full and effective participation of indigenous and local communities, at all relevant levels.

Target 18: By 2020, the traditional knowledge, innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, and their customary use of biological resources, are respected, subject to national legislation and relevant international obligations, and fully integrated and reflected in the implementation of the Convention with the full and effective participation of indigenous and local communities, at all relevant levels. Target 19: By 2020, knowledge, the science base and technologies relating to biodiversity, its values, functioning, status and trends, and the consequences of its loss, are improved, widely shared and transferred, and applied.

Target 19: By 2020, knowledge, the science base and technologies relating to biodiversity, its values, functioning, status and trends, and the consequences of its loss, are improved, widely shared and transferred, and applied. Target 20: By 2020, at the latest, the mobilization of financial resources for effectively implementing the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 from all sources, and in accordance with the consolidated and agreed process in the Strategy for Resource Mobilization, should increase substantially from the current levels. This target will be subject to changes contingent to resource needs assessments to be developed and reported by Parties.

Target 20: By 2020, at the latest, the mobilization of financial resources for effectively implementing the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 from all sources, and in accordance with the consolidated and agreed process in the Strategy for Resource Mobilization, should increase substantially from the current levels. This target will be subject to changes contingent to resource needs assessments to be developed and reported by Parties.

We’re clever creatures. Thanks to computer-generated imagery even the most run-of-the-mill children’s animated feature movie can contain astonishingly convincing pictures of landscapes, plants and creatures. Imaginary landscapes have become routinely realistic, and for that we have to thank

We’re clever creatures. Thanks to computer-generated imagery even the most run-of-the-mill children’s animated feature movie can contain astonishingly convincing pictures of landscapes, plants and creatures. Imaginary landscapes have become routinely realistic, and for that we have to thank  But like all kinds of revolutionism it had trouble distinguishing babies from bathwater and its followers tended to distill subtle ideas into slogans and often seemed to get the wrong end of the stick. Whereas progressive modernist architects like the inimitable

But like all kinds of revolutionism it had trouble distinguishing babies from bathwater and its followers tended to distill subtle ideas into slogans and often seemed to get the wrong end of the stick. Whereas progressive modernist architects like the inimitable

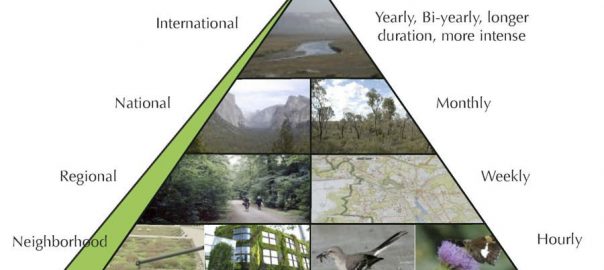

Readers of this blog would all most likely agree that a meaningful connection with nature is vital to human well-being but is that something that cities can really deliver? Parklands and green public spaces do introduce something of that connection—wildflower meadows more than manicured lawns, perhaps—but a prohibition against too many people stepping on the grass becomes an essential part of the management strategy when population numbers and density begin to rise. The scale of the city is key.

Readers of this blog would all most likely agree that a meaningful connection with nature is vital to human well-being but is that something that cities can really deliver? Parklands and green public spaces do introduce something of that connection—wildflower meadows more than manicured lawns, perhaps—but a prohibition against too many people stepping on the grass becomes an essential part of the management strategy when population numbers and density begin to rise. The scale of the city is key.

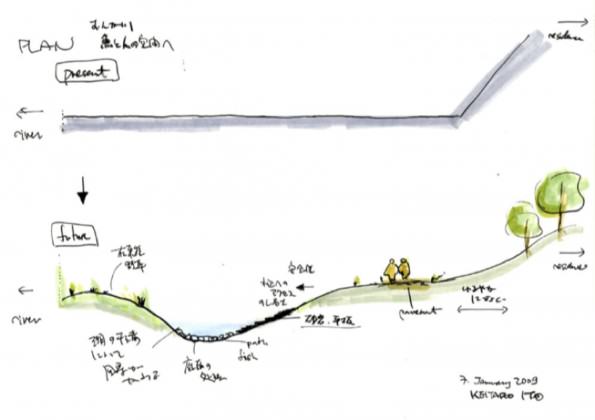

On the surface, this idea seems to remove any reason for worrying about nature within a city. But if we look a bit deeper, we see that Kawaguchi’s perspective also unveils something more rooted; it shows us a framework wide enough to allow the sacred to enter everyday life.

On the surface, this idea seems to remove any reason for worrying about nature within a city. But if we look a bit deeper, we see that Kawaguchi’s perspective also unveils something more rooted; it shows us a framework wide enough to allow the sacred to enter everyday life.

Make identity apparent

Make identity apparent

Over the last twenty years Israel has undertaken a railway revolution, modernizing and expanding the system that was built originally as part of the vision of the Ottoman Empire in the nineteenth century, which established direct rail communication from Alexandria in Egypt to Damascus in Syria. The Turkish North-South grid always included Jerusalem in its itineraries. In the recent years of train revival the railway has become the main mode of transport for more than one and a half million Israelis, taking some of the strain off the main highways, and helping to reduce pollution in our cities.

Over the last twenty years Israel has undertaken a railway revolution, modernizing and expanding the system that was built originally as part of the vision of the Ottoman Empire in the nineteenth century, which established direct rail communication from Alexandria in Egypt to Damascus in Syria. The Turkish North-South grid always included Jerusalem in its itineraries. In the recent years of train revival the railway has become the main mode of transport for more than one and a half million Israelis, taking some of the strain off the main highways, and helping to reduce pollution in our cities. While the steam train was running, it cut through the Jerusalem neighborhoods that had developed in the Southern part of the city after the original track had been laid.

While the steam train was running, it cut through the Jerusalem neighborhoods that had developed in the Southern part of the city after the original track had been laid. The eight-kilometer promenade is used by people of all ages and cultures, practically round the clock. They enjoy the clean air, quiet, social interaction and beauty of the Railway Park. Wheelchairs, baby strollers, joggers and bikers all benefit from an enjoyable and accessible walk/run/skate/ride. The park is also playing an important role in protecting urban biodiversity, since it serves as an ecological corridor linking the chain of inner city parks and gardens to the southern section of the ring of metropolitan parks surrounding the built perimeter of Jerusalem.