Kim Behrens and I are driving slowly through my Turnagain neighborhood on a snowy mid-December afternoon, when a legion of songbirds prompts us to pull over to the curb, grab binoculars, and scramble out of her truck. In deepening grayness, we stand in open-mouthed amazement among yards that have been ornamented with mountain ash and other fruit trees. In those trees and the sky overhead are dozens of robins and more than a thousand bohemian waxwings.

Only minutes before, Kim and I had finished walking a section of Anchorage’s Coastal Trail. We covered 4½ miles in 3½ hours, while shuffling through the snow at an intentionally slow pace. Participants in Anchorage’s annual Christmas Bird Count (CBC), we stopped frequently to look and listen for birds. During the first hour of our walk we counted nearly 20 black-capped chickadees, several magpies and ravens, a few mallards, a red-breasted nuthatch and hairy woodpecker, and hundreds of waxwings, seven species in all. But what began as a light snow became heavy by mid-day and the birds seemed to disappear. By hike’s end we remained stuck on seven species, with nothing unusual to report.

Now, passing through another CBC team’s area, we don’t concern ourselves with counting birds, only enjoying their presence and wondering if we’ll spot a local rarity, a dusky thrush that’s been reported hanging out with the robins, which in recent years have overwintered in Anchorage in steadily growing numbers.

We don’t see the rare thrush, but that’s okay. I’m simply delighted to be in the company of so many robins; we’re surrounded by several dozen of them, the most I’ve ever encountered at one time, by far. Later I’ll learn that one group of CBC participants counted a flock of 90 robins—ninety!—a number that seems remarkable to me. Hunkered down among clusters of mountain ash berries, the robins are spectacle enough. But the waxwings add to our pleasure. Well over a thousand of them swoop and circle through the neighborhood, landing on trees and then lifting off again with a great and startling whoomph.

Eventually more Christmas Bird Counters arrive and put binoculars to eyes, still hoping to see that dusky thrush among the many robins. Residents shoveling their driveways seem as curious about us as the swirling, berry gobbling birds we’re watching and a group leader takes the opportunity to explain why we’re out here, what we’re doing.

The evening of Dec. 14, a few dozen birding enthusiasts gather for the local CBC tally, feasting on the chili, corn bread, and desserts that are part of the ritual. The crowd is smaller than usual because of the storm, but there’s plenty of enthusiasm and laughter as the day’s results are reported and stories are shared.

The final count: only thirty species, a low number attributed at least in part to the weather. Most years around 40 species are observed and in 1984 an Anchorage record 52 species were counted. No group saw more than fourteen species and most counters observed ten species or less.

Among the surprises: only one owl (a boreal) was seen or heard and only 64 pine grosbeaks and 72 common redpolls were counted, way below average. The redpoll number was especially surprising; last winter, legions of them invaded Anchorage and the local CBC record is 7,917 birds. But redpolls are known for their great swings in numbers from year to year as flocks of them search the northern landscape for food. On the high side of things, nearly 19,000 waxwings (below the record of 22,245, but certainly impressive) and a record 304 robins were counted.

The final human tally was 51 feeder watchers and only 82 field observers. That too is low, organizers tell me. Again, weather likely kept numbers down in this, Anchorage’s 53rd holiday count.

* * *

There are any number of ways that urban residents can become more engaged with their surroundings and wild neighbors, and citizen science—which has been described as “public participation in scientific research”—can be an especially effective way of doing so. Perhaps because birds are so ubiquitous, many of the largest, longest lasting, and most popular citizen science efforts are tied to our winged neighbors. And there’s no better example than the Christmas Bird Count. Organized by the National Audubon Society in coordination with its regional and local chapters, the CBC is reported to be the world’s longest-running citizen science survey. Now 114 years old, in recent years it has attracted tens of thousands of participants, who gather information that is added to an ever-expanding database. That data then helps ornithologists and other scientists to track long-term population trends.

As the Audubon Society recounts on its website, the CBC’s origins can be traced to an earlier holiday tradition known as the Christmas “side hunt.” Participants would choose sides and then go hunting for birds; whichever team brought in the biggest pile of feathered (and apparently furred) bodies, won the competition. In 1900, ornithologist Frank Chapman of the fledgling Audubon Society proposed a new holiday ritual: a Christmas Bird Census that would encourage people to count birds during the holiday season, rather than kill them. Chapman and 27 others participated in that initial census, which included 25 count areas spread from Toronto, Ontario to Pacific Grove, California (though most were in the northeast United States). Together they tallied 90 species.

By the 2012-2013 count (the most recent for which complete data is available), the number of count areas had increased to a record 2,369 locales while the number of individual observers reached 71,231 people, also a record. The great majority of those count areas are in the U.S., but hundreds more are spread through Canada, Latin America, the Caribbean, and several Pacific islands. (Anchorage’s first-ever Christmas count occurred in 1941, when a single resident went looking for birds, but then two decades passed before a second count was organized, that time with eighteen participants. It has been staged every year since then but once.)

The Audubon Society and other Christmas Bird Count advocates emphasize that data collected by participants over the past 114 years has helped “researchers, conservation biologists, and other interested observers to study the long-term health and status of bird populations across North America [and now other areas]” while providing “a picture of how the continent’s bird populations have changed in time and space over the past hundred years.”

But the CBC and other citizen-science efforts also help to make people more aware of the creatures with which we share the landscape, including and especially urban residents who might normally ignore their presence. Besides the scores of people who participate in Anchorage’s count, for example, thousands more residents are made aware of which birds share our city through the Anchorage Audubon’s website and emails to its members, and also through local media coverage of the event. This is no small thing, especially in winter, when people tend to spend most of their time indoors and give less thought to the animals that share our cities and the habitat that they depend upon. What better way to remind the general public that we human residents of Anchorage share the winter landscape with more than ravens, chickadees, waxwings, and rock doves (the latter better known as pigeons)?

* * *

While the Christmas Bird Count is the longest running bird-oriented citizen science project, in recent decades other events and programs have greatly expanded people’s awareness of the wild birds that live among us, even in the most urban of locales. Later this month, tens of thousands of people around the world will participate in the seventeenth annual Great Backyard Bird Count. Organized by the National Audubon Society and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the GBBC is a four-day happening that this year begins on Friday Feb. 14 and runs through Monday, Feb. 17.

As explained on the website, this event is intended to engage “bird watchers of all ages in counting birds to create a real-time snapshot of bird populations. Participants are asked to count birds for as little as 15 minutes (or as long as they wish) . . . Anyone can take part in the Great Backyard Bird Count, from beginning bird watchers to experts, and you can now participate from anywhere in the world.”

What makes the GBBC especially effective is this sense of inclusiveness (no special expertise required); the fact that participants don’t have to invest a great deal of time or effort (you can watch bird feeders from the comfort of your home for as little as 15 minutes a day); and the ease of reporting data (at least for those with access to a computer and basic Internet skills). Also appealing in our “instant gratification” times and culture is the fact that participants can check out “real-time maps and charts that show what others are reporting during and after the count.” If that isn’t enough, all participants are entered in a drawing, with the chance of winning prizes that range from bird feeders and books to binoculars. Such a deal!

There’s also the sense of joining a grand event in which people scattered around the world are increasing our knowledge of birds, while helping researchers “learn more about how birds are doing, and how to protect them and the environment we share.”

In short, the organizing partners explain, “It’s free, fun, and easy.” That’s true no matter where you live, including the innermost parts of cities.

This approach has proved highly successful. In 2013, GBBC participants turned in more than 134,000 checklists (many submitted daily reports for each of the four days) with some 34.5 million individual bird observations, representing 4,004 species, including a record 638 species in the United States. Event organizers received checklists from 111 countries and territories, representing all seven continents. In total, the 2013 GBBC provided “the most detailed four-day snapshot of global bird populations ever undertaken.”

Aside from all the data and whatever help it provides to researchers and managers, the GBBC, like the Christmas Bird Count, also engages significant numbers of people—many of them urban residents—in a citizen science effort that invites people to pay increased attention to their wild neighbors and the landscapes we share with birds.

Complimenting the Christmas Bird Count and Great Backyard Bird Count are two other popular programs that present great opportunities for both urban and rural bird enthusiasts throughout the United States and beyond. One of them is seasonal, the other year-round.

Another “fun and easy” citizen-science program of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Project FeederWatch is, like the GBBC, intended for people of “all skill levels.” Now in its 27th season, FeederWatch enlists the help of birding enthusiasts throughout the winter season (from early November into April). Participants keep track of the birds that come into their feeders two days per week and report their observations. Again, it’s an ideal opportunity for people to connect with birds—and the larger world of nature—wherever they live.

The year-round program is ebird. Another cooperative Audubon-Cornell Lab effort, ebird was started in 2002 and its primary goal is to utilize the “vast number of bird observations made each year by recreational and professional bird watchers.”

At various times, I have participated in all of the programs mentioned here while living in Alaska’s urban center. I know firsthand that each citizen science effort, in its own way, provides opportunities for people to pay increased attention to the birds with which we share our home landscapes and to learn more about them.

Because many species adapt to urban environments and they’re often more easily noticed than other forms of wildlife, birds—and programs like those described here—can be ideal portals into a greater appreciation and increased awareness of the wild nature that exists in cities. They’re most valuable during the winter season, especially in northern climes, where darkness and cold make it easy to stay indoors and be less attentive to the wildness and natural wonders that enliven our cities throughout the year.

Bill Sherwonit

Anchorage

What Does Urban Nature-Related Graffiti Tell Us? A Photo Essay from the City of Cape Town

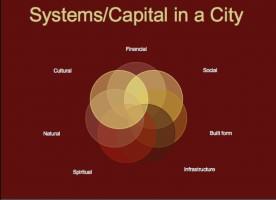

What Does Urban Nature-Related Graffiti Tell Us? A Photo Essay from the City of Cape Town Wicked Problems, Social-ecological Systems, and the Utility of Systems Thinking

Wicked Problems, Social-ecological Systems, and the Utility of Systems Thinking A Worldview of Urban Nature that includes “Runaway” Cities

A Worldview of Urban Nature that includes “Runaway” Cities Open Mumbai: Re-envisioning the City and Its Open Spaces

Open Mumbai: Re-envisioning the City and Its Open Spaces A Comic Book Sparks Kids Toward Environmental Justice

A Comic Book Sparks Kids Toward Environmental Justice Cities as Refugia for Threatened Species

Cities as Refugia for Threatened Species “Growing Place” in Japan—Creating Ecological Spaces at Schools that Educate and Engage Everyone

“Growing Place” in Japan—Creating Ecological Spaces at Schools that Educate and Engage Everyone Architecture and Urban Ecosystems: From Segregation to Integration

Architecture and Urban Ecosystems: From Segregation to Integration Urbanophilia and the End of Misanthropy: Cities Are Nature

Urbanophilia and the End of Misanthropy: Cities Are Nature Re-imagining Nairobi National Park: Counter-Intuitive Tradeoffs to Strengthen this Urban Protected Area

Re-imagining Nairobi National Park: Counter-Intuitive Tradeoffs to Strengthen this Urban Protected Area Up the Creek, With a Paddle: Urban Stream Restoration and Daylighting

Up the Creek, With a Paddle: Urban Stream Restoration and Daylighting It Is Time to Really “Green” the Marvelous City

It Is Time to Really “Green” the Marvelous City Lessons from a One-eyed Eagle

Lessons from a One-eyed Eagle

Thus, the importance of cities living in harmony with nature has been emphasised. The ancient Indian science

Thus, the importance of cities living in harmony with nature has been emphasised. The ancient Indian science

Somehow it seems fitting that a one-eyed eagle calls this place home. By all rights, the island should have been paved over long ago. Despite the odds, it somehow survived, decade after decade as the landscape around it developed. The odds are against it now too. The big money and conventional wisdom say development is inevitable — we need to prepare for the future. But sometimes the conventional wisdom is wrong; sometimes we need to think beyond the experts or perhaps seek out different sources of wisdom. Sometimes the path forward is written not in technical reports, but on the side of a canoe and in the stories of our fellow travelers, the stories that usually don’t make it into technical reports.

Somehow it seems fitting that a one-eyed eagle calls this place home. By all rights, the island should have been paved over long ago. Despite the odds, it somehow survived, decade after decade as the landscape around it developed. The odds are against it now too. The big money and conventional wisdom say development is inevitable — we need to prepare for the future. But sometimes the conventional wisdom is wrong; sometimes we need to think beyond the experts or perhaps seek out different sources of wisdom. Sometimes the path forward is written not in technical reports, but on the side of a canoe and in the stories of our fellow travelers, the stories that usually don’t make it into technical reports.

The following two examples depict boats tossing in stormy seas, a strong narrative of shared, collective history in Cape Town, which was originally known as the Cape of Storms. Even today ships run aground on the shores of the City every winter and this is an aspect of nature we all share and respect.

The following two examples depict boats tossing in stormy seas, a strong narrative of shared, collective history in Cape Town, which was originally known as the Cape of Storms. Even today ships run aground on the shores of the City every winter and this is an aspect of nature we all share and respect.

Pictures of African wildlife, not present in Cape Town for hundreds of years, litter the city, calling on the larger urban populations to take up these distant conservation causes.

Pictures of African wildlife, not present in Cape Town for hundreds of years, litter the city, calling on the larger urban populations to take up these distant conservation causes.

The following graffiti is regularly updated, keeping abreast of the shocking rhino death tolls due to poaching for the illegal horn trade in conservation areas far flung from Cape Town.

The following graffiti is regularly updated, keeping abreast of the shocking rhino death tolls due to poaching for the illegal horn trade in conservation areas far flung from Cape Town.

In addition to the main city presentations on Thursday and Friday, there were a number of side events, earth walks, and workshops for participants and the general public. These includes walking tours of the Dell Stream Day-lighting project on the UVA Grounds and the Meadow Creek Stream Restoration Project (in the City of Charlottesville,

In addition to the main city presentations on Thursday and Friday, there were a number of side events, earth walks, and workshops for participants and the general public. These includes walking tours of the Dell Stream Day-lighting project on the UVA Grounds and the Meadow Creek Stream Restoration Project (in the City of Charlottesville,  One of my favorite events had to do with ants. We were joined for most of the launch by an entomology post-doc from North Carolina State University, Amy Savage. On Friday, during the bulk of our presentations from partner cities, Amy was busy setting out ant bait (including such things as Snickers bars, tuna, and pecan Sandies), attempting to see just how many species of ants she might find in and around the UVA School of Architecture. She was quite successful and discovered 13 different species in short order, in close proximity to where we were meeting. Education about this ant diversity, the habitat we were sharing that day, became something we attempted to weave into the more formal meeting and power point presentations. With Amy’s help at several points during the day we interrupted the Launch presentations with a report on what species had been found. We also produced a series of five ant collecting cards, with images of ant genus on one side and information about biophilic cities on the other side.

One of my favorite events had to do with ants. We were joined for most of the launch by an entomology post-doc from North Carolina State University, Amy Savage. On Friday, during the bulk of our presentations from partner cities, Amy was busy setting out ant bait (including such things as Snickers bars, tuna, and pecan Sandies), attempting to see just how many species of ants she might find in and around the UVA School of Architecture. She was quite successful and discovered 13 different species in short order, in close proximity to where we were meeting. Education about this ant diversity, the habitat we were sharing that day, became something we attempted to weave into the more formal meeting and power point presentations. With Amy’s help at several points during the day we interrupted the Launch presentations with a report on what species had been found. We also produced a series of five ant collecting cards, with images of ant genus on one side and information about biophilic cities on the other side. The incorporation of ants provided a visceral demonstration on the ways in which nature, much of it small and difficult to see, is all around us in cities. There is immense wonder and fascination value in ants, of course, yet urbanites are not well educated in looking for, identifying or even visualizing their existence all around us. Amy works with a wonderful initiative called the School of Ants that seeks to engage citizens in the collection and identification of ants throughout the country. They have produced a highly valuable urban

The incorporation of ants provided a visceral demonstration on the ways in which nature, much of it small and difficult to see, is all around us in cities. There is immense wonder and fascination value in ants, of course, yet urbanites are not well educated in looking for, identifying or even visualizing their existence all around us. Amy works with a wonderful initiative called the School of Ants that seeks to engage citizens in the collection and identification of ants throughout the country. They have produced a highly valuable urban  On Saturday afternoon, Amy took the ant station, including her microscope, to the Charlottesville Downtown Mall, engaging children and families walking by about the ants around them—something we called the Urban Ant Safari! In her interactions with people on the downtown mall Amy asked people to write down memories and recollections they had about ants in their past. She later compiled and shared these with us, and some were quite moving. An older woman wrote a note about her days as a child in England during WWII. She wrote, ‘When I was an evacuated little girl of 5 in WWII Britain, I used to watch ants. I dreamed of having a see through container, so that I [could] watch them work.’

On Saturday afternoon, Amy took the ant station, including her microscope, to the Charlottesville Downtown Mall, engaging children and families walking by about the ants around them—something we called the Urban Ant Safari! In her interactions with people on the downtown mall Amy asked people to write down memories and recollections they had about ants in their past. She later compiled and shared these with us, and some were quite moving. An older woman wrote a note about her days as a child in England during WWII. She wrote, ‘When I was an evacuated little girl of 5 in WWII Britain, I used to watch ants. I dreamed of having a see through container, so that I [could] watch them work.’

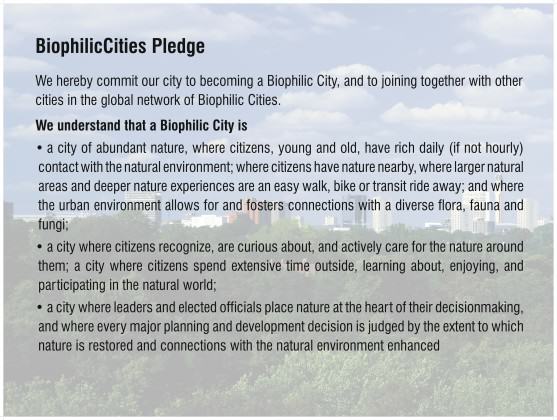

On Saturday morning a smaller group, mostly partner city representatives, came together to participate in a workshop to discuss and invent the new global Biophilic Cities Network. For several hours we discussed and debated key questions about what the Network could or should look like, what functions it will serve, what value it will have, and how and in what ways it might meet needs not served by other networks that exist.

On Saturday morning a smaller group, mostly partner city representatives, came together to participate in a workshop to discuss and invent the new global Biophilic Cities Network. For several hours we discussed and debated key questions about what the Network could or should look like, what functions it will serve, what value it will have, and how and in what ways it might meet needs not served by other networks that exist.

One of the most useful parts of our discussion had to do with what value of such a global network and how it would serve to strengthen the position of those in and outside city government working in support of nature. Some participants emphasized the importance of different local departments breaking out of their silos and that the network might help to do this. Others noted that the pledge card seemed to envision participants and signatories as primarily local council or local governments, but that left out universities, NGOs and many others with a stake in the network but working outside the city government.

One of the most useful parts of our discussion had to do with what value of such a global network and how it would serve to strengthen the position of those in and outside city government working in support of nature. Some participants emphasized the importance of different local departments breaking out of their silos and that the network might help to do this. Others noted that the pledge card seemed to envision participants and signatories as primarily local council or local governments, but that left out universities, NGOs and many others with a stake in the network but working outside the city government.

3 Comments

Join our conversation