Introduction

about the writer

Chris Fremantle

Chris Fremantle is a producer and research associate with On The Edge Research, Gray’s School of Art, The Robert Gordon University. He produces ecoartscotland, a platform for research and practice focused on art and ecology for artists, curators, critics, commissioners as well as scientists and policy makers.

about the writer

Anne Douglas

Anne Douglas is a Professor Emeritus, previously Chair in Art in Public Life at the Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen Scotland. She has focused, over the past 25 years, on developing doctoral/postdoctoral research into the changing nature of art in public life, increasingly in relation to environmental change.

The Harrisons (Helen Mayer Harrison (1927-2018) and Newton Harrison (1932-2022) are widely acknowledged as pioneers in bringing together art and ecology into a new form of practice. They worked for over fifty years with biologists, ecologists, architects, urban planners, and other artists to initiate collaborative dialogues. The works they made in various places from the second half of the 1970s stand as proposals for putting the well-being of the web of life first. The Harrisons’ visionary projects have, on occasion, led to changes in governmental policy and have expanded dialogue around previously unexplored issues leading to practical implementations variously in the United States, Europe, and Asia.

In writing and inviting people to contribute we sought advice and received extensive help from both the Harrison Studio/Center for the Study of the Force Majeure (CFM); from Kai Resche and Petra Kruse, curators and editors with the Harrisons (and also the Berlin branch of CFM), as well as from David Haley (who was the project manager for Casting a Green Net and Associate artist for Greenhouse Britain: Losing Ground, Gaining Wisdom (2007-09).

We offer the following passage from one of the Harrisons perhaps less well-known works as a prompt, encapsulating their approach:

Trümmerflora, or rubble plants and trees, are a special phenomena unique to heavily bombed urban areas. The bomb acts as a plough, breaking brick, mortar, metal, and wood into fragments and, in a single gesture, mixing these with earth from below. The earth often contains seeds, dormant from the time of first construction on the site, that may have been buried for a century or more. These seeds come to light, and those that can live in this new and special earth, grow and flourish. Other seeds, dropped by wind and by animals, also survive in limited numbers in this new soil, this rubble. Hence the name Trümmerflora, or loosely translated, rubble flowers.

Harrison and Harrison 1990 ‘Trümmerflora: on the Topography of Terrors’ in Polemical Landscapes California Museum of Photography pp 12-13

This 1988 work by Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison during a period of residency in Berlin emerged in response to overlooking the derelict site that had been the headquarter of the Gestapo, Storm Trooper, and Secret Service Operations, i.e. the bureaucratic center for the Death Camps and Labour Camps of the Nazi regime. Earlier attempts by others to create an appropriate monument or memorial to the horrors of this urban site had failed. As Jewish people, this site was hugely significant. However, the Harrisons characteristically turned their attention to a possibility of healing brought about through an ecological understanding of the site, creating a proposal that enfolds this history, the destruction of the infrastructure of terror reducing it to rubble, lending itself to new life through the forces of nature.

The contributors to this round table, including artists, curators, environmentalists, landscape architects, and scientists, have all reflected on what they learned from meeting and working with the Harrisons. For some, this starts with Portable Fish Farm: Survival Piece #III which caused a furore when it was exhibited at the Hayward Gallery in London in 1971. A number of others were involved in various ways (curator, environmentalist, scientist, artist, and project manager) with the Harrisons’ work Casting a Green Net: Can it be we are seeing a Dragon? (1998) made as part of ‘ArtTranspennine98’, a major regional collaboration between the Tate Gallery Liverpool and the Henry Moore Sculpture Trust. Others have much more recent experiences of Newton Harrison as he continued the practice, including curating an exhibition Eco-art Work: 11 Artists from 8 Countries for Various Small Fires in Los Angeles in 2022, and developing the work Sensorium.

Contributors reflect on how working with the Harrisons in various different ways informed, changed, and developed their practices. Some talk about having the strictures of their respective disciplines and working practices lifted and their thinking transformed. Others talk about the love, the love between the Harrisons, and the wider empathy reaching beyond human-centredness that they engendered.

Click here for a more in-depth reflection regarding this roundtable.

Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison

about the writer

Helen & Newton Harrison

Helen Mayer Harrison (1927-2018) and Newton Harrison (1927-2018) were artists that pioneered art and ecology, developing an approach that characterised them also as educators. In their artworks, the Harrisons collaborated with planners, scientists, and communities on bioregional scale projects addressing ecosystem health in the context of climate change and the need for adaptation. Helen brought a perspective from her deep knowledge of literature, psychology, and education. She had held senior roles in Higher Education before beginning to collaborate with Newton. He had studied visual art and was already an acclaimed artist before beginning to collaborate with Helen. Their life's work wove together these different knowledges and experiences, generating a unique and appropriate aesthetic that addressed the wellbeing of the web of life.

Scotland becomes the first country in the history of countries

to intentionally give back more to the life web than it consumes

when the deep wealth of the country is understood

to be in part a vast commons, with the topsoil as vital

The wealth becomes magnified when the topsoil is attended to

beginning by transforming all organic waste into humus

and continuing the regenerating of carbon in the topsoil mat

while banning all inorganic fertilizer

The deep wealth of the country is maintained

by the oxygen that trees give forth

and the COy the trees and all green growing things sequester

When COg sequestering lowers the atmospheric CO2

and the oxygen production is greater than the consumption

the wealth in the atmospheric commons of the country grows

True for all culturally generated CO2 production

but also true for the breath of the 5.3 million people in Scotland

that requires some 1500 square miles of open canopy forest

Assuming 70 trees per acre or 30 trees per person

to compensate simply for the privilege of breathing

Breathing in the country and the consumption of oxygen

and the production of COy equalize as the forest matures

Thereafter wealth grows as the forest commons grow

The moment is urgent….if business as usual continues

Scotland as usual will continue to have

a carbon footprint over three times its physical size

to do nothing risks the death of the life web

to do too little risks near death and a sixth extinction

to do enough we cannot know without the doing of it

The wealth of the country is in its waters especially the rainfall

about 113 cubic kilometers fall a year on average on these lands

If the excess waters that form the aquatic commons of the nation

are redirected into an array of estuarial lagoons

or into drought ridden farming areas

or into bogs and small lakes and wetlands

The redirection expressed in new food that is produced

also the biodiversity of the country increases

and the cost of flood control decreases

So increases the deep wealth of the nation

When the wealth of the Scottish nation becomes great enough

to trade for what it cannot produce

and this wealth springs from the life web in such a way

that the web’s overproduction is harvested

the harvest preserves and can even enhance the system

It is in this way that Scotland becomes

the first nation in the history of nations

to generate its deep wealth ecologically

tuned to the original peoples’ life ways

and the delusion of an invisible hand disappears

The deep wealth of this nation can grow exponentially

when agreement is found in a majority of its 5,300,000 population

to gain a collective responsibility for the well working of the life web

sufficient to stimulate the web to overproduce

in ways that advantage the web and advantage the human community

Scotland has this opportunity

appearing most clearly in the relationship of a modestly sized educated population

to the 30,000 square miles of land variously available

coupled with an initial unity of beliefs at work

Scotland can become the first modern country to stimulate

then put to work the overproduction of the life web as vast public good

In so doing also becoming the first people in modern history

to reach an ecologically informed commons of mind itself a Meganiche

among the multimillion species that nest within the great web of life.

Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison

about the writer

Helen & Newton Harrison

Helen Mayer Harrison (1927-2018) and Newton Harrison (1927-2018) were artists that pioneered art and ecology, developing an approach that characterised them also as educators. In their artworks, the Harrisons collaborated with planners, scientists, and communities on bioregional scale projects addressing ecosystem health in the context of climate change and the need for adaptation. Helen brought a perspective from her deep knowledge of literature, psychology, and education. She had held senior roles in Higher Education before beginning to collaborate with Newton. He had studied visual art and was already an acclaimed artist before beginning to collaborate with Helen. Their life's work wove together these different knowledges and experiences, generating a unique and appropriate aesthetic that addressed the wellbeing of the web of life.

From Peninsula Europe: The High Ground – Bringing Forth a New State of Mind 2002

Is Peninsula Europe at a bifurcation point?

At a point of change and self-transformation?

After all, from the Romans through the Middle Ages

through the Renaissance

the Enlightenment

from Modernity to the Now,

that territory we call Europe

has many times rebuilt its landscape

economically, politically, culturally.

It has rebuilt its belief systems

and rebuilt its ecosystems.

Now we imagine a new set of emergent properties

suggesting that this is indeed a bifurcation point in a state of

becoming

a point of reorganisation of its own complexities

into a new form of entityhood.

If so

Peninsula Europe becomes the center of a world.

Peninsula Europe moves towards entityhood

when its boundary conditions become

more permeable

to what it understands

as contributing to its wellbeing

and

less permeable

to what does not.

Peninsula Europe moves towards entityhood

when its discourse

can focus on the carrying capacity of its terrains

for industry, farming, fishing

information production

and cultural divergence.

Peninsula Europe moves towards entityhood

as it transforms its wastes

into that which is useful and valuable

while successively reducing the wastes

that are damaging to itself

and when

its organic waste disposal

becomes a vast topsoil regenerating system

insuring green farming

remodeling its food production systems

on natural systems.

Peninsula Europe moves towards entityhood

when its river systems, estuaries, ocean edges,

forests, wetlands, meadowlands, and eco-corridors

are valued sufficiently

and enabled to co-join

into a complex biodiverse life web

self-sustaining in nature

an eco-net of the whole

and its high ground, grassland, and forest communities

contribute ecological redundancy, continuity, and mass

at a continental scale.

Peninsula Europe moves towards entityhood

which its diversity of cultures is protected

and they are valued for themselves

and are encouraged to be seen as self-creating entities

adding improvisation and creativity

diversity and uniqueness to the cultural web.

Entityhood happens when each part feeds value to the whole

and the whole complicates itself

following the natural laws of self-organization

and creating a complex entity.

Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison

about the writer

Helen & Newton Harrison

Helen Mayer Harrison (1927-2018) and Newton Harrison (1927-2018) were artists that pioneered art and ecology, developing an approach that characterised them also as educators. In their artworks, the Harrisons collaborated with planners, scientists, and communities on bioregional scale projects addressing ecosystem health in the context of climate change and the need for adaptation. Helen brought a perspective from her deep knowledge of literature, psychology, and education. She had held senior roles in Higher Education before beginning to collaborate with Newton. He had studied visual art and was already an acclaimed artist before beginning to collaborate with Helen. Their life's work wove together these different knowledges and experiences, generating a unique and appropriate aesthetic that addressed the wellbeing of the web of life.

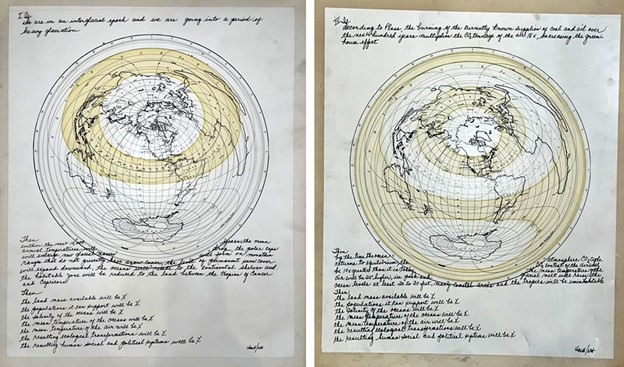

From Greenhouse Britain: Losing Ground, Gaining Wisdom 2007

The news is not good and it is getting worse

And for this island

Which is a much loved place

the news is not good and is getting worse

For instance

The Greenland Ice Shelf is breaking up

more rapidly than anyone thought

and this alone could cause an ocean rise

of up to 7 metres

Looking at the first two metre rise

Looking at the storm surge thinking about protection

thinking about where monies might come from

to protect land and people

The news is not good and it’s getting worse

animals are on the run plants are migrating

if the temperatures on the average

rise above 2 degrees Celsius one scenario predicts

Europe, Asia, America, and the Amazon

will lose 30 percent of their forests with concomitant extinctions

Looking at the 4 metre rise

Looking at the shape of the storm surge

we examined what a 5 metre ocean rise might mean

and we are looking at

about a 10,000 square kilometre loss of land

with about 2.2 million people displaced

…

Finally understanding

that the news is neither good nor bad

it is simply that great differences are upon us

that great changes are upon us as a culture

and great changes are upon all planetary life systems

and the news is about how we meet these changes

and are transformed by them or in turn transform them

Salma Arastu

about the writer

Salma Arastu

As a woman, artist, and mother, I work to create harmony by expressing the universality of humanity through paintings, sculpture, calligraphy and poetry. Inspired by the imagery, sculpture and writings of my Indian heritage and Islamic spirituality, I use my artistic voice to break down the barriers that divide to foster peace and understanding.

I met Newton in March 2021 through my friend Heidi Hardin who was a student of Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison at UC San Diego in the early 70s. I was working on my project ‘Our Earth: Embracing All Communities’ which was inspired by the ecological verses from Quran. I published the book and Heidi Hardin arranged a Zoom meeting presentation about my book and invited pioneer Eco Artist Newton Harrison. I felt honored and was very grateful to learn that he has agreed to attend the Zoom meeting! I thanked Heidi Hardin for this great opportunity to join in conversation with Newton Harrison in this important talk “Women and Web of Life“.

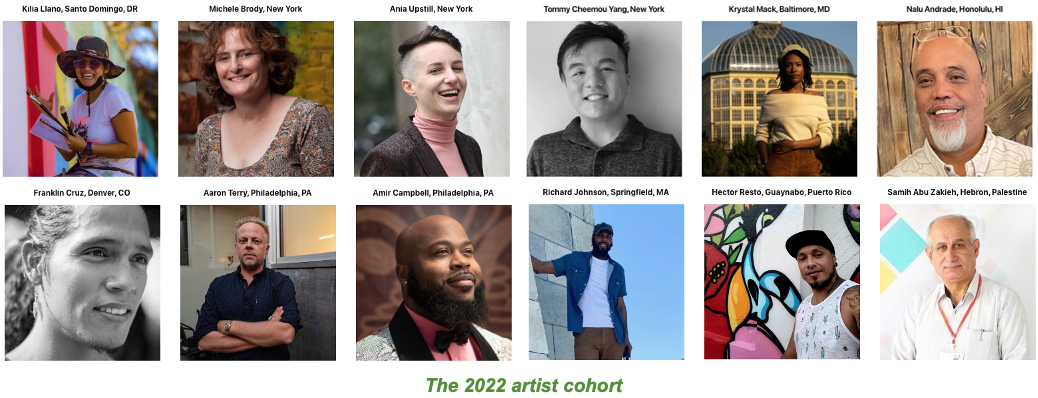

After that first introduction and hearing his encouraging comments, I emailed him my thanks and mailed a copy of my book too. He replied “Very interesting talking with you. I think you have an opportunity to engage your whole country using the Quran’s environmental positions to support your own or what you discover.” He shared his work, and we continued our communications through emails. He kept encouraging me by saying Female empathy and compassion must advance to save all life on Earth. He related an inspiring story of Helen’s compassion and dedication. He offered me to participate in the exhibition Eco-art Work: 11 Artists from 8 Countries at Various Small Fires in Los Angeles which was a great honor for me. I was given another honor to attend his surprise 89th birthday party on November 20th, 2021 with his close friends and that day I told him that I would like to visit him and meet in person. After that, he tried to schedule the time for my visit on March 24th, 2022 and, unfortunately, the cancer diagnosis happened, and the situation changed. I treasure his last email dated 5/17 when he sent me the image of his last work with these words:

“Thanks for your concern and good wishes. My treatments for the cancer have slowed me down. They are radioactive with added chemo. The course of treatment should end in about 2 1/2 weeks, and about 2 weeks after that I might be civil. Don’t want to lose contact. Very much hope things work out with your work and our gallery. Give me a call in about a month and I’ll see if I can’t make an afternoon with you. I am attaching a draft of my most recent work where I briefly become the voice of the Lifeweb, perhaps channeling in such a way that some of the stuff that I said surprised me after the fact.”

All the best, warm regards,

Newton

I hear his voice when I read Channeling the Lifeweb again and again. The words echo in my mind every day and night. My work after our meeting in March 2021 is totally impacted by his teaching. I have followed all projects executed by Helen and Newton Harrison, in particular through their book The Time of the Force Majeure.

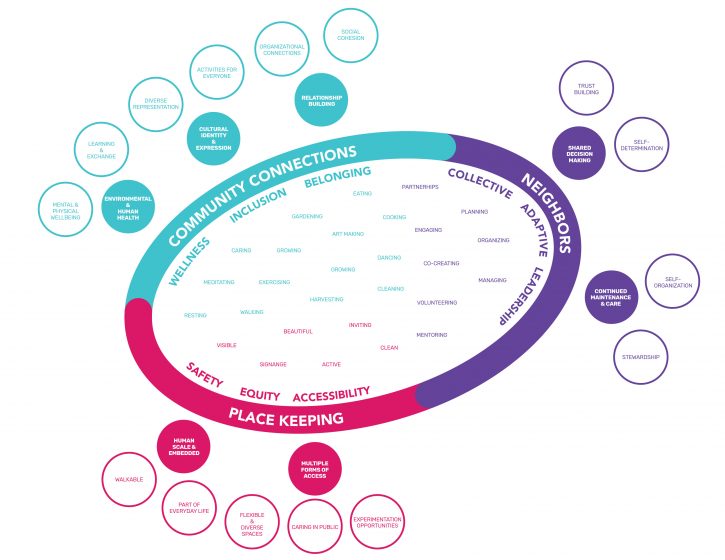

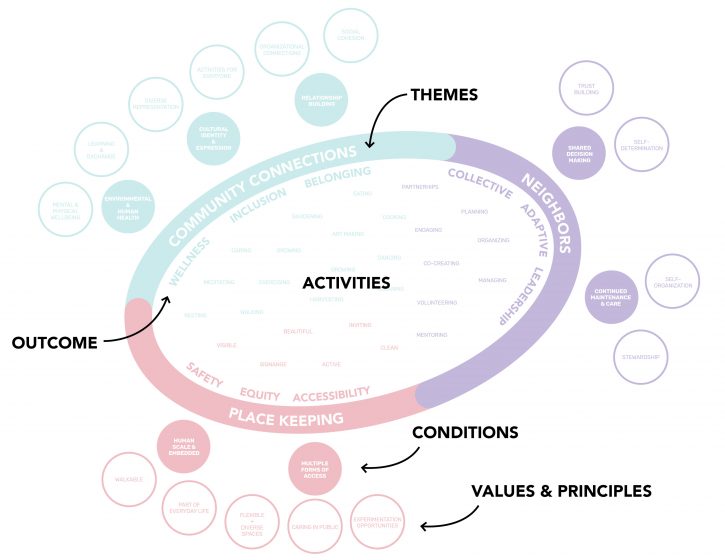

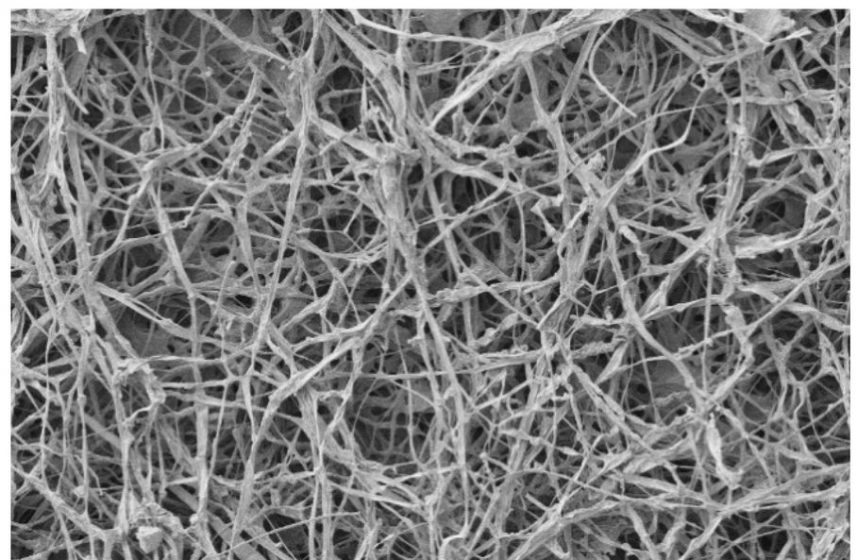

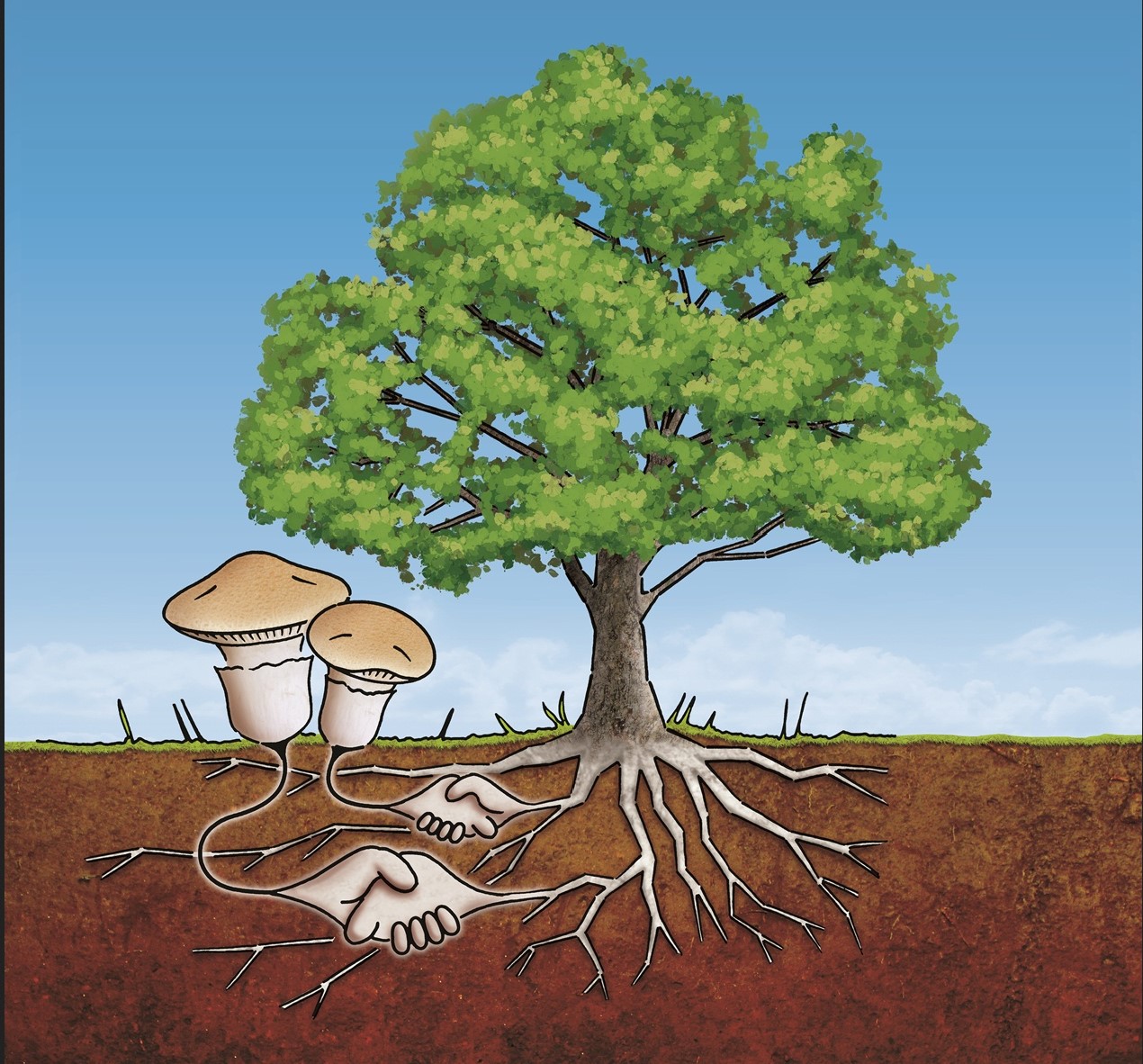

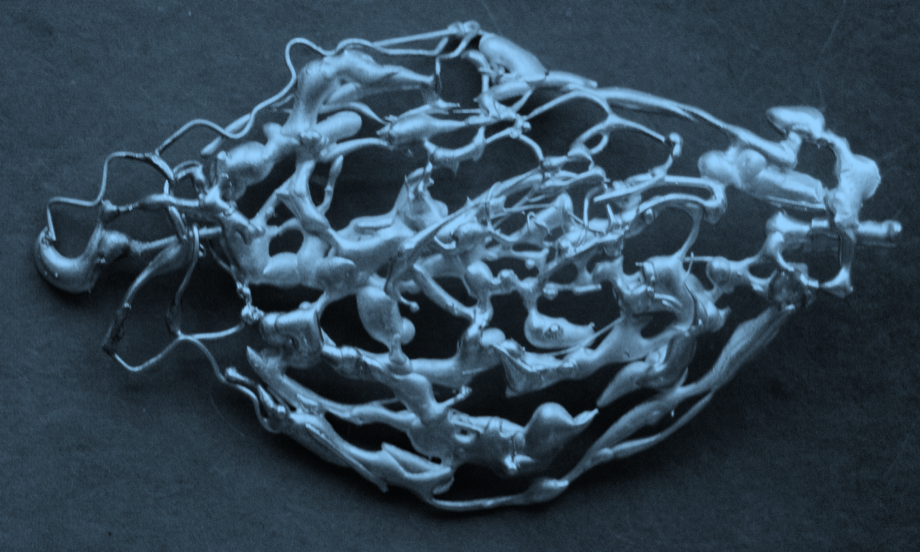

I have found myself immersed in research to gain deeper knowledge in science and faith to find remedies to save our planet and its ecosystems. I have found underground network of mycelia that is regenerating, activating, and healing the damaged state of our environment and invisible tiny benefactors Microbes who are an integral and essential part of the web of life. Bridging Science and Faith creates a visual discourse that bridges science, religion, Islamic diversity and diaspora, language engaged with the plight of humanity, the soul, and the soil. Now my artworks juxtapose the ecological phenomena of interconnectedness through mycelial flow with concepts from the Quran as expressed through Arabic calligraphy and Islamic patterns. The new series mirror contemporary issues with possible solutions based on science and spirituality expressed through moving lyrical lines.

Brandon Ballengée

about the writer

Brandon Ballengée

Brandon Ballengée (American, born 1974) is a visual artist, biologist, and environmental educator based in Louisiana. Ballengée creates transdisciplinary artworks inspired from his ecological field and laboratory research. Since 1996, a central investigation focus has been the occurrence of developmental deformities and population declines among amphibians and other ectothermic vertebrates.

Helen and Newton inspired me to open my mind to the possibilities of art moving beyond objects and ideas toward concrete actions that benefit communities ― ecological, biological, and social, and that connection of their special way of viewing challenges with systems thinking.

They also encouraged me for decades to continue, to go deeper into the research and ask the question ‘how big is here?’, then to follow fearlessly what I discovered. Along these lines, Newton encouraged the creation of Atelier de la Nature. Here in 2017, my wife, children, and I purchased heavily farmed land in rural Louisiana. Since this time, we have worked to regenerate the ecosystems from soybean and cane sugar fields into a nature reserve and eco-campus.

As a component of the restoration, Newton along with soil scientist Dr. Anna Paltseva have started a living artwork called Memory in the Life of a Cajun Prairie with the planting of 2.5 acres of native Louisiana “Cajun Prairie”. This type of prairie ecosystem is found nowhere else in the world and is considered an “endangered” habitat with less than 150 intact acres remaining today.

Memory in the Life of a Cajun Prairie is a living artwork that poses three questions. Is Cajun Prairie an effective means of sequestering carbon? As recent studies have shown prairie grasses work better than trees to sequester and store carbon in the soil. How do different types of disturbances affect biodiversity? There is a body of evidence that grazing and annual burning may change species interaction and diversity. Through this kind of collaborative art and science project, can we increase awareness? Can we inspire larger-scale Cajun Prairie habitat restoration?

Memory in the Life of a Cajun Prairie came about through discussions between Newton and me, and our desire to work together on something at the Atelier de la Nature. Between 2017 and 2021, the soil for Memory in the Life of a Cajun Prairie began to be worked by rebuilding topsoil and removal of nonnative species. In February 2022, we seeded over a dozen native prairie plants and took soil samples to record pre-prairie carbon levels. Over the next nine years, the plots of Memory in the Life of a Cajun Prairie will be experimented with by reseeding, carrying out various disturbances to monitor species diversity, and recording the effectivity of carbon sequestering.

Helen and Newton’s ideas will continue to bloom through Memory in the Life of a Cajun Prairie as well as in all of us they inspired so much.

Ruby Barnett

about the writer

Ruby Barnett

Ruby (Ruthanna) Barnett, Studio Manager and Senior Researcher at the Harrison Studio and Center for the Study of the Force Majeure from 2017-2021. After earning her Ph.D. in Linguistics, she provided advocacy in housing and homelessness, debt, employment, and welfare. As a lawyer in Oxford, she specialized in immigration and human rights.

The Harrisons – Greater than the Sum of their Parts

I worked with Newton from 2017 until 2021. In those first months, Helen visited the studio daily and I had the privilege of witnessing their deep love and tenderness. I traveled extensively with Newton and there is an inescapable intimacy accompanying a person in their 80s on long-distance travel. I prepared slides for talks, checked on his insulin supplies, laundered his clothes, drafted abstracts for conference proposals, and made sure his nose was moisturized.

Spending time immersed in the works of the Harrisons, as well as being part of the development of new works, has affected me deeply. My perception is forever changed. Newton liked to use Cezanne‘s Mont Sainte-Victoire series to speak on perspective but, for me, the work of the Harrisons caused a shift that has enabled me to embrace complex systems in a more visceral, thorough way than in my previous work. The form and non-form; the category of both-and; creating momentum, energy, from the oscillation between polarities. Understanding humanity as only one small part of the web of life, while at the same time comprehending the value of my own self-realization as an individual. The difficult and the charming. The tolerance and impatience. The compelling use of beautiful metaphor (“every place is the story of its own becoming”) contrasts with stark truths (“a tree farm is not a forest and tree farm floor is not a forest floor”). The duality is often shown as a conversation between elements—sometimes Newton and Helen themselves (Serpentine Lattice, Greenhouse Britain) or between others (the Lagoon Maker and the Witness in The Lagoon Cycle, the male and female voices in the Sacramento Meditations).

Inspiration for these arose from Helen and Newton’s ‘morning conversations’, developed after reading the Morning Notes of Adelbert Ames Jr., a scientist whose work was in vision and later in perception, developed a practice of setting a problem in his mind before bed, allowing his unconscious mind to work on it overnight and finding often that a solution had come to mind by morning. Helen and Newton experimented with this, conversing over coffee each morning to further elaborate ideas. In the later works, after Helen’s passing, Newton sought to call in her thinking, her voice, since they had actively worked to “teach each other to be each other” in the years prior, knowing that one may eventually be required to carry on the work alone.

The Harrisons knew that we can interfere, manage, or guide the life web only in limited aspects and that there may be unintended consequences. At the same time, choosing to take on the work, the only work of value in our urgent times, is balanced by knowing that all work addressing the continuing of the life web will by its nature be ennobling. It will change, benefit, and grow the one seeking to act. Helen and Newton’s fearless approach allowed them to face the stark reality of our likely future, and to plan pre-emptively, accepting some outcomes as inevitable. They maintained deep love, delight, and playfulness enabling them to model their vision and invite us to learn to “dance with the rising waters”. Helen and Newton’s lives and works embodied the whole being greater and other than the sum of its parts.

Barbara Benish

about the writer

Barbara Benish

Barbara Benish is a California-born artist, who moved from Los Angeles to Prague in 1992 as a Fulbright scholar. She founded ArtMill (est.2004) in rural Bohemia, an international eco-art center. From 2010-2015 she served as Advisor for U.N.E.P. in Arts & Outreach, and since 2015 is a Fellow at the Social Practice Arts Research Center, (University of California, Santa Cruz).

Helen and Newton arrived at the University of California, Santa Cruz, in 2009, the same time I did. When the mandatory faculty luncheon serendipitously had us seated next to one another on that warm fall day, overlooking the Monterey Bay, I felt elated to re-meet the pioneers of environmental art, surprised to find them in Northern California. It was an auspicious meeting, as I started a six-month Artist-in-Residence and teaching position at UCSC. We would become friends during that period, sharing Czech meals, (after learning of Helen’s Czech roots), but mainly talking about plants, rivers, maps, and things of the earth and sea. The Harrison’s were always willing to come to speak in my classes, generous with their time, and anxious to connect to the younger generation who would inherit the earth. They were natural teachers, both in and out of the classroom.

Their understanding of the consequences of ‘framing’, of giving humans a vision of the earth’s crisis in a way that is not catastrophic but regenerative, was the Harrison’s gift to us. Keenly aware of the connections of western capitalistic extraction, loss of natural resources, and culture, they kept the dialogue poetic and not didactic. During the times of Newton’s occasional amnesia towards female autonomy or ‘otherness’ in the room, Helen would gently, or forcefully, pull him back in. They were not a duet, but created a symphony between them, with their deep love and understanding of the natural world that was contagious.

Newton came to Prague at the invitation of our organization, ArtDialog, to lecture to several rapt audiences in 2019. We’d shown the Harrison’s work at our space, ArtMill in the Czech Republic, taught it in my lectures at the University, and skyped him in for Q and A’s over the years. He connected with my eldest daughter, Gabriela, who is now running our NGO, and listened to him talk since she was 13 years old. Over the past two years, ArtMill has been hoping to expand the Future Gardens project for Central Europe, working closely with Josh Harrison and the Center for the Force Majeure. Fittingly, the next generation will realize that dream.

The last visit with Newton, was on his porch in Santa Cruz, California, not far from our home here. It was summer and we were discussing our upcoming show at VSF in Los Angeles which he was curating. He would show his ‘obituary’ piece, an image of which he printed out on his xerox machine to show anyone stopping in. He knew he was dying, and yet still liked a good joke. When he called me to come over on the phone, he said “and bring me some of your cheesecake” (a forbidden treat due to his diabetes). When we talked about the plans for Future Gardens of Central Europe, which he originally wanted to name after Helen (Helenovice, “Helen’s Village”), home of her ancestors, he raised his hand for me to be quiet. “I’ll consult with the Life Web” …. and he closed his eyes. We were silent for many minutes, and it seemed the yarrow in the front yard was breathing with us. “Yes,” he smiled when he opened his twinkling eyes, “it will be good”.

Lewis Biggs

about the writer

Lewis Biggs

Lewis Biggs is Distinguished Professor of Public Art at Shanghai University (since 2011), and an independent curator (Artranspennine 1998; Aichi Triennale 2013; Folkestone Triennial 2014, 2017, 2021; Land Art Mongolia 2018). He is also Chairman of the Institute for Public Art, a global network of researchers concerned with place creation through culture / art-led urbanism, and supporting the International Award for Public Art.

I first became aware of ‘the Harrisons’ as a result of the controversy sparked by their contribution commissioned for the exhibition 11 Los Angeles Artists at the Hayward Gallery, London in 1971. Chiefly I recall a curator for whom I had great respect remarking that the artists were ‘charlatans’, which struck me forcibly. Had I paid insufficient attention to my own (still very youthful) enthusiasms for art in deciding which people involved were charlatans and which were not? Where is the line between shaman and charlatan? What is the role of authenticity in art? Is acting an art form? Portable Fish Farm: Survival Piece #III elicited many reactions that were more extreme than ‘charlatan’, and so contributed to the considerable expansion of the frame of reference for art in the following 20 years.

So, when Robert Hopper, with whom I was curating Artranspennine98, suggested in 1996 that we commission Helen Mayer and Newton to contribute to our exhibition, I was delighted to agree. The exhibition invited its audience to travel across the North of England from coast to coast (Hull to Liverpool or vice versa) experiencing around 40 mainly newly commissioned / site-specific artworks or exhibitions in 30 different locations. It was an invitation to artists and audiences to engage with the history and geography of the birthplace of the industrial revolution, the place where the modern understanding and appreciation of ‘landscape’ was invented.

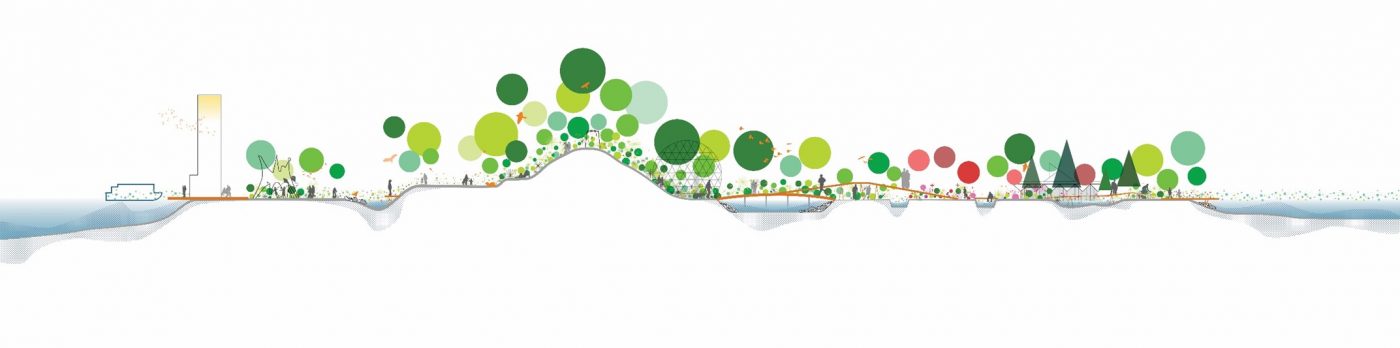

Helen Mayer and Newton were accommodated at Bluecoat Gallery Liverpool, where Bryan Biggs (no relation) the Director was a very welcoming collaborator and host. They were invited to collaborate with local people to explore the possibilities for regeneration in the area and to exhibit the resulting maps at the Bluecoat and on the internet. They proposed that all the rivers should be cleaned, and woods and meadows expanded. That the geological timescale of re-establishing flora and fauna to ‘health’ could be speeded up through better use of existing ‘wastes’ and spoil heaps. The project was titled Casting a Green Net: Can It Be We Are Seeing A Dragon? The image they found in the coast-to-coast map of the country showed the body of the dragon through the industrialised lower ground and valleys, the wings of the dragon in the Pennine hills.

I’m not sure what or whether they contributed to a shift toward social consciousness about the environment. I remember being impressed with how the artists would pounce on specific words that emerged in the public workshops and highlight them for further discussion. A process of simplification presumably resulting from their many years of practice with workshops and focus groups. Bryan remembers how they constantly bickered with each other, and I remember thinking that their approach was aggressively ‘direct’ in that un-English way. But we were all impressed with the quality of the research that went into the production of the various maps, and how very thought-provoking their synthetic approach (art-science-text-image) could be. That for me is their significant legacy, plus the fact that they were gifted communicators: I think of their Rorschach process to ‘discover’ iconic images from maps every time I’m faced by an artist who struggles to find an image or a metaphor that expresses their project.

Tim Collins

about the writer

Tim Collins

The Collins + Goto Studio is known for long-term projects that involve socially engaged environmental art-led research and practices; with additional focus on empathic relationships with more-than-human others. Methods include deep mapping and deep dialogue.

Art and Change: The emerging social and ecological impetus

A Dialogue from 2000 – with some edits and approval to publish from 2023.

Original Authors:

Jackie Brookner, Parsons School of Design, New York

Tim Collins and Reiko Goto STUDIO for Creative Inquiry, Carnegie Mellon University

Newton Harrison, and Helen Mayer Harrison Emeriti, University of California, San Diego

Ruth Wallen, Artist and biologist, San Diego

Josh Harrison, Director, Center for the Study of the Force Majeure, UC Santa Cruz

In 2000, we were engaged with the Harrison’s traveling to their home in San Diego with some regularity. Everyone involved in this discussion was struggling with adjunct, temporary, and year-to-year academic contracts. The Harrison’s proposed a dialogue which we might use to shape our individual and collective futures.

Art and Change Pedagogy

Philosophy: Nature as model, as measure, as mentor

Foundation Concept: Symbiosis and the biological imperative

Program: Ecologically engaged, Politically engaged, Socially engaged.

Emerging Issues: The public realm (social and natural) is in need of interventionist care. The visual arts with a history of value based creative-cultural inquiry are best equipped to take on this role. The long term goal, is to develop a cultural discourse which will:

1. expand the social and aesthetic interest in public space to the entire citizen body,

2. re-awaken the skills and belief in qualitative analysis (versus professional-quantitative analysis), and

3. preach, teach, and disseminate the notion that everyone is an artist.

The Problems: Artists are unprepared to take a productive role in civic discourse. Students graduate without the tools and bridging experience to allow them to learn the languages and process in the areas of ecology, politics, and sociology, and are therefore unable to enter into effective creative communication.

While information technologies is a burgeoning area of technical expertise, theory, and expression in the university setting, the emerging biological revolution is all but abandoned to the sciences. There isn’t a single department in the country with a program area which addresses the changing meaning of nature, restoration ecology, and bio-technology.

The traditional subject matter of art as well as the teaching methods taught in US art schools need an additional layering of information and training to expand the efficacy of an artists voice into these complex realms. Artists have always critiqued and revealed belief systems, the program will teach artists to be effective agents of change. We seek to define the pedagogy of engagement.

An Eco-Cultural Engaged Art: We propose a rigorous program of engagement training, providing artists with the theoretical and practical skills allowing them to productively engage the civic realms of politics and society with a primary focus on ecology/biology. In affect, we seek to transfer the language and skills which will allow artists to engage their colleagues in the professions of planning, design, and policy with equity and efficacy. Furthermore, to meet the challenges of a public realm increasingly challenged by private interests and legacy impact, the position of the artist will be defined in relationship to civic discourse rather than primary authorship.

The proposal includes a Graduate Major structure, an Undergraduate Minor/Concentration and a University Level Interdepartmental Credit Foundation Course. This was classic Newton, as he thought through the economics and the progression of creative/intellectual development which would be necessary for this new course of study. We can ‘hear’ both Helen and Newton’s voices throughout this proposal. We can also feel the love and care they put into this.

Janeil Engelstad

about the writer

Janeil Engelstad

Janeil Engelstad is the Managing Director of the Global Innovation and Design Lab and an Embedded Artist and Lecturer at University of Washington, Tacoma. The Founding Director of Make Art with Purpose, Engelstad produces Social Practice projects that address social and environmental concerns around the world.

Helen and Newton Harrison: Re-imagining the Context of Art

The following text recounts one of many experiences I had with Newton and Helen Harrison, as well as a sketch of their creative process. The Japanese term, kenzoku, which literally means family and the presence of the deepest connection, expresses our relationship and exchange.

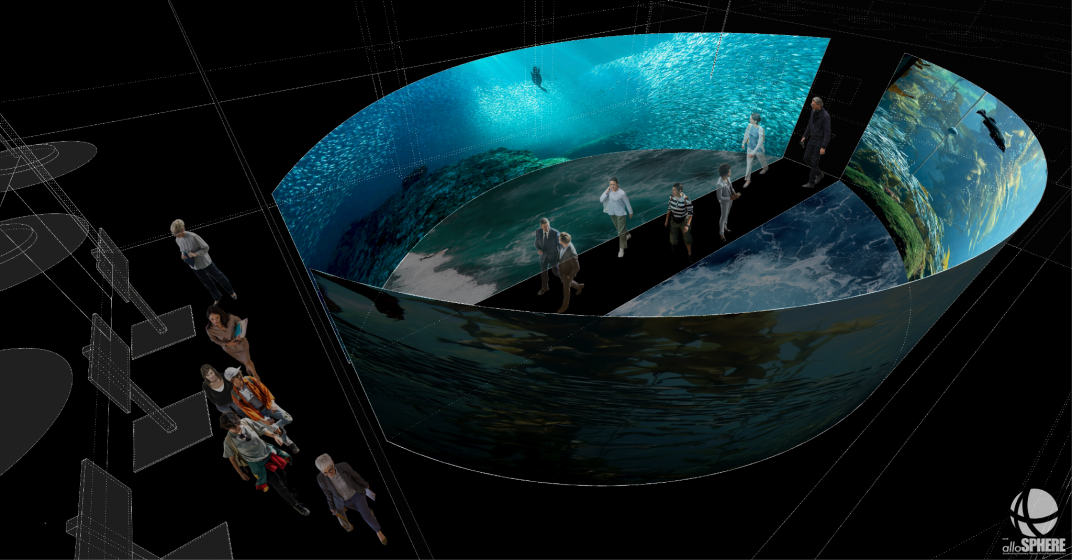

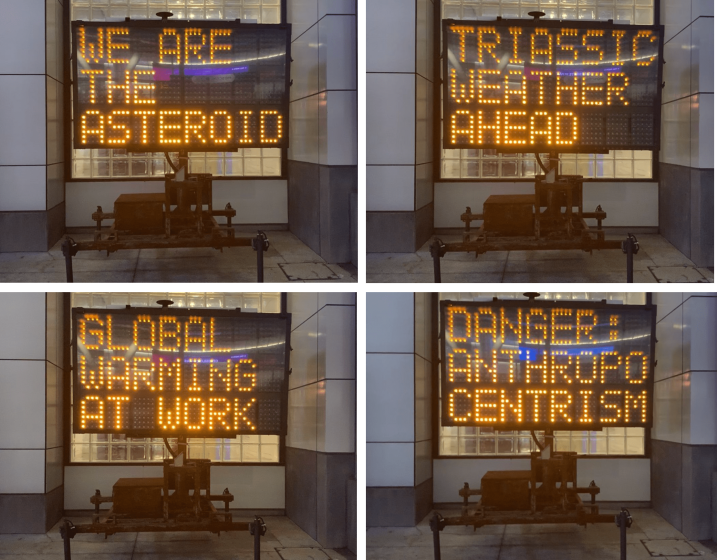

In October 2016, Newton Harrison came to Seattle to participate in 9e2 Seattle (9e2), a festival that marked the 50th anniversary of 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering (9 Evenings). Produced by Robert Rauschenberg and Billy Klüver, the original 9 Evenings was the first of several art and technology projects that would evolve into the non-profit group Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.). 9 evenings consisted of hybrid art performances and video, created by ten recognized artists working with some 30 engineers from Bell Labs performed at the New York City 69th Regiment Armory, from October 13 – 23, 1966. The performances were as much about the new technologies the artists employed to realize their work as the themes being explored.i In contrast, 9e2 examined contemporary themes impacting the way people experience life on Earth, such as climate change, AI, and social justice.

Conceived and produced by Seattle writer and cultural producer John Boylan, 9e2 was organized by a curatorial team from the arts and technology fields. Boylan’s purpose was three-fold: to teach and inform (the history of 9 Evenings was little known among the local tech and creative communities); to build connections between local, national, and international artists and technologists; and to explore ideas about how artists, technologists, and other creatives function in the world. “Underpinning this purpose,” Boylan recalled “were the questions: What are you doing? Why are doing it? How are you doing it and, to an extent, what does new art mean?”ii

As a member of the 9e2 curatorial team, I organized a handful of projects and programs, including a conversation with Newton. He was thrilled to participate, for this was an occasion for him to publicly reflect on his conversations with Billy Klüver around the time that E.A.T. was being organized.iii “He had it all wrong,” Newton recounted, “and I told him thus: artists and engineers should not be focused on creative experiments exploring the impact of technology on the individual and society. Rather they should focus on how technology can be of service to ecology and the planet.”iv The growing impact of climate change, Newton believed, had proved the relevance of the environmentally focused work he had produced with his wife and creative partner, Helen Mayer Harrison and the misdirection of Klüver’s focus.v Additionally, Newton appreciated that the larger purpose of 9e2 connected to the Harrisons’ inquiry into the meaning of art and art making in the latter half of the 20th century, as the impact of commerce, industry, and development on the Earth’s eco-systems were becoming more and more evident.

Throughout their careers, Helen and Newton cultivated a wide creative and scientific community and I would wager that almost everyone in this community could tell dozens of anecdotes like the one I shared about 9e2. Long-time academics, Helen and Newton naturally imparted their experiences, ideas, and wisdom through storytelling and conversation. They were also skilled at asking questions that moved and transformed ideas and thinking into deeper reflection and expanded consciousness.

At the forefront of environmental art and interdisciplinary, collaborative design and production, the Harrisons imagined and were utilizing design thinking before companies like Ideo and Stanford’s d.school brought the process into the mainstream. Making Earth, Then Making Strawberry Jam (1969-1970) begins with Newton’s growing ecological awareness and empathy for earth. Through his research, Newton learned that “the topsoil was in danger in many places in the world. So, I took the decision to make earth . . .,” he wrote about the project.vi

The Harrisons would invest months and sometimes years in the empathy phase of their projects. Researching and meeting with people who had expertise in the history, ecology, and politics of the place and/or problem that a project might address. They sought information and expertise from noted professionals, as well as people on the edges of mainstream thinking and from Indigenous people before it was politically correct to do so. Practicing deep listening, they had conversations with the Earth itself. Then, they would define problems in poetic texts that framed their initial research into inquiries, conversations, wonderings, and proposals, which they sometimes called think pieces, such as Tibet is the High Ground:

Thinking about the greening of Tibet approximately 772,000 square miles

Which is eighty percent of the 965,255-square-mile Tibetan Plateau

We imagined a domain that was about eighty percent savannah

And twenty percent open canopy forestFor a productive, self-sustaining & complicating landscape to develop

Bold experimentation becomes an absolute requirement

For instance with glaciers retreating

We imagined assisting the migration not so much of species

But of species ensembles that form the basis

For a succession ecosystem to form

That follows glaciers uphill

We then imagined a water-holding landscape

Where terrain was appropriate

And subtly terraformed so that rains

Stayed on the lands on which they fellIn order to locate species groupings

that would form the basis for generating

a uniquely functional future landscape

Where harvesting preserved the systemsAlso, drawing botanical information from the recent Pliocene

When the weather was the same

As that predicated in the near future

Taking on the problem of inventing an edible landscape

Which will be self-seeding and perennial

A landscape unique in its food-producing qualities

As the harvest preserves the system

And this kind of designing as endlessly repeatable

A green plateau can sequester 3 gigatons of carbon a decadeTibet is the High Ground, 2005vii

Rich with ideas, metaphors and instructions, Helen and Newton’s texts offer tutelage in communion; setting out on a course of action; prototyping, testing, then putting into place projects around the world; a handful that will continue well into this century.

At the center of their work was love and perhaps this is the greatest legacy that the Harrisons leave. Love of life, love of each other, love of people, and love of the planet. This value fueled courage and gave them the freedom to let go, experiment, and knowingly create work that would come to fruition after they passed. This letting go of ego, creating work where Earth was the client, was critical for the Harrisons and should be for all of us who wish to advance solutions that lessen the impacts of climate change and improve life for humanity and the planet.

* * *

i While a few performances, such as Robert Rauschenberg’s Open Score, were an indirect commentary on contemporary issues such as the Vietnam War, Klüver did not position his curatorial work on the impact of technology on society until the organization of E.A.T. About 9 Evenings he wrote: “It is important to realize (understand) that 9 Evenings was a realistic event. It wanted to achieve very specific practical and social goals. Its development was coincident in time with the spreading mysticism about technology, the McLuhan concept that the communication means were extensions of the body, the psychedelic experience as an element of art! 9 Evenings was none of that. (The artists and the engineers) were rigorous, energetic, and authoritarian and would demand completely controlled situations. That the forces behind 9 Evenings should have converged at that time, must have been separate from political developments of the global art, psychedelic kind of situation.” (foundationlanglois.org)

ii J. Boylan, personal communication, February 2023.

iii One of E.A.T.’s first activities was to organize loose, international groups of artists and engineers, by geography, to potentially collaborate with each other. Newton was an early member of the United States’ West Coast group.

iv N. Harrison, personal and public communication, October 2016.

v N. Harrison, personal and public communication, October 2016.

vi Harrison, Helen Mayer & Harrison, Newton. (2016). The Time of the Force Majeure. Munich, Germany: Prestal

vii Center for the Study of the Force Majeure. (2018). The Center for the Study of the Force Majeure. [Pamphlet]. Center for the Study of the Force Majeure.

Les Firbank

about the writer

Les Firbank

Les Firbank is a British ecologist specialising in the sustainable management of land, with a particular focus on European agriculture. He collaborated with the Harrison while working at the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and then at North Wake Research, both in England. He has recently retired from his chair in sustainable agriculture at the University of Leeds, and is a member of the European Food Safety Authority panel on genetically modified organisms.

For me, it was about the process and not the product, it was about the collaboration and not the outcome. I’m a professional ecologist (now retired) and first came across Helen and Newton when one of their helpers phoned me up one Friday afternoon to ask for access to some landscape data I had access to. If I had been busier, or if it had been another time of the week, I would have pointed her to our website and left it that. But I was intrigued, Why did you want them? She didn’t know but would get the project leader to call back. Newton called from Manchester and explained they were mapping the north of England. Quite why a Californian artist duo wanted to map England from a base in Manchester baffled me, so I went down to meet them and their team. They were working on the ArtTranspennine98 piece entitled Casting a Green Net: Can it be we are seeing a Dragon? piece, re-imagining the area between Liverpool and Hull. The eventual outcome was a series of hand-coloured large-scale maps of the region. Each showed a different aspect of the area, one with planned housing developments, one with nature areas, and so on. I wasn’t too impressed until I went to the exhibit, and watched people react to the work. They moved in closer and back out, walking from map to map, getting a sense of their area and what was nearby. It was like a GIS but required physical interaction and engagement. For me, the work was the fun. I met with people from the industry, regulators, and the arts, but unlike in most of my meetings, people were able to be open and honest about their thoughts, as it was ‘only’ an arts project. This allowed a level of communication not possible in more formal settings, where the participants have their ‘party lines’ to protect. Communities of practice were set up that persisted long after the project ended.

I worked with them again when I moved to Devon in 2007, where with David Haley we started a pilot project to design a sustainable village in the area. We set up a week-long workshop based in an agro-ecological research station in the region, enlisted an environmental GIS specialist Bruce Griffith, and set about our work. We made a good start to the work but, for various reasons, it did not really develop. The story can be found in a book chapter we wrote ‘A story of becoming: landscape creation through an art/science dynamic’ (Firbank, Harrison, Harrison, Haley, and Griffith. In Lobley and Winter (eds) 2009, What is land for? Taylor and Francis). Again, the pleasure was the discussions that addressed key questions which academics tended to shy away from, they were too broad. What do we mean by sustainability? How much carbon should one household have access to? Do we need livestock (yes!)? Was this really art? Before I had met the Harrisons I would have said no, this was ecology. But they taught me that anyone has the right to ask these questions and to seek and present answers, framed as they see fit. I framed my work in scientific papers, they used works of art. I used statistical tables; they used poetry and images. They are complementary, reaching different people.

Our art/science dynamic was based on mutual respect and talking through different approaches to common questions, rather than the more usual multidisciplinary approach of artists seeking to illustrate the science. Such questions have since become more widely asked, but tend to be answered too quickly, lacking in rigor. But I have tried to retain this questioning attitude and to pass it on to my students.

Cathy Fitzgerald

about the writer

Cathy Fitzgerald

Dr. Cathy Fitzgerald, Founder-Director of the global online HAUMEA ECOVERSITY. Empowering creative, cultural, and business professionals for wise, compassionate, and beautiful creativity. Consultant, international speaker, advisor, and mentor on ecoliteracy & accredited ESD transformative learning Earth Charter educator and Research Fellow on Art & Ecology for the Burren College of Art.

Helen and Newton Harrison’s work has powerfully influenced my thinking and creative practice since the late 90s. I still clearly remember the afternoon coming across a summary journal article about their work in the library of the National College of Art and Design in Dublin, Ireland. I recall feeling intense relief at finding a comprehensive articulation of the multi-constituent aspects of ecological art practice and over time it shone a light on a path for me to develop similar creative ecological endeavours. The Harrisons’ reflections on their dialogical, participatory, question-led practices helped me understand why integrated, more holistic practices are a radical departure from the conventions of modern art, and why they have the social power to inspire people to live well for place and planet. Today, largely inspired by the Harrisons’ practice over many decades, I would argue ecological insights must inform and guide creative practice—and all our activities—for personal, collective, planetary, and intergenerational well-being.

However, with little college or peer support, my progress to develop and articulate a similar practice to the Harrisons was very slow. Around the late 90s, I was also reading art critic Suzi Gablik’s Re-enchantment of Art and Conversations Before the End of Time. For many years afterwards, I was mystified why the Harrisons’ and Gablik’s work was rarely discussed in my undergraduate or postgraduate art studies, or even during doctoral research that I completed in 2018. Looking back, I believe I came to this topic earlier than most because I had previously worked in science and environmental advocacy. It also took me time to appreciate that illiteracy around ecological understanding, common in current art education, profoundly precludes many from understanding the gravity of humanity’s predicament, and correspondingly why ecological insights insist on a paradigm shift in contemporary art and the dominant culture as a whole.

My difficulties to develop an ecological art practice continued through my doctoral studies; I found it difficult to push past artistic conventions and disinterest that the ecological emergency was a crisis of the dominant culture. Even with my background in science, I had to persist to explain my audacity to explore creative practices that crossed disciplinary boundaries and lifeworld experience. Here the published journal articles on the validity and importance of the Harrisons’ pioneering prescient practice, with others following in similar ways, literally gave me permission to continue my practice and research. I will always be grateful, remembering a particularly difficult time around 2011 when I was considering abandoning my doctoral studies, when Helen and Newton wrote to me out of the blue ‘Dear Cathy, from our perspective, very good work!’

Today, I feel the relevance of the Harrisons’ work is stronger than ever. I can also confirm that the importance of their journey to develop and articulate ecological practice extends beyond the contemporary art world to contribute to envisioning best practices in broader sustainability education. These realisations arose recently after an unexpected opportunity to learn with leading international sustainability educators at Earth Charter International, which hosts the UNESCO Chair of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). Looking at their key research insights of emergent holistic education for sustainability —integrated approaches to advance wisdom on how we must live well with others and the wider Earth community— I realise that the Harrisons’ real-world ecological art practices, facilitating communities to creatively question and embrace many ways of knowing, exemplify developed participatory, multiconstituent ecopedagogy. Additionally, the Harrisons provide much insight to sustainability educators on how creative practices, in particular, are essential to make sustainability learning inclusive and inspiring to diverse communities. As our society and the art world becomes more ecoliterate, I believe the Harrisons’ (and similar creative-led ecological practices) leadership will be more appreciated. For me, this is the most profound legacy of the Harrisons’ work – understanding how creativity is an essential driver for holistic ecopedagogy across all education.

Johan Gielis

about the writer

Johan Gielis

Johan Gielis (1962-) is a Belgian mathematician-biologist, originally trained in horticultural engineering and landscaping. He has worked in plant biotechnology for over 25 years, with special focus on mass propagation and molecular and physiological aspects of tropical and temperate bamboos. In 1997 he discovered the Superformula, based on observations in bamboo.

A botanical Kepler and his Newton

My work, which has its origins in botany, shows that shapes as diverse as starfish, flowers, squares, and cacti, the shape of atomic nuclei, and even our universe itself can be encoded in a geometric transformation called Superformula. So far, we have studied over 40000 individual biological samples, all of which are described by the Superformula; interestingly we found no circles or straight lines, the basic tools of our sciences. Our methods have now become a complete scientific methodology, with surprising new insights into how nature works and speaks to us. The attraction of the Superformula may lie in humanity’s need for a unified and continuous approach to life, nature, and our universe, as opposed to the discrete, random nature of our scientific worldviews.

What matters is not the individual forms, but how they are connected. Newton’s specific question was whether this would also teach us about ecosystems and continuity (he did not think the term sustainability should be used). He challenged and inspired me to look more deeply and broadly at ecosystems and our planet. How can we use these insights to “reshape and redirect the suicidal and ecocidal direction in which our Western civilization has taken us,” as Newton put it.

This is the direction I am currently pursuing with my mathematical friends. It is indeed possible to describe complete systems. The heart, once thought to be a pump, turns out to be a simple helical structure. Furthermore, the entire circulatory system combines the functions of transport with those of exchange, switching between a cylinder (for transporting blood) and a Möbius strip, a one-sided body for exchanging oxygen in the lungs and cells. These models should also work for ecosystems, translating holistic views into precise mathematics, as a language for the sciences and, he hoped, for the web of life.

Like nature, science is a never-ending endeavour, and what is cutting-edge today will be fossilized in the not-too-distant future. The Superformula is seen by many as the linchpin in this evolution. Another realization is that mathematics in its current state is a poor substitute for our deep knowledge. Mathematics is known as the language of science, the science of patterns. It is bad because it fails, as I call it, in its task of describing both patterns and the individual. With the Superformula, we can now study both the general and the particular, and link the discrete and the continuous.

After the publication of my article in the American Journal of Botany, many were excited by the idea of a unified description of the large and the small. This happened earlier in the sciences when the work of Kepler and Galilei inspired Isaac Newton to develop his System of the World half a century later. The American Mathematical Society wrote: “A botanical Kepler waiting for his Newton.”

How fortuitous it then was when Newton H. contacted me. It was not the Newton who would develop an updated world system or theory of everything based on my work. Instead, I got the opportunity to know Newton Harrison, a great artist and human being. However brief, our communication left a deep impression and will continue to be an important inspiration for my work in the sciences.

Reiko Goto Collins

about the writer

Reiko Goto Collins

Goto employs an experimental practice of empathic exchange with people, places, and things. She earned her PhD in Ecology and Environmental Art in Public Places in 2012. Collins is driven by the pursuit of transformative experiences and ideas that can empower people, places and things. He received his PhD in Art, Ecology, and Planning in 2007.

Helen Harrison: Our normative cultural behaviour, and then you see if there is some way that you can reverse it. When people see the flip, and the reverse, they understand.

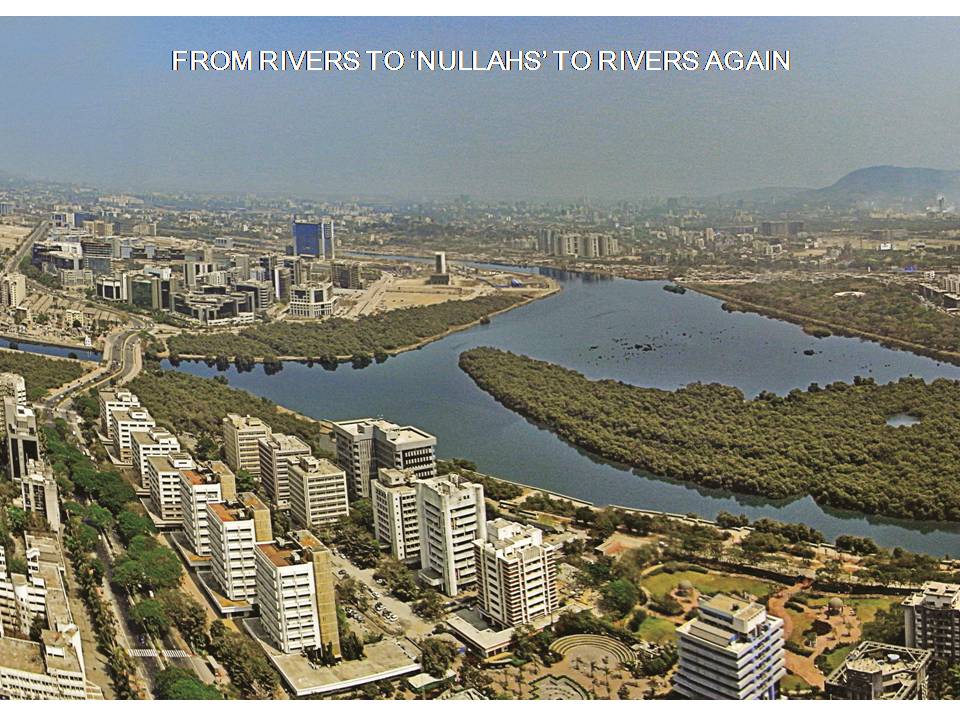

Newton Harrison: Let me give you an example. Flood control is a metaphor. Now, what is flood control? Flood control is defined by dams and dikes that hold the river, keep it from flooding and wrecking a town. But the dikes also destroy the river.

Helen Harrison: Flood control is also the destruction of flood plains. Flood plains are meant to be flooding.

Newton Harrison: And the destruction of river life – a lot of destruction in that metaphor. If you flip the metaphor, flood control is the spreading of waters – then you give me the twenty million dollars that you were going to put in the dikes; I will go and buy land above; and a whole load of design will happen which we call ecological design.

Helen Harrison: We will return the flood plain to the river. We will have removed …

Newton Harrison: Reiko is not understanding how one got to begin at the beginning again.

Reiko Goto: Hey, dikes are not metaphor – they are real structures!

(Goto Collins, 2012, p.70).

Through this conversation I have learned three things: 1) metaphor can be physical, 2) physical metaphor can be dysfunctional, and 3) a metaphorical flip informs how we understand a functional metaphor. A metaphorical flip’ is like ‘light and shadow’, ‘pull and resistance’, and ‘joy and sorrow’. It reveals or creates a dual reality.

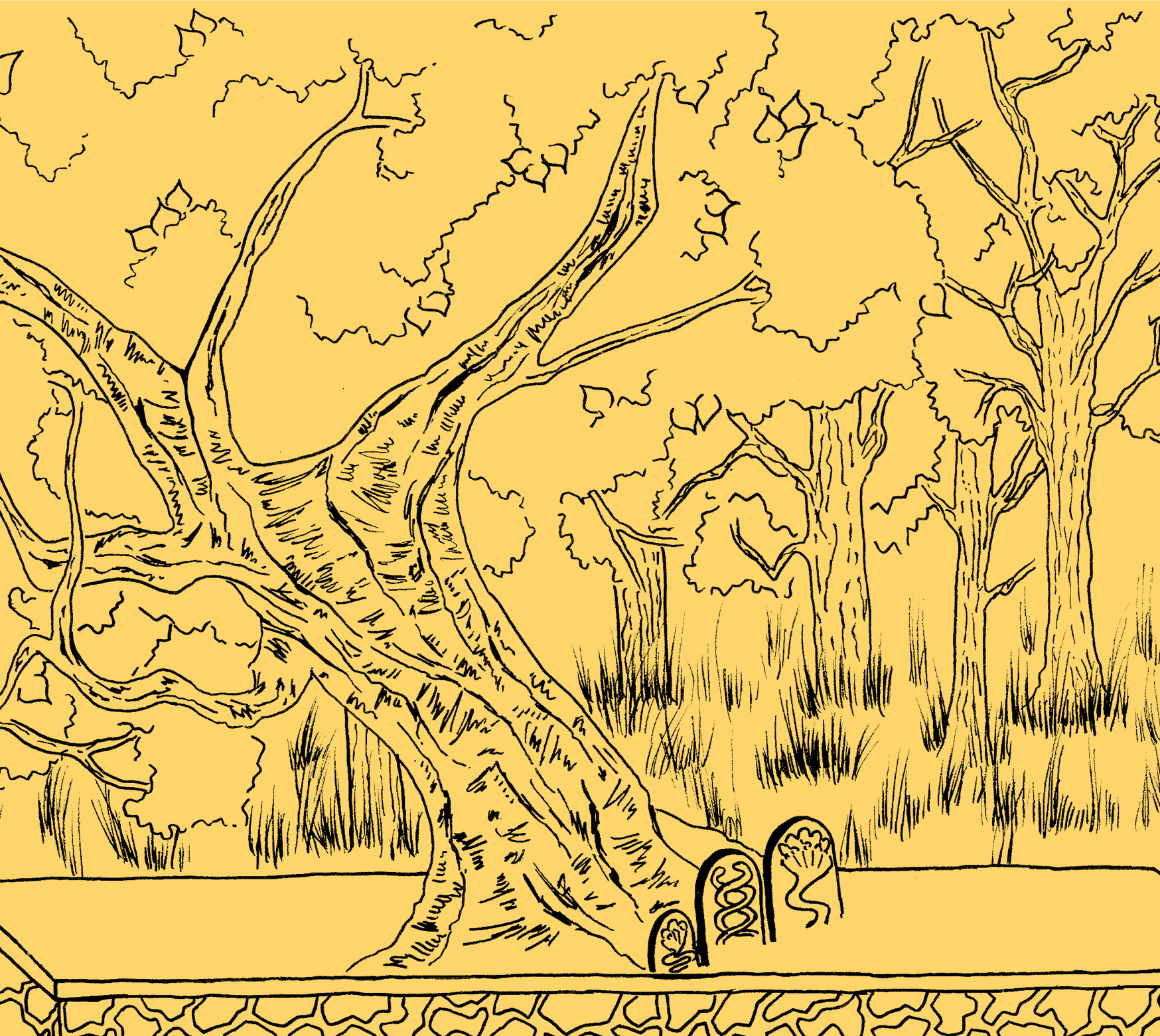

A dual reality is not imagination, it is also found in the natural environment. For example, Caledonian pine, known as Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris), grows differently in different environments. In forest plantations the competition makes them grow tall and straight.

In open areas, the branches spread out to catch more sunlight.

Both natural events and human actions affect the shape of the tree. The dual reality of the pine tree has two different values: straight-utilitarian value and curvilinear-aesthetic value. Understanding two different values of Caledonian pine can give us choices in how we relate with the tree.

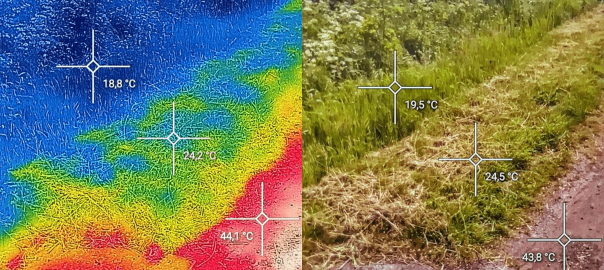

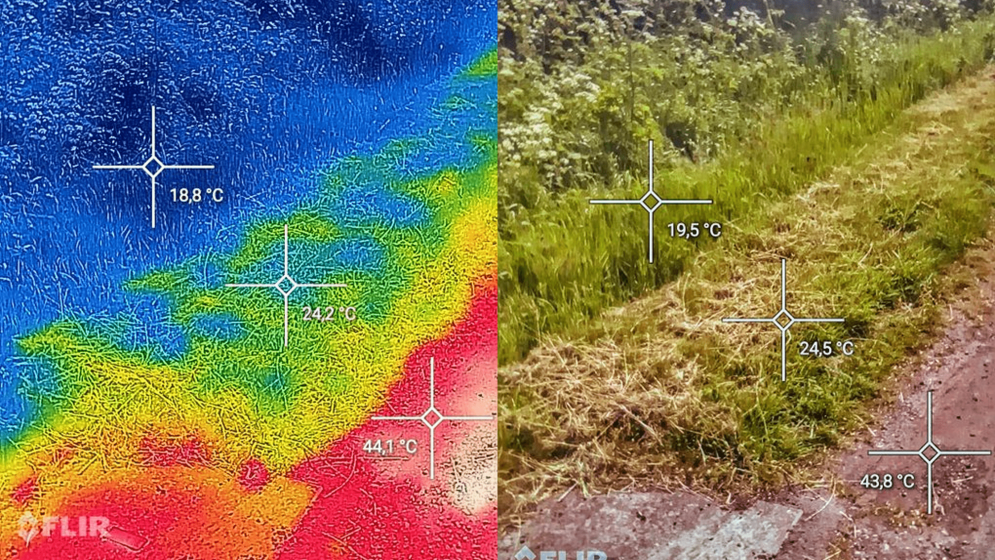

Image right: A Caledonian pine in Black Wood of Rannoch, Scotland. Digital image: Collins + Goto Studio, 2013.

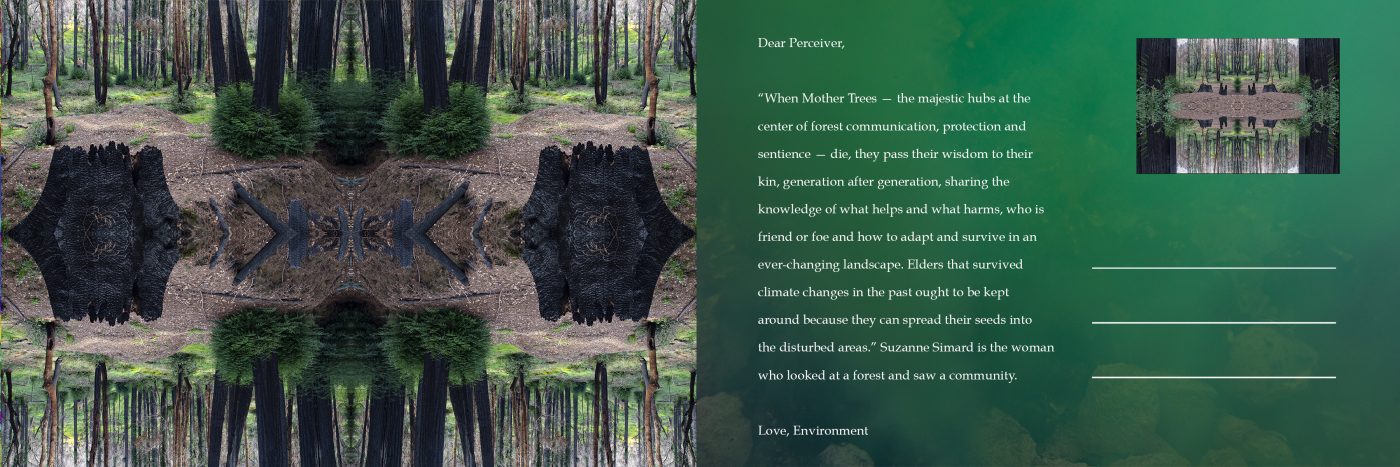

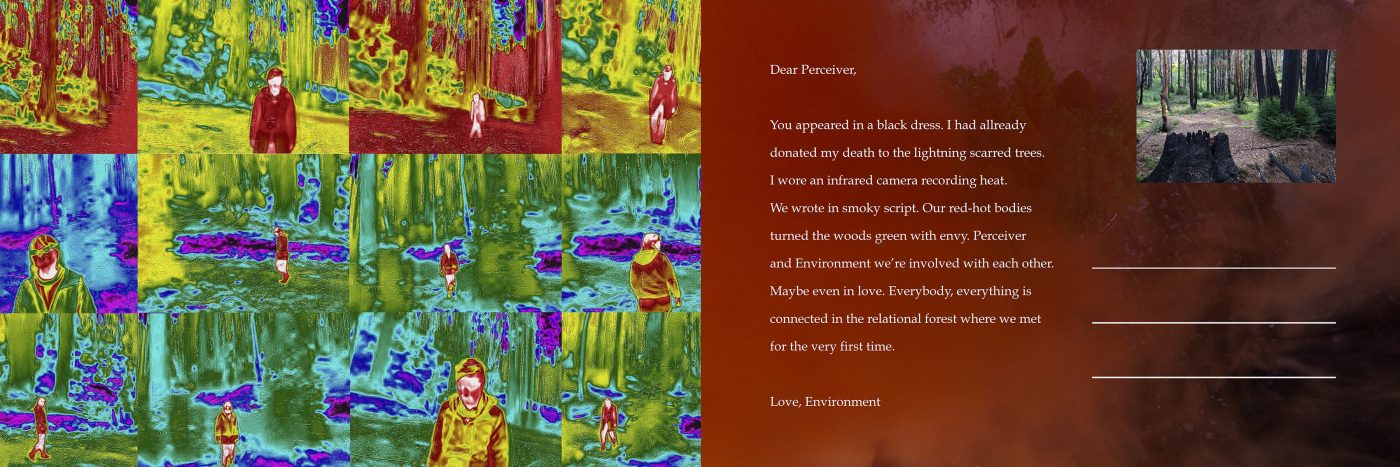

Terike Haapoja

about the writer

Terike Haapoja

Terike Haapoja is a visual artist based in New York. Haapoja’s work investigates the existential and political boundaries of our world, with a specific focus on issues arising from the anthropocentric world view of Western traditions. Animality, multispecies politics, cohabitation, time, loss, and repairing connections are recurring themes in Haapoja’s work.

Like many, I was introduced to Helen and Newton Harrison’s work in art school. In the early 2000s, when I studied, ecology wasn’t yet trending, and their work seemed like fresh air for someone like me who felt that the most urgent question in the world, the environmental crises, was surrounded by a numbing silence. My own work, however, was video-based and centered on the figure of the animal, and while our works sometimes ended in the same shows, we never met in person.

Then, on one dark evening in 2019, I saw a message request on Facebook, and when I clicked on it I found a message from the legendary Newton Harrison. He had encountered one of my works somewhere and wished to connect. I was delighted and honoured, and we started an exchange that evolved into emails and Zoom calls and lasted until his passing.

One of the first works he sent me was a meditation on sea ecologies called Apologia Mediterraneo. The ten-minute video combines found footage and Newton’s voice-over, reciting a poetic letter addressing the sea and the troubles and pains it has to endure. Newton’s voice radiates empathy and solidarity with the Mediterranean Sea, and this empathy towards and solidarity with the more-than-human world always characterised his attitude and our discussions. He would passionately side with the web of life in our conversations on environmental justice: he wanted to be responsible and accountable to it directly, not to a human political system that represented a species he called ”an ungovernable exotic” that always hoarded resources to ”the human reproductive machine”.

We discussed empathy and what awakens it in people. We agreed that it had to be an embodied, particular experience because one can not convince another to feel for an animal, or an earthworm, or earth itself by rational arguments. For Newton, this kind of awakening had happened early in life, when he was driving along a highway in California, seeing the broken landscapes under constant, violent human excavation. Suddenly, he said, he could hear the earth screaming. From then on, earth was someone, not something.

He talked about his career becoming huge at the age of 88. There was no sign of slowing down, on the contrary: he didn’t want to make compromises or to scale his ideas down, but for the world to change, and his work to become more than a representation of what life on earth could be. He wanted it to be the real thing. Helen’s Town, a homage to Helen in the form of an eco-village with a production timeline of hundreds of years (because that’s how long it takes for trees to grow) was a serious dream and his frustration with curators who instead wanted something gallery size was palpable.

In 2020, when the pandemic had locked all of us in, I invited him to contribute a dialogue with me to a small exhibition I made about art, love, and relationality. My premise was that as artists our practice is always impacted by the relations that carry us, and our muses, whether they are human or more-than-human. In our dialogue he talked about his lifelong work with Helen and their mutual excitement towards their work and life together, and how it was her who had initially led them to the question of climate change. And how everything that he did was and would be informed by her and their work together, and how her perspective still acts as a moral compass to Newton. Because, he said, ”Helen had the best ethical sense of anybody I ever met in my life, with one exception: Eleanor Roosevelt. So I put the bar high.”

I remain grateful for that Facebook message and that I had the honor of befriending this pioneering ecological thinker for these last years. In an email on the 10th of March, 2020, Newton wrote: “If possible I would love to democratize a little bit of hope in what

appears to be an ongoing and increasingly intense array of

catastrophes.”

We still have time to do just that.

David Haley

about the writer

David Haley

David makes art with ecology, to inquire and learn. He researches, publishes, and works internationally with ecosystems and their inhabitants, using images, poetic texts, walking and sculptural installations to generate dialogues that question climate change, species extinction, urban development, the nature of water transdisciplinarity and ecopedagogy for ‘capable futures’.

Seeking An Ecological Arts Practice

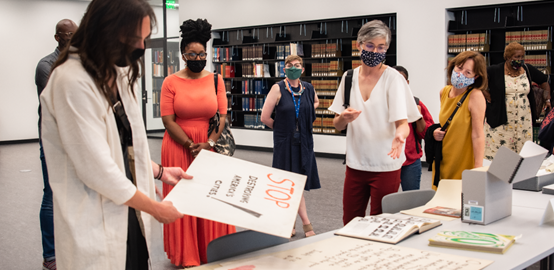

Seeking an ecological arts practice, my Masters in Art As Environment course at Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU) concluded in 1996 with an invitation to project manage and lead the research for Helen and Newton’s Artranspennine98[1] project, Casting A Green Net: Can It Be We Are Seeing A Dragon? The project gave me the opportunity to develop arts-led, practice-based processes of research that opened new ways of questioning the Countryside Information System of The Institute of Terrestrial Ecology[2], and led to my Ph.D.. Mapping the ecosystems of Northern England became a ‘whole systems inquiry’ that included the environmental terrain, agricultural, cultural, and economic contexts, as well as the map-makers intentions. Satellite and field study data was supplemented by many car journeys back and forth, between Liverpool to Hull, to see the terrain and talk with many people from different disciplines and walks of life. Thanks to Professor John Hyatt, the project itself and the production of the six large maps was based at MMU’s Department of Fine Arts. We had regular ‘Open Studio’ events to generate conversations with academic, industry, and civic experts, and arts and design students.

The exhibition opened at Bluecoat Gallery, Liverpool, and in 2000, thanks to Richard Scott of the National Wildflower Centre, was shown at the Society for Ecological Restoration’s (SER) first World Conference, at the Adelphi Hotel, Liverpool. The Harrisons gave a keynote presentation with the work, in the hotel’s capacious lobby. My relationship with SER, as Ecoart Symposium Coordinator/Chair culminated with their World Conference in Manchester in 2015.

In 2005, I was commissioned to curate Evolving the Future, an international three-day conference as part of the Charles Darwin bicentennial celebrations in Shrewsbury. At the end of The Harrisons’ closing keynote lecture, I invited them to consider a project that would focus on mainland Britain as one ecosystem under stress from climate change. We toured the length and breadth of Britain, for a year, meeting many people, to develop a project proposal for potential funders. Finally, Chris Fremantle made a successful application to Defra UK[3], as the Harrisons and I flew to Budapest for a conference. We appointed Chris as Producer and I became Associate Artist. Gabriel Harrison designed and produced the exhibition and the project became Greenhouse Britain: Losing Ground, Gaining Wisdom. It toured six UK venues (2007-2008) and several in the USA (2009-2010), before becoming integrated into the Harrisons’ Force Majeure (2010) works.

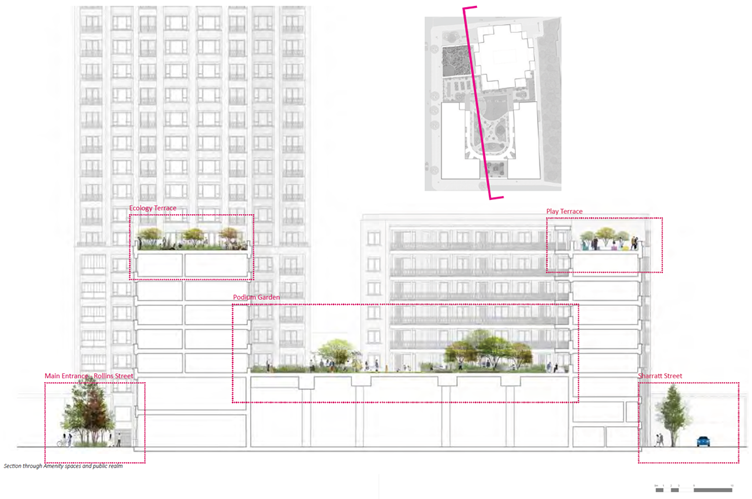

At one point, Defra nearly withdrew Greenhouse Britain’s funding, as they perceived the work to have exceeded the Government’s climate change remit of ‘raising awareness’ to include ‘behaviour change’. We renegotiated the terms of the project to comply with the restrictions, letting the poetics carry the impact further. Meanwhile, a friend from Casting A Green Net, Professor Tony Bradshaw, called me one evening, concerning sea level rise mitigation: “…, but the Environment Agency are developing plans for managed retreat.” I explained that ‘managed retreat’ used engineering and military metaphors, while the Harrisons had coined the phrase, ‘graceful withdrawal’ – metaphors of becoming and acquiescence. And this insight chimed with the Tai Chi concept of ‘yielding’ that has grown through my practice – Yield: give way to gain (Haley 2018). Greenhouse Britain also contained several sub-projects and initiatives including, ecological development of the Lea River Valley, a charrette with Professor Paul Selman’s landscape research students at the University of Sheffield, flood strategies for the River Avon and the River Thames; and opportunities for contained ecological housing/food production to protect the headwaters of all the rivers rising in the Pennines. However, the final UK exhibition at London’s City Hall (2008) met with resistance from the incoming new Mayor of London, Boris Johnson, who saw our work as challenging his proposed Tilbury desalination plant. After a week’s stand-off, Boris Johnson backed down when he realised that the Guardian newspaper was writing an article that depicted his first act as Mayor being the banning of an ecological arts exhibition that offered opportunities to save the Capital from sea level rise.

Through 2007, while working on Greenhouse Britain, the Harrisons and I toured Taiwan to develop the unrealised Greenhouse Taiwan. However, as we toured, we developed the idea of ‘Post-disciplinarity’ ― around a roundtable, all the disciplines sit with equal status while maintaining the integrity of their discipline. Then, the most urgent problem/question of the day is placed at the centre of the table for all to address, together.

We didn’t always agree. And that was one of the ways we learned from each other. They didn’t always agree. And that was one of the ways they learned from each other. Through working, touring, and engaging with Helen and Newton, my ecological arts practice continues to be found and like them, I hope to enable others to seek their ecological arts practices.

References

Firbank, L. Harrison, H. M., Harrison, N., Haley, D. Griffith, B. 2009. A Story Of Becoming: Landscape Creation Through An Art/Science Dynamic in eds. Winter, M. & Loby, M. What is Land for? The Food, Fuel and Climate Change Debate. Earthscan, London.

Haley, D. 2018 Art as destruction: an inquiry into creation, in ed. Reiss, J. Art, Theory and Practice in the Anthropocene. Vernon Press, Wilmington Delaware, and Malaga, Spain.

[1] Artranspennine98 was an initiative between Tate Liverpool and the Henry Moore Foundation, Leeds, to create a corridor of artworks between the two cities. The Harrison saw the ecological opportunity of ‘rhyming the Humber and Mersey estuaries.

[2] The Institute of Terestrial Ecology merged with other environmental research agencies to become the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology.

[3] Defra UK is HM Government’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

John Hyatt

about the writer

John Hyatt

John Hyatt is a painter, digital artist, video artist, photographer, designer, musician, printmaker, author and sculptor. As an artist, Hyatt has exhibited in Australia, Brazil, China, India, Ireland, Portugal, Japan, the UK and the USA. He has a long and varied career and involvement in cultural practices, pedagogy, industry, urban regeneration, and communities. A transdisciplinary theorist, he is a polymath with an interest in arts and sciences.

Strange Attractor of the Harrisons

The Harrisons worked with us for some months. They used the school as a central space for a region-wide investigation, inviting all sorts of experts to collaborate and contribute to an evolving, largely unspecified ecological art/science inquiry. I was interested, amongst other things, in how they kept all parties engaged, brought them together, and kept them involved: the creation of an ecology of collaboration.

I assigned an eco-art Ph.D. student of mine, David Haley, to look after the Harrisons’ needs and to interface with the participating students. The project began with drawing practice. Drawing is a research methodology common to both art and science. Large O/S maps of the area were coloured and re-drawn with the assistance of MA Art as Environment students. The colouring in was to change the emphases of the maps. For example, one map was altered to show only water and watercourses. Through this process, a second stage emerged. The shape of the geographic area of inquiry was made visible and I remember Newton, in front of a wall-sized altered map in the Holden Gallery, chatting with me about whether we were “witnessing a Green Dragon”. The maps created a place where the question could be legitimately asked. They became scenery for an enactment of dialogue. This new, greener dragon flew to the north of the territory of the Welsh Red Dragon. It was anchored in and extended historic cultural narratives. These early stages evolved into the final project title, still interrogative – Casting a Green Net: Can it be we are seeing a Dragon?

The primary drawing stage can be interpreted as ‘Casting a Green Net’. The image of the net came from Helen. She imagined a giant standing at the mouth of the Mersey throwing a fishing net across the Northwest. I always presumed the net was a philosopher’s net made of curiosity.

The second part of the title, ‘Can it be…’ sets up an open invitation to create with no right or wrong answer: a new receptacle. ‘we are seeing…’ invokes a communal act of perception. ‘… a Dragon?’ makes a metaphorical transference of map shape to mythic beast and is pure art, disarmingly naïve seeming, that invites multiple perspectival input from wherever it may derive art or science. It does not require a subject expertise to engage. It is available to children or adults, amateur or expert. The title question created and still creates a level playing field for access to the project.

I just want to dwell on this naming of the project out of these fundamental stages. It seems like a simple thing and so it is. It is also incredibly sophisticated and complex. What this question did going forward was act as a ‘strange attractor’ in the sense of how the term is used in Chaos Mathematics. A ‘strange attractor’ is a simple equation or fractal set that is a root for a complex structure and the pattern of behaviour of a whole (eco) system. Here, there are characteristics of the solution/response already carefully embedded in factors of the equation/question: greenness, community, imagination, and power. The imagist, folkloric question, ‘Casting a Green Net: Can it be we are seeing a Dragon?’, was an auto-generative, immaterial centre around which the fields of inquiry could find their overlapping shape determined by greenness, community, imagination, and power.

I have taken this experience into my own practice. For example, the regeneration of a derelict district of Liverpool by re-drawing it and naming it the Fabric District, emerging from its history, and organising an art/science festival in 2018 for the new District around an open non-intellectual/intellectual concept, Time Tunnel 1968-2018, asking, in a city known for its history of cultural radicalism, What has happened since May 1968?

Looking back down my own time tunnel, I remember the Harrisons with affection and respect.

Petra Kruse and Kai Reschke

about the writer

Petra Kruse

Since 1984 work as art historian (PhD) and editor for various publishing houses and museums, among others, as deputy director of the German Bundeskunsthalle (Federal Hall of Fine Arts); responsible management of numerous international projects; since 2001 development of concepts, project management, budgeting, editing, design and production of exhibitions and books for public and private institutions worldwide together with Kai Reschke.

about the writer

Kai Reschke

Since 1982 work as curator, consultant, designer and organizer of exhibitions on numerous large-scale projects worldwide, many of them emphasizing on arts and ecology; since 1993 lecturing on book and exhibition design, planning, production, technology, didactics, and evaluation in collaboration with various national and international government agencies and universities; since 2001 development of concepts, project management, budgeting, editing, design, and production of exhibitions and books together with Petra Kruse.

Having known, been friends, and worked with the Harrisons for almost 30 years, we discussed, developed, and implemented many projects with them ― exhibitions as well as books: The most important one was probably The Time of the Force Majeure: After 45 Years Counterforce is on the Horizon, a comprehensive retrospective of Helen Mayer Harrisons and Newton Harrisons work (published in 2016).