ESSAYS | POINTS OF VIEW

-

Restoring Sense-Making to Young People (Cyborgs) in Our Techno-Social-Natural World

In late April 2025, I took my Introduction to Geography students outside on the campus front lawn. Working in pairs, students were tasked to do the following: (1)…

-

How Artists Help to Transform Natural Resources Management: Building a theory of change

In the context of the increased complexity of socio-ecological challenges and the growing involvement of arts and culture in climate action (increasingly framed as culture-based climate action), we…

-

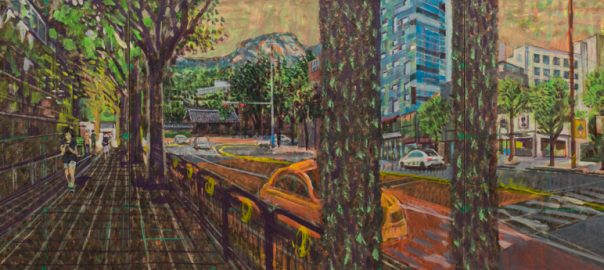

Hopes for My Hometown

“Cities have mythologies”, a colleague mentions offhandedly. There are the smart cities, turning to technologies to improve essential services and respond to challenges. The global cities serve as…

TNOC’S MISSION

Cities and communities that are better for nature and all people, through transdisciplinary dialogue and collaboration.

We combine art, science, and practice in innovative and publicly available engagements for knowledge-driven, imaginative, and just green city making.

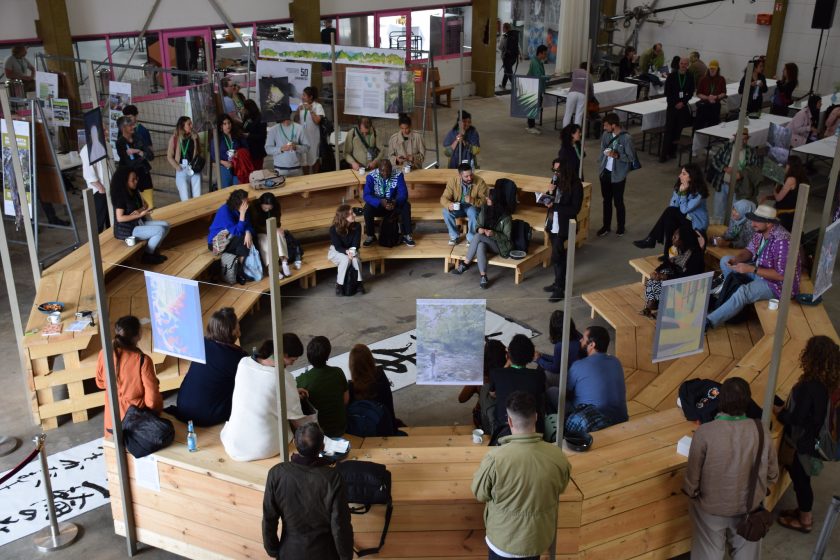

TNOC FESTIVAL IS BACK!

COMING TO COLOMBIA IN 2026

search tnoc

ROUNDTABLES | GLOBAL DISCUSSIONS

SUPPORT BETTER CITIES,

JOIN OUR NETWORK OF DONORS…

REVIEWS | ART, BOOKS & EVENTS

-

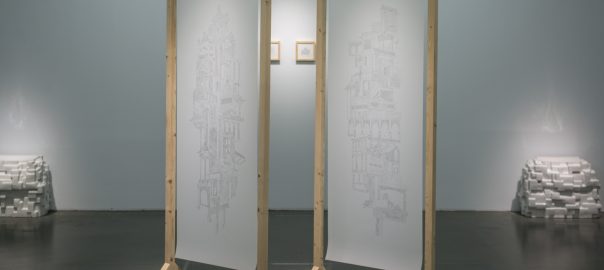

What Remains?

A review of Ghost Ships and Mourning Doves, a multimedia art exhibition by Robin Lasser and Sydney Brown, on view October 1 ― December 13, 2025 at Chung…

PROJECTS | ART, SCIENCE & ACTION, TOGETHER

NBS COMICS: NATURE TO SAVE THE WORLD

26 Visions for Urban Equity, Inclusion and Opportunity

Now a global project with over ONE MILLION readers, we invite comic creators from all over the world to combine science and storytelling with nature-based solutions (NBS).

JOIN THOUSANDS OF READERS

AROUND THE WORLD…

MORE TNOC PROJECTS | ART, SCIENCE & SOCIAL JUSTICE

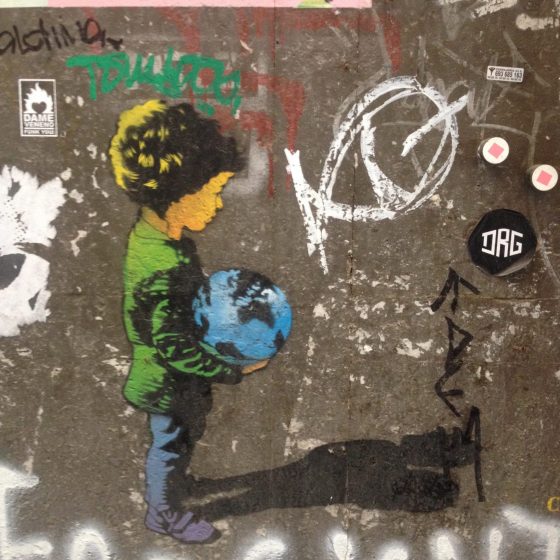

THE NATURE OF GRAFFITI

This is the nature of graffiti. It facilitates speech. It speaks to us. It stakes claims and makes statements. It tells stories.

The Nature of Cities hosts a public gallery about the graffiti and street art that motivates us in public places.

the roots of cool

As the world warms up, how are you thinking about the role that trees and shade can play in making your city or region livable?

Read and listen to the stories in this global collaboration between The Nature of cities & Descanso Gardens.