About the Writer:

Mark Hostetler

Dr. Mark Hostetler conducts research and outreach on how urban landscapes could be designed and managed to conserve biodiversity. He conducts a national continuing education course on conserving biodiversity in subdivision development, and published a book, The Green Leap: A Primer for Conserving Biodiversity in Subdivision Development.

Introduction

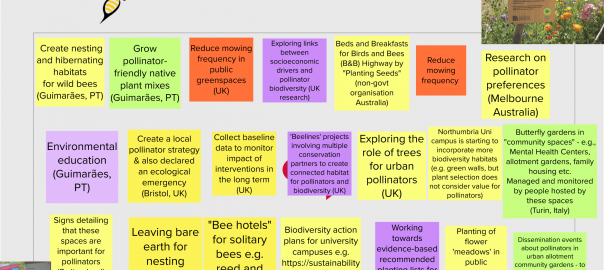

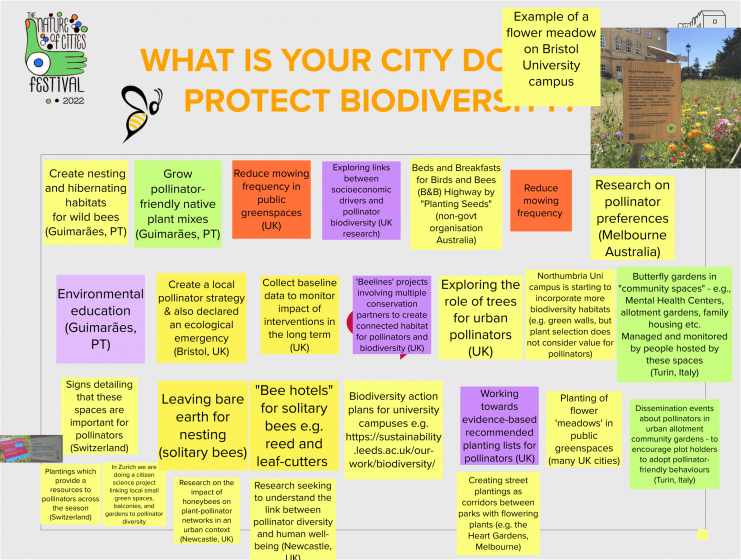

This roundtable discusses examples where city governments, academics, civil society, developers, and/or individuals have become interested in biodiversity, implementing conservation policies, projects, or campaigns.

One conclusion from these examples is this: many approaches can work, from activism to collaboration to city regulation and official biodiversity planning, but they need to be tied together somehow to create comprehensive solutions. Each takes dedication and planning, and must be resonant with the context. Indeed, we might say that lasting success requires action at multiple levels and with multiple stakeholders. City-level action, such as the regulation described in New York or the biodiversity strategy in Surrey, doesn’t happen out of the air; it is the result of years of science, planning, community work, and activism both inside and outside the city administration.

The Paris Metro region’s Agency for Biodiversity created in 2010 an annual competition called “French Capitals of Biodiversity”, which over time has created a rich network of interest for urban biodiversity. Friends groups such a Tualatin Hills (Portland) create plans to and support for biodiversity protection at various levels of society. As Eduardo Guerrero describes in Bogotá: “Effective action depends on a combination of both formal and spontaneous synergies.” All success has a basis in committed leaders, both inside and outside of government, and a coherent sense of collective action.

Activist-leaning academics play a key role, as described in Japan and New Zealand. Such work can form the basis of formal action by the city. “Pracademics” such as Mark Hostetler and Siobhán McQuaid create useful guides and model for collective action by conservationists and developers. Such guides can lead directly to productive collaboration with business leaders. And there is direct activism, such as that described by Kevin Lunzalu in Nairobi.

All these levels have a place and can work—need to work—synergistically to create urban biodiversity conservation that produces results.

The idea of this roundtable is to have examples from all over the world. By exchanging ideas and examples of people working for positive outcomes in biodiversity conservation, people can adapt and try in their own cities.

About the Writer:

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director.

About the Writer:

Eric Butler

Eric Butler is a landscape ecologist and conservation advocate with a particular interest in the urban ecosystems of the Pacific Northwest. He is currently working as a seasonal botanist with the Bureau of Land Management in central Oregon but normally calls the greater Portland area home. He has been a steering committee member with the Friends of Tualatin Hills Nature Park since 2013.

Eric Butler

A walk in the park might reveal anything from pileated woodpeckers to fairyslipper orchids to the park’s unofficial mascot, the rough-skinned newt. Once, though, it was a forgotten piece of land perhaps destined for development. The story of how St. Mary’s Woods became Tualatin Hills Nature Park is a story of community advocacy, driven by passion, persistence, and a collaborative spirit.

The wooded surroundings of the old Elliot Homestead once served as the big backyard playground of St. Mary’s Home for Boys. The land had existed in a state of mostly benign neglect for a long time, but urban expansion was reaching the area, and in the 1970s, the Catholic Archdiocese of Portland was considering selling the property. Several local community members, who had been exploring the site’s network of informal trails for years, wanted to see it preserved. After a bid to gain the interest of Oregon State Parks fell through, attention turned to the nascent Tualatin Hills Park & Recreation District (THPRD), then a traditional turfgrass-and-ballfields operation just beginning to find its identity in a rapidly growing community. At the time, natural resources were barely on THPRD’s radar, and represented a responsibility they lacked the capacity to take on.

Advocates for a nature park were undeterred, and organized to testify at public meetings, rally their neighbors, and eventually pass a bond measure earmarking funds to acquire the park. It would take successive waves of community advocacy, however, to lead to the park’s public opening in 1998; to acquire an additional 22 acres of critical habitat slated for development; and to support dedicated programs and staff for natural resources, trails, and environmental education districtwide. In the half-century since the notion of a Tualatin Hills Nature Park first began, an amazing thing happened: THPRD evolved from reluctant follower to farsighted leader in urban nature conservation. The ensuing years have seen them acquire dozens of new natural areas—more than 150 in all, encompassing about 1500 acres of diverse urban ecosystems including spectacular sites like the scenic oak/prairie landscape at Cooper Mountain Nature Park or the wildlife-rich wetlands at Greenway Park. THPRD’s nature programs serve thousands of preschoolers, summer campers, teens, and adults every year. A thriving volunteer program welcomes community members to restore natural areas and maintain trails most weekends of the year. And, collaborations with other regional agencies have supported metropolitan-scale watershed enhancements.

The community advocates are still around, as well. The original group behind the campaign to acquire the Nature Park evolved first into an advisory committee and, later, to the Friends of Tualatin Hills Nature Park, which remains active to this day. The Friends work closely with THPRD staff to support park improvements and educational programs, using funds raised through their twice-annual native plant sales, and to welcome visitors and volunteers. Though the relationship has grown from one of early tension to a deep and enduring mutual respect, the Friends continue the tradition of advocacy and stewardship that saved an amazing park for the public—and transformed a park district into a regional champion for nature.

About the Writer:

Eduardo Guerrero

Eduardo Guerrero is a biologist with over 20 years of experience in projects and initiatives involving environmental and sustainable development issues in Colombia and other South American countries.

Eduardo Guerrero

Collective action driven by a multi-stakeholder deliberation to conserve urban biodiversity in Bogotá

Within this context let me share some views in response to this relevant question: What actions actually are successful in activating city governments and developers to implement urban biodiversity conservation policies, campaigns, and projects?

Lessons learned in integrating biodiversity into city planning in Bogotá

In this Andean megacity a promising process is taking place, not well coordinated but somehow effective, led by a deliberative group of committed public, private and community groups of interest. My hypothesis is that we are near to achieve in Bogota a critical mass of stakeholders representing a diversity of interests who share a concurrent vision and related goals regarding urban nature.

Effective action depends on a combination of both formal and spontaneous synergies. Local governments are not enough to ensure sustainable transformations. City administrations work on 4-year periods and consequently not ensuring continuity of programs and projects. On the other hand, developers and local communities represent a diversity of interests and expectations, which requires a common umbrella vision to focus on long run effective actions. Unanimity and full agreement are not realistic, considering the existence of some radical and biased positions. So, the recipe to effective action is to reach a critical mass of committed leaders involving a multi-stakeholder common purpose. Even amid conflicts of interest, misunderstandings, and sectoral and political biases, gradually more and more stakeholders value Cerros Orientales, urban wetlands and Bogota river as patrimonial and strategic elements of Bogota´s natural heritage, essential for city prosperity. Some promising achievements, in the middle of a fervent deliberation, show a route of consolidation.

Cerros Orientales, Bogota river and urban wetlands are formally integrated into the Bogotá planning main tool (Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial) and are protected by judicial decrees in response to citizens allegations regarding the right to a healthy environment.

Cerros Orientales is a national protected area (forest reserve) and, as a complement, it was established an adaptation strip (franja de adecuación) in the space between forest reserve and built city. Local government, developers and community organizations must coordinate actions to preserve it.

Regarding the Bogotá river there is also a coordination process among environmental and local authorities in the territory comprising the river basin. Pressures and drivers of river degradation pose one of the biggest challenges toward a stable recovery of the river for the city.

The case for urban wetlands is quite interesting. Thirty years ago, they were not part of city planning. On the contrary, it was a regular practice to filling them with rubble as part of land preparation for housing and urban development. Fortunately, during this interval, a synergistic process involving gov and community stakeholders was successful in halting such an intense deterioration. Now, the complex of urban wetlands has been recognized by Ramsar Convention and local communities value them.

Challenges to consolidate ongoing actions

Of course, some challenges remain to solidify achievements. We need to consolidate a common ground around a shared vision, as well as a win-win mood, in such a way that interests and actions converge and complement. Paradoxically, we have a multiplicity of gov and non-gov similar initiatives under a diversity of organizations competing among them instead of collaborating. It is also critical to promote a governance based on transparency and participation, social appropriation, the building of trust and joint action. A particular challenge is to reconcile opposing political ideologies around common goals and promote city long-term goals ensuring continuity beyond successive administrations.

My conclusion:

Perduring successful actions are those engaging people with urban nature and promoting common goals among diverse public and private stakeholders, that is, actions generating equal and just benefits for all citizens, because of conserving urban biodiversity.

The recipe: social appropriation and a committed set of leaders representing most groups of interest, that work together in a complementary way instead of competing among them.

About the Writer:

Mark Hostetler

Dr. Mark Hostetler conducts research and outreach on how urban landscapes could be designed and managed to conserve biodiversity. He conducts a national continuing education course on conserving biodiversity in subdivision development, and published a book, The Green Leap: A Primer for Conserving Biodiversity in Subdivision Development.

Mark Hostetler

Raising Awareness with Built Environment Professionals about Conserving Biodiversity in Subdivision Development

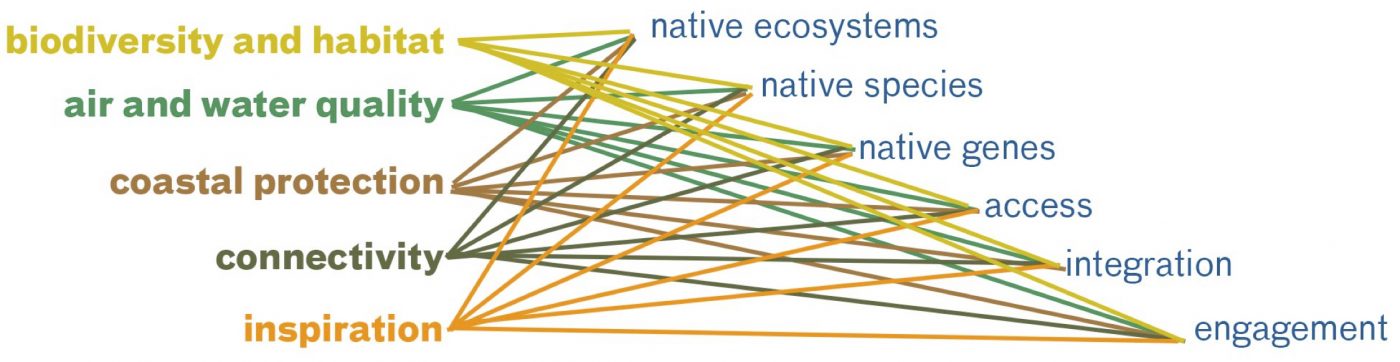

When residential or commercial developments are proposed, there are many opportunities to conserve biodiversity. Primary decision makers that decide whether to implement certain conservation strategies or promote them are typically the development team (i.e., environmental consultants and developer) and city/county planning staff and elected officials. In collaboration with several colleagues and students, I created a 215-page manual called Conserving Biodiversity in Subdivision Development, which outlines biodiversity conservation strategies throughout the development process. This manual was used in trainings or workshops that targeted development teams and city/county planning staff and elected officials.

Also highlighted is how to install low impact development stormwater treatment train for water quality. The last section, post-construction, focuses on long-term management of the homes, yards, conserved open space, and neighborhoods. It discusses education strategies to engage with people in a community and how to fund long-term management plans. Overall, all three phases must be addressed in order to have successful biodiversity conservation over the long term.

How were the decision makers exposed to the manual? We first offered a 4-hour training course for city planners, environmental consultants, and developers. But why did decision makers come to a training? Some came because they were interested in the topic but also, in the United States, the planning and landscape architecture profession requires continuing education units (CEUs) every few years in order to retain certification through their professional societies (e.g., AICP – American Institute of Certified Planners). The course was approved by the professional society and after taking, participants received a CEU certificate. This was an incentive for built environment professionals to come to a training.

Decision makers also became aware of the manual and strategies to conserve biodiversity through our academic consulting group, Program for Resource Efficient Communities (PREC). Developers and environmental consultants, working on a development project, heard about PREC through our various trainings or by word of mouth. Often, they would come to PREC because they wanted to create a conservation development that conserves biodiversity, water, and energy. However, “coming to the table” was often a result of local regulations that emphasize the construction of conservation developments. This highlights the importance of local regulations (and also the importance of raising awareness of local planners and officials!).

The end result of trainings/conversations with developers and environmental consultants is that it planted a “seed” for folks to evaluate a property and strategize on how to implement biodiversity conservation strategies. Through PREC, conservation design and management recommendations were adopted on multiple development projects, from 32 hectares in size on up to 10,000 hectares in size. Some of these developments will house over 50,000 people. Also, trainings and conversations with city/county planners resulted in new policies or ordinances. For example, “no mow” stormwater ponds were proposed in Alachua County, Florida as a way to improve biodiversity and wildlife habitat. However, without appropriate educational signage about the purpose of these no-mow ponds, they were mowed because residents did not like the “look” of them. I proposed installing informational signs around these ponds and the county made this a policy. It worked as ponds with signs are now being maintained more naturally and are not being mowed.

The Conserving Biodiversity in Subdivision Development manual can be translated and adapted to any region or country. Currently, I am working with Professor Keitaro Ito (Kyushu Institute of Technology) and we have translated the manual for the Japanese context, planning to offer multiple trainings in Japan. If interested in adapting the manual for your area, please contact me to discuss ([email protected]).

About the Writer:

Keitaro Ito

Keitaro is a professor at Kyushu Institute of Technology and teaches landscape ecology and design. He has studied and worked in Japan, the U.K., Germany and Norway and has been designing urban parks, river banks, school gardens, and forest parks.

Keitaro Ito, Tomomi Sudo, Hayato Hasegawa

Environmental planning project for establishing biodiversity policy with local government in Japan-

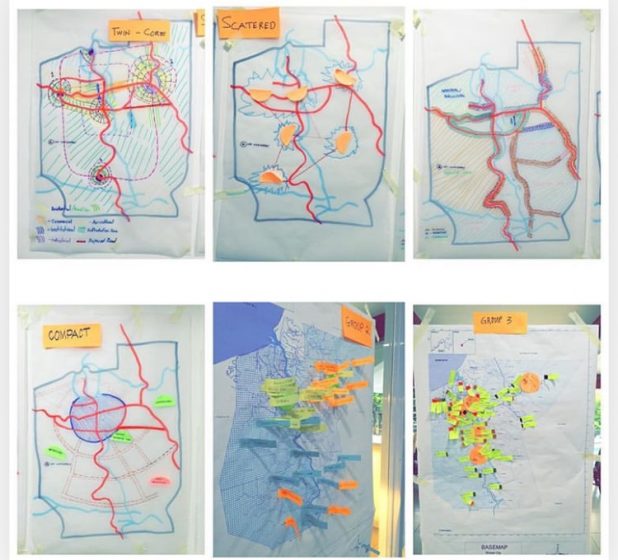

From 2014, we have been taking part in a project in city planning for urban biodiversity in Fukutsu city, Japan. Our lab (Keitaro Ito Lab, Kyushu Institute of Technology) has been directing the project in collaboration with Fukutsu city and high school students from Fukuoka Koryo high school and Fukuoka fishery high school. The project’s origins result from the city government’s desire to make environmental planning part of the basic city planning, resting on the ecological characteristics of the city. They asked us to collaborate for establishing this plan, called the Environmental Master Plan and Regional Biodiversity Strategy.

The plan was completed in 2017. In this plan, we are thinking of sustainability and ecological services very close to our city. As we think of sustainability and biodiversity in the city, the plan will be very important for managing the city environment, but also in sustaining people’s connection to nature. Such connection is a key factor in sustainability, since without knowledge of nature, people will be less engaged with the idea of sustaining nature.

However, it remains a challenge to effectively conserve biodiversity and ecological system services in the city.

Unfortunately, people sometimes don’t realise how the nature they live with is important. A lack of daily connection to nature has become normal for them, a situation one can easily observe in visiting local places in this country. So, one of our important roles is this: How shall we lead the people in a return to thinking about nature in Fukutsu?

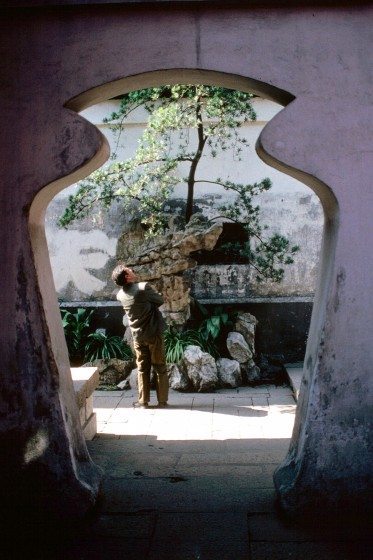

We think it is important to think about the green places for environmental and ecological learning. Each green space has functions in this city, not only as habitat for creatures but also for providing places for ecological learning by children. Landscapes and natural environments afford habitats for play and learning. For example, children are not allowed in some river banks, but if we could evaluate and think of such places in terms of nature restoration and education, such areas could be multifunctional. Therefore, this project also aims to provide natural sites for children’s play and activity. It will help to create places in which young children will have sustained contact with nature in the city.

Around the city, some of the forests have big problems too, such as the expansion of bamboo. Because of the lack of maintenance of forest by people, the forested landscape around the city has changed. As the bamboo comes to dominate the forest, the forest floor is dark in deep shade and other biodiversity is significantly reduced. In such abandoned forests, it is difficult to use for playing and learning place by people and children. The researchers of the Laboratory of Environmental Design have shared and discussed these problems with Fukutsu city’s officers and local people for years in the process of planning. As an implementation of the plans, forest restoration project has been started since 2017.

However, we made plans for planning but sometimes it looks like pie in the sky. In our project, city plans for the environmental and the process of their formulation could be opportunities for building communities that can implement forest restoration contributing to conserve biodiversity and interact people with nature. These processes are intended to enhance social networks and trust among stakeholders and increase social capital for local people’s involvement in forest restoration in Fukutsu city.

Therefore, in association with city environmental management and plans, continuing discussion on how to restore and utilize nature as green infrastructure with various participants has become more urgent in present days. Re-recognizing traditional landscapes as green infrastructure could be given more consideration in city environmental management for regional biodiversity conservation and re-connecting people to nature. Furthermore, it is important to understand how we can invite local people to practical nature restoration activities. The evaluation of social networks among local people and its structure, and management methods for building social capital for regional biodiversity restoration is an issue for the future.

References

Hasegawa H., Sudo T., Lin Shwe Yee, Ito K., and Kamada M. (2021) Collaborative Management of Satoyama for Revitalizing and Adding Value as Green Infrastructure, Urban Biodiversity and Ecological Design for Sustainable Cities , Springer, pp 317-333 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-56856-8_14

Hostetler M (2020) Cues to care: future directions for ecological landscapes. Urban Ecosyst.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-020-00990-8

Hostetler M, Allen W, Meurk C (2011) Conserving urban biodiversity? Creating green infrastructure is only the first step. Landsc Urban Plan.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.01.011

Ito K. (2021) Designing Approaches for Vernacular Landscape and Urban Biodiversity, Urban Biodiversity and Ecological Design for Sustainable Cities , Springer, pp 3-17 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-56856-8_1

Ito K., Fjørtoft I, Manabe T, Masuda K, Kamada M, Fujuwara K (2010) Landscape design and children’s participation in a Japanese primary school – planning process of school biotope for 5 years. In: Muller N, Werner P, Kelcey GJ (eds) Urban biodiversity and design. Blackwell Academic Publishing, Oxford, pp 441–453 https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444318654.ch23

Ito K., Fjørtoft I, Manabe T, Kamada M (2014) Landscape design for urban biodiversity and ecological education in Japan: approach from process planning and multifunctional landscape planning. In: Nakagoshi N, Mabuhay JA (eds) Designing low carbon societies in landscapes. Springer, Germany, pp 73–86 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-54819-5_5

Kamada M. and Inai S. (2021)Ecological Evaluation of Landscape Components of the Tokushima Central Park Through Red-Clawed Crab (Chiromantes haematocheir), Urban Biodiversity and Ecological Design for Sustainable Cities , Springer, pp 199-215 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-56856-8_9

Sudo T., Lin Shwe Yee, Hasegawa H., Ito K. Yamashita T., and Yamashita I., Natural Environment and Management for Children’s Play and Learning in Kindergarten in an Urban Forest in Kyoto, Japan, Urban Biodiversity and Ecological Design for Sustainable Cities , Springer, pp 175-198 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-56856-8_8

About the Writer:

Tomomi Sudo

Dr. Tomomi Sudo studies for developing sustainable cities which can provide essential nature experiences for people and children. She has been implementing ecological learning projects for children in urban natural environment. She is studying also Landscape Ecology and Design in Japan and Norway. Her interest is how to develop the materials for ecological education and apply that for ecological design. She studies at Kyushu Institute of Technology, Japan.

About the Writer:

Hayato Hasegawa

Hayato Hasegawa is a Ph.D. student at Kyushu Institute of Technology, Japan. He implements the collaborations with local government, residents, and children for re-connecting to nature.

About the Writer:

Mahito Kamada

Mahito Kamada is a landscape ecologist working as professor at Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Tokushima University, Japan. His academic interest is on socio-ecological landscape at rural areas in Asia as well as Japan. He is now working as the president of Japan Association for landscape Ecology (JALE). He also works with citizen groups as the representative of a network organization on nature conservation in Tokushima Prefecture, and supports Tokushima prefectural office to make policies on biodiversity conservation.

Mahito KAMADA

An educational course provided to citizen groups for progress in biodiversity conservation

In this essay, I will give an example of actions of citizen groups collaborating with local government to complement the local biodiversity strategy of Tokushima Prefecture, Shikoku, Japan.

Through multiple workshops, the citizen groups recognize that development of human resources is the one of the most important issues for advancing biodiversity conservation. As a result, Tokushima Prefecture set it as one of the key policies in the strategy. At a same time, the network made several education courses and opened them to public. Eight groups in the network provide programs in cooperating with researchers at universities; each group had a specific interest for a particular ecosystem such as natural and semi-natural forest, river, paddy fields, and estuary. Thus, participants in the course can learn about different ecosystems in a basin.

The educational course occurs over eight days. The first day is guidance on entire course and risk management during field works. Each program for the next 6 days has classroom learning and field work as practical training. In the final day, a workshop is conducted to review what was learned. The image below is the flyer for 2021 course, and its contents are as follows: (1) 25 April, Guidance, and risk management in the field; (2) 16 May, Natural Forest and its value for local people; (3) 5 June, wildlife and ecosystem service of river; (4) 4 July, ecosystem of semi-natural forest (Satoyama); (5) 25 July, life and knowledge of local people for using ecosystem services from semi-natural forest (Satoyama); (6) 21 August, wildlife in paddy fields and irrigation channel; (7) 5 September, wildlife and ecosystem function of estuary; (8) 24 October, workshop for reviewing what was learned.

The quality and quantity of the education is very high, it may be comparable to 2 units of a practical training class in an undergraduate program of a university, and thus it has been qualified as an official course by the government of Tokushima Prefecture. As a consequence, the prefectural office has started to pay 900,000 Japanese yen (ca.$US8,500) a year to the network as costs of conducting the course, and a person who completes the course has been qualified as a “biodiversity leader” by the Governor. Some of the biodiversity leaders join the staff for the educational course and learn ways to manage and teach a course, acting as lecturers. These courses are a result of efforts for development of human resources over a seven-year period.

As an example of impacts from the course, in the final workshop in the course of 2020, a middle-aged lady, who is strawberry farmer, said that she learned about the important role of an estuary and recognize pesticides she uses are a risk to an estuary. She immediately decided to reduce pesticides in her farm.

About the Writer:

Marit Larson

Marit Larson is the Chief of the Natural Resources Group (NRG) at NYC Parks. NRG manages over 10,000acres of natural areas including forests, grasslands and wetlands, stormwater green infrastructure and a native plant nursery.

Marit Larson, Georgina Cullman, Clara Holmes, Matthew Morrow

Promoting Biodiversity in New York City through Native Plants

New York City, despite being a densely developed metropolis of over 8.4 million people, has made a commitment to protecting biodiversity through both practice and policy. One example is the Native Plant Law, which promotes biodiversity through mandating the use of native plants in public landscapes. This law is significant, less as a stand alone measure, but because it rests on a history of critical actions, partnerships, and commitments to protect biodiversity at different scales in NYC. Similarly, its effectiveness relies on ongoing efforts to protect open space and manage the health of our natural areas.

Today, Freshkills Park boasts an expanse of grasslands that has welcomed back several rare and declining grassland bird species. Concurrently, NYC Parks pledged to invest in biodiversity with the establishment of the Greenbelt Native Plant Center (GNPC). This municipal nursery, the largest in the country, collects seed of native species from the NYC area, and has pioneered the propagation and use of native plants. These species increase the plant diversity available for local restoration projects. Twenty years after GNPC’s establishment, NYC Parks has refined a diverse palette of native species that are successful in various restoration and landscaping projects and GNPC staff regularly provide recommendations to designers and practitioners.

Today, Freshkills Park boasts an expanse of grasslands that has welcomed back several rare and declining grassland bird species. Concurrently, NYC Parks pledged to invest in biodiversity with the establishment of the Greenbelt Native Plant Center (GNPC). This municipal nursery, the largest in the country, collects seed of native species from the NYC area, and has pioneered the propagation and use of native plants. These species increase the plant diversity available for local restoration projects. Twenty years after GNPC’s establishment, NYC Parks has refined a diverse palette of native species that are successful in various restoration and landscaping projects and GNPC staff regularly provide recommendations to designers and practitioners.

In 2007, PlaNYC, the first sustainability plan for New York City, energized greening initiatives in the city. Increased focus on the importance of ecological services from a variety of governmental and nongovernmental organizations led to the passing of various green codes and laws (from zoning to stormwater management), including the first Native Plant Law in the City (§ 18-141 NYC Admin. Code). This law mandates maximizing the use of native plants and reducing the use of invasive non-native species in public landscapes. The law requires the publication and regular updating of NYC’s Native Species Planting Guide (NSPG), which provides native species planting lists for NYC habitats and native alternatives for common invasive plants.

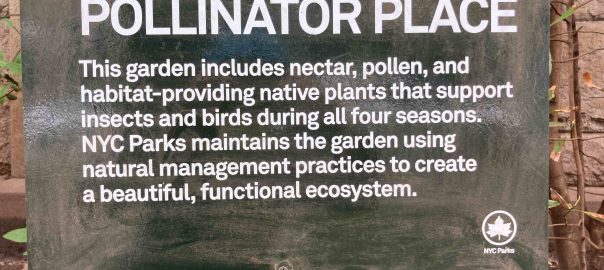

Within NYC Parks, the planning guide has been a resource for landscape architects and city gardeners. The ready availability of species lists by habit and growth form in the NSPG, coupled with knowledge about current and historical plant communities in the city, has resulted in additional programs to promote biodiversity at an intermediate scale. For example, in accordance with the Forever Wild Program, only native street trees are planted within 100 feet of natural areas and no trees listed as “problematic” in the guide are planted within 500 ft of natural areas. The NSPG is also improving biodiversity in our landscaped parks. In 2020, NYC Parks launched “Pollinator Places”—public-facing horticultural beds primarily made up of attractive native plants, with the intention that they would serve as educational opportunities for the public and as bridges for gardeners used to working with non-native plants.

The Native Species Planting Guide also has the potential to advance biodiversity goals even beyond the boundaries of NYC Parks. For example, in special zoning districts in Staten Island, proposed policy will encourage homeowners to plant native trees, and disincentivize the planting of non-native problematic species, citing the NSPG as a resource.

Urban areas are increasingly recognized as valuable corridors between larger natural habitats, and as refugia in and of themselves; thus, promoting biodiversity within cities is critical. Though NYC has had success in doing so at various levels, challenges remain. For example, native plant supply and availability are often not considered early enough in planning. Additionally, rules on maintaining landscaped areas are often at odds with ecological best practices, and on-going invasive species management needs are not considered. NYC Parks continues to work to meet these challenges to sustain biodiversity within our city.

About the Writer:

Georgina Cullman

Georgina Cullman, Ph.D. is an Ecologist for New York City's Department of Parks & Recreation. As part of NYC Parks Natural Resources Group, Dr. Cullman conducts research and provides advisement to protect and enhance the city's natural areas and biodiversity.

About the Writer:

Clara Holmes

Clara Holmes is a Field Scientist with NYC Parks, specializing in Botany. Most of her field work consists of monitoring vegetation pre and post restoration, and tracking rare plant populations in NYC Parks. She holds a Master’s of Science from Pace University and Bachelor's of Arts from the College of Charleston.

About the Writer:

Matthew Morrow

Matthew Morrow is the Director of Horticulture at Forestry Horticulture and Natural Resources, a division of the NYC Park's Department. In this role he works to educate and support the gardeners and gardens of the agency, as well as the various native flora and fauna of New York City.

About the Writer:

Kevin Lunzalu

Kevin Lunzalu is a young conservation leader from Nairobi, Kenya. Through his work, Lunzalu strives to strike a balance between environmental conservation and humanity. He strongly believes in the power of innovative youth-led solutions to drive the global sustainability agenda. Kevin is the country coordinator the Kenyan Youth Biodiversity Network.

Kevin Lunzalu

Nairobi’s green spaces saved through environmental and cultural activism

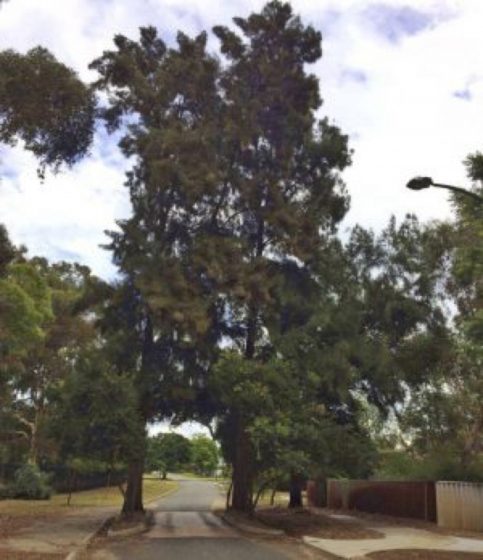

Known as the green city in the sun, the Nairobi Metropolitan area is home to some of the oldest individual trees in East Africa. A case in point is the iconic fig tree that is located along Waiyaki Way, west of Kenya’s capital city, that is estimated to be between 125 to 150 years old. This particular species not only carries ecological significance to Nairobi’s urban population, but also cultural importance to various communities in Kenya.

The Maragoli people have for a long time held the fig tree, known to them as “mukumu”, to be a symbol of peace, under which conflicts are resolved. Additionally, many tribes in Kenya still use fig trees as boundary markers. Nairobi’s oldest fig tree caused environmental and cultural uproar in equal measures, in early 2020, when it wasearmarked for uprooting to pave way for the construction of the Nairobi Expressway.

In the quest to ease traffic congestion in Nairobi, traffic which costs the government an estimated $1.8 million annually worth of revenue, Kenya’s capital is in the race to construct a 27 Kilometer expressway that will connect the city’s Jomo Kenyatta International airport and Waiyaki Way in Westlands. Upon operationalization, motorists are expected to spend only about 15 minutes moving between these two points, a reduction from about 2 hours currently spent.

However, the $550 million project has come with adverse environmental costs, with hundreds of trees located along the route cut down, including the native Nandi flame species, which were reportedly planted in the 1990s. This permanent degradation of ecological lifeline and cultural values that some of these trees carried is what called for action from activists and other lobby groups, at least to save the most iconic ones, like the now-famous fig tree.

Environmentalists, cultural activists, and several urban dwellers took to the streets amidst the increasing need to stay at home due to the COVID-19 pandemic, to stop the government from uprooting the iconic fig tree. This followed months of deforestation by the Chinese-funded project that ripped the city of its most treasured green spaces.

Youth-led organizations such as the Kenyan Youth Biodiversity Network spearheaded campaigns to call for immediate action from the government to save the coveted fig tree and other green urban spaces in Nairobi. An online campaign was also set up directly engaging government entities including the Kenya National Highways Authority to spare the tree that supports a myriad of bird life and other species. A petition to call for protection of the tree was signed by thousands of people.

“We are demanding that the city government listens to the environmental and cultural aspirations of its people, and reroute the road,” Jackem Otete, a grassroot coordinator at the Kenyan Youth Biodiversity Network said during a street match.

The outcry by members of public, environmentalists, and activists pressured the city government, resulting in a presidential decree to protect the threatened fig tree. In a press conference addressing the issue, Mohamed Badi, the Director General of the Nairobi Metropolitan Services said: “It is now a presidential declaration that this [fig] tree will now be conserved.” The order forced the national highways authority and the Chinese contractor to reroute the ExpressWay.

“..that pursuant to Article 69 of the constitution, as read together with section 3 of the Environment Management and Co-ordination Act and all other enabling laws, this fig tree is hereby adopted by the Nairobi Metropolitan Services on behalf of the people of Nairobi..” read the declaration in part.

On eve of Christmas 2020, the president decorated the fig tree with lights to symbolize its significance and wish Kenyans well during the festivities. Since the presidential declaration, several conservation organizations have emerged, calling for protection of other green spaces in the city.

About the Writer:

Siobhán McQuaid

Siobhan is the Associate Director of Innovation at the Centre for Social Innovation in Trinity College Dublin where she heads up research and innovation activities under the themes of sustainability and resilience.

Siobhán McQuaid

Green buildings for biodiversity—who are the industry leaders?

The European Commission identifies nature-based solutions (NBS) such as green buildings as solutions “inspired and supported by nature, which are cost-effective, simultaneously provide environmental, social and economic benefits and help build resilience. Such solutions bring more, and more diverse, nature and natural features and processes into cities, landscapes and seascapes, through locally adapted, resource-efficient and systemic interventions. Nature-Based Solutions therefore provide multiple benefits for biodiversity.”

We know from research in the UK and Switzerland that well designed green roofs can contribute to biodiversity with wildflower roofs being particularly attractive for insects and pollinators such as bees (Livingroofs.org). However while the market for green buildings is growing rapidly in some parts of Europe it is lagging behind in others. Rodolphe Deborre, Director of Innovation and Sustainable Development at the French construction giant Rabot Dutilleul pointed out that in France the construction sector lacks knowledge and therefore trust in nature-based solutions. In an industry traditionally driven by price there are many questions: how much will nature cost in the short and long term? Will the client pay extra for nature? How effective are NBS? Are they allowed under current regulations? In an industry driven for centuries by hard engineering and physics, there is little knowledge of ecology or nature and therefore little trust in it.

In contrast in Austria, the government has played an important role in stimulating both demand and supply for green buildings. Over 550 businesses are active in this sector supported by strong and supportive government policy including market incentives and a mobile outreach programme (MUGLI) which introduces people to a vivid first-hand experience of greening buildings. A climate certification scheme managed by Grünstattgrau (the national competence centre for green buildings) is in place which developers can use to demonstrate market leadership. In Austria this kind of certification is seen as a competitive advantage —certified companies are industry front-runners. Research shows that they can charge 8% more for buildings with green infrastructure so there’s a strong business case for investment.

But the changes needed go deeper than policy support and market incentives. Systemic change is needed throughout the education and innovation system to generate a new breed of architect, developer and investor who know as much about ecology as they do about engineering and business. Researchers can provide vital support—proving the effectiveness of nature-based solutions and helping to reduce costs with new technologies. Unfortunately this kind of systemic change takes time. And with the current pace of climate change and biodiversity loss, time is not on our side. In the immediate short term, industry pioneers are needed to show leadership and demonstrate that NBS can work. Where the leaders go, others will follow…

The retail sector can play an important leadership role working with urban planners to envisage new city districts co-created with communities in mind. Johanna Cederlöf of IKEA explained how IKEA developed the plans for their new building at Vienna Westbahnhof in close cooperation with the local community. The community wanted more nature so the IKEA building was designed as a park which people can access even without coming into the store. IKEA have taken a similar community co-creation approach in other cities opening up green roofs to citizens in London, putting football pitches for the community on the roof in Eindhoven and public playgrounds on the roof in Utrecht. The possibilities are endless. Will other retailers and developers follow these examples and re-examine the possibility of green buildings—for communities and for biodiversity?

About the Writer:

Colin Meurk

Dr Colin Meurk, ONZM, is an Associate at Manaaki Whenua, a NZ government research institute specialising in characterisation, understanding and sustainable use of terrestrial resources. He holds adjunct positions at Canterbury and Lincoln Universities. His interests are applied biogeography, ecological restoration and design, landscape dynamics, urban ecology, conservation biology, and citizen science.

Colin Meurk

A game of two halves—the personal journey.

The aspirations may be undone by career bureaucrats who don’t know that they don’t know; so outside the tent it becomes more who you know rather than what you know. It seems society has lost its innate ecological literacy (dis-enfranchisement, institutional memory loss, guardianship), maybe retaining a sense nature is important at some metaphysical level, but often, in ecology and conservation, the devil is in the detail.

We are of course dealing with different motivations for politicians (e.g., votes—a bit simplistic and cynical), bureaucrats (performance/promotion), and community/environmental advocates (global to local sustainability/well-being outcomes). But everyone has multiple agendas—personal, family, “group”, city, nation, or the team of 5 billion. New Zealand made a virtue out of being the team of 5 million in containing the Covid crisis. But it is hard to sustain the collective will when it is undermined by fake news on social media or mainstream shock jocks.

There is also mismatch between what is commonly understood by environment and ecology. The 3rd pillar of sustainability is most often stated as environment, rather than ecology. Technically environment covers the living world, but in popular use it seems primarily to relate to clean air and water, e-cars, solar panels, thermally efficient buildings, etc., in other words, “life” seems to be missing or an afterthought. So, we will choose street trees, from anywhere in the world, that have regimental growth forms, over an indigenous more scruffy tree form, without considering the loss of landscape wildlife functionality, place-making, legibility, and cultural connectivity.

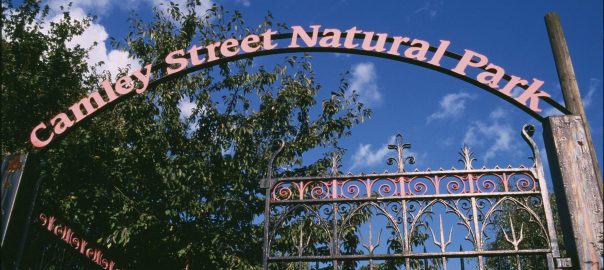

Back to the question, we can all point to pockets of at least partial success and sanity. Christchurch City’s Travis Wetland park, protected in 1997, resulted from a juxtaposition of respected community campaigners backed by young ecologists, a champion council planner with experience of the international wetland conservation movement, a sympathetic elected Council, a deal with a developer, and subsequently a hands-on park ranger who has been fully engaged, working with a community trust in partnership. We have also endeavoured to copy London’s Biodiversity Partnership as a means of direct conversation, peer review, and mutual support between council staff and able, concerned citizens bypassing the charade of exhausting and fruitless annual plan submissions. Ratification is still pending! Now, the National Park City (biophilic) provides a brand to promote common vision, cohesion and interdepartmental synergy—if the city can be pro-active with “can-do” attitude.

It seems activist youth is having some impact around the world, dragging leaders kicking and screaming into taking urgent climate action. But there are powerful business-as-usual lobbyists who will prefer cosmetic or token changes to the needed fundamental reset of the prevailing economic paradigm. Thriving nature in cities and connection to people’s daily experience (e.g., Shinrin yoku) will be a vital component—for benefits to human physiology, psychology, well-being and reduced material consumption. Nature is a great teacher and we are drawn to it. We need to get more of our zest and lessons from nature so we can be better planetary citizens and guardians. Even if we know there won’t be immediate correction, we have to bring what to many will be unpalatable ideas into the conversation so when required it isn’t a total shock.

About the Writer:

Pamela Zevit

My career path has reflected a passion for affecting change and has helped to culture long-lasting relationships with a diversity of government and non-government, academic, conservation and sustainability leaders and industry interests. Goals: To build a legacy of ecological literacy and stewardship among decision makers and local citizenry through reconciling the conflicts between human and non-human resource needs and improving the trust between society and science practitioners.

Pamela Zevit

City of Surrey Biodiversity Conservation Strategy: How did this happen?

The BCS was completed and endorsed by Council in 2014. The Strategy acts as a framework to establish biodiversity goals and targets and conservation priorities for the City as part of an ongoing initiative originating from the City’s Sustainability Charter, adopted in 2008 (and updated in 2016). The BCS is intended to work in conjunction with the City’s Official Community Plan.

What were the ingredients that helped to raise awareness about biodiversity within the government or development team that led to a new biodiversity policy or project?

What were the ingredients that helped to raise awareness about biodiversity within the government or development team that led to a new biodiversity policy or project?

As with many jurisdictions, a key portion of high biodiversity areas within the City are located on private land. This limits the powers of the City in respect to imposing restrictions on development. In order to successfully establish support for the development of the BCS, and the subsequent establishment of the GIN, the cooperation and engagement of a broad spectrum of stakeholders was essential. To facilitate this, the City established a Stakeholder Working Group made up of 18 key community stakeholders from business and environmental groups, First Nations, neighbouring governments, and other partners.

The working group met four times throughout the process to provide feedback and recommendations. Public communication was ongoing throughout the development of the strategy, including regular press releases, use of social media, and public open houses and information sessions.

The BCS and GIN are recognized and interwoven in many of the City’s key strategic documents: Parks, Recreation & Culture Strategic Plan; Integrated Stormwater Management Plans; Shade Tree Management Plan; Coastal Flood Adaptation Strategy; Climate Adaptation Strategy; Newton: Sustainability in Action Plan; and the City’s overarching Sustainability Charter.

What collaborations or processes, initiated by someone inside the government (city staff or elected official) and/or outside the government (academic, scientist, activist), led (or will lead) to new biodiversity conservation policies or actions?

To help further existing efforts to meet the intended objectives of the BCS, the City hired a Biodiversity Conservation Planner in 2019, whose role is to oversee implementation of the BCS at both a planning and operational level. One type of conservation target in the BCS is tracking indicator species. Starting in 2019 the City began accessing community science data through iNaturalist; it is using the platform to acquire and map data about where, and when various species occur across Surrey. Realtime data such as this has been valuable in identifying species at risk, newly detected invasive species, and various regulated species (e.g., migratory birds and raptors), information which the City can apply to inform land use planning—from the site to the landscape level (e.g., specific DPs up to neighbourhood plans).

The City is also partnering with the University of British Columbia to determine the best approaches and software tools to analyze various landcover data (e.g., Metro Vancouver’s Sensitive Ecosystem Inventory and the GIN) in an attempt to build a more comprehensive picture of priority conservation lands.

Beginning in 2021, the City is increasing the City-wide Parkland Acquisition development cost charge (“DCC”) rate with the goal of providing funding to acquire GIN lands identified in the BCS. The increase will be phased in over 5 years. Approximately 441 hectares of GIN lands must be acquired, at an estimated cost of $1 billion over the next 50 years (roughly $20 million per year at present land values). Approximately 75% of GIN lands are within developable areas, thus are DCC eligible. The DCC was fully approved by the Province and Surrey’s Mayor and Council as of April 2021 and will go into effect in May 2021.

Ultimately, successful implementation of the BCS is tied to political will, long-term support from the community and how broader societal values recognize the importance of nature as integral to a City’s health, well-being and resiliency.

Check out Biodiversity Conservation in Surrey to learn more.

About the Writer:

Gilles Lecuir

Expert en écologie urbaine, en communication publique et en politiques publiques, Gilles Lecuir travaille pour l’Agence régionale de la Biodiversité en Île-de-France et anime le concours national Capitale française de la Biodiversité. // Expert in urban ecology, public communication and policies, Gilles Lecuir works for the Paris Region Agency for Biodiversity and animate the French Capital of Biodiversity Award.

Gilles Lecuir

Les « Capitales françaises de la Biodiversité » : des exemples inspirants

L’aspect « compétition » est une motivation certaine pour les élus et les techniciens des villes participantes, qui aspirent à obtenir une reconnaissance nationale, outil puissant pour valoriser l’action politique auprès de leur population. Pourtant, avec 80 villes participantes en moyenne et seulement 5 à 6 lauréats chaque année (1 par catégories de taille de ville et 1 champion toutes catégories confondues, la victoire n’est à l’évidence pas la seule motivation à participer.

L’aspect « compétition » est une motivation certaine pour les élus et les techniciens des villes participantes, qui aspirent à obtenir une reconnaissance nationale, outil puissant pour valoriser l’action politique auprès de leur population. Pourtant, avec 80 villes participantes en moyenne et seulement 5 à 6 lauréats chaque année (1 par catégories de taille de ville et 1 champion toutes catégories confondues, la victoire n’est à l’évidence pas la seule motivation à participer.

En effet, le concours est conçu d’abord comme un outil pédagogique, d’une part au travers d’un questionnaire exigeant et qui est une véritable source d’inspiration, d’autre part par l’édition de recueils thématiques d’actions exemplaires qui garantit à toutes les villes participantes de pouvoir partager et diffuser une ou plusieurs réalisations dont elles sont fières.

Et puis, au fil du temps, un réseau informel s’est constitué : des personnes motivées, engagées mais aussi expérimentées, performantes, innovantes, qu’elles soient techniciennes, politiques, expertes ou encore chercheuses. Journées d’échanges, visites inspirantes sur le terrain, partage de documents ou de conseils sont devenues courantes, sans se substituer aux réseaux formels (qui sont des partenaires fidèles du concours) mais bien en complément de leur action.

Le concours Capitale française de la Biodiversité ne s’intéresse qu’aux actions réalisées, déjà mises en œuvre, pas aux projets. Car c’est une pédagogie par la preuve qui est recherchée : il s’agit de donner envie aux maires de se lancer dans des actions de préservation ou de restauration de la biodiversité locale, de les rassurer sur la faisabilité de leurs projets et de leurs faire gagner du temps en leur permettant de s’appuyer sur les acquis de leurs collègues. Voici quelques exemples d’actions de lauréats de ces dernières années :

A Strasbourg (Alsace), la ville vient d’obtenir le classement d’une de ses forêts alluviales bordant le fleuve Rhin en Réserve Naturelle Nationale, le plus haut degré de protection légale en France. Et c’est sa 3e réserve naturelle urbaine ! Pour le milieu urbain plus ordinaire du point de vue de la biodiversité, la ville déploie des Parcs Naturels Urbains, par quartier : un concept qui mobilise autour des enjeux de nature en ville les citoyens, les associations, les entreprises…

A Lille (Nord), une ville très dense et minérale, on ouvre des fosses de plantation dans les trottoirs afin de permettre aux riverains d’y planter des plantes grimpantes qui vont pousser le long des façades formant une végétalisation verticale naturelle, peu coûteuse, facile à entretenir et qui participe à rafraichir les rues en cas de canicule. Un mouvement initié il y a plus de 20 ans mais qui s’accélère : des centaines de façades publiques comme privées sont désormais végétalisées chaque année…

A Rennes (Bretagne), un vaste parc naturel vient d’être créé en centre-ville, pour offrir à la fois des espaces de jeu, de promenade et de détente aux citadins, mais aussi pour offrir dans des zones non-accessibles un refuge à une faune et une flore mises sous fortes pression par les activités humaines. Et le tout constitue une nouvelle d’expansion des crues de la rivière : inondé quelques jours par an, le parc protège les habitations voisines et constitue une zone humide très favorable à un large cortège d’espèces. Un bel exemple de solution fondée sur la nature pour limiter les risques.

Enfin, depuis 2019 le concours s’appuie sur une démarche supplémentaire qui vise à aider les villes comme les villages qui ne sont pas encore des « champions de la biodiversité » à structurer leurs projets de protection de la nature, à en amplifier l’ambition comme la qualité, à aider à leur réalisation. C’est la reconnaissance « Territoire engagé pour la nature ». Et en toute logique, on espère que ces projets deviendront dans quelques années des actions exemplaires évaluées et valorisées grâce au concours « Capitale française de la Biodiversité…

Pour en savoir plus :

http://www.capitale-biodiversite.fr/

https://engagespourlanature.biodiversitetousvivants.fr/territoires

The “French Capitals of Biodiversity”: inspiring examples

The “competition” aspect is a definite motivation for elected officials and technicians of the participating cities, who aspire to obtain national recognition. Such an award is a powerful tool for enhancing the value of their political action among their population. However, with an average of 80 participating cities and only 5 to 6 winners each year (one award per city size category and one champion in all categories), victory is obviously cannot the only motivation to participate.

The “competition” aspect is a definite motivation for elected officials and technicians of the participating cities, who aspire to obtain national recognition. Such an award is a powerful tool for enhancing the value of their political action among their population. However, with an average of 80 participating cities and only 5 to 6 winners each year (one award per city size category and one champion in all categories), victory is obviously cannot the only motivation to participate.

Indeed, the competition is designed first and foremost as an educational tool, on the one hand through a demanding questionnaire that is a real source of inspiration, and on the other hand through the publication of thematic collections of exemplary: actions that ensure that all participating cities can share and disseminate their achievements, of which they are proud.

Over time, an informal network has been formed: of motivated and committed people, but also experienced, effective, and innovative municipal workers, whether they are technicians, politicians, experts, or researchers. Exchange days, inspiring field visits, and sharing of documents or advice have become commonplace, without replacing other formal networks (which are faithful partners of the competition) but rather complementing their action.

The French Capital of Biodiversity award is only interested in actions that have already been implemented, not in projects that are not yet complete. The aim is to encourage mayors to take action to preserve or restore local biodiversity, to reassure them that their projects are feasible, and to save them time and resources by allowing them to build on the achievements of their colleagues.

Here are a few examples of actions by award winners in recent years:

In Strasbourg (Alsace), the city has just obtained the classification of one of its alluvial forests bordering the Rhine River as a National Nature Reserve, the highest degree of legal protection in France. And this is the city’s 3rd urban nature reserve! For the more ordinary urban environment, from the point of view of biodiversity, the city is deploying Urban Nature Parks, by district: a concept that mobilizes citizens, associations, companies, etc. around the issues of nature in the city.

In Lille (Nord)—a very dense and mineral city—planting pits are opened in the sidewalks to allow residents to plant climbing plants that will grow along the facades, forming a natural vertical vegetation. These are inexpensive, easy to maintain and help to cool the streets during heat waves. This is a movement initiated more than 20 years ago but which is accelerating: hundreds of public and private facades are now being greened every year.

In Rennes (Brittany), a vast natural park has just been created in the city center, which provides play areas, walks, and relaxation for city dwellers, but also provides a refuge for fauna and flora in non-accessible areas that have been put under great pressure by human activities. The park also serves as an expansion of the river flood zones: flooded a few days a year, the park protects the neighbouring houses and constitutes a wetland very favourable to a wide range of species. Thus, it is a good example of a nature-based solution to limit risks.

Finally, since 2019, the competition has been based on an additional approach that aims to help cities and villages that are not yet “biodiversity champions” to structure their nature protection projects, to amplify their ambition and quality, and to help with their implementation. This is the “Territory Committed to Nature” recognition. Naturally, we hope that in a few years such projects will become exemplary actions that will be evaluated and promoted as part of the “French Capital of Biodiversity” competition.

To find out more:

http://www.capitale-biodiversite.fr/

https://engagespourlanature.biodiversitetousvivants.fr/territoires

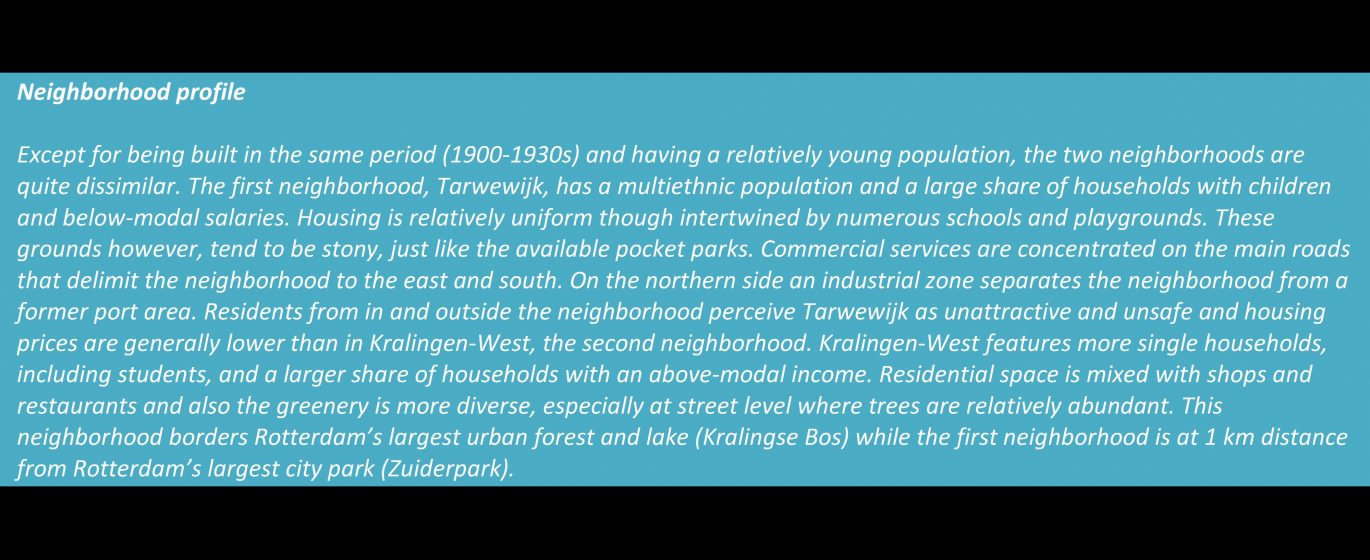

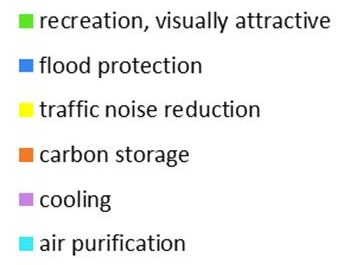

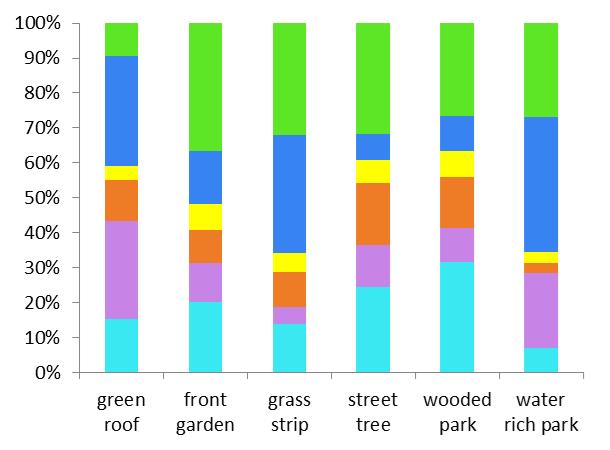

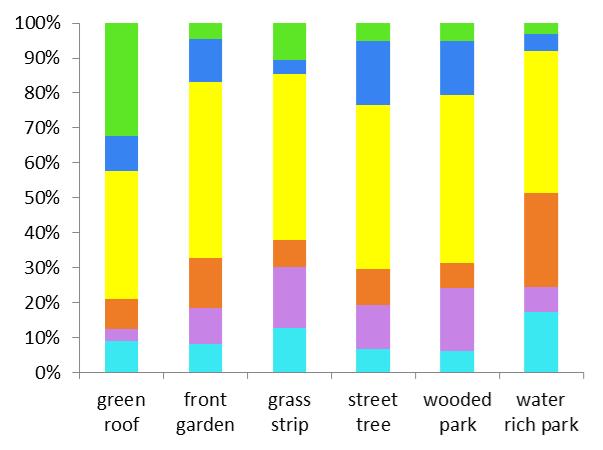

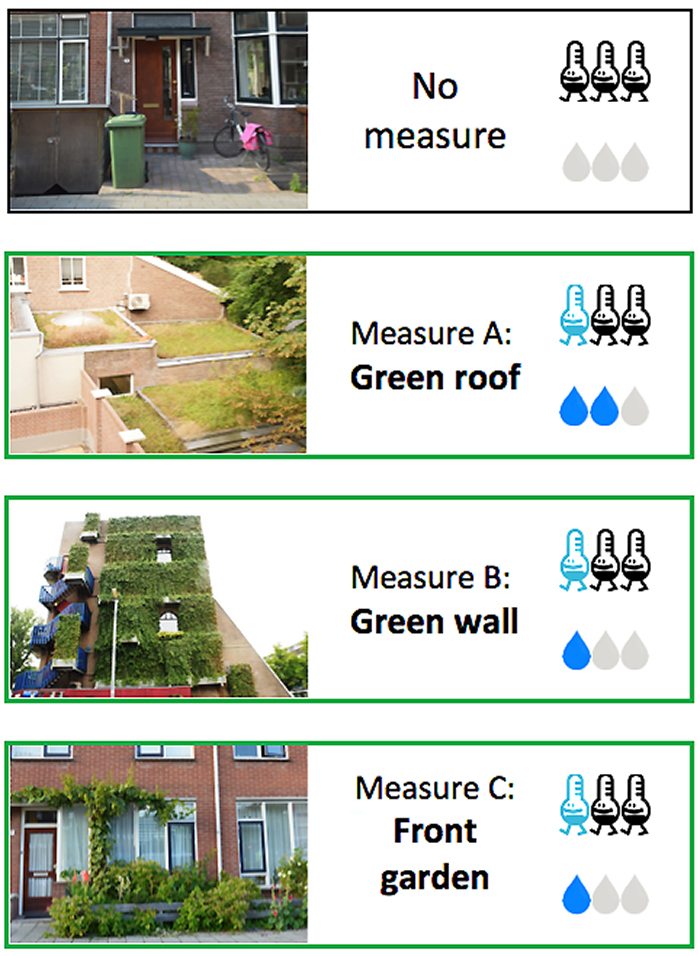

People are aware of urban heat and flooding and consider these serious future challenges, but do not always realize how greenery may support climate adaptation. We asked residents to name the two most and two least important benefits related to six different green space types (see figure). Green space benefits with a more direct effect on people’s health and well-being, such as recreation and air purification, are better understood than less direct benefits, such as temperature regulation. Traffic noise reduction was considered the least important benefit of each green space type.

People are aware of urban heat and flooding and consider these serious future challenges, but do not always realize how greenery may support climate adaptation. We asked residents to name the two most and two least important benefits related to six different green space types (see figure). Green space benefits with a more direct effect on people’s health and well-being, such as recreation and air purification, are better understood than less direct benefits, such as temperature regulation. Traffic noise reduction was considered the least important benefit of each green space type.

The following two examples depict boats tossing in stormy seas, a strong narrative of shared, collective history in Cape Town, which was originally known as the Cape of Storms. Even today ships run aground on the shores of the City every winter and this is an aspect of nature we all share and respect.

The following two examples depict boats tossing in stormy seas, a strong narrative of shared, collective history in Cape Town, which was originally known as the Cape of Storms. Even today ships run aground on the shores of the City every winter and this is an aspect of nature we all share and respect.

Pictures of African wildlife, not present in Cape Town for hundreds of years, litter the city, calling on the larger urban populations to take up these distant conservation causes.

Pictures of African wildlife, not present in Cape Town for hundreds of years, litter the city, calling on the larger urban populations to take up these distant conservation causes.

The following graffiti is regularly updated, keeping abreast of the shocking rhino death tolls due to poaching for the illegal horn trade in conservation areas far flung from Cape Town.

The following graffiti is regularly updated, keeping abreast of the shocking rhino death tolls due to poaching for the illegal horn trade in conservation areas far flung from Cape Town.

Concrete-built Brutalism has left its mark in our urban environments. Biophilic design as informed by women can foster healthier and more beautiful places and holds the potential to rectify the negative impacts that brutalist architecture descending from modernist planning has codified in sterile and unsociable housing schemes. By reweaving broken links, fostering local food systems, and coevolving lively green arteries coursing through brutalist settlements, women may place biophilia at the heart of 21st-century urbanism.

Concrete-built Brutalism has left its mark in our urban environments. Biophilic design as informed by women can foster healthier and more beautiful places and holds the potential to rectify the negative impacts that brutalist architecture descending from modernist planning has codified in sterile and unsociable housing schemes. By reweaving broken links, fostering local food systems, and coevolving lively green arteries coursing through brutalist settlements, women may place biophilia at the heart of 21st-century urbanism.

16 Comments

Join our conversation