About the Writer:

Carmen Bouyer

Carmen Bouyer is a French environmental artist and designer based in Paris.

Introduction

In order to keep a trace of the major collective experience we all went through during quarantine time, Anne Brochot, and myself as an invited artist at Cour Commune, launched a program called « Et Après? » (what’s next?) throughout the Summer. Cour Commune is a third place that includes a printing studio, visual art residency, and communal garden, based in an ancient 19th century shop located in Voulx, a small village 100km south of Paris.

We invited neighbours and friends to write about what they lived during quarantine, what they learned, what became obvious to them and what they wished for the future while confined in their homes. We are extending here, on The Nature of Cities platform, our collective inquiry, opening it to a larger network of artists living around the globe and focusing on the relationship to nature. We are exploring here how artists’ relationships/or non relationship with nature have moved them during lockdown. What kind of nature experience did they have during quarantine? How did it manifest itself? What teachings did those experiences convey?

To you too, who is reading these lines, we invite you to reflect on how your relationship to nature has been or is shaped by this time: what is standing out that needs to be remembered and put into practice?

About the Writer:

Anne Brochot

In 2012 Anne created CourCommune, an artistic third place located 100 km from Paris, which she animates in the spirit of Robert Filliou: "Art is what makes life more interesting than art". The way of life, around a workshop space and a garden, is participative and inspired by the regrowth movement.

Anne Brochot

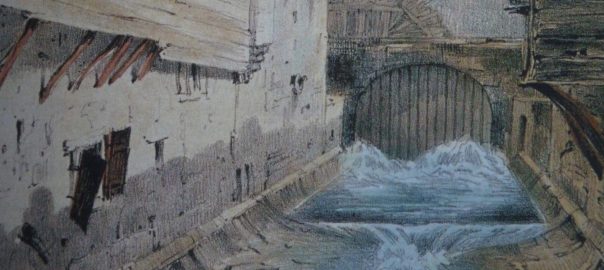

I created CourCommune in 2012 and we moved into an old village grocery store in 2016. We welcome artists in residence and organize many other events. A month before the lockdown we needed to shore up the cellar, which was threatening to collapse. We are in full lockdown, we realize that our foundation is fragile and the building could collapse. We cover the entire studio and the masons tear up the floor. I move my office upstairs, just above where they are working.

May 5th. Since 8 a.m., the jackhammer has been breaking through the concrete mass supporting a brick pillar in the cellar that has exploded under the weight of the two-storey building. Several tons rest on a few poorly mortared bricks. Suddenly, I hear a crashing, metallic noise and feel vibrations, then, silence. In the wall just behind me, a series of crystalline, musical sounds; the particles of the plaster tearing. For two seconds, the floor shifts, almost imperceptibly. A barely audible crackling sound and it’s over. Gravity has provided the structure with new-found stability.

During the few seconds it takes for the weight to transfer from one reinforcement to another, I feel the words of the psychoanalyst Jean-Pierre Lebrun “to support oneself in the void” pass through me. To support oneself in a vacuum does not mean believing in a possible vessel that carries the vacuum. No, emptiness is our condition. Yet, we need to exist and possess skills, to reflect and to concentrate during the moment when, for however long and for whatever reason, individually or collectively, we will have only the void as our only support.

FR

J’ai créé CourCommune en 2012 et nous sommes rentrés dans une ancienne épicerie de village en 2016. Nous y accueillons des artistes et bien d’autres choses. Un mois avant le confinement nous avons dû étayer une cave qui menaçait de s’effondrer. Nous sommes en plein confinement, nous constatons que nos fondations sont fragiles et le bâtiment nous parle d’effondrement. Tout l’atelier est bâché, le sol est ouvert, les maçons travaillent. J’ai monté le bureau à l’étage, je suis installée juste au dessus des maçons.

5 mai. Depuis 8h, le marteau-piqueur défonce le massif de béton supposé soutenir un pilier de briques dans la cave et le pilier lui-même. Ce dernier a explosé sous la charge de l’étage et du toit. Plusieurs tonnes reposaient sur quelques briques mal maçonnées. Puis des bruits de masse, un bruit métallique, des vibrations, et le silence. Et là dans le mur juste derrière moi, des crépitements minuscules, une série de sons cristallins, musicaux ; les particules du plâtre qui se déchirent. Pendant 2 secondes, l’étage se repose sur un appui qui descend, imperceptiblement. Un craquement à peine audible et c’est fini. Le principe de gravité a redonné à la structure une nouvelle stabilité.

Pendant les quelques secondes nécessaires au transfert d’un appui à l’autre, j’ai senti passer en moi l’expression du psychanalyste Jean-Pierre Lebrun « se soutenir dans le vide ». Se soutenir dans le vide ne veut pas dire croire en une possible propriété porteuse du vide. Non, le vide est notre condition. Mais il faut des étais, du savoir faire, de la réflexion, de la concentration autour du moment où, pendant un temps plus ou moins long et pour quelque raison que ce soit, individuellement ou collectivement, nous n’aurons que le vide pour seul appui.

About the Writer:

Elmaz Abinader

Elmaz Abinader is the author of two poetry collections, a memoir, Children of the Roojme and several plays. This House, My Bones was the Editors Selection 2014 for Willow Books, and In the Country of my Dreams won the Oakland PEN award for poetry. She is a co-founder of VONA—the workshop for writers-of-color. She lives in Oakland, CA.

Elmaz Abinader

The Collapse in the Quiet

…imagine looking down on earth, seeing marionette strings

that once kept it afloat in the black current.

Think of every moment breath swept through you,

unremarkable. Your heart squeezing a handful of red petals//…

— “After” by Ruth Awad in Set a Music to Wildfire

I had put you, the book, Almost a Life, to rest in the quiet. World struck with fever, I had to figure out how to sustain and develop the story of Dede from the shelter of my porch overlooking the looming redwoods and blossoming peach tree. There was no other way to approach the chaos of the civil war, except in the company of the fierce rotations of nature, where death brings life, and decomposition feeds new bodies. I sat in gardens filled with wild tomato vines, in giant forests where treetops fused together, on empty beaches, feet dug into sand, words resting on my knees. Dreaming in an Arabic that was colloquial, illiterate and insufficient, I finished, confidently, I thought.

But Lebanon, you did not let me go. My eye drifted from one news story to the next, to the view of Beirut: the port, the Corniche, the night clubs, the restaurants, Pigeon Rock. I stepped in the shoes of my mother and father’s promenades, my own strolls along the beach, the lingering on the rail watching the fishermen and their long rods.

And then you exploded: the first time, a tremor in the chest; the second — I rose and fell and rose again. A gasp that has not exhaled. When a city explodes, the air becomes inhabited with flying glass, the sea burns a sickening ash, the trees in Martyr’s Square collapse as if they were never rooted. When a city ignites, all is fire: the frantic rush to rescue a body, the words calling for help, the hearts who don’t imagine what can survive or how they can live. Just like that, the cells have shifted, in every living thing.

I have not let go, after all. Here I sit in California where fire is consuming the hills. Today 367 wildfires. Today, they say, prepare to evacuate. Where I wrote is off-limits; do not go outside. The city of my obsession is in shambles: Beirut is changed forever. Lebanon, we are at the beginning again: wondering how it will go, how the story will end. You reach out; I take your hand.

About the Writer:

Frances Mezzetti

Frances is a visual artist and works in live art, video and sound, with performances nationally and internationally. At present she is exploring connections through technological inter - actions in various groups. Her work is mostly collaborative, choosing to develop projects on relationships with other humans within the environment.

Frances Mezzetti

It’s Springtime. Nature is taking her time. The red poppy welcomes the bumblebee! There is a quietness, a silence in the sky, an absence of the heavy reverberation of jet engines overhead, no white tail streaks across the blue. Blackbirds, robins and twittering sparrows, thrill us with their singing. Pause in the still morning barefooted on the grass, the ground is hard for lack of rain. Feel blessed to have this space to go outside! The streets are empty. It’s the script of a movie of the end of the world. The questions is: Is it ? What have we done? What are we doing to this beautiful planet to these/us endangered species? Busyness is slowing down. Fear meets us from the TV, the pandemic, with daily statistics of contagion and deaths. This is not just a local hiccup, a town in flux, a city ground to a halt, a country watching, waiting, a continent, a globe suspended in time. While borders are closing, people are opening up to each other across fences, balconies, reaching out but not touching, sending vibrations of care like the opera singer in Milan!!

Time to reflect and to envision for the future!

A kinder, compassionate world, softer, listening to nature, to her creatures, to what matters. A world with making less the pressure as we set Zoom up and move in our respective garden or spaces and tune into each others movements through the flatness of the screen to connect and open up a space of consciousness, to imagine, to create!

About the Writer:

Jane Ingram Allen

Jane Ingram Allen creates environmental art projects around the world using natural materials and collaborative processes to raise public awareness about environmental and social issues. Allen also curates international environmental art projects and writes about sculpture and environmental art for publications such as SCULPTURE, PUBLIC ART REVIEW, and ART RADAR ASIA.

Jane Ingram Allen

During these months of isolation, I have had time to reflect and make art and also to start a vegetable garden. One art project I set for myself is to create a mixed media painting each week on handmade paper I create from plants in my own yard. I call these works “Quarantine Flowers”. I wanted to do something hopeful and uplifting, and the colorful flowers were particularly appealing. These paintings depict flowers that were blooming in my yard during the Spring months of quarantine: pink apple blossoms, blue oxalis, cream orchids, golden poppies, yellow sunflowers, and red nasturtiums.

During the quarantine I made paper “from scratch” in my garage studio using the bark of the mulberry tree in my front yard. Making paper from plant materials involves gathering the bark, cooking it, beating it to a pulp and then forming the sheets. Mulberry bark is one of the best plant fibers for papermaking; paper mulberry bark is used in Japan to make some of the finest paper in the world. My mulberry tree is not the same one that is used in Japan, but it is from the same plant family. The mulberry bark paper is thin and strong when done in my modified Asian style. This Zoom program now available online shows my process for making paper directly from plant materials.

About the Writer:

Joyce Garvey

Dr Joyce Garvey is a Scottish born visual artist and writer, living and working in Ireland. She is a graduate of the National College of Art and Design in Dublin with an ANCA and BA majoring in Fine Art and holds an MA in Film and a PhD in Creative Writing. She has written a trilogy of books on "women living in the shadow of famous men".

Joyce Garvey

One of the few positives of the COVID-19 pandemic has been lockdown’s beneficial effect on the environment.

Although climate change has temporarily slowed, because of Covid restrictions, it is still accelerating the destruction of the planet’s life support systems and the decline of species that humanity depends upon.

Since being presented with a beautifully preserved and intact dragonfly during an art residency in Courcommune, Voulx, France, my particular interest has been this wonderful insect whose symbol is change.

Therefore I was disturbed to read a UN report (March 2019) which noted a catastrophic decline in the abundance and diversity of insects, particularly the dragonfly.

Change is the key?

Every day during lockdown I walked to a local graveyard where I sat quietly and undisturbed and drew the glory of nature.

The question I asked was: Could I do anything through my art to preserve this beneficial effect that lockdown was having?

Inspired by the dragonfly, I devised a plan called:

“The Art Challenge”

Simply: I will commit to persuading a prominent local business to commission from me a piece of environmental art which I will complete without charge, in return for their public commitment to appoint an environmental officer to their business.

Through social media’s art societies, I will create a viral campaign challenge involving tens of thousands of artists in every city/town and village worldwide.

Challenges on social media, like the ice bucket challenge, promoting awareness of the disease ALS, worked incredibly well for charity. They can be equally successful for nature.

The positive publicity would raise the profile of artists, and businesses involved would save money too in sustainability.

But the greatest beneficiary would be us, and the wonderful, natural world we live in.

About the Writer:

Leslie Gauthier

Leslie Gauthier is an interdisciplinary artist based in Brooklyn, NY. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times and Paste Magazine. Leslie wrote, produced and performed in 23-Year-Old Myth as part of Theater for the New City's Dream-Up Festival. Her short film, “The Astronaut Hour”, was recognized by the International Independent Film Awards in 2019.

Leslie Gauthier

Brooklyn, Summer 2020

Every morning since April I wake up and greet the plants. We prepare each other for the day.

In June, protests streamed by the apartment nightly, and the plants grew with the movement. They stood in solidarity when the helicopters hovered, trying to intimidate.

The garden shook as I did when the mysterious professional-grade fireworks exploded in the peaceful summer sky. Are they trying to desensitize us?

We wilted in July: dried leaves, aphids, high heat / anxiety and insomnia. Remedies: hydration, potassium, Klonopin, early-morning yoga, the courage to try new spaces and the trust to grow into them. There were miracles — a cucumber on what I thought was a tomato plant. There were casualties: the cilantro, RIP.

A fighter jet flew over Brooklyn yesterday. The windows rattled, worse than the fireworks.

How can an American — an immigrant — right the wrongs done to this land? How can I make myself indiginous to a place my ancestors didn’t know? How will I survive the conflict I fear is coming? Do people garden in wars?

Manhattan’s buildings stand empty and gray across the river. My old life a backdrop to a smaller but generative one — full, colorful, and a home. My deck is an ecosystem: bumble bees and blue-winged wasps, grasshoppers, ladybugs, spiders. More, too. But I’m still learning.

About the Writer:

Munira Naqui

Munira Naqui is a visual artist who was born in Chattogram, a bustling port town on the coast of Bay of Bengal which is now Bangladesh. She now lives in Portland Maine, a beautiful coastal town at the edge of the Atlantic Ocean and works in her studio tucked in the woods across a pristine lake. Her work is abstract, concrete and reductive in nature. To her painting is a form of language that gives shape to a space for contemplative engagement.

Munira Naqui

Light, like life, can be delicate,

fragile, unique, volatile, ethereal.

But of unbearable lightness.

Let me dream reality, another reality—Fernando Pessoa

It was very quiet at the lake. Not unusual for that time of the year. Most of the cottages were closed down for the season. The lake and nature here was on its normal schedule. Nothing had changed here. I found that reassuring as I felt the human part of my world descending into chaos.

I settled down to be in the gentle rhythm of nature. Watched the signs of Spring as the snow heaps diminished and the woods slowly stirred into life with shades of green. The chartreuse of leaf buds changed into deeper forest green, the drama of the ice melt on the lake as its surface changed from white to dark patches and finally into the color of water. The birds got busy building nests, the tree frogs chirped. The sun had changed its angle and I discovered new shadows. The lake was ready for people to return but no one came. This is when I started to pine for human presence and got restless. We also realized with the way the public health crisis was handled we were in for a long haul. It made me sad to think that all my travels were cancelled. I wouldn’t be going to Cour Commune for my residency this year. Worse, I would not be able to visit my mother in Bangladesh or see my grandchildren in far away states.

We entered a phase of cloudy days with no rain. Then suddenly thunder and lightning lit up the sky accompanied by a heavy down pour. I stayed inside reading that day. At some point I looked up from my book and saw the sun come out casting a magical light on the lake. The leaves on the trees were shimmering in the golden light. It was still raining, but gently. I stepped out on the deck to capture the sight. I stood quietly in the rain watching the magic. Something lifted off my heart. I felt the lightness of being.

Smith and Kadinsky are not alone in being drawn to running water. Paul Talling’s

Smith and Kadinsky are not alone in being drawn to running water. Paul Talling’s

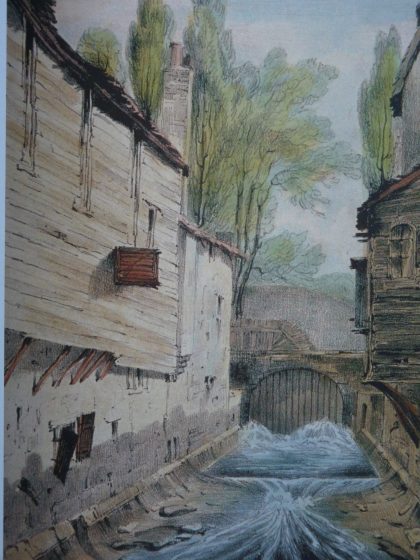

Beautifully written with a wealth of detail, The Lost Rivers of London, by Barton and Myers, provides an invaluable historical perspective on the fate of many small rivers that still flow beneath the streets of London. The course of each river has been identified from historical records, paintings, photographs and maps, including one of the earliest maps of London dated 1559.

Beautifully written with a wealth of detail, The Lost Rivers of London, by Barton and Myers, provides an invaluable historical perspective on the fate of many small rivers that still flow beneath the streets of London. The course of each river has been identified from historical records, paintings, photographs and maps, including one of the earliest maps of London dated 1559.

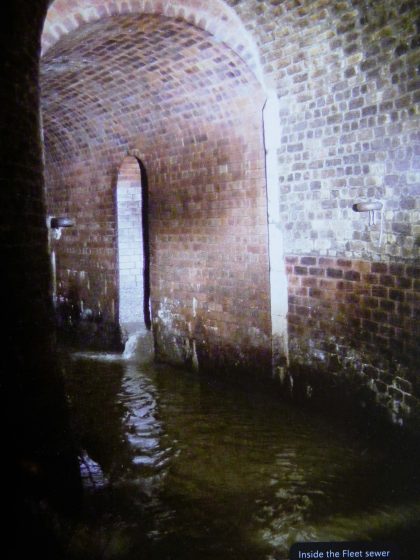

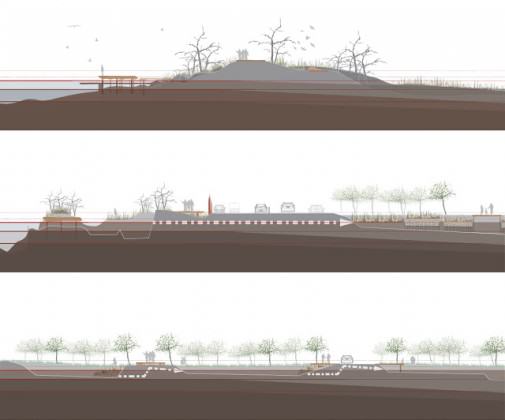

The Lost Rivers of London looks ahead and sees prospects for bringing back some of the hidden rivers. This has already been achieved for sections of small tributaries south of the Thames. Barton and Myers argue that it would be possible to do the same, even in the centre of London. The key to success of such a scheme is the fact that several of the lost rivers were naturally fed from unpolluted springs and streams on Hampstead Heath. At present this water is diverted straight into the local sewage system; a complete waste of a valuable asset. The authors suggest that this water could be channeled by gravity through a new pipeline into central London where it would certainly be possible to recreate short clean stretches on the courses of the Fleet, Tyburn, Westbourne and Walbrook in the very heart of the city. Now there’s a vision; the Fleet flowing again through the capital as a sparkling stream! This book is a must for anyone dealing with urban planning and design, not only in post-industrial cities, the lessons are just as valid in new cities today.

The Lost Rivers of London looks ahead and sees prospects for bringing back some of the hidden rivers. This has already been achieved for sections of small tributaries south of the Thames. Barton and Myers argue that it would be possible to do the same, even in the centre of London. The key to success of such a scheme is the fact that several of the lost rivers were naturally fed from unpolluted springs and streams on Hampstead Heath. At present this water is diverted straight into the local sewage system; a complete waste of a valuable asset. The authors suggest that this water could be channeled by gravity through a new pipeline into central London where it would certainly be possible to recreate short clean stretches on the courses of the Fleet, Tyburn, Westbourne and Walbrook in the very heart of the city. Now there’s a vision; the Fleet flowing again through the capital as a sparkling stream! This book is a must for anyone dealing with urban planning and design, not only in post-industrial cities, the lessons are just as valid in new cities today.

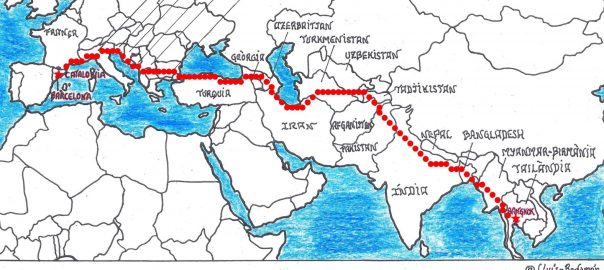

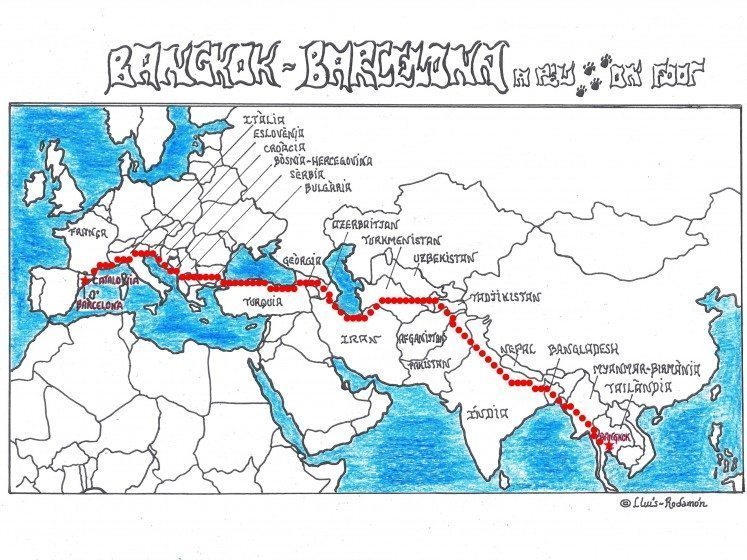

Walking. It’s a natural, human thing to do. Whether we wander through wide open green spaces or ramble around in cities, the simple act of putting one foot in front of the other makes everything around us feel more intimate. Walking puts the unreachable within reach.

Walking. It’s a natural, human thing to do. Whether we wander through wide open green spaces or ramble around in cities, the simple act of putting one foot in front of the other makes everything around us feel more intimate. Walking puts the unreachable within reach. What are we looking for? We are seeking goodness in the world. It’s our anti-fear approach to living life well. The ubiquitous headlines screaming about all the wrong being done everywhere have created a world that seemingly wants to surround itself with fear—fear of uncertainty, fear of “those people,” fear of our neighbors. We don’t buy into that. Our live-our-best-lives intuition and longtime backpacking experience tell us that there is more good in the world than bad. And we believe that if we start with the humble (or perhaps lofty) ideas that the whole world belongs to each and every one of us (not just a chosen few in wealthy, developed countries), that we all belong to each other, and that everyone deserves respect, kindness and compassion, then something that looks like goodness naturally flows.

What are we looking for? We are seeking goodness in the world. It’s our anti-fear approach to living life well. The ubiquitous headlines screaming about all the wrong being done everywhere have created a world that seemingly wants to surround itself with fear—fear of uncertainty, fear of “those people,” fear of our neighbors. We don’t buy into that. Our live-our-best-lives intuition and longtime backpacking experience tell us that there is more good in the world than bad. And we believe that if we start with the humble (or perhaps lofty) ideas that the whole world belongs to each and every one of us (not just a chosen few in wealthy, developed countries), that we all belong to each other, and that everyone deserves respect, kindness and compassion, then something that looks like goodness naturally flows. Goodness comes in an endless number of varieties. It’s that moment when a complete stranger invites you into their home and offers you tea, or walks with you to the place for which you’ve asked directions. It’s the helping hand, or the smile of understanding that breaks language barriers. It’s also birds singing in a tree-filled park where people stroll hand in hand and children play. It’s listening to waves roll in while strolling along a beachside pedestrian promenade, and watching and helping people plants seeds and harvest vegetables in community gardens. Goodness is appreciating the clean, potable water from your sink, and having a safe place to sleep every night.

Goodness comes in an endless number of varieties. It’s that moment when a complete stranger invites you into their home and offers you tea, or walks with you to the place for which you’ve asked directions. It’s the helping hand, or the smile of understanding that breaks language barriers. It’s also birds singing in a tree-filled park where people stroll hand in hand and children play. It’s listening to waves roll in while strolling along a beachside pedestrian promenade, and watching and helping people plants seeds and harvest vegetables in community gardens. Goodness is appreciating the clean, potable water from your sink, and having a safe place to sleep every night.

Where can you get more information?

Where can you get more information?

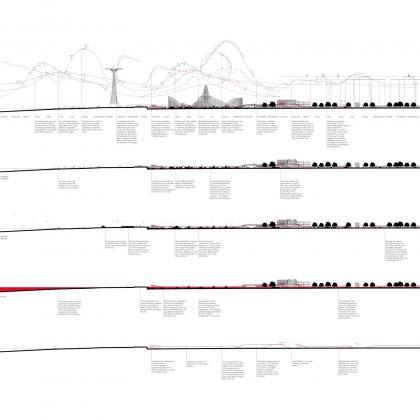

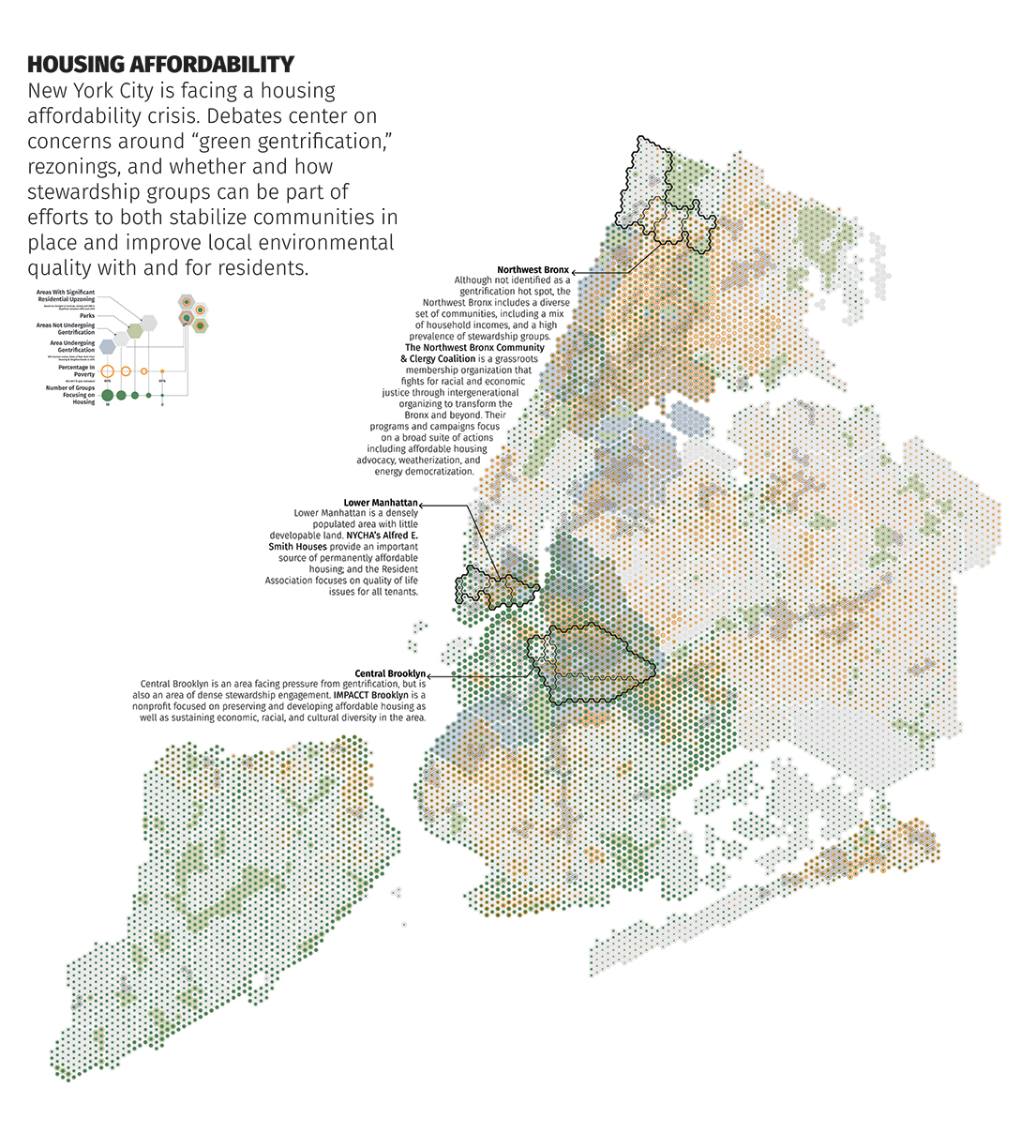

My vision for a just city is one where design and its power as a tool against inequality is leveraged for the benefit of all residents. As the director of design programs at the National Endowment for Arts, and one of the U.S. government’s primary advocates for good design, I spend a lot of time with mayors and other leaders advocating for the power of design. In the words of Charleston, South Carolina Mayor Joseph Riley, a mayor is “the chief urban designer” of his or her city. Even so, most mayors require education on what design can do—and what it cannot do.

My vision for a just city is one where design and its power as a tool against inequality is leveraged for the benefit of all residents. As the director of design programs at the National Endowment for Arts, and one of the U.S. government’s primary advocates for good design, I spend a lot of time with mayors and other leaders advocating for the power of design. In the words of Charleston, South Carolina Mayor Joseph Riley, a mayor is “the chief urban designer” of his or her city. Even so, most mayors require education on what design can do—and what it cannot do.

11 Comments

Join our conversation