“A sustainable city is one which contributes to sustainable development, and to do this it must have a high level of urbanization. (…) Without urbanization, it’s nearly impossible to have important development and growth in the economy.To have a city that generates wealth, prosperity and jobs for young people, you need to have planned organization. (….) This is the price one needs to pay so that a city, on top of being a city, is a wealth-generating engine.” —A statement of one of the main speakers in the Urban Summit, a side event at the Rio+20 Conference.

When I heard this at the Summit, I thought I had misheard or misunderstood. It was hard to swallow such a statement considering the context—a the global environmental event—and the organization the speaker represented. Unfortunately I had heard correctly, and the speaker repeated the statement, complementing it with further arguments related to economic growth, development, efficiency. The speech closed with final recommendations for the mayors present, before giving the floor to the leader of a technology firm, a sponsor of the summit.

Well, they where being consistent with Mr Ban Ki-moon’s message to the delegates attending the 23rd ESSsion of the Governing Council of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT) in Nairobi, Kenya (April 11, 2011), where he:

“…called for the use of science and technology to build better cities, saying that most global population growth in the coming years is expected to occur in urban areas of developing countries, with rising demand for land, housing, basic services and infrastructure.”

The only problem is that they forgot science. They also forgot wellbeing, equity, nature and…biodiversity.

Here, we want to suggest elements that could help widen the perspective on cities and sustainability. Based on facts and figures from Colombia, we focus on the close and unavoidable connection between ecosystems and economies, and on how cities determine and structure this relation, but not always in the best manner.

This leads to the second main focus of this essay: the importance of the urban-rural gradient, both for the economy and the ecology, including in both cases, the well-being of the living beings inside and outside the cities.

And finally, we suggest some questions we think are critical and urgent in order to address cities in this wider perspective.

Cities/economy/ecology: an unavoidable, yet uncertain relation

Not disregarding the huge importance of cities in human history and development, and of technology in urban growth, it is hard to understand how sustainability is the result of “high level of urbanization, “wealth-generation engines”, and technology (at least for me, we don’t know about you).

Without technology, no sustainability? If this is the question to answer, I have some more:

What kind of sustainability?

For whom?

What about the small cities that are not “wealth- generation engines”, and cannot afford peak technology? “Are they doomed?

What about the people and their wellbeing, what about the environment?

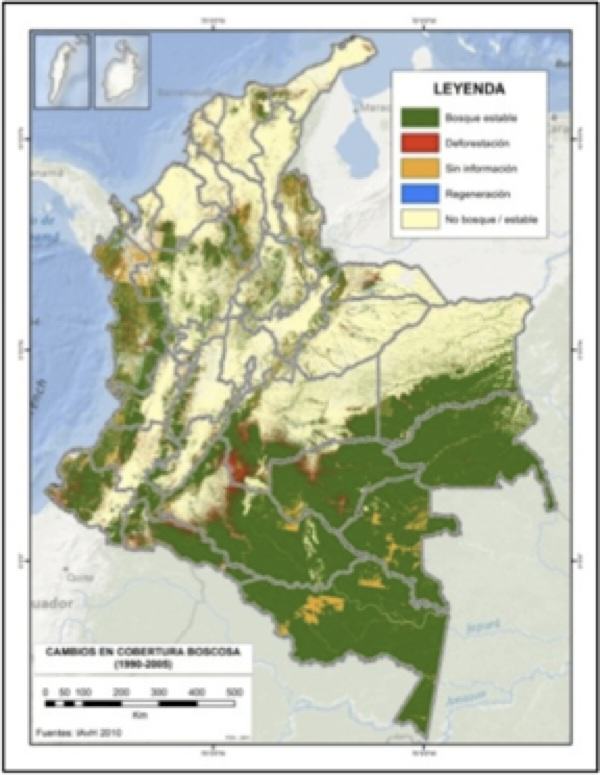

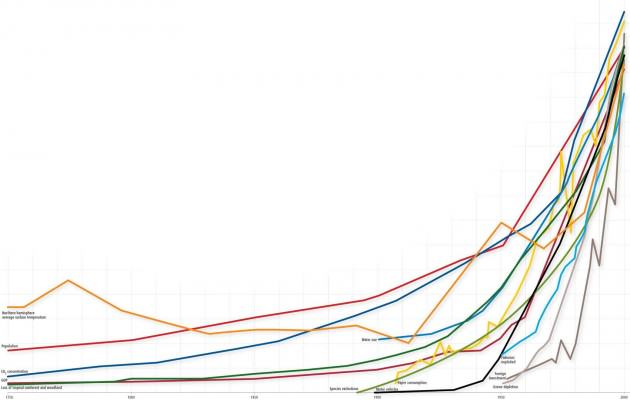

Fortunately, there are other approaches; approaches that read the figures and facts about cities and, more recently about the whole planet, in this so called “urban age”.

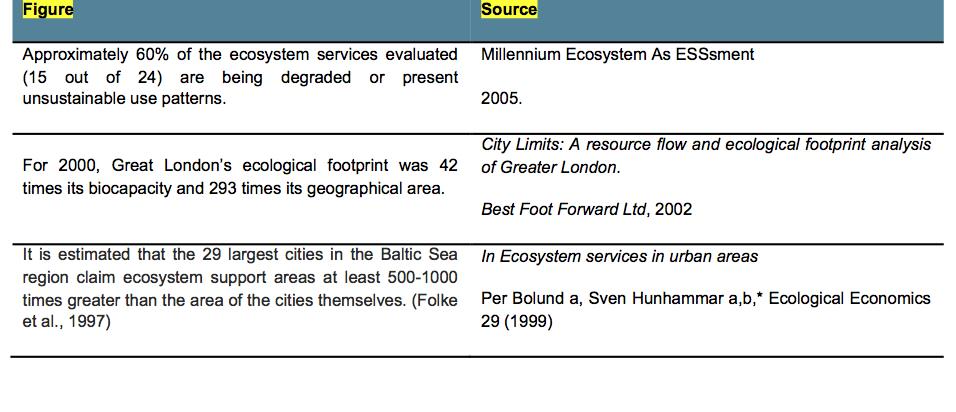

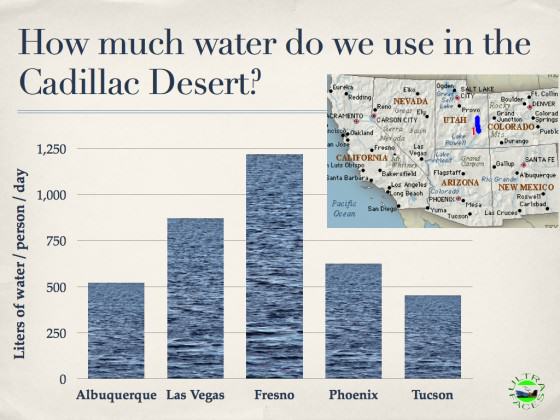

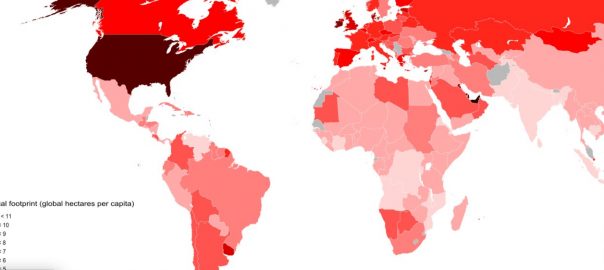

The meeting of mayors on “Cities and biodiversity” (BDC, Curitiba, Brazil, 2007) recognized that, particularly in developing countries, communities depend directly on goods and services from biodiversity (BD). Likewise, it established that the world’s cities occupy 2% of the surface of the planet, but their residents consume 75% of the total resources available. (Would they consume the same if not in the city? I guess not, cities are the “engines of consumption”) This unprecedented pressure on the BD has serious consequences for the supply of ecosystem services, climate dynamics and the well-being of the populations. Plenty of figures and facts.

Colombia, an “underdeveloped emerging” country, shares this statistic. It is estimated that by 2020, 80% of Colombia’s population, to be around 48 million at that moment, will live in urban centers, which in our case occupy about 2.5% of the national territory.

Colombia, an “underdeveloped emerging” country, shares this statistic. It is estimated that by 2020, 80% of Colombia’s population, to be around 48 million at that moment, will live in urban centers, which in our case occupy about 2.5% of the national territory.

According to the statistics, Colombia could be considered an “urban country”, as many have already assured in their political speeches, mainly former city mayors running for president. (What about the other 98% of our country?)

But, are we really an “urban country? What does it really mean that we share statistics with the rest of the world? Probably, that statistics are tricky and can be misleading, if not understood in specific, yet wider, contexts.

Cities, between green and gray

The current development model encourages the location of higher productivity activities in urban areas all over the world.

In Colombia, the city network contributes 80% of national GDP (DNP 2011). Thus, the political, economic and social attributes of urban areas in terms of access to markets and social mobility expectations have steadily captured the interest of governments, creating a “attractiveness effect” on the inhabitants of the marginalized rural areas. attractiveness with perverse effects on both cities and fields, frequently regarded just as cities hinterland, without identity.

In this context, “environment” and “sustainability” are approached, addressed and managed in different and generally not complementary ways in rural territories (natural area protection and sustainability of agriculture and forestry) and in cities (mitigation of direct impacts on water, air and soil to ensure the quality of viad of “urbanites”). Strong conceptual and political boundaries between “urban areas” and the rest of the territory have disconnected the existing relationships, specially the ecological functionality.

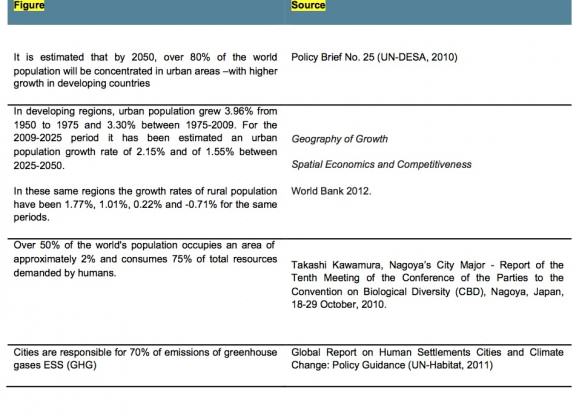

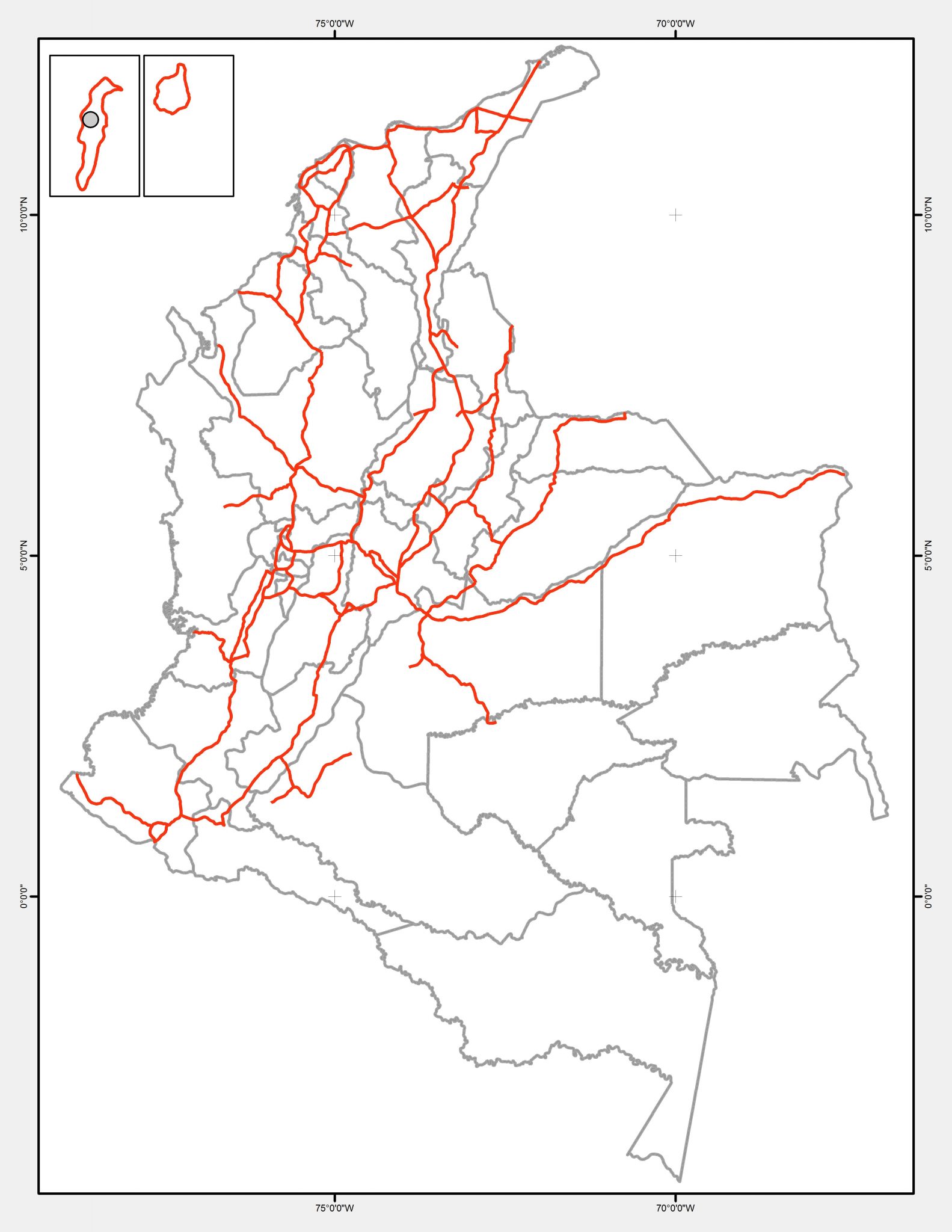

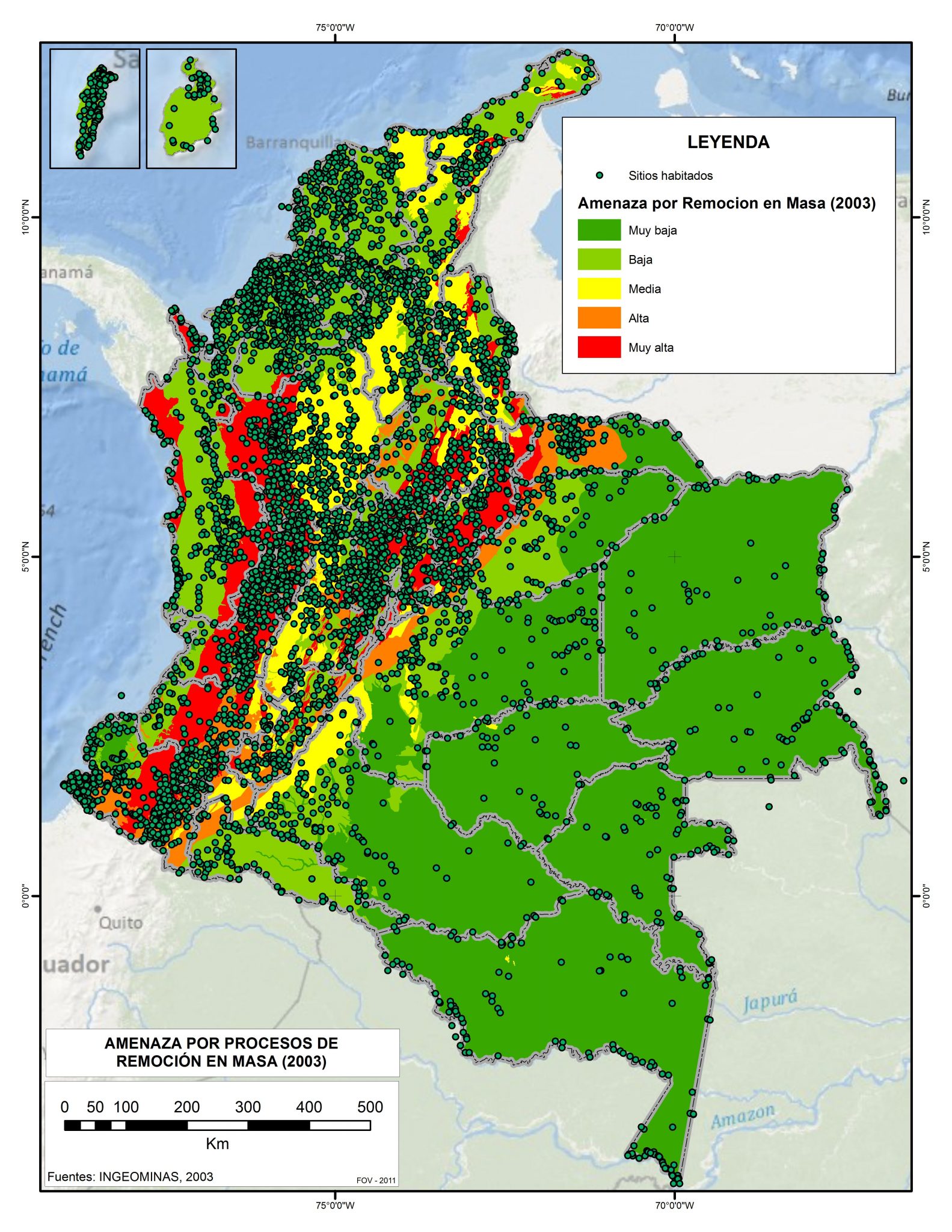

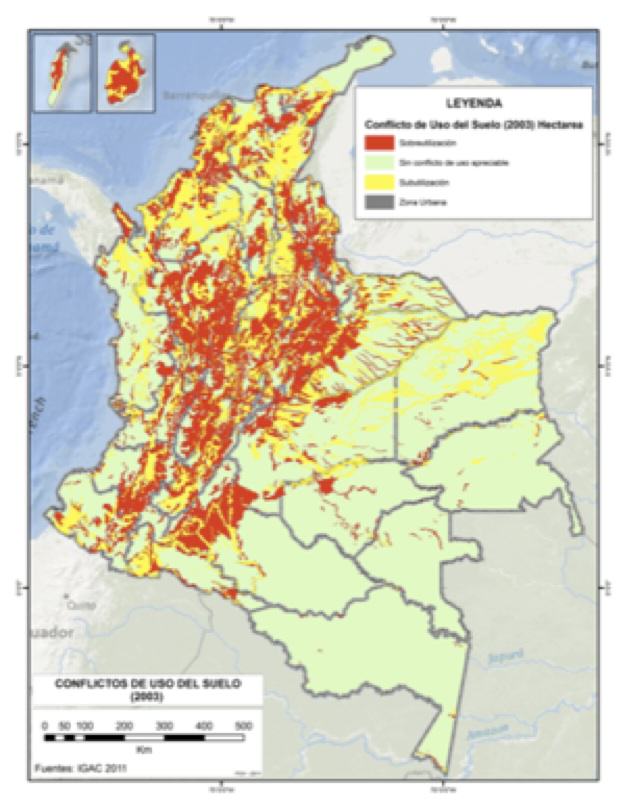

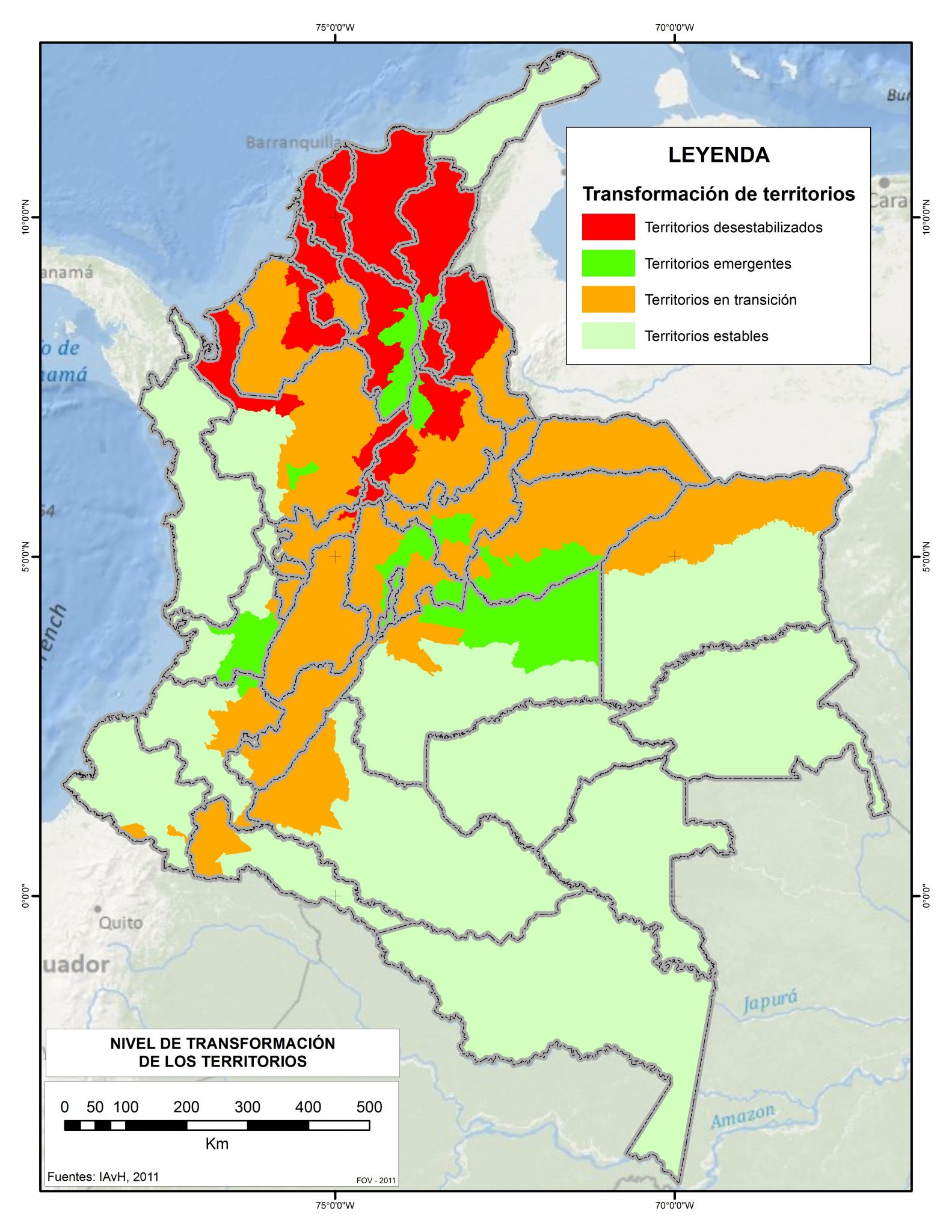

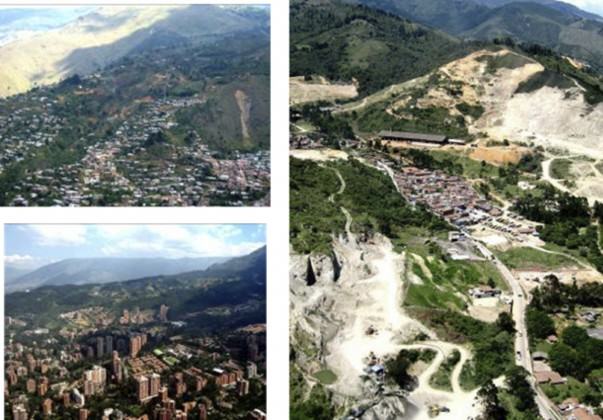

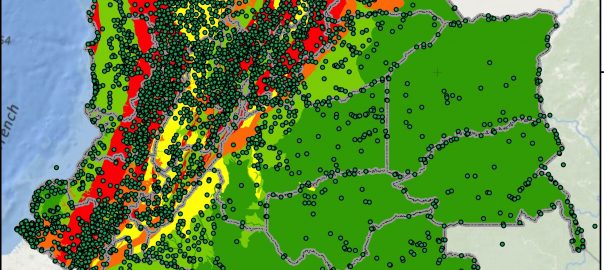

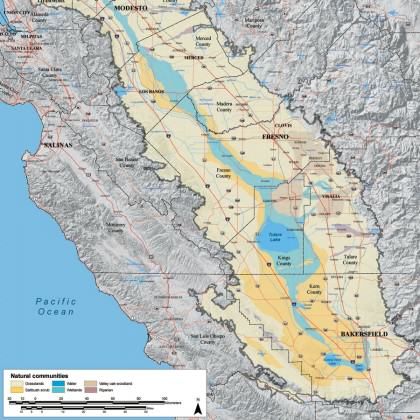

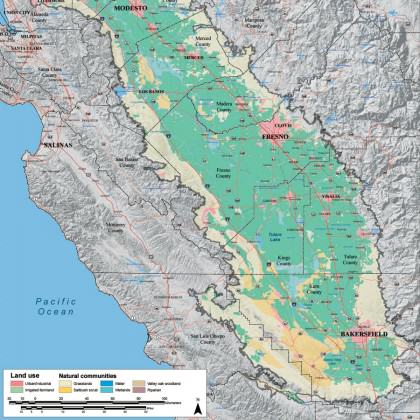

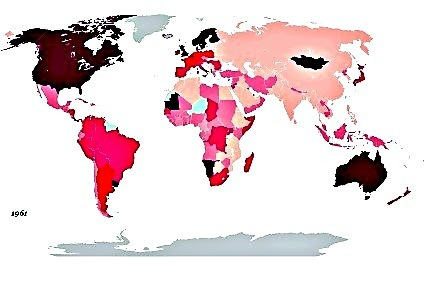

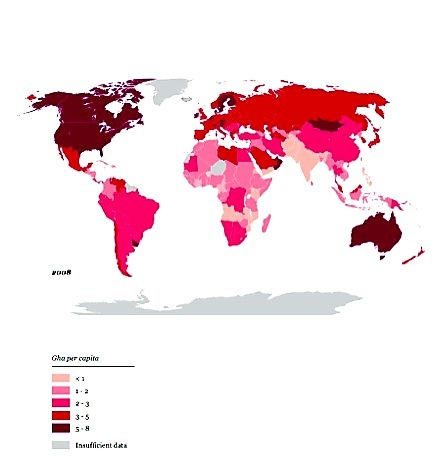

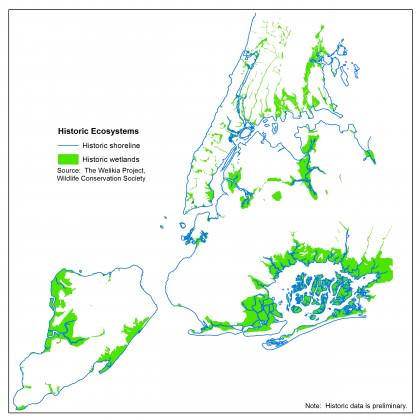

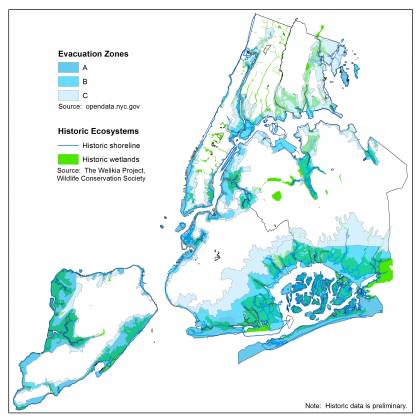

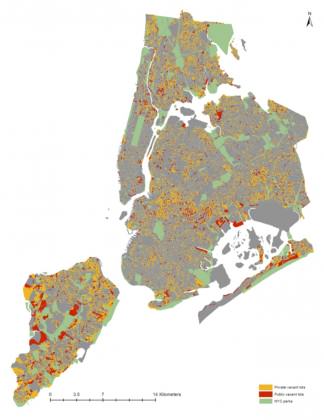

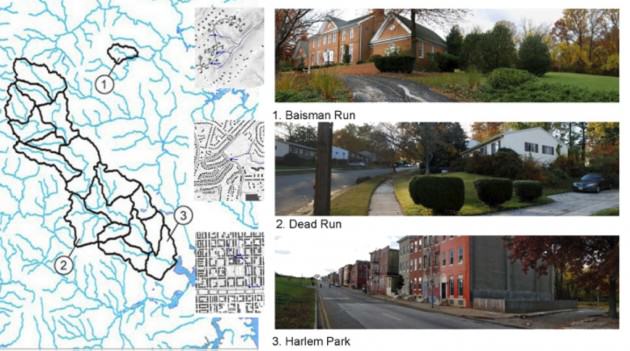

As can be seen in the maps bellow, Colombian system of cities is basically located on the Andean and Caribbean regions. The National Policy diagnosis found that biodiversity loss rates in our country were dramatically evident. National studies have estimated that Caribbean ecosystems have been transformed by 72.4% and Andean ecosystems by 62.1% on average (NPCMBES 67). From 2005 to 2010, the Andean Region presented the highest national deforestation rate at 37% (87.090 Ha/year) followed by the Amazon at 33% (79.797 Ha/year). Thereby ecosystem fragmentation and expansion of the agricultural frontier, two of the main biodiversity loss cau ESS, are mostly due to urbanization expansion phenomena.

Source: Instituto Humboldt, 2011

Population concentration and crucial economic development processes (ESS) have taken place mostly in the Caribbean and Andean regions. Since 1950, national urbanization rates have growth exponentially. In 1951, 814 municipalities revealed a 38.9% rate of urbanization; in 2005, 1119 municipalities had a 74.4% rate of urbanization (National Statistics Department—DANE, per its acronym in Spanish).

The territorial changes that most affect the BD and ESS are directly related to urban expansion and its ecological footprint. Increased suburbanization around the cities, continued development of energy infrastructure, and the extension of infrastructure networks for interconnectivity are the main culprits.

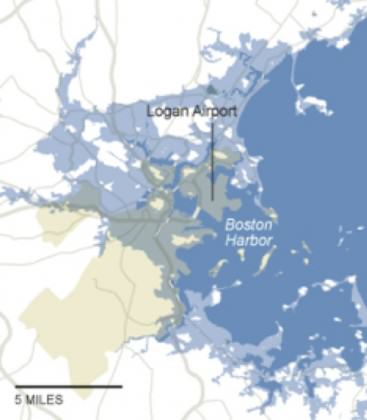

Due to the poor management of the basins and the deforestation of the Andean region, these areas are now more vulnerable. The situation is reflected in the direct relationship between the threat of floods and the threat of landslides. Here, the overlap between the city system maps and the risk maps demonstrate that land use conflict and deforestation make evident that the probability of disaster is higher in Colombian cities and their capacity for resilience is lower.

This fractional approach to social and environmental flows and trades is inequitable, unsustainable and politically obsolete. On the one hand, people who live in areas that support the demands and impacts of urban centers have significantly lower welfare conditions than urban dwellers. On the other, cities struggle to ensure good environmental conditions to a growing population. But, good environmental conditions “inside” the city don´t necessarily mean sustainability of the city. The unresolved stress between cities and not-urban territories has huge impacts in terms of loss and deterioration of BD and ESS, specially in countries like Colombia, where cities are located in rich but fragile ecosystems,

Beyond political and administrative boundaries, the impact of the city is not fully contained in the area that it occupies, but by the area that it needs to satisfy its demands.

The country has made conceptual and institutional efforts to achieve greater environmental quality in cities. However, the level of environmental degradation in the cities, the poorly structured relationship between urban and rural landscapes, and the widespread loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services clearly show that these efforts have not been sufficient and highlight the need to oxygenate the discussion and formulate new and innovative proposals, ones that recognize what is really at stake when talking about “cities and sustainability”.

Rural urban environments? Emerging ecosystems?

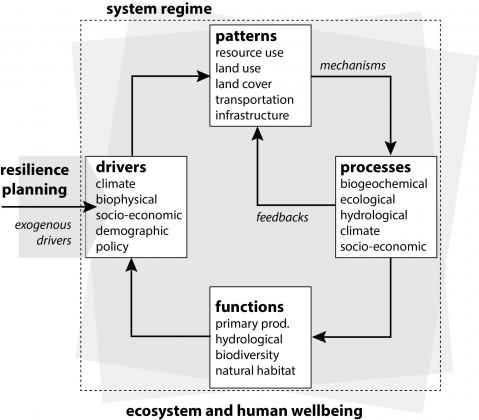

The Convention on Biodiversity, the multilateral treaty that tends actions for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from their use, defines biodiversity as “the variability among living organisms from all sources including, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems”. As active member of the Convention, Colombia adopted a national policy for integrated management of biodiversity and ecosystem services. It is based on the recognition that “[B]iodiversity constitutes an important attribute of integrated ecological and social systems, in which the relationship between man and nature is manifested not only as the alteration of a natural system (conventional vision of conservation biology), but as a new system with emergent properties of self-organization, in which the constituent variables are no longer just “biophysical” or “social” but the result of interactions between these”.

Both in natural and emerging ecosystems, ecosystem services are the explicit link between biodiversity and human welfare, thus leading to a new and specific definition of sustainability: the ability to generate a steady and adequate supply of biodiversity and ecosystem services required for human welfare.

It is clear, therefore, that biodiversity and ecosystem services must be managed within the interactions between man and nature, this is, in socio-ecosystems.

This is where the debate on the interactions between man and nature is urgent. What new conceptual and methodological approaches are required to manage BD and the ESS in landscapes deeply transformed by land use change, waste management, emissions of greenhouse gases, infrastructure, among others? Cities and their areas of influence become the unit of analysis, “mandatory” for policy formulation that fosters sustainable development. New figures and facts become relevant, as below.

We must generate and consolidate in the society a new approach to the management of biodiversity and ESS in rural urban environments. This requires not only changing the paradigms of “environmental management” but also of planning, design and urban culture. It requires that we:

We must generate and consolidate in the society a new approach to the management of biodiversity and ESS in rural urban environments. This requires not only changing the paradigms of “environmental management” but also of planning, design and urban culture. It requires that we:

(1) rethink the questions from sustainability, uncertainty and dynamism of the (socio) urban-regional ecosystems;

(2) incorporate questions about terms of resilience and adaptability; and

(3) be open in the public policy field and civic culture to new patterns of knowledge and information.

The challenge is not based solely on the current and future demographic pressures. UN-HABITAT has estimated that the population of 46 countries—among which are Germany, Japan and Italy—will decrease by 2050 (Oliveira 2011). The reason for reviewing planning models is that the current models of BD and ESS treat biological, ecological and social systems differently, mainly due to new types of landscapes that don´t conform to the traditional definitions of “urban” and “rural”. Suburban, peri-urban, boundaries, and neo-rural are examples of new names that try to define new (emerging) ecosystems, not yet fully understood and, therefore poorly managed. Trying to consider them as subcategories from urban or rural lanscapes has narrowed the perspective and postponed a needed discussion.

While the impact of nature on the people of cities is of high significance (ecosystem services or natural disasters, for example), these interactions and flows have been weakly understood and inadequately included in regional urban planning (Forman 2011). On the other hand, the effects of the inhabitants on the nature lack a spatial understanding (or scale) and proper time, and therefore, its management is territorially limited because ecosystems are not recognized as places “open”, in terms of the ecosystem approach implemented by the CBD in 2004.

The urban-rural dialogue must be rebuilt in this new context. This relationship seeks to promote solutions through land planning and environmental governance strategies; local, regional and national agents must be informed about the potential implications of land transformation on biodiversity loss and thus, on human welfare (Andrade, GI; Sandino, JC; Aldana, J. 2011). In this regard, interdisciplinary research (among scientific centers) and science-policy research initiatives are essential to identify policy recommendations of sustainability “in” cities and “of” cities (Grimm et al. 2000; Wu 2008a in Breuste et al. 2011).

Finally, biodiversity and ecosystem services management implies the need to rethink which kind of information and knowledge is “relevant” to guarantee this urban-rural approach and coherence. Is it local, regional, or national?).

The comprehensive management on biodiversity and ecosystem services states considers the roll of scientific and academic information beyond its production and dissemination. Information and knowledge must be aligned to specific decision-making processes under systems of cooperation among stakeholders and across levels: inter-sectorial, interagency and social (CBD 2004).

Towards the right questions

Without disregarding the important conceptual, empirical and political efforts to address the relationship between biodiversity, ecosystem services and urban dynamics, instrumental developments and theoretical approaches to respond to changes in the socio-ecological urban systems do not yet appear to be evident in relation to decision-making processes and social appropriation interests.

For this purpose, it is necessary to advance in three complementary fields or components:

(1) the integral management of information and knowledge;

(2) policy management, administrative and institutional; and

(3) the management of information and communication.

“Ecosystems” and “cities” are not separate, independent entities, as has been traditionally considered. While the first are object of “conservation strategies” (mainly related to protected and untouchable areas), the second one focuses on “environmental quality” strategies (water, air and sewage treatment, public green areas).

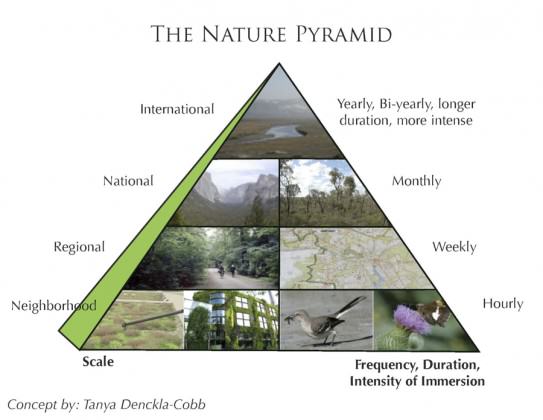

In order to manage cities as ecosystems, first we must recognize that understanding the relationship between BD, ESS and urban-regional environments is essential to generating sustainable conditions. Second, we must recognize that this relationship has diverse manifestations depending on the scale of approach: (i) the network of cities and their impact on BD and the ESS of the country; (ii) the emerging urban-rural regions and their relationships of dependence (ecological footprint); and (iii) the urban area itself and its quality of life.

Taking into consideration the implications of management biodiversity and ecosystem services across urban-regional environments, we would identify the following preliminary questions:

- To ensure their own persistence and welfare of human populations in specific territories, in a context of drastic change, what decisions should be taken by urban institutions in terms of BD and ESS management?

- What socio-ecological criteria and priorities for action should guide public policy and its relation to sectorial and land actors in urban-rural landscapes?

- How do we incorporate uncertainty, adaptability and resilience into planning and ecosystem management strategies among very different and changing territories?

- What is the capacity for innovation and adaptation of institutions, stakeholders and communities?

- How much information and knowledge do we already have to answer the above questions and to predict ESS tendencies?

- How much do we really need to talk, cooperate and act?

These questions are motivating us to apply a multi-scalar approach to urban research initiatives, acknowledging the evident (but mostly forgotten) relationship between sustainability “within” cities and sustainability “of” cities, which we will discuss in future posts.

Juana Mariño Drews

with the collaboration of María Angélica Mejía

Bogotá, Colombia

Kiwi’s (people from New Zealand — named after the iconic flightless bird) are renowned for their “will do” attitude of rolling up their shirt sleeves and getting stuck in. This project is no exception. Way back, and in amongst all the destruction and rubble and not long after the first earthquakes happened, a group of volunteers decided to bring nature back, albeit temporarily. “

Kiwi’s (people from New Zealand — named after the iconic flightless bird) are renowned for their “will do” attitude of rolling up their shirt sleeves and getting stuck in. This project is no exception. Way back, and in amongst all the destruction and rubble and not long after the first earthquakes happened, a group of volunteers decided to bring nature back, albeit temporarily. “

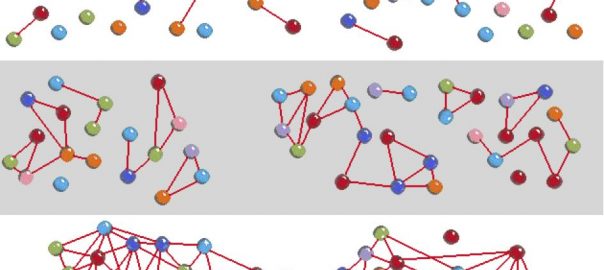

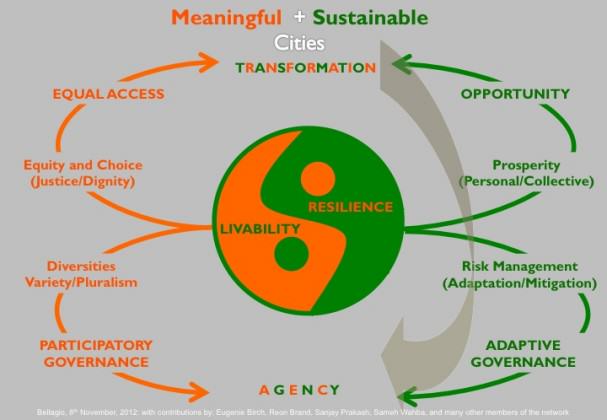

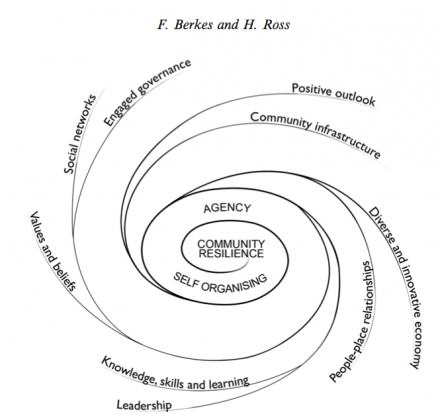

As suggested above, the capacity for self-organization is a critical attribute of city life. If it’s compromised, so is the healthy functioning of the city. Self-organization occurs at every level of city life: within households, city blocks, neighborhoods, districts, the city and region. Walking groups, street vendors, business improvement groups, neighborhood watch initiatives, buying clubs, co-locations for the self-employed, street fairs, affinity groups of all kinds: the desire for city dwellers to make connections with others is what ensures a city is productive and vital: livable. Cities are not an artificial construct (at least the most successful ones aren’t). They are creatures of the living: created by people seeking to organize their lives in ways that sustain and nurture. The dynamism that self-organization delivers, is what we call livability.

As suggested above, the capacity for self-organization is a critical attribute of city life. If it’s compromised, so is the healthy functioning of the city. Self-organization occurs at every level of city life: within households, city blocks, neighborhoods, districts, the city and region. Walking groups, street vendors, business improvement groups, neighborhood watch initiatives, buying clubs, co-locations for the self-employed, street fairs, affinity groups of all kinds: the desire for city dwellers to make connections with others is what ensures a city is productive and vital: livable. Cities are not an artificial construct (at least the most successful ones aren’t). They are creatures of the living: created by people seeking to organize their lives in ways that sustain and nurture. The dynamism that self-organization delivers, is what we call livability.

In contrast,

In contrast,

Most intriguing to me was the on-line community that formed around these birds. During the second season of Raptor Cam, the number of hits on the site jumped to 400,000 and by the third season, hits approached 1 million. Dozens of people wrote in daily with their thoughts, opinions, questions and hopes for these birds.

Most intriguing to me was the on-line community that formed around these birds. During the second season of Raptor Cam, the number of hits on the site jumped to 400,000 and by the third season, hits approached 1 million. Dozens of people wrote in daily with their thoughts, opinions, questions and hopes for these birds.  As a conservation advocate and educator, what I found particularly gratifying was the number of people we were able to reach who otherwise might never have noticed a bird in the city, people who otherwise might be out of reach to a conservation organization like Audubon, the holy grail of conservation education–the non-converted. It was clear from the questions and comments that for many of the most avid viewers, birds in the city, and perhaps

As a conservation advocate and educator, what I found particularly gratifying was the number of people we were able to reach who otherwise might never have noticed a bird in the city, people who otherwise might be out of reach to a conservation organization like Audubon, the holy grail of conservation education–the non-converted. It was clear from the questions and comments that for many of the most avid viewers, birds in the city, and perhaps

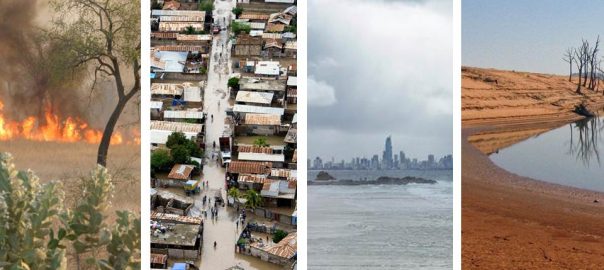

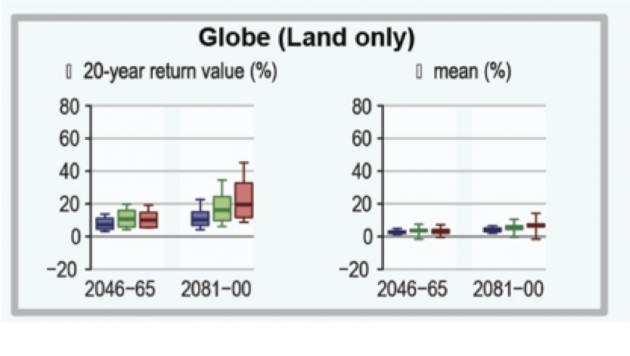

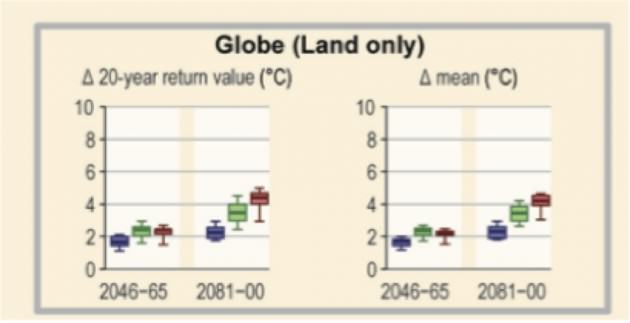

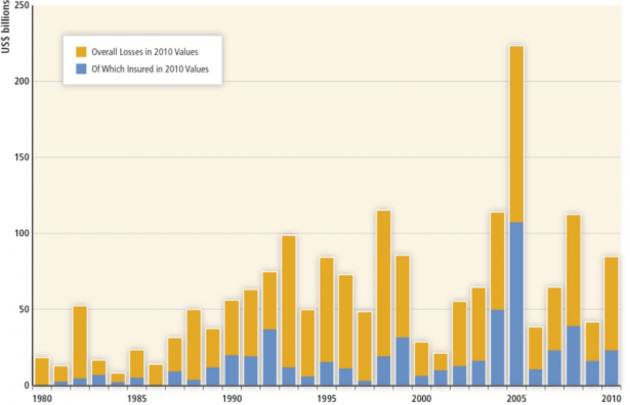

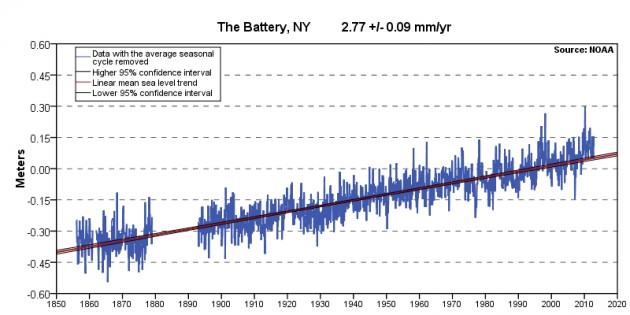

For a recent IPCC special report, ‘

For a recent IPCC special report, ‘

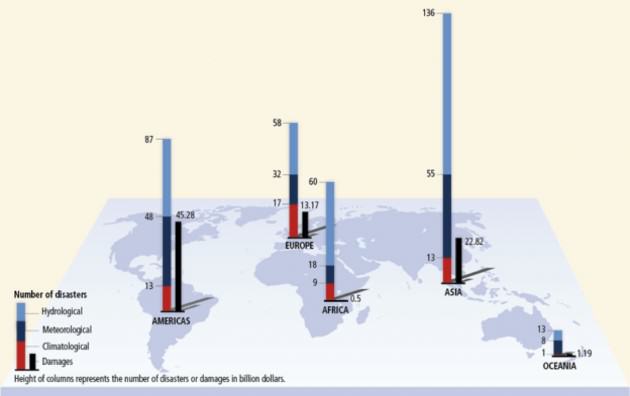

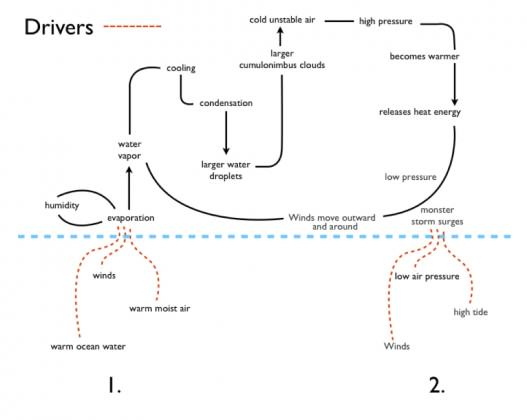

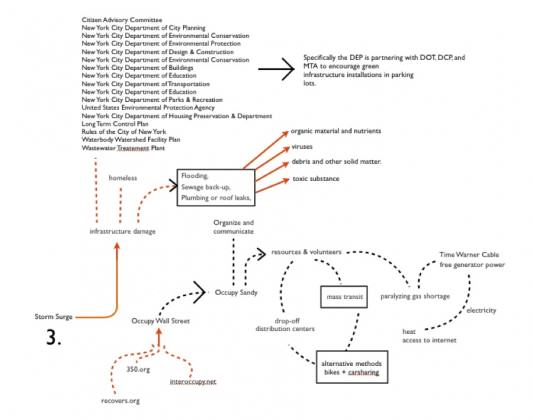

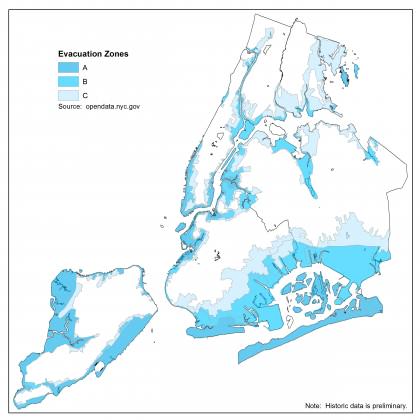

When multiple phenomena with uncertain trajectories—for example, storm surges and power outages—affect the function of cities simultaneously, the element of surprise can be enormous. Suddenly, resources and activities that everyone takes for granted, such as mobility or an energy supply, are unavailable,

When multiple phenomena with uncertain trajectories—for example, storm surges and power outages—affect the function of cities simultaneously, the element of surprise can be enormous. Suddenly, resources and activities that everyone takes for granted, such as mobility or an energy supply, are unavailable,

While a biodiversity practitioner’s effect is limited to some extent by their position, a politician is constrained more by their need to address a number of often-conflicting issues, and to satisfy their constituency. This also has quite a lot to do with personality but it’s more about awareness and subsequent willingness. If politicians have the will to support biodiversity, biodiversity practitioners are likely to be given considerable freedom in their work and, just as importantly, more likely to be able to access municipal funding. On the other hand if a politician has taken a stance in opposition to biodiversity, for example if they consider it to do nothing but impede development, then very little will be achieved by even a well-staffed and well-integrated biodiversity unit. Even the neutral politician can be restrictive because, when biodiversity comes up against other priorities, the likelihood is that this decision-maker will know and care more about a new road or housing development than about a concept with which they are less familiar.

While a biodiversity practitioner’s effect is limited to some extent by their position, a politician is constrained more by their need to address a number of often-conflicting issues, and to satisfy their constituency. This also has quite a lot to do with personality but it’s more about awareness and subsequent willingness. If politicians have the will to support biodiversity, biodiversity practitioners are likely to be given considerable freedom in their work and, just as importantly, more likely to be able to access municipal funding. On the other hand if a politician has taken a stance in opposition to biodiversity, for example if they consider it to do nothing but impede development, then very little will be achieved by even a well-staffed and well-integrated biodiversity unit. Even the neutral politician can be restrictive because, when biodiversity comes up against other priorities, the likelihood is that this decision-maker will know and care more about a new road or housing development than about a concept with which they are less familiar. The problem with both personalities and politicians is impermanence. While both represent very worthwhile mechanisms for maintaining a focus on biodiversity considerations, they do unfortunately come and go. This is especially true for the latter and necessitates a constant process of relationship-building which can be especially tricky when a new administration abhors the old, and may even get rid of officials associated with it. As an additional and supporting measure policy is, therefore, critical. It, too, can be changed over time depending on the administration but can provide an additional safeguard. Even if a new administration is bent on changing or removing it, the due process required may at least buy some time to win them over.

The problem with both personalities and politicians is impermanence. While both represent very worthwhile mechanisms for maintaining a focus on biodiversity considerations, they do unfortunately come and go. This is especially true for the latter and necessitates a constant process of relationship-building which can be especially tricky when a new administration abhors the old, and may even get rid of officials associated with it. As an additional and supporting measure policy is, therefore, critical. It, too, can be changed over time depending on the administration but can provide an additional safeguard. Even if a new administration is bent on changing or removing it, the due process required may at least buy some time to win them over.

1 Comment

Join our conversation