In 1990 the municipal landfill of the City of Elizabeth, New Jersey (near New York City) was officially closed and a leachate system, layers of cleaner soils, and two brand new wetlands were constructed. The landfill, located on the waterfront on Newark Bay, on top of the mouth of a creek that once supported the salt marsh of the Hackensack Meadows, is now covered with a self-seeded poplar forest and traversed by fishermen seeking solitude at the shore. In 2004 we (Till Design) were commissioned to co-design on this land a new neighborhood for Elizabeth, one that connected people to the key and organizing cycles of nature, and whose rhythms were explicit in the everyday life of the new residents. This neighborhood is called Celadon.

Ecosystem modeling uses patterns of past behavior to predict future trends. However, such models have difficulty accounting for humans as creative actors that learn, evolve new patterns and do unexpected things. Ecosystem change can emerge from invention, from an imagination of a better future and not only as a response to a crisis or disturbance. Are background assumptions and fundamental equations of models about the negative impacts of cities masking the complexity that people in cities generate and demonstrate, and obscuring the benefits of new design ideas?

This blog post describes the urban design model of an environmentally activist real estate development that aims to honor and use the creativity that results when people are exposed to new opportunities and patterns. Future growth based on such dynamic foundations will lead to social sustainability and ecosystem resilience for Newark Bay.

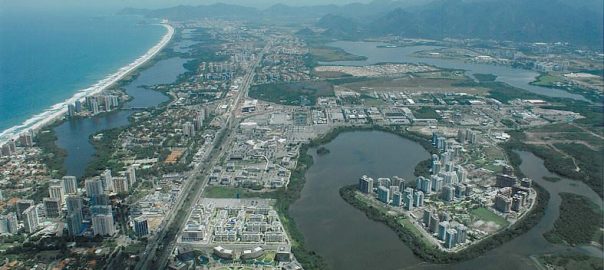

After 9/11 a ferry landing was hurriedly approved in order to provide another means of egress from Manhattan, however it was never used. In the mid 2000s, with the unused ferry permit due to expire, a discussion began around a concept of doing a real estate project on the landfill. Celadon, is an 8.75 million square foot, twenty-four hour mixed use transit village and airport city, with three thousand housing units, four public gardens, two overlook decks, two neighborhood plazas, an upper and lower waterfront promenade, a pier, ferry terminal and a ferry. The scale of the development made feasible the realization of New Jersey Transit’s long planned light rail line connecting the City of Elizabeth to a ferry terminal at the Celadon site and Newark Liberty International Airport beyond.

People infrastructure

New Jersey is not just the most wealthy and densest state in the United States, but one of the most diverse, being the point of arrival of America’s newest immigrant groups. These new residents are not like 19th century immigrants who leave their homelands behind. They are more likely to be transnational, moving between two homelands and racking up frequent flier miles. The City of Elizabeth is the fourth largest city in New Jersey and its people represent more than 50 countries and 37 language groups. Celadon is designed as a multi-level, high-density neighborhood for these new and existing immigrants and residents.

Our question was how to connect this mobile and diverse social system with a degraded and dramatic bay ecosystem?

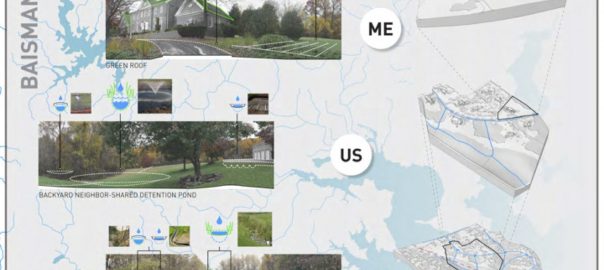

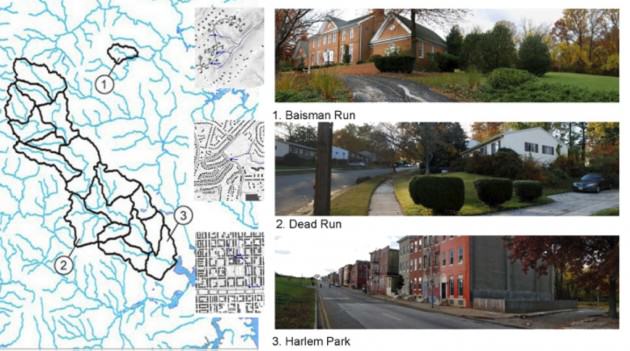

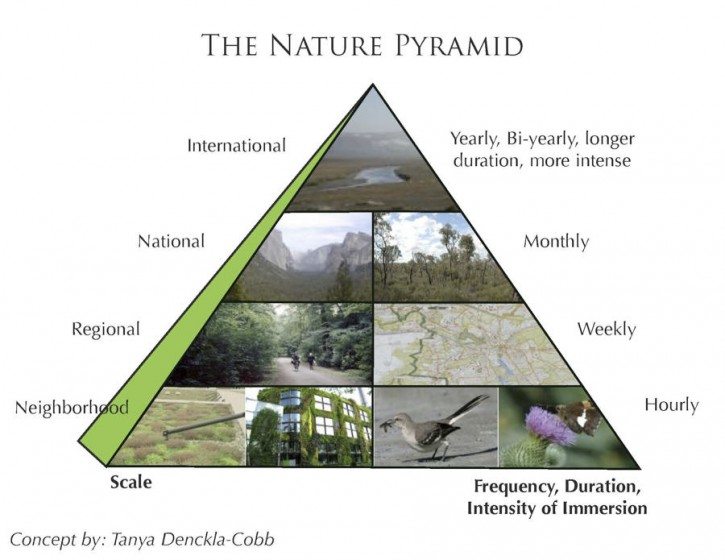

We began by offering insights learnt from the Baltimore Ecosystem Study, which revealed that the construction and use of green infrastructure such as greenway trails can be an important tool for building awareness and support for watershed conservation and restoration, and that humans can function as a regulatory feedback mechanism in the ecosystem much as a complex web of interactions maintains stability (resistance and resilience) in unmanaged forest ecosystems (Morgan Grove of the USDA Forest Service). According to Grove, social meanings, social capital and social levels of organization are linked by the fact that different social meanings and types of social capital are significant at different levels of social organization and the social ecological resilience of urban ecosystems is likely to increase with linkages among scales.

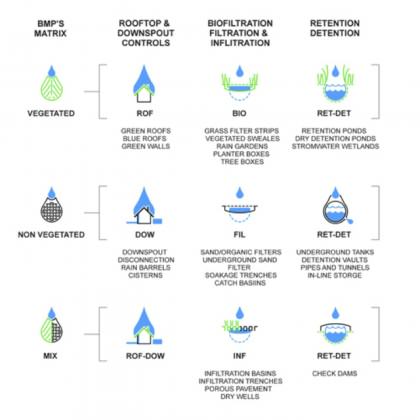

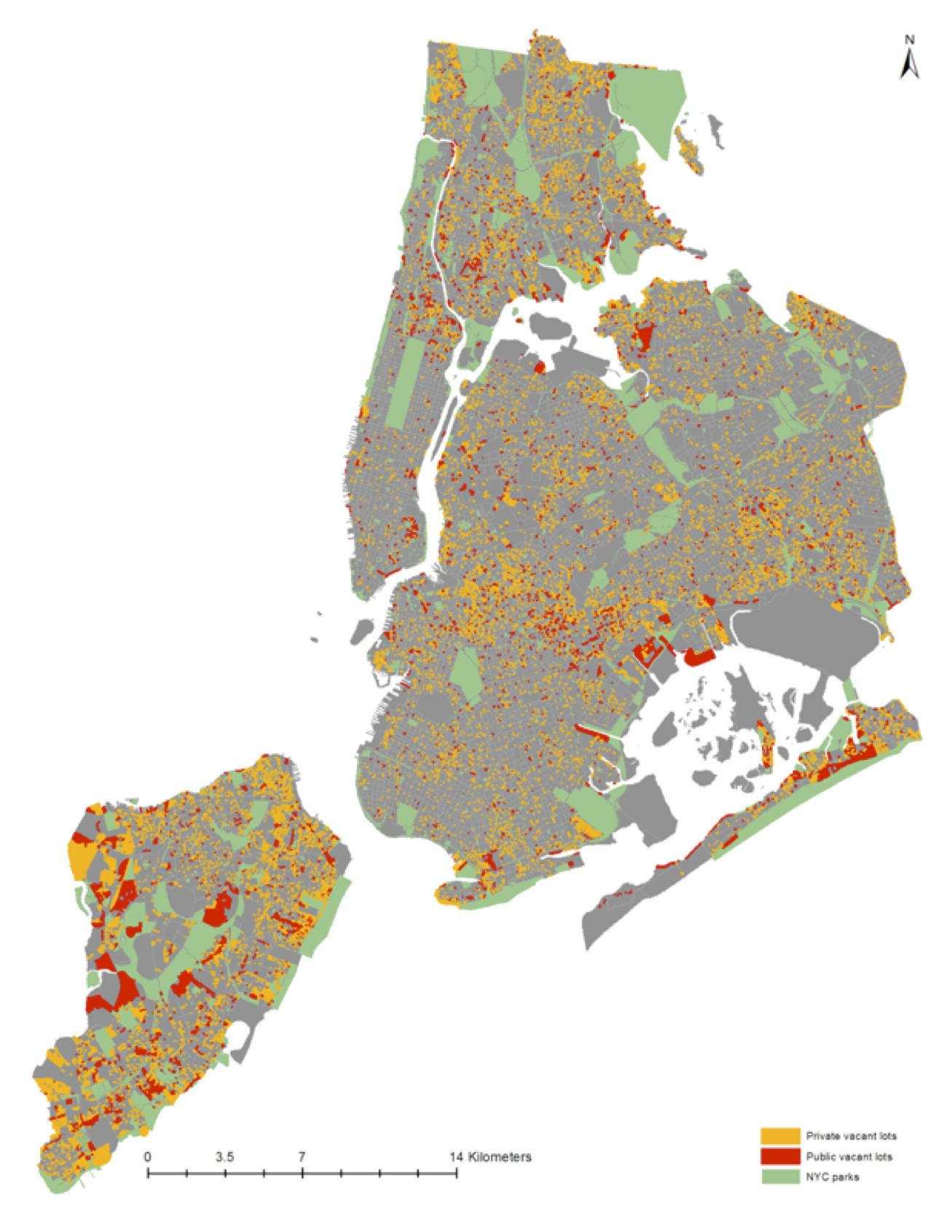

The public space and landscape design strategy discussed and presented to the development team and city officials was described as comprised of feedback loops with social and ecological complexity. Due to its industrial legacies and pattern of large fenced land parcels, Newark Bay is off limits both physically and in the general mental map of most New York and New Jersey residents when they consider recreational opportunities.

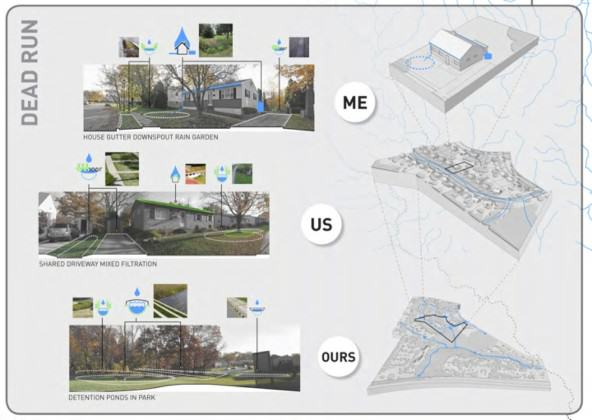

Rather than wait 12 years until all phases of the Celadon project were completed, we proposed a complementary set of temporary urban interventions that expand and complement the existing uses observed on the site, such as fishing, camping and birding. We also wanted to spiral out from the existing social networks, no matter how diffuse, starting now.

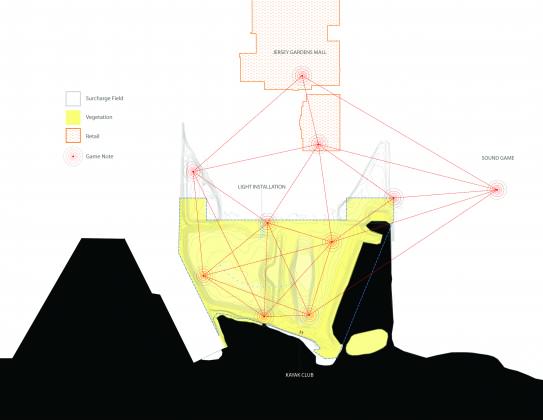

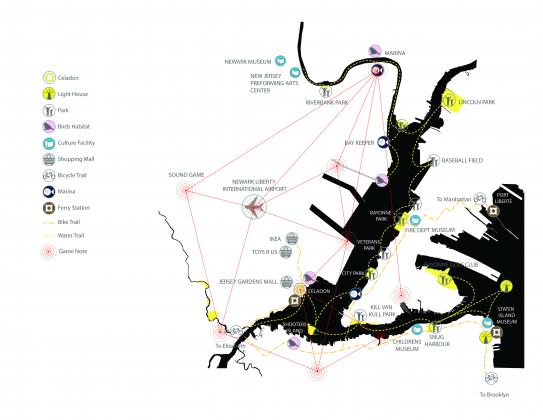

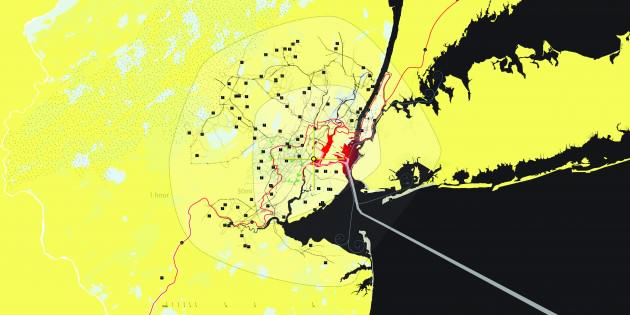

The three proposed phases of the urban interventions are: a geo-located sound game that functions like a treasure hunt. Building on the experience trend, it acts to prompt Jersey Gardens mall visitors to wander outside and explore with curiosity the huge parking lot surface of the mall, the Celadon landfill and the adjacent poplar forest, guided by a smart phone. At night the sound game nodes illuminate the ground allowing the asphalted, soily and gravelly game surfaces to be seen from the planes taking off and landing nearby. The second phase coincides with the opening of the ferry pier, concession cafe and commuter parking lot. A bike share with clip-on shopping carts and a new bike trail connects the Celadon site with IKEA using an existing maintenance trail in the poplar forest. A simple kayak clubhouse and removable launch ramp opens the shallows adjacent to the shore for recreational kayaking and gaming. A third phase coincides with the completion of the Celadon roads, buildings, designed landscapes, kayak launch pier and permanent kayak clubhouse. More game nodes with more information mark the water surface of the whole bay extending the range to explore Snug Harbor Cultural Center and Botanical Garden, Fresh Kills Park, Newark’s Riverfront and connecting to the New York water trail.

This strategy of temporary installation, underutilized site mini-alterations, site re-use and hybridization is not an unusual urban tactic. What is unusual is that it is part of a real-estate development project.

Often these tactics are deployed by street artists, art and design festivals sponsored by urban or environmental advocacy groups such as community groups, NGOs or quasi-public agencies. The reason that the client supported the development of these tactics was that they would bring attention to the project, generating revenue and create an amenity for the new residents. In order to succeed they would require several key negotiations that Celadon, as a new major urban actor in the bay, would broker. For example, the Jersey Gardens mall and Port Newark security patrol is tolerant of a program that engages their parking lot and forest as a game surface as long as it doesn’t trigger a homeland security alert. The construction of a traffic light and pedestrian crossing on the road to IKEA is important because many trucks traveling at high speed and carrying stacked shipping containers frequent this road. Finally, buoys in the water are needed to demarcate shipping lanes, ferry zone and safe kayak crossings.

![P:[ TILL ]�2-TILL RESEARCHPublicationsPaiseaDosCeladonExis](https://www.thenatureofcities.com/TNOC/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Celadon_Phase12-522x420.jpg)

![P:[ TILL ]�1-TILL PROJECTS�1 CURRENTTERN GROUPD0602 CELAD](https://www.thenatureofcities.com/TNOC/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Site_Plan2-630x409.jpg)

We perceive our urban environment in a distracted way. We rarely focus our attention out in most situations. Even in a rarified environment such as the theater, museum or art gallery we wander distractedly, attaching given images to mental images and memories.

What we do have, however, is habits, and we often repeat our thoughts, gestures and movements over time, accumulating a deeper understanding of some places more than others.

Three phases of urban interventions in the Celadon project located within the site boundary, around the site boundary, in the sites around the bay and in Newark Bay were created in order to encourage people to further explore a place they have been before even if it was just a glimpse from a car window or a tired gaze from an airplane.

In other words, this project is not designed to be an inward looking otherworld, a place of escape, or a gated community.

Finance design

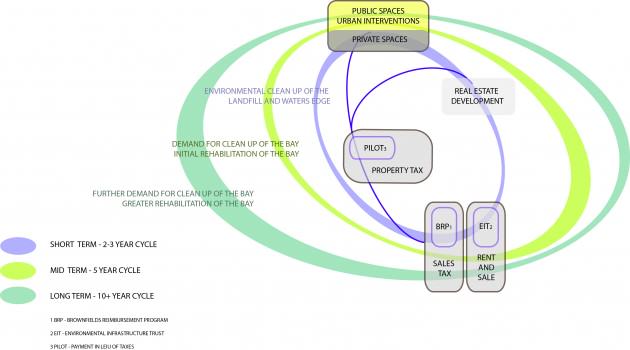

Often, there is a paradoxical situation in accessing the funds to build a real estate project: in order to service the debt portion of the capital stack, taxes and cash-flow are needed – but they cannot be generated without the buildings being built. The financial strategy must therefore reach far forward while operating in the present simultaneously and concurrently otherwise the model falls apart.

This section describes three concurrent cycles – short, medium and long – that are launched through clusters of different financial strategies to allow this environmentally activist real-estate development to happen. Essentially the three subsidies described below allow a clean up of the landfill, new leachate system, landfill cap, construction of private and public spaces including the ferry terminal, and the Celdaon real-estate project itself. These spaces, structures, and the programs attached to them allow three concurrent cycles to occur.

At Celadon the financial means are provided by incremental property taxes, sales taxes and rents. An example of this is Tax Increment Financing (TIF): the anticipated new and additional taxes (hence tax increment) that will be generated by the properties yet to be built are sold to investors in order to raise upfront money for the project.

Brownfields Reimbursement Program (BRP) and the Payment In-Lieu of Taxes (PILOT) can be structured as TIF’s. The BRP permits the reimbursement of 75% of the sales taxes (plus a few other state taxes) generated on the site for 75% of the remediation costs. The BRP is a New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) program that is implemented by the New Jersey Economic Development Authority (NJEDA). Under the PILOT, the property tax burden (consisting of municipal, county, and school tax) is reduced by eliminating the school tax and substantially reducing the county tax. The difference between the market rate tax payment and the PILOT payment can be montetized through issuance of bonds. The PILOT can be for a period up to 30 years (reduced after 15 years) from the completion of the project.

Although not a TIF, the New Jersey Environmental Infrastructure Trust Financing Program (EIT) also depends on the cash flow that is expected to be produced from the real-estate project. The EIT is largely funded by the EPA’s Clean Water State Revolving Fund, which provides money for the state agency. The EIT program is run in conjunction with the NJDEP, which provides 75% of the funds at 0% interest. The remaining 25% is provided through a bond issuance by the EIT and is currently priced at approximately 2% interest. That is a 20-year loan at an average interest rate of 0.5%! The BRP and EIT can be used for environmental cleanup and environmental infrastructure, without which it would be more difficult, if not impossible, to make economic sense for a landfill-based real-estate project. The proceeds of the bonds issued under the PILOT program can be used in the real-estate project itself.

For simplicity’s sake this description does not talk about the property being in an Urban Enterprise Zone with its own subsidies and the availability of New Markets Tax Credits, which can be sold as quasi equity.

Celadon was paused in 2008 due to local, state and federal issues and the 2007–2012 global financial crisis; therefore the description below of the three cycles is offered as an example of this innovative and sophisticated environmental activist finance design.

It was a great idea but was undermined by economic and political forces beyond our control.

The short-term cycle for Celadon was proposed to start with the above-mentioned financings, which lead to environmental remediation of the leachate system and upgrading of the landfill cap; thus creating the usable spaces of the real-estate development. Private spaces such as residential units become part of the saleable and rentable real-estate and they generate sales proceeds, rent and sales taxes, thus servicing the EIT, BRP and PILOT financings. The minimum time frame to build the first phase of the Celadon was approximately two years. After this each phase takes between two to three years. Therefore this short-term cycle ranges from two to three years and with five phases in total it is completed in 10 years.

Once again, the medium-term cycle starts with the financing program, leading to the construction of the waterfront public spaces – including the promenade, the pier, the ferry terminal and the ferry itself – which bring people to, onto and into the water, thus creating a first connection with the bay. The increased likeability of the experience near and on the water enhances the desirability of the real-estate. That in turn leads to higher sales taxes, higher rents and better sales proceeds. Consequently, there is more money to support environmental stewarship of the bay and urban interventions around and in the bay. The time it takes to build, and get the kinks out of the programming to generate the flow of people is at least five years. If done successfully, the traffic flow keeps on increasing over a long period of time.

The long-term cycle is about creating an identity, particularly with a sound signature for Newark Bay. A lot of people think of Asbury Park when they hear Bruce Springsteen and vice-versa. Expanding on this we proposed to support new and exsiting musicians, poets, storytellers and sound artists around Newark Bay, and to call it NewB music. The cities around Newark Bay – Newark, Elizabeth, Iselin – have living arts that include Brazilian, Indian, and their local fusion. The sound signature would be achieved through installations, live performances, and mass marketing. The time frame to connect this could easily take 10 years; the idea is that a highly diverse group of sound projects as well as a greater desirability of living along the Bay of NewB would generate additional resources for Newark Bay.

Movement systems

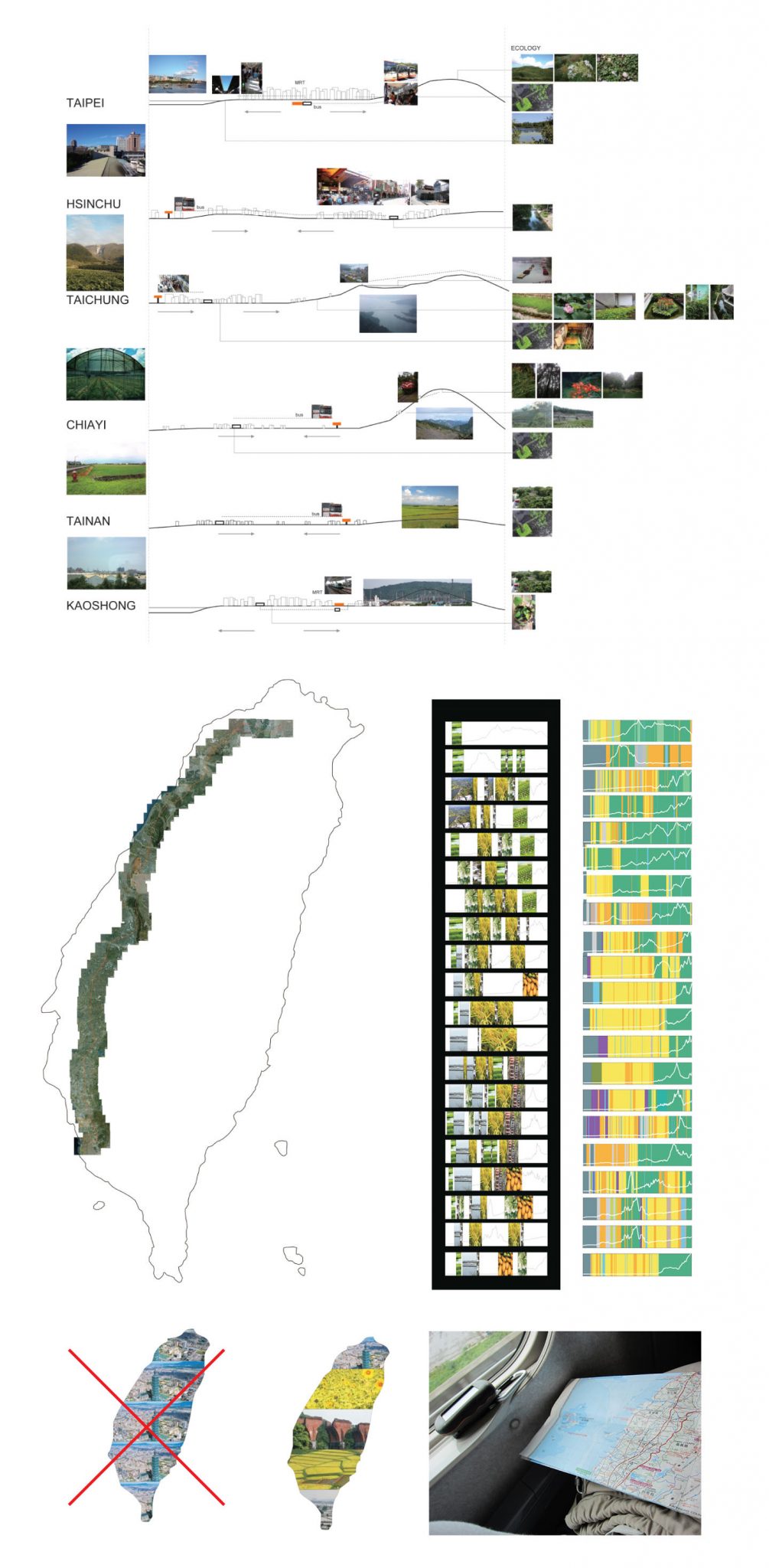

Brian McGrath (also a TNOC writer) offers the concept of correlative space, which is a space, created by movement systems that bring together different groups, urban elements and ideas about the city (McGrath). For example, in New York the subway system and suburban commuter train lines allowed for the concentration of new business districts in both Lower and Midtown Manhattan, while the new Skytrain in Bangkok has created a multi-level urban armature which interconnects formerly distinct urban shopping enclaves.

A recent workshop called High Speed Urbanism hybridized correlative space with environmental activism. Students studied the high-speed train that connects many cities in Taiwan forming one megalopolis. One project titled Pulsating Taiwan imagined the train as a sensing device scanning the island and logging urban ecosystem cycles into the rhythm of the morning and evening commute, correlating the patchy dynamics of spectacular cyclones, landslides, earthquakes and urban regeneration with micro-measures of local biodiversity and food production into sustainable growth.

Similar movement systems with environmental activism already exist in Newark Bay on a smaller scale but are not yet correlated together, below are three examples.

New Jersey PATH trains run parallel to the Passaic River between Journal Square and Harrison Stations passing directly opposite the clean up project of the Diamond Alkali site, the source of dioxin, the major contaminant of the Newark Bay water body. Starting in July 2011 a weekly PDF report provided updates on the project. In addition commuters on the train could witness these changes like a stop motion film or flipbook. Each day it is possible witness change, for example the construction of a new sheet pile wall, then excavators removing the soil, new hoppers and barges, a floating pipeline, then tugboats delivering clean back fill, more cranes, etc.

Another example is Captain Bill of the Hackensack River Keeper taking a group on one of over 35 of summer eco-cruises and guided canoe paddles. In addition to introducing the environmental history of the bay, with his binoculars, he is constantly monitoring the bay from the water, keeping track of the health of the salt marshes, bird watching, crab spotting as well as double checking on encroachment and the activity of storm sewer outfalls. The newsletter Hackensack Tidelines, in addition to providing updates on legal proceedings is an almanac of wildlife observations. Learning from the Hudson River Almanac, this simple media formalizes everyday ecosystem process observations into a public database

In 2006 the Newark Bay was scanned using sonar imagery in order to evaluate the age of industrial-age deposit, the images of this project offer a compelling insight into the links between new media and new spatial practices of the bay. Seeing underwater is something only for crystal clear water and what is revealed in the scan are the canyons dredged from the bay for shipping. These effectively keep the large tankers in a tight watery lane, opening the remainder of the bay, which is mostly made up of shallows, as a safe and spectacular surface for kayak exploration. Handheld depth finders and fish finders allow kayakers to continue this ‘reading’ of the bay at an intimate scale.

Celadon as a model

Celadon is a development model which emerged in the vast, dispersed, networked environment for housing, work, leisure and consumption that top-down management systems legislated by master planning, land use and zoning could no longer keep up with. It anticipated, and is now confronting the collapse of our carbon-based urban model. Newark Bay will continue to grow by its own measures. How can we engage and not negate or override this type of ad-hoc change? Expanding from the practices developed for Celadon, and others observed and noted above, we propose enhanced environmental activism that resonates with New B sound. Soon, we hope that more formerly contaminated real estate developments will also contribute to creating a newly famous Newark Bay. In other words these deeply sectional and multiple crisscrossing and parallel, slow speed and high-speed movements together form a correlative space that transforms the bay.

Feedback loops only work when there are linkages among scales. Finance strategies only work when they are concurrent. Urban designers are trained to create spatial strategies, physical environments and programs that allow these loops and cycles to correlate and make a difference. How can the design of urban ecology research account for this and participate? We are in an extremely creative time of rapidly diversifying tools with which to re-imagine and re-define the 21st century city. The Celadon urban design model allows us to now imagine integrated cultural, social and ecological identities in many newly famous waters around New York City, such as Hudson River Upper Bay, Jamaica Bay, Sandy Hook Bay, Raritan Bay, Flushing Bay – learning from other famous movement systems and famous waters around the world – directing future development into more sustainable growth.

Victoria Marshall

Newark, NJ USA

Acknowledgement

TILL team: Dil Hoda, Brian McGrath. Mateo Pinto, Kate Cella, Flora Chen, Marc Brossa, Phanat Xanamane and Manolo Ufer.

3 Comments

Join our conversation