This essay is part four in a series. Since 13 March 2020, our team of social science researchers has been keeping a collective journal of our experiences of our New York City neighborhoods, public green spaces, and environmental stewardship during COVID-19. Read the essays from spring, summer, and fall here.

I. Marking time, mourning, and spring rebirth

After hitting the one year mark of the official declaration of the pandemic, we found ourselves both looking ahead with hopeful signs of spring, vaccine distribution, and possibilities for greater openness in our social worlds—while also reflecting backward on just how much has been lost. The first large-scale public memorials occurred this winter, including a national memorial on 19 January held at the Reflecting Pool on the National Mall in Washington, DC as well as the 15 March NYC memorial held at the Brooklyn Bridge in New York City.

These reflections came through in our personal journals alongside wider conversations that occurred in the media:

Excerpt from Lindsay’s journal on 12 March 2021:

It was an unseasonably warm day—got as high as 69 degrees, so Mia and I went down to Valentino Pier. The neighborhood is coming back to life with kids and dogs everywhere. We saw a group of brave, excited teenagers jumping off the pier into the icy cold water. Their exuberance and pent up energy was palpable! I ran into neighborhood mom friends I haven’t seen in months and am even making a new friend. We spontaneously decided to eat outside at the taco place and Mia was thrilled. We all need a change of pace, to be in public, to see strangers again.

Excerpt from Michelle’s journal on 16 March 2021

This morning I heard a robin singing for the first time when I stepped into the backyard right at dawn. I was immediately thrown back to memories of last spring—lying awake listening to ambulance sirens mingling with robins singing. The past week, the weather has been up and down, teasing us with a promise of an awakening world. I feel like we are in the home stretch, and it is making me more impatient than at any time during the last year—knowing it will be safe to be amidst the world again, and yet not quite there.

Partnerships for Parks, a citywide organization that supports neighborhood stewardship groups, distributed over 50,000 purple crocus bulbs to more than 100 community groups in the fall of 2020 as a memorial to COVID-19 victims. This practice of planting flowers and trees as living memorials is not new, but is a patterned human response, as we engage with and care for nature to mark important events, lives lost, and cycles of birth and death. For example, following September 11, 2001, Congress authorized the USDA Forest Service to create the Living Memorials Project to harness the healing power of trees and support communities in their efforts to remember, respond, and reflect on that tragic event. As researchers, we documented hundreds of these memorials and interviewed community stewards both at the crash sites and in cities and towns across the country. We found that those that create and care for these living memorials are drawn to nature as a catalyst for recovery, caring for both people and place. In this way, these environmental stewards serve as “green responders” who help reknit lives and landscapes and enable recovery from different types of disturbance.

II. Vaccines, economic recovery, and mutual aid

Our team members and our family members began to receive vaccines. New guidance was offered by the CDC that allowed vaccinated people to gather in small groups, and public statements by elected officials gave us hope that summer might even allow for travel and family gatherings.

Excerpt from Michelle’s journal on 25 February 2021

Last night I went to CitiField stadium after work for a vaccine. The energy in line was not an energy of frustration, of waiting—not like at the subway or the bus or Penn Station when you just want to get on that train home. It was an energy of hope—of good times being ahead, together. I waited 4 hours, but I was happy to have gotten my shot with other Queens residents (oh, the translators!!).

While vaccines signal a future recovery and reopening, we are aware that many remain in acute need of ongoing support. On 10 March the $1.9 trillion COVID recovery bill passed Congress and was signed into law by President Biden as the American Rescue Plan on 11 March. In addition, alongside and independent of this federal funding, there exists a network of bottom-up, local organizations working to provide direct support to residents. Community organizations and stewardship groups have continued to adapt their programs to meet local needs like food insecurity, such as Brooklyn Grange offering sliding scale Community Supported Agriculture food boxes. At the beginning of the pandemic, mutual aid groups popped up all over the country—with most concentrated in cities—primarily to help community members get groceries, medicine, and other short-term supplies. A year later, many of these groups have evolved to fill ongoing needs by maintaining community fridges, providing mental health care, and even working to expand internet access. These emergent groups are now facing the challenge of how to sustain their efforts as many volunteers return to full time work and major donations slow. Some of our team members have continued to be involved in these mutual aid efforts as a way of being a part of neighbors-helping-neighbors.

Excerpt from Laura’s journal 30 January 2021

It has been inspiring to know that my local mutual aid group is still serving the community by delivering groceries to neighbors in need free of cost. In addition, they have started offering financial assistance of up to $100 per week on an as-needed basis. Most of this money comes from individual donors. I’m not one of the most consistent volunteers, but I agreed to take on 3 dispatch calls a week in the winter. I spoke with one woman who needed help to pay her monthly bills and we were able to send her funds through venmo within about an hour. She called me back to say how thankful she was and also to ask how frequently she is allowed to call the hotline to ask for more money. It was a reminder that despite the sustained effort of Crown Heights Mutual Aid—which has continued for almost an entire year so far—our neighbors are still desperate for more support.

Excerpt from Michelle’s journal 17 March 2021

I have also been thinking about social connections during the pandemic. I ran across this paper a couple of weeks ago, which shows the effects of reduced social connection during the 1918 Spanish flu on social trust for decades to follow. In talking with Kate Peterson of Proud Astorian, I mentioned this outcome from the 1918 pandemic and she noted that it is the opposite now, she felt more connected than before. And I wondered to her whether it is because she has formed this group that meets in person during the pandemic—and whether people in civic groups are having a different experience than people who aren’t part of groups. I went to Socrates Sculpture Park on Sunday, when the Astoria Mutual Aid Network had their picnic—open to all volunteers—and the park was filled with maybe 75-100 people on socially distanced picnic blankets, with booths/tables for Astoria Fridges, Astoria Food Pantry, and other groups that all have formed during the pandemic—and there was live music and a stage and people generally chatting with each other. All of that is a result of people coming together during the pandemic. And they are younger—most people somewhere in their 20s-40s. Are people at higher risk of COVID experiencing the same community? What is it like for essential workers, for the elderly? If they reached out to mutual aid groups, they might also feel this sense of connection, but others might still feel isolated.

III. Digital communities, social worlds, and stewardship practices

In our everyday lives, we remain attuned to our hyper-local surroundings and seasonal rhythms—the first crocuses appearing, the changing of holiday decorations on front doors, the shedding of the heaviest winter jackets—while also connected through the digital world to distant communities of like-minded people. This juxtaposition of staying within the same four walls or the same few blocks, while connecting to people across time zones and geographies through Zoom squares has been both energizing, but also disorienting. The possibilities for meaningful, digitally-enable interaction are greater than ever. How do we now take back these connections fostered at a distance to transform our lived experience of place?

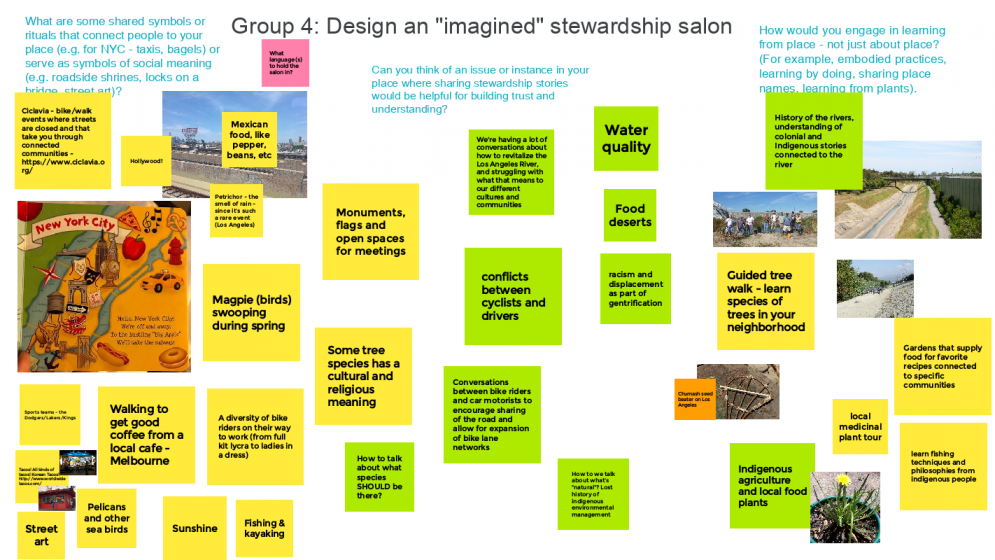

For example, our research team participated in The Nature of Cities Festival on 22-26 February and organized a “virtual stewardship salon” (along with Heather McMillen and Marisa Prefer) as an interactive seed session with a goal of strengthening participants’ sense of reciprocity with nature. While we had been organizing these salons to facilitate conversation, co-learning, and exchange among urban environmental stewardship practitioners, researchers, and artists on an ongoing basis for two years (see McMillen et al. 2020), we had put them completely on hold during the pandemic. This was our first effort to re-constitute this dialogue in a virtual setting. We organized an Indigenous land acknowledgement across our locations, a set of brief presentations and ground rules, and facilitated breakout groups where we shared our own stewardship stories and collectively designed imagined stewardship salons with participants from around the globe.

While the festival overall buzzed with creative energy and inspired with ideas across disciplines, geographies, and time zones—and our team members attended plenary sessions from 2am until 7pm EST—we also found ourselves craving in-person exchange. Virtual platforms can lower barriers to enter into conversations and the cost of travel or size of a lecture hall no longer needs a limit who can attend our meetings. But as we seek to learn not only from each other, but from place, we are reminded of the importance of embodied action—of being there, in nature, in community, in the company of strangers—of the need to smell, taste, feel, and do.

Similarly, NYC Open Data Week ran from 6-14 March; this year completely virtual, the reach of the presentations extended beyond the boundaries of NYC, connecting open data efforts with those in other parts of the US and Europe. One event focused on a hackathon for litter cleanup groups, as organizers look for a more sustainable model for their efforts. A central question driving this effort was: who takes care of the streets? For a weekend, litter group organizers and coders/UX/designers hung out on the online platform Discord, talking about how to clean up trash in NYC’s streets. Hearing these groups explain their origin stories, goals, and efforts aligned with other stewardship groups we have surveyed and interviewed in the past. A big difference for the newcomers, operating in a virtual world aimed at supporting embodied practices, was how recruitment and participation occurred. Instagram is where a lot of the organizing is happening—with Instagram handles serving as centralized directories and highlighting emerging coalitions that stretch citywide.

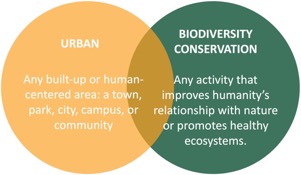

Both of these experiences surfaced more questions for our team. How can we braid the best of both approaches—digitally enabled connections with distant others grounded in our close, direct contacts and experiences? Might COVID-19 be pushing us closer to being able to shape and realize biocultural stewardship practices that are both planetary and local, urban and rural, virtual and physical? What would these cultures of care look like?

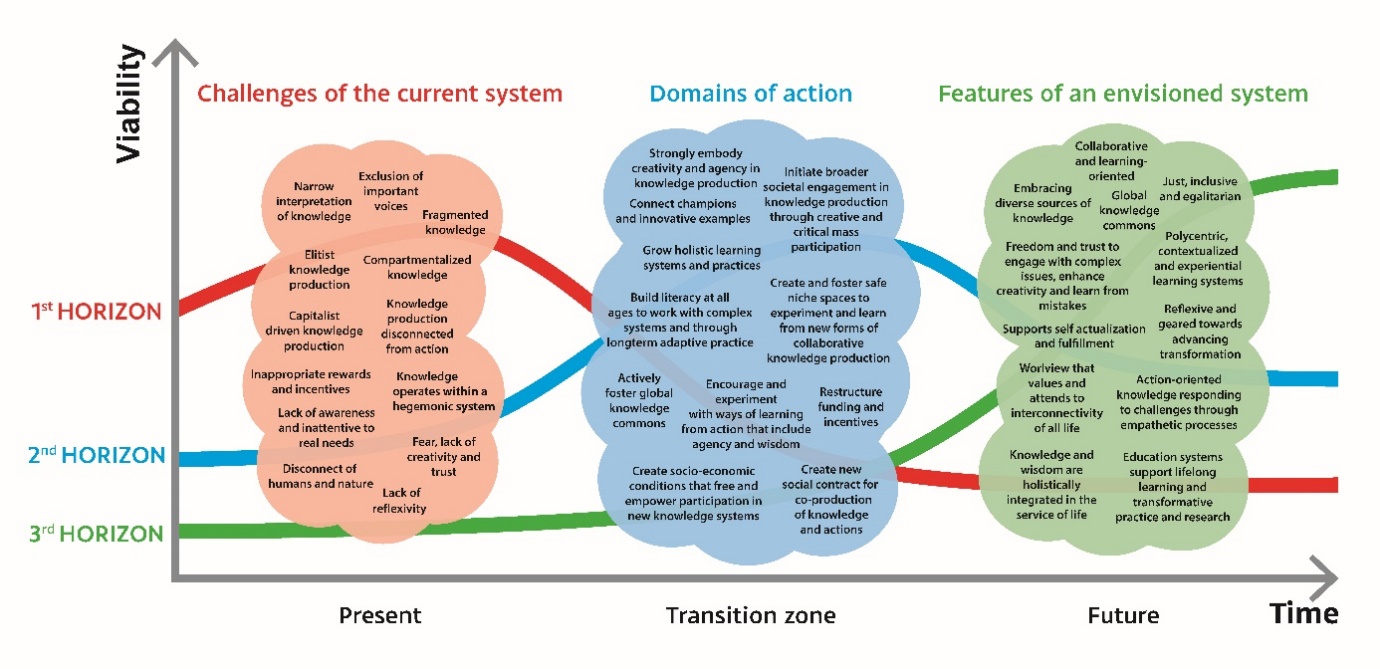

IV. Learning from crisis—what will endure?

In addition to our personal observations and reflections, we began to analyze the results from our summer interviews with civic stewardship groups and public land managers about how they were adapting and responding to COVID-19. As researchers, we were interested in the ways groups learned from past crises, and how this learning enabled them to respond to COVID-19. We asked stewards to reflect on their experiences following Superstorm Sandy in 2012, as well as their ongoing learning and response to racial injustice, particularly the context of the BLM protests following the murder of George Floyd in the summer of 2020. While these crises all have vastly different contexts and impacts, many groups drew parallels between them. Some described how the networks they built after Sandy were re-engaged to respond to food insecurity from COVID-19. Others explained how ongoing racial justice initiatives, including DEI trainings for their staff and board, enabled them to think critically about how communities of color were disproportionately impacted by COVID, and led to some creative programming to share resources with poorly served neighboring parks.

In our first essay, we posted a series of questions: how does the pandemic change our relationship with the city, nature, and public lands? How might we transform the public realm to better adapt to our new reality, in ways that are equitable, safe, supportive, and welcoming for all? How can our relationship with nature help us restore and strengthen our relations with each other at all scales: individual, group, and societal? Some of the answers to these questions are beginning to be unearthed as we move towards the light at the end of the tunnel, with the knowledge that there will be hard times ahead. The pandemic has strengthened many New Yorker’s relationships with public space as residents spilled out into parks and onto the streets, establishing new personal rituals and habits with their local environment in an effort to escape the confines of their apartments.

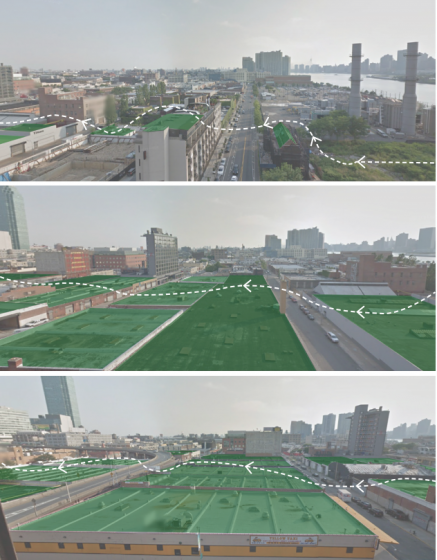

While pouring over our interview transcripts from the past summer, it is fascinating to reflect on how drastically use of public lands shifted at height of the pandemic and consider which of these changes will persist. One of the most common reflections by land managers was the feeling of being both overwhelmed and overjoyed by an explosion in visitation to public parks and forests. These sentiments have incited a number of questions for the coming spring and summer season: will this surge in visitation persist? Will patterns of use shift from hyper-local nature to more distant locales? As more people are vaccinated and case numbers fall, will trips to local parks and woodlands be replaced (for some) by vacations to exotic locations or family visits, or have these local parks become some people’s new routine? More urbanites are dispersed or staying in the suburbs and while many workers may return to in-person office work over the summer, there will likely be a “tectonic shift in how and where people work” with many continuing to work from home. Will this change in work and commuting shift the demographics of our city, and how will this impact the public spaces that we share and care for? How do we plan for and equitably serve all residents—including those who cannot travel to distant locales and for whom nearby greenspace is the only nature experience available?

Another prominent theme in these interviews is the burden of maintenance that became a huge focus with this new parks visitation. We’ve already seen numerous adaptations at all scales in response to this increased need for maintenance—ranging from the grassroots, community-organized clean-ups, to advocacy to increase municipal parks budgets, to federal relief and employment programs. For example, in New York City, federal recovery money is being used to hire hundreds of parks maintenance workers for a one-year term . These temporary job programs will help get New Yorkers back to work and provide much-needed maintenance for New York City Parks. The New Deal of the 1930s resulted in an immense investment in New York City parks and playgrounds that lives on today. Will more investment in green space lead to a more permanent transformation of the public realm? The COVID-19 pandemic has shined a brighter light on the way in which parks and open space are critical infrastructures that support public health and well-being; will we emerge from this crisis with broader public support for and engagement with green spaces?

* * *

Overall, we found that all stewards—civic and public—responded to the novel conditions of the pandemic. Some adapted more nimbly than others, but the question remains: whose practices will most fundamentally be transformed and how in order to help enable more resilient and inclusive cities and greenspaces?

We are not yet in the recovery phase from this global pandemic, so time will tell in what ways we can transform our society or return to historical patterns, but holding onto deep memories and trauma that continue to influence us on an individual and societal level.

After a year of journaling, interviewing, and reflecting—the story continues to unfold.

Lindsay Campbell, Michelle Johnson, Sophie Plitt, Laura Landau, Erika Svendsen

New York

about the writer

Michelle Johnson

Michelle Johnson is a research ecologist with the USDA Forest Service at the NYC Urban Field Station.

about the writer

Sophie Plitt

Sophie Plitt is National Partnership Manager the the Natural Areas Conservancy. Sophie works to engage national partners in a workshop to improve the management of urban forested natural areas.

about the writer

Laura Landau

Laura is currently pursuing a PhD in geography at Rutgers University. Her research focuses on the civic groups that care for the local environment, and on the potential for urban environmental stewardship to strengthen communities and make them more resilient to disaster and disturbance.

about the writer

Erika Svendsen

Dr. Erika Svendsen is a social scientist with the U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station and is based in New York City. Erika studies environmental stewardship and issues related to hybrid governance, collective resilience and human well-being.

18 Comments

Join our conversation